SPOTIFY PLAYLIST: September 2025 (Art & Theology): A new monthly playlist featuring a range of faith-based songs, including “Day by Day” by Lowana Wallace and Isaac Wardell of the Porter’s Gate (especially apt for Labor Day!), sung below by Kimberly Williams; “Jesus of Nazareth” by the early twentieth-century hymn writer Hugh W. Dougall, performed in a bluegrass style by the Lower Lights; and a fantastic instrumental jazz arrangement by Alice Grace of the classic children’s song “Jesus Loves Me,” performed by the Indonesian group Bestindo Music (Grace is at the keys).

+++

VIDEO: “The Apostles’ Creed”: This video presentation of the Apostles’ Creed, one of the oldest statements of Christian belief, used across denominations, was created in 2016 by Faith Church in Dyer, Indiana, using twenty-one of its members to voice the lines. [HT: Global Christian Worship]

+++

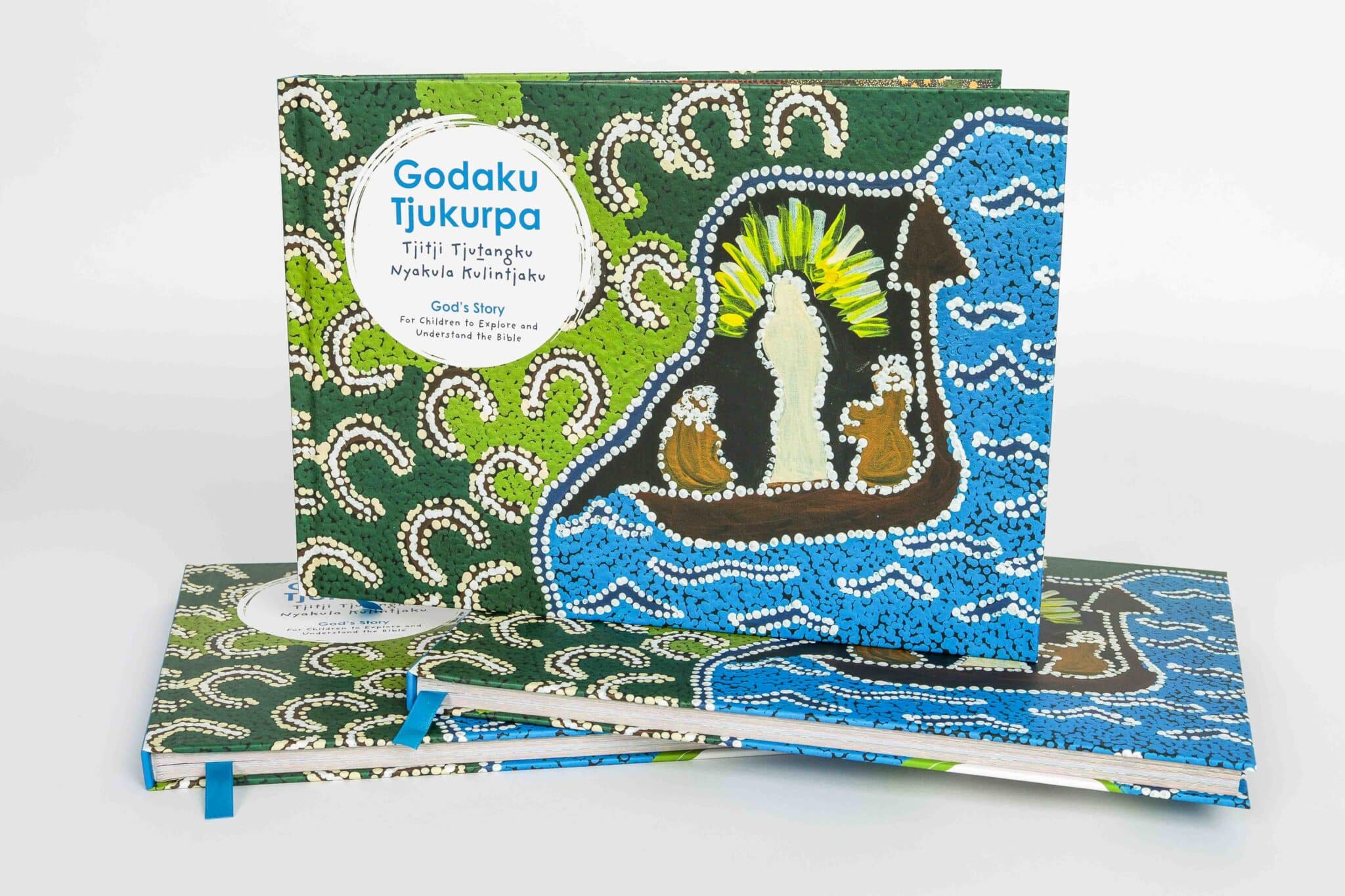

CHILDREN’S PICTURE BIBLE: Godaku Tjukurpa (God’s Story): Nami Kulyuru, a long-serving Pitjantjatjara Bible translator and artist from Central Australia, had the vision to pass on the stories of the Bible to her grandchildren and other young Pitjantjatjara readers using traditional Anangu paintings, compiled in book format. She began the artistic work in 2021 but shortly after was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. Following her death in 2022, her friends and colleagues rallied together to complete the project, which was published last November by Bible Society Australia. [HT: Global Christian Worship]

Spanning the Old and New Testaments, Godaku Tjukurpa (God’s Story) features fifty-four Bible illustrations by Pitjantjatjara artists, along with descriptions in Pitjantjatjara and English. It is available for purchase through the Koorong website, but it appears that it can ship only to Australia or New Zealand.

+++

SHORT FILM: Feeling Through, dir. Doug Roland (2019): Nominated for an Academy Award in 2021, this eighteen-minute film is about a homeless teen (played by Steven Prescod) who encounters a DeafBlind man (played by Robert Tarango) on the streets of New York City. It was inspired by an actual experience writer-director Doug Roland had some years earlier. He partnered with the Helen Keller National Center to make the film, including casting a DeafBlind actor as co-lead, the first film to ever do so. You can watch Feeling Through for free on the film’s website, along with a “making of” documentary. Here’s a trailer:

+++

FEATURE FILM: Places in the Heart, dir. Robert Benton (1984): Set in Jim Crow Texas during the Great Depression, this film centers on the recently widowed Edna Spalding (Sally Field), a middle-age white woman who is struggling to run the cotton farm she inherited from her late husband and to make ends meet for herself and her two small children. To earn some cash, she takes in a boarder, Mr. Will (John Malkovich), a bitter World War I vet who is blind, and she hires Moze (Danny Glover), a Black drifter who is being harassed by the Ku Klux Klan, to teach her how to plant and harvest cotton. The three are thrown together out of necessity and help each other survive.

It’s a pretty good movie overall—and it won Sally Field her second Oscar for Best Actress—but what leads me to recommend it is its theologically profound closing scene, which shows the ordinance of Communion being celebrated at the local country church. First Corinthians 13:1–8, the famous “love” passage, is read from the pulpit, and the choir launches into “In the Garden” (a hymn inspired by the risen Christ’s appearance to Mary Magdalene on Easter morning) as the plates of bread and grape juice are passed down the pews. The camera zooms in close on each congregant as they receive the elements, starting with a couple whose marriage had suffered due to infidelity but who, in this scene, silently reconcile.

On my first watch, what signaled to me that we had entered the realm of the imaginary (the mystical? the aspirational?) was the presence of Moze, who had left town the previous night after having been beaten by Klansmen; he’s here, with no visible wounds, in this conservative white church in the 1930s that very likely would not have welcomed him, being served the body and blood of Christ by a deacon. I believe that some of the white men in the pews in front of him are repentant Klansmen who, when Mr. Will identified them under their hoods by their voices the previous night, mid-assault, slinked away in shame. Within the row, too, is the mortgage collector who was in conflict with Edna, insisting that she sell the farm.

After Edna receives the elements, she passes them to her husband, Royce, who was dead before but here is very much alive. He then passes the elements to the young Black teen, Wylie, who had shot and killed him in a drunken accident, whom vigilantes then lynched. “Peace of God,” they say to each other—a traditional Christian greeting expressing love and reconciliation. The final frame lingers on Royce and Wylie, sharing the meal together, and I’m intrigued by the actors’ choices of expression: Wylie is serene, grace-filled, whereas Royce appears befuddled, perhaps recognizing for the first time the blessed tie that binds him to his Black neighbor, his brother in Christ.

This scene speaks powerfully of the invitation of the Lord’s Table—open to all, even the most morally odious, who would come in humble confession of (and turning from) sin and reliance on God’s mercy through Christ, which heals and transforms. Partaking of the meal are various people from the community—people who have cheated on their spouses; people with ornery dispositions; people with narrow economic interests, who fail in compassion; people who have stolen; people who have committed cruel, racist, violent acts; people driven to drink, leading to fatal harm; people who have silently allowed racial terror to reign in their town. All these sinful, forgiven people make up the body of Christ, are united under his cross. They’ve often hurt one another, but the Holy Spirit is at work making them a new creation. I see this final scene as a picture of heaven, where wrongs are redressed, and of the “beloved community” Martin Luther King Jr. talked about.

Places in the Heart is streaming for free on Tubi (no account required).