POEM: “Lost Sheep” by Margaret DeRitter: DeRitter writes about a lost Merino sheep in Australia who, because left unsheared for so long, was carrying over seventy-five pounds of wool on his back. He was found in 2021 and rescued by Edgar’s Mission Farm Sanctuary in Lancefield.

+++

SONGS:

>> “What Have We Become” by the Sweeplings: The Sweeplings are Cami Bradley and Whitney Dean, a singing-songwriting folk pop duo. From their album Rise and Fall (2015), “What Have We Become” laments how sin encroaches on our lives—we may welcome it in at first, but then it takes over, makes of our house a wasteland. This theme is embodied by a shadowy, thorny-veiled dancer in the music video.

>> “It Knows Me” by Avi Kaplan: Living outside Nashville, Tennessee, Avi Kaplan is best known for being the original vocal bass of the a cappella group Pentatonix, from 2011 to 2017. This song of self-probing is from his second solo EP, I’ll Get By (2020). It’s about the freedom that comes from reckoning with one’s inner darkness and accepting grace. The animation in the video is by Mertcan Mertbilek.

Kaplan, who is Jewish, wrote on Facebook,

“It Knows Me” is an extremely personal song to me. I believe that everyone has a darker side of them, and that you can choose to play into that, or you can choose to not. This song is about that battle between those two forces, and having a little grace for yourself when you do falter on your path.

>> “Not the Devil Song” by Marcus & Marketo: Marcus & Marketo (Marcus Clingaman and Marketo Michel) are a worship music duo from South Bend, Indiana, fusing the styles of gospel, classical, country, and soul. “Not the Devil Song,” which they wrote in 2019, is about the power Christians are given to tell Satan to back off! When he dangles temptations in front of you, whispers lies in your ear, sows seeds of doubt or fear or hopelessness, you can confidently retort, “Devil, no, you gotta let go; Jesus died to save my soul.”

+++

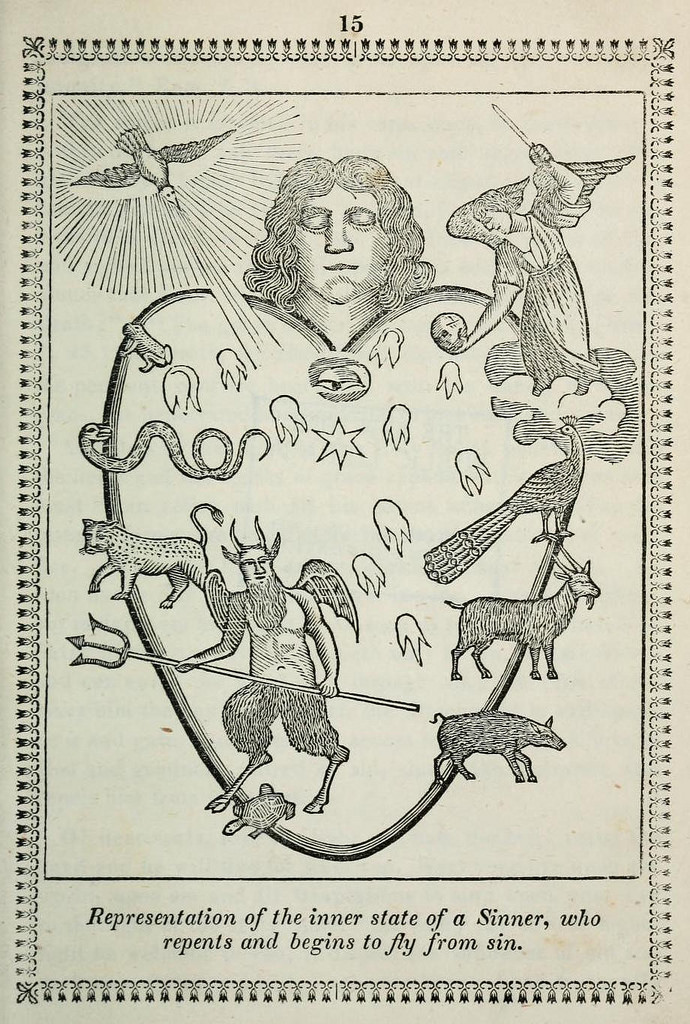

WOODCUT SERIES: Das Herz de Menschen (The Heart of Man): “The following illustrations—which, in a wonderful marriage of word and image, plot out the life of the Christian soul—form the central strain in The Heart of Man: Either a Temple of God, or a Habitation of Satan: Represented in Ten Emblematical Figures, Calculated to Awaken and Promote a Christian Disposition (1851), an English edition of a German book published in 1812 in Berlin by the ‘divine’ and philanthropist Johannes Gossner (1773-1858),” which was itself based on an older French text. The illustrations are not credited and are probably copies of ones that originated in France in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

In his book The Forge of Vision (2015), visual studies scholar David Morgan contrasts this emblematic series with the related Cor Jesu amanti sacrum by Anton Wierix (which I wrote about here). Whereas the Wierix engravings from Antwerp are marked by sweetness, with the Christ child gently cleaning and setting up house in the human heart, the anonymous illustrations Gossner uses portray more of a psychomachia (battle for the soul), with armed angels seeking to oust Satan and his minions.

+++

VIDEO: “How Bermejo paints good and evil in Saint Michael Triumphs over the Devil”: In this nine-minute video, Daniel Sobrino Ralston, associate curator for Spanish paintings at the National Gallery in London, examines a late Gothic painting in the museum’s collection by the Spanish artist Bartolomé Bermejo, showing the archangel Michael slaying Satan. Based on Revelation 12:7–9, this subject gave artists the chance to flex their imaginations in portraying evil incarnate and its vanquishment. Possessing an impressive capacity for fantastical invention, Bermejo gives the devil snakes for arms, eyes for nipples, bird claws, moth-like wings, a spiky tail, and a cactus growing out of its head!

If this visual subject interests you, I recommend the book Angels and Demons in Art by Rosa Giorgi, from the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Guide to Imagery series.