“Poor fighter, poor sufferer,”

my brother’s words for me.

Self-pity—

I have to beat it down. But how, exactly?

Never know when the next attack will come.

How to suppress religion?

Down the cloisters of the sick it beckoned—

I abused my God . . . that lithograph of Delacroix’s,

irredeemable sheets I flung in the paint and oil,

his Pietà in ruins.

Reconstruct it from memory.

Good technical exercise. Start with the hands,

there were four hands, four arms in the foreground—

mother and son, and the torsions of their bodies

almost impossible, draw them out—

painfully . . . no measurements—

into a great mutual gesture of despair.

Delacroix and I, we both discovered painting

when we no longer had breath or teeth.

Work into his work, strain for health,

the brain clearing, fingers firmer,

brush in the fingers going like a bow,

big bravura work—pure joy! I copy—

no, perform his masterwork of pain.

Genius of iridescent agony, Delacroix,

help me restore your lithograph with color.

I mortify before your model—

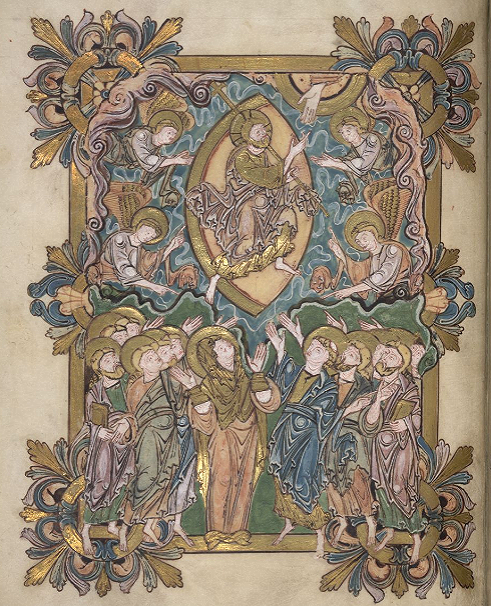

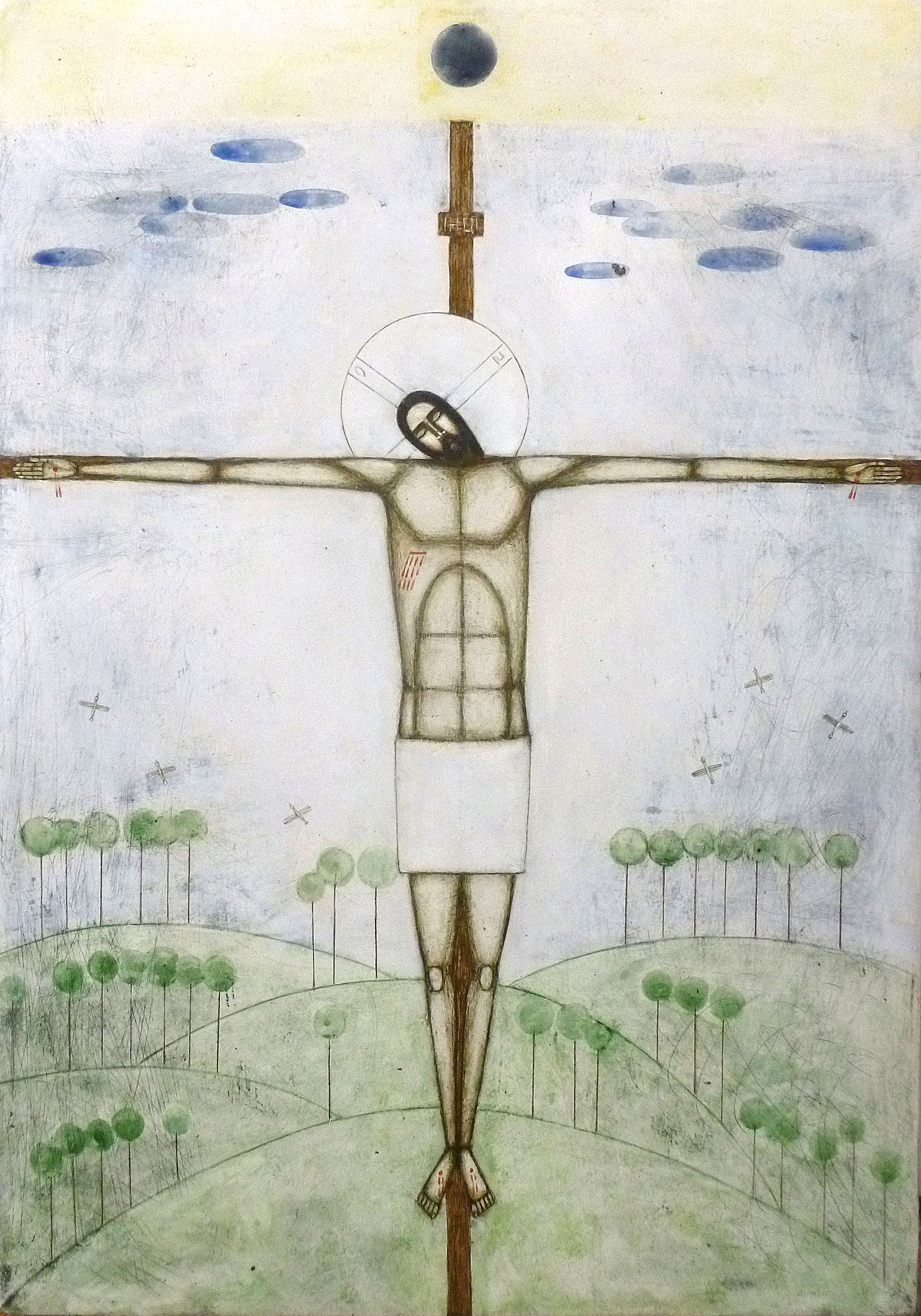

how to imitate my Christ? The bronze

of my forelock shadows his, the greatest artist:

stronger than all the others, spurning marble,

clay and paint, he worked in living flesh.

Living and yet immortal, Lord, revive me—

let me inhale the blue of Mary’s cape

billowing hurricanes of hope, clothe me

in your cerements gold with morning—

mother and son, from all your sorrow

all renewal springs, the earth you touch

turns emerald as your hand that burgeons green.

from I, Vincent: Poems from the Pictures of Van Gogh by Robert Fagles (Princeton University Press, 1978)

Robert Fagles (1933–2008) (PhD, Yale) was an award-winning American translator, poet, and academic. He is best known for his many translations of ancient Greek and Roman classics, especially the epic poems of Homer. He taught English and comparative literature at Princeton University from 1960 until his retirement in 2002, chairing the department from 1975 onward.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) was raised in the Dutch Reformed Church, the son of a small-town minister—and even worked himself as a lay preacher in the Borinage mining region of southwestern Belgium for two years in his mid-twenties. While there, he gave away all his possessions and lived in poverty like those he served, eating a spare diet, wearing rough garments, and sleeping on the floor. Ironically, his sponsoring evangelical committee deemed such behavior unbecoming of a minister of the gospel, and, due also to his lack of eloquence and theological refinement, they withdrew their support.

This rejection soured Vincent on institutional Christianity. But it didn’t squash his faith. After moving back in with his parents in Nuenen, the Netherlands, he wrote to his brother and close confidante, Theo:

Life [. . .] always turns towards one an infinitely meaningless, discouraging, dispiriting blank side on which there is nothing, any more than on a blank canvas.

But however meaningless and vain, however dead life appears, the man of faith, of energy, of warmth, and who knows something, doesn’t let himself be fobbed off like that. He steps in and does something, and hangs on to that, in short, breaks, ‘violates’ – they say.

Let them talk, those cold theologians. [Letter 464]

Although Vincent left the church and developed conflicted feelings about the Bible, he maintained a reverence for Christ to the end of his days. His time in the Borinage was not for nothing, as it’s there that he discovered, through sketching his parishioners and the surrounding landscapes, his calling to be an artist.

This new vocation was one he ascribed metaphorically to Christ. In a letter to his friend and fellow artist Émile Bernard dated June 26, 1888, Vincent wrote that Jesus’s masterworks are human beings made fully and eternally alive:

Christ – alone – among all the philosophers, magicians, &c. declared eternal life – the endlessness of time, the non-existence of death – to be the principal certainty. The necessity and the raison d’être of serenity and devotion. Lived serenely as an artist greater than all artists – disdaining marble and clay and paint – working in LIVING FLESH. I.e. – this extraordinary artist, hardly conceivable with the obtuse instrument of our nervous and stupefied modern brains, made neither statues nor paintings nor even books . . . he states it loud and clear . . . he made . . . LIVING men, immortals. [Letter 632]

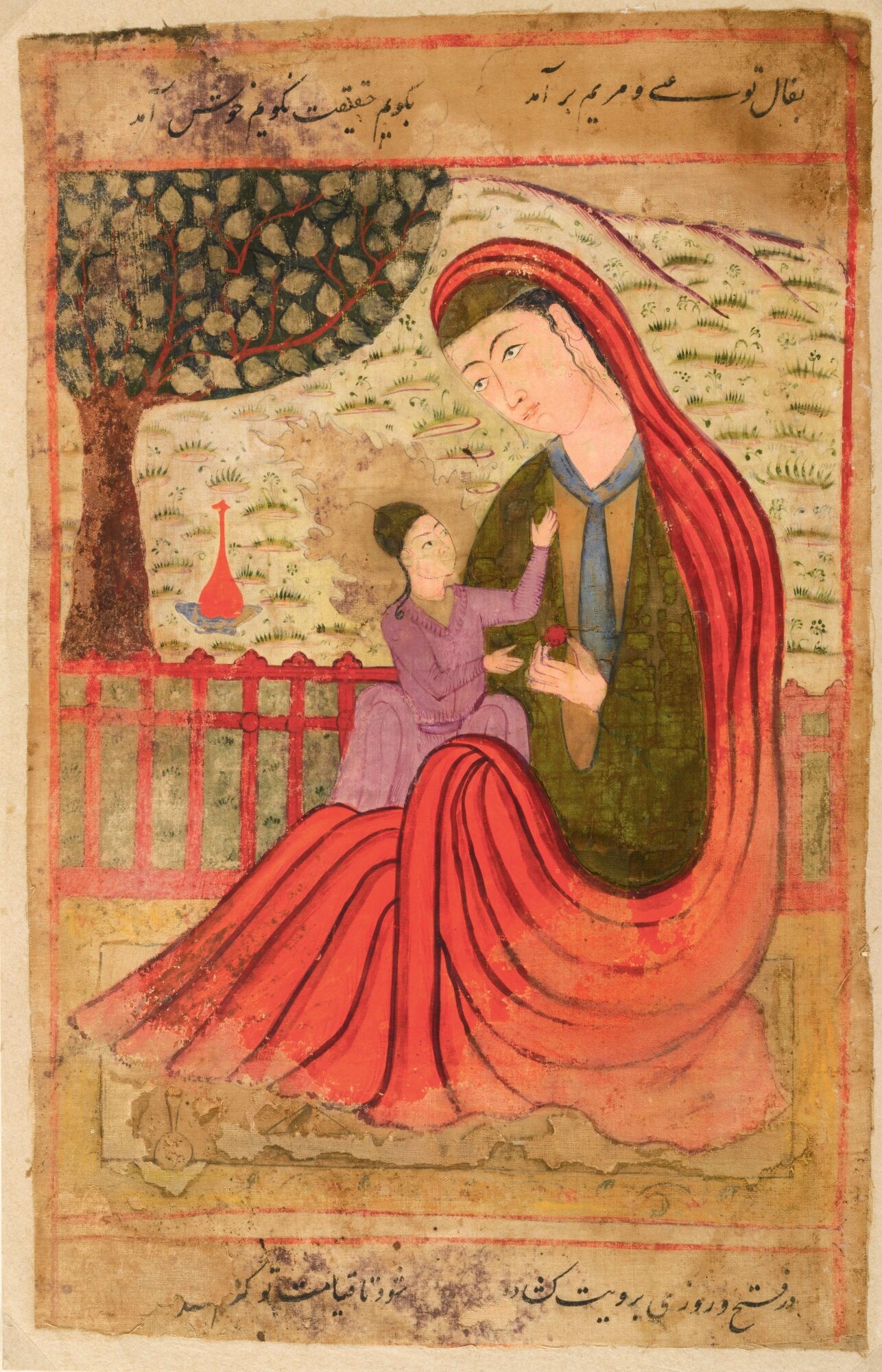

In the same letter, he contended that “the figure of Christ has been painted – as I feel it – only by Delacroix and by Rembrandt…….. And then Millet has painted…. Christ’s doctrine.”

These are the three artists Vincent admired most. He mentions them many times throughout his ample correspondence with family and friends, and he made paintings after all three.

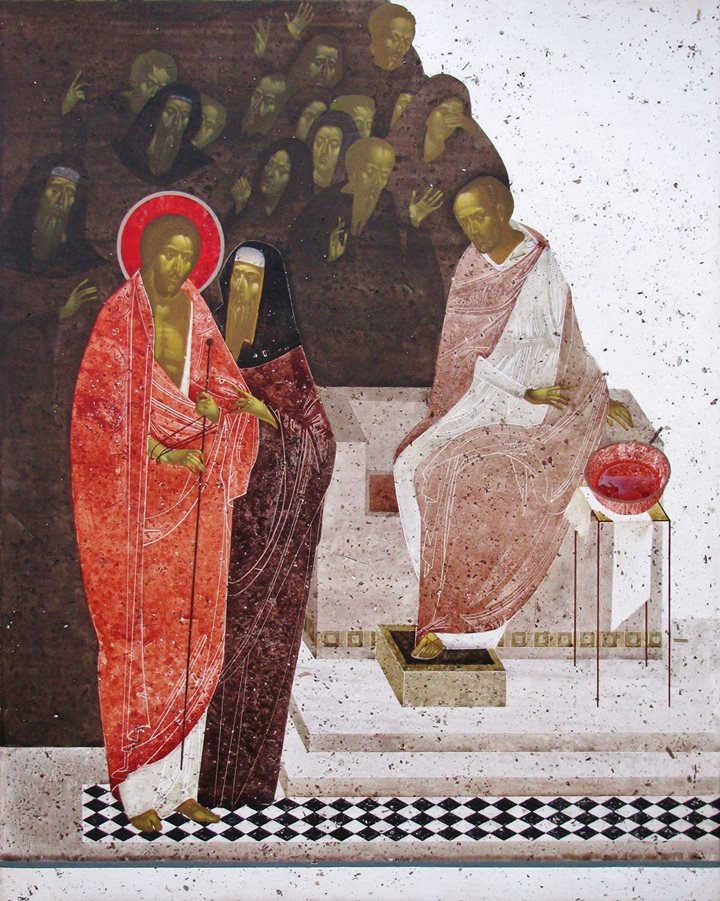

The only painting Vincent ever made of Christ was his Pietà, which he painted in two versions in September 1889, both after the French artist Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). These are among the many works Vincent painted at a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in southern France, to which he had voluntarily committed himself after suffering an acute mental breakdown that resulted in his infamous severing of his left ear on December 23, 1888. Theo had rushed to Arles, where Vincent was living in “the Yellow House” at the time, and on December 28 reported on Vincent’s condition in a letter to his wife, Jo van Gogh-Bonger:

I found Vincent in the hospital in Arles. The people around him realized from his agitation that for the past few days he had been showing symptoms of that most dreadful illness, of madness, and an attack of fièvre chaude, when he injured himself with a razor, was the reason he was taken to hospital. Will he remain insane? The doctors think it possible, but daren’t yet say for certain. It should be apparent in a few days’ time when he is rested; then we will see whether he is lucid again. He seemed to be all right for a few minutes when I was with him, but lapsed shortly afterwards into his brooding about philosophy and theology. It was terribly sad being there, because from time to time all his grief would well up inside and he would try to weep, but couldn’t. Poor fighter and poor, poor sufferer. Nothing can be done to relieve his anguish now, but it is deep and hard for him to bear. [Letter 728]

Vincent returned to the Yellow House in January 1889 but over the next few months experienced recurring bouts of mania and depression and was in and out of the hospital. Some of the people of Arles grew increasingly frightened by his erratic behavior, and they essentially ran him out of town. That’s when he made his way twenty miles northeast to the town of Saint-Rémy to check in to Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, a former monastery that then, as now, served as a hospital for the mentally ill.

(Related post: “Three poems about Vincent van Gogh”)

Vincent had two rooms there, one of which he used as a studio, setting up the various print copies he owned of acclaimed paintings. One was a lithograph by Célestin François Nanteuil-Leboeuf after Delacroix’s Pietà, from the portfolio Les artistes anciens et modernes. (Theo had bought and sent him this litho at his request.) Vincent lamented to his brother that he accidentally damaged it with spilled paint—but that impelled him to paint his own copy of Delacroix. On September 10, 1889, he wrote:

Work is going very well, I’m finding things that I’ve sought in vain for years, and feeling that I always think of those words of Delacroix that you know, that he found painting when he had neither breath nor teeth left. Ah well, I myself with the mental illness I have, I think of so many other artists suffering mentally, and I tell myself that this doesn’t prevent one from practising the role of painter as if nothing had gone wrong.

[. . .] In the very suffering, religious thoughts sometimes console me a great deal. Thus this time during my illness a misfortune happened to me – that lithograph of Delacroix, the Pietà, with other sheets had fallen into some oil and paint and got spoiled.

I was sad about it – then in the meantime I occupied myself painting it, and you’ll see it one day, on a no. 5 or 6 canvas I’ve made a copy of it which I think has feeling. [. . .] My fingers [are] so sure that I drew that Delacroix Pietà without taking a single measurement, though there are those four outstretched hands and arms – gestures and bodily postures that aren’t exactly easy or simple. [Letter 801]

The painted copy he refers to here is the smaller of the two, which he gifted to his sister Willemien and is now in the collection of the Vatican Museums in Vatican City. In another letter, from September 19, he tells Wil “this little copy of course has no value from any point of view,” but “you’ll be able to see in it that Delacroix doesn’t draw the features of a Mater Dolorosa [sorrowing Mother of God] in the manner of Roman statues – and that the pallid aspect, the lost, vague gaze of a person tired of being in anguish and in tears and keeping vigil is present in it.”

The other Pietà that Vincent painted—which is similar to the first but larger and brighter—he kept for himself, hanging it in his bedroom at Saint-Rémy. He describes the painting to Wil:

The Delacroix is a Pietà, i.e. a dead Christ with the Mater Dolorosa. The exhausted corpse lies bent forward on its left side at the entrance to a cave, its hands outstretched, and the woman stands behind. It’s an evening after the storm, and this desolate, blue-clad figure stands out – its flowing clothes blown about by the wind – against a sky in which violet clouds fringed with gold are floating. In a great gesture of despair she too is stretching out her empty arms, and one can see her hands, a working woman’s good, solid hands. With its flowing clothes this figure is almost as wide in extent as it’s tall. And as the dead man’s face is in shadow, the woman’s pale head stands out brightly against a cloud – an opposition which makes these two heads appear to be a dark flower with a pale flower, arranged expressly to bring them out better. [Letter 804]

Although Vincent may have at one time seen Delacroix’s Pietà painting in person, at Saint-Rémy he had only a grayscale image, the lithograph by Nanteuil-Leboeuf, to reference. For his version, he invented his own color scheme—bold blues and yellows.

On September 20, Vincent described to Theo his process of “copying,” or interpreting, the masters:

What I’m seeking in it, and why it seems good to me to copy them, I’m going to try to tell you. We painters are always asked to compose ourselves and to be nothing but composers.

Very well – but in music it isn’t so – and if such a person plays some Beethoven he’ll add his personal interpretation to it – in music, and then above all for singing – a composer’s interpretation is something, and it isn’t a hard and fast rule that only the composer plays his own compositions.

Good – since I’m above all ill at present, I’m trying to do something to console myself, for my own pleasure.

I place the black-and-white by Delacroix or Millet or after them in front of me as a subject. And then I improvise colour on it but, being me, not completely of course, but seeking memories of their paintings – but the memory, the vague consonance of colours that are in the same sentiment, if not right – that’s my own interpretation.

Heaps of people don’t copy. Heaps of others do copy – for me, I set myself to it by chance, and I find that it teaches and above all sometimes consoles.

So then my brush goes between my fingers as if it were a bow on the violin and absolutely for my pleasure. [Letter 805]

Some art historians believe the Christ figure in the painting is a self-portrait—Vincent identifying himself with the suffering Christ, or recognizing Christ’s presence with him in his suffering, and expressing his longing to be cradled in loving arms and for resurrection from the grave of psychosis. In Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings, Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger write,

Nothing could convey more clearly his need to record his own crisis in the features of another than these two copies [of Delacroix’s Pietà]. The face of the crucified Christ in the lap of a grieving Mary quite unambiguously has van Gogh’s own features. In other words, a ginger-haired Christ with a close-trimmed beard was now the perfect symbol of suffering, the (rather crude) encoding of van Gogh’s own Passion. The painter was to attempt this daring stroke once more, in his interpretation of Rembrandt’s The Raising of Lazarus. Here, van Gogh gave his own features to a Biblical figure who, like Christ, passed through Death into new Life. It was as if, in his work as a copyist, van Gogh was pursuing the kind of oblique allegory he disapproved of in Bernard and Gauguin [see Letter 823]. Five weeks of mental darkness demanded artistic expression – and even that incorrigible realist Vincent van Gogh could not be satisfied with landscape immediacy alone. (542)

On May 16, 1890, Vincent left the hospital at Saint-Rémy, bringing his Pietà painting with him. He moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, a suburb of Paris, placing himself under the care of the homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet, who became a friend. Dr. Gachet admired the painting very much and requested his own copy. (As far as we know, Vincent never got around to making one.)

Vincent was incredibly prolific in Auvers, but his mental health continued to decline, and he died a little over two months after relocating there, on July 29, 1890, from a gunshot wound to the lower chest that was likely self-inflicted.

In his poem “Pietà” from an ekphrastic collection based entirely on Vincent’s paintings, Robert Fagles draws on Vincent’s biography and letters in addition to the titular painting to voice the spiritual and emotional yearnings of Vincent’s final year. The last stanza is a prayer that the poetic speaker Vincent addresses to God—for hope, renewal, light:

Living and yet immortal, Lord, revive me—

let me inhale the blue of Mary’s cape

billowing hurricanes of hope, clothe me

in your cerements gold with morning—

mother and son, from all your sorrow

all renewal springs, the earth you touch

turns emerald as your hand that burgeons green.

In Vincent’s Pietà, the dead Christ’s limp hand rests on a grassy boulder or knoll, which Fagles reads as signifying life awakening from death. You can even see the green reflected in Christ’s face and chest, not to mention the golden sun (“after the storm,” as the historical Vincent wrote) glinting on his right arm, abdomen, and shroud, a faint promise of resurrection.