The Old Testament reading in the Revised Common Lectionary for this coming Sunday, Trinity Sunday, is Isaiah 6:1–8:

In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, high and lofty, and the hem of his robe filled the temple. Seraphs were in attendance above him; each had six wings: with two they covered their faces, and with two they covered their feet, and with two they flew. And one called to another and said,

Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts;

the whole earth is full of his glory.The pivots on the thresholds shook at the voices of those who called, and the house filled with smoke. And I said, “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips, yet my eyes have seen the King, the LORD of hosts!”

Then one of the seraphs flew to me, holding a live coal that had been taken from the altar with a pair of tongs. The seraph touched my mouth with it and said, “Now that this has touched your lips, your guilt has departed and your sin is blotted out.” Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” And I said, “Here am I; send me!”

Wow. What a truly awesome passage!

I’d like to share two songs inspired by it as well as two visual artworks. The first song is a choral work by the English composer and organist Sir John Stainer (1840–1901), titled “I Saw the Lord.” It was performed by The Sixteen under the direction of Harry Christophers and appears on the ensemble’s 2009 album A New Heaven.

The first stanza is the King James Version of Isaiah 6:1–4, and the second stanza is the third verse of “Ave, colenda Trinitas,” an anonymous Latin hymn of the eleventh century, translated by John David Chambers (1803–1893).

I saw the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up,

and his train filled the temple.

Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings;

with twain he covered his face,

and with twain he covered his feet,

and with twain he did fly.

And one cried unto another,

Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts:

the whole earth is full of his glory.

And the posts of the door moved at the voice of him that cried,

and the house was filled with smoke.O Trinity! O Unity!

Be present as we worship thee,

And with the songs that angels sing

Unite the hymns of praise we bring.

Amen.

Christian biblical commentators have discerned in Isaiah 6 two Trinitarian references: the three “holys” pronounced by the angels (v. 3), and the use of both a singular and plural pronoun in God’s question in verse 8: “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” (emphasis mine; cf. Gen. 1:26). Unity in plurality. Further, the New Testament relates this passage to both Jesus (John 12:41) and the Holy Spirit (Acts 28:25). That’s why it’s commonly read on Trinity Sunday, and why Stainer has appended to it a Trinitarian hymn text.

Of Stainer’s musical setting, William McVicker writes,

It is often said that I saw the Lord was written with the acoustics of St Paul’s [Cathedral in London] in mind. It is scored for double choir with an independent organ part. The music’s drama is achieved by the simple, largely homophonic texture, and the interplay of the two chorus parts with that of the organ. Stainer breaks into an imitative texture at the words ‘and the house was filled with smoke’ and again in the final verse section, which is reminiscent of a Victorian part-song.

The music is grandiose, majestic, as one would expect for the encounter it frames, which involves robes, thrones, angelic attendants, shaking doorposts, smoke, and an all-pervasive divine glory.

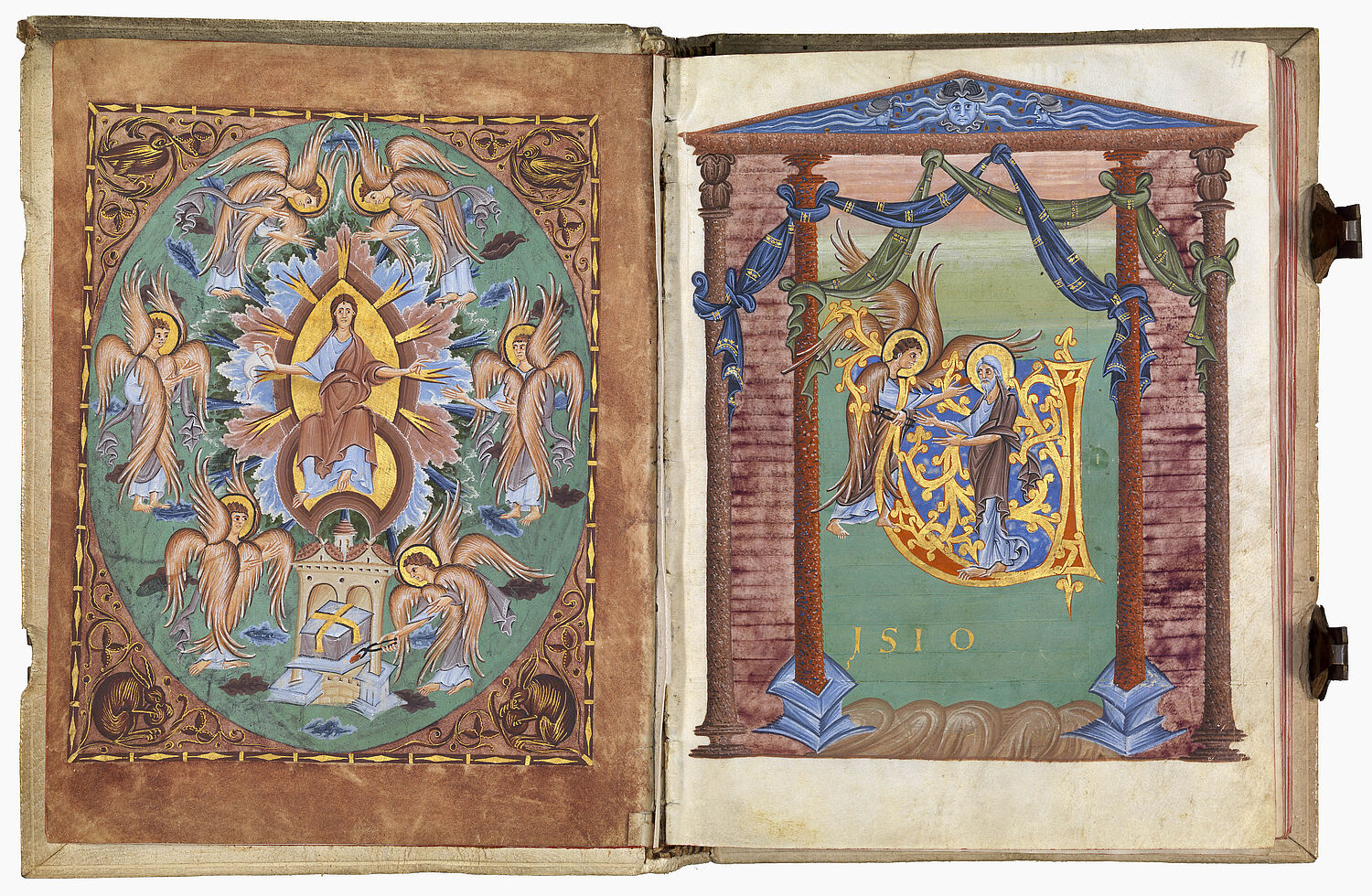

I suggest listening to Stainer’s choral piece as you look on the following page spread from a high medieval German manuscript produced in Reichenau. The manuscript is a copy of Jerome’s (Latin) commentary on Isaiah, with glosses added in the Alemannic dialect of Old High German, and these are the only two images inside.

The island monastery of Reichenau on Lake Constance in southern Germany was an important center of illuminated manuscript production in the Ottonian period (919–1024) of the Holy Roman Empire. The miniatures painted there are among the finest of the Middle Ages. (For another example, see the one I shared back in 2020.)

On folio 10v of the Isaias glossatus that’s kept at the Bamberg State Library, God in the form of Christ sits in a mandorla from which trifold bursts of light shine forth, backed by mauve and powder-blue billows of smoke. In his right hand he holds a scroll that represents the word he speaks to Isaiah in 6:9–13, and the words he will continue to supply him with throughout his ministry. Hovering above a smaller-scale temple, God is attended by six seraphim (lit. “burning ones”), one of whom removes a hot coal from the altar with tongs. All this takes place within a green oval, which is surrounded by a brown and gold decorative border of vine tendrils housing two birds and two hares.

On the opposite page, folio 11r, the tong-bearing seraph touches the coal to Isaiah’s lips, purging his speech and thus fitting him for the office of prophet. This cleansing act is in response to Isaiah’s humble confession of sin, having beheld God’s holiness: “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips . . .” (v. 5). The artist shows Isaiah’s hands open and arms outstretched, welcoming God’s cleansing and accepting the call to service: “Here am I; send me!” (v. 8). Notice that this exchange takes place within the letter V, from the opening of Isaiah, “Visio Esaiae” (The vision of Isaiah . . .). The miniature is a historiated initial—that is, an enlarged letter at the beginning of a paragraph that contains a picture.

Now let’s shift gears to two Isaiah 6–based works that were made in a folksier idiom. Take in this pen, ink, and watercolor image by the award-winning Austrian illustrator Lisbeth Zwerger, from her book Stories from the Bible (North-South Books, 2002), originally published in German as Die Bibel in 2000:

This book contains some of the most imaginative biblical artworks of the past century (I shared a sampling on Instagram), and I recommend it for all Christian bookshelves!

In contrast to the frontal wide shot given by the anonymous Reichenau artist, in Isaiah’s Calling Zwerger zooms in on just one detail of the scene, structured along a diagonal. Isaiah stands at the bottom right in the dark, dwarfed by the immense train of God’s robe, which is pure light. It contains letters that I can’t make out into words; can you? I would have assumed they spell out the passage from Isaiah 6 (in German?), but it’s possible they’re not meant to be intelligible—just a further indicator of God’s mysteriousness. The artist has also deliberately chosen not to show God’s face.

Five blue- and red-plumed seraphim—one mostly out of frame, save for one of his wings—stand at the hem of the royal garment, while a sixth flies down toward Isaiah with that burning coal.

At the hem of Christ’s robe is where the woman from Capernaum with the issue of blood finds healing (Luke 8:43–48), and it’s also here at God’s hem that Isaiah is made well, restored.

For a musical complement to Zwerger’s painting, I recommend the song “Lofty and Exalted” by Lenny Smith. It’s from 1993, but Smith didn’t release a recording until 2020, on the album Splendor and Majesty.

Lofty and exalted, reigning from your throne

The train of your robe fills the temple

Seraphim above you, calling out your name

Proclaiming how good and how lovelyRefrain:

Holy, holy, Lord

The earth is full of your glory

Holy, holy, Lord

The earth is full of your praise

“God’s real exalted status and prestige is that He loves being with the lowest of the low,” Smith writes on the song’s Bandcamp page. And in the YouTube description for the song, he reminisces, “Oh for the days when a bunch of us just got together in my basement and just played and sang for hours . . . to our hearts’ content. We had no ulterior motives at all. It was just fun and exhilarating. No audience or pastors or video cameras or aspirations to become worship leaders or famous artists. Oh for those simple, lovely days!”

Smith was involved in the Jesus Movement of the 1960s and ’70s. He has written some two hundred church songs, the most famous of which is “Our God Reigns.” I know him best for “But for You,” through the cover by the Welcome Wagon on their debut album.

Stylistically, this musical adaptation of Isaiah 6 is much different from John Stainer’s. The composition is simple, just a few chords and easily singable (it would work great congregationally), and the instrumentation consists of guitar and piano. It’s also exuberant in tone. Perhaps Stainer’s piece better holds the gravitas of Isaiah’s vision, but Smith’s captures its joy.

In his Prophecy of Isaiah: An Introduction and Commentary, J. Alec Motyer writes, paradoxically, that God’s “transcendent holiness is the mode of God’s immanence, for the whole earth is full of his glory” (77), reminding us that however otherworldly this mystic moment might have felt to Isaiah, the glory of God is profoundly thisworldly too, suffusing the everyday. “God’s glory isn’t ‘up there’ away from us,” writes SALT Project in their lectionary commentary for this Sunday, “but rather fills the whole earth and is intimately, actively involved in our lives, calling and sending us in service to God’s mission in the world.”

Smith gives permission for the use of “Lofty and Exalted” in church contexts; it’s #3248380 on CCLI, and the lead sheet can be found here.

Every artistic interpretation—visual, musical, or what have you—of a scripture text has the potential to open us up to the text in new ways. No single interpretation should become totalizing; we need all kinds! I’m so appreciative of those who take the time to sit with a Bible passage and then respond to it in paint or in song, whether that be medieval monks laboring away in the scriptorium with their gold leaf and color pigments or contemporary storybook illustrators with their watercolors, a Victorian organist knighted by the queen and serving a cathedral or folk musicians jamming with friends in informal, at-home worship.