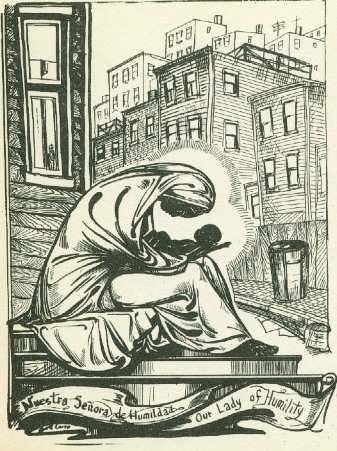

LOOK: Our Lady of Humility by Allan Rohan Crite

Allan Rohan Crite (1910–2007) was a Boston-based African American artist best known for his religious paintings and drawings, many of which place holy personages among everyday people in Boston’s South End. He was Episcopalian.

On using Black figures to narrate biblical stories, Crite said:

I used the black figure in a telling of the story of the Lord, the story of the suffering of the Cross and the whole story of the Redemption of Man by the Lord, but . . . my use of the black figure was not in a limited racial sense, even though I am black, but rather I was telling the story of all mankind through this black figure. (quoted in Julie Levin Caro, Allan Rohan Crite: Artist-Reporter of the African American Community, p. 20)

The image above, which I found years ago at the now defunct brushesandpigments.com with very little captioning info, sets the Nativity in an urban neighborhood. Sitting on a stoop, Mary bends her head down to look lovingly at her son Jesus, cradled in her lap. The banderole at the bottom reads, “Nuestra Señora de Humildad / Our Lady of Humility.”

As indicated by the inscription, this pen and ink drawing belongs to a type of iconography especially popular in the fifteenth century, showing Mary sitting on the ground or on a low cushion, usually holding the Christ child in her lap. The word “humility” derives from the Latin humus, meaning “earth” or “ground.”

I’m not sure why Crite uses Spanish here—whether he spoke it as a second language, or had Spanish-speaking neighbors, or was working on commission—but I do know he visited Mexico and Puerto Rico.

LISTEN: “Poor Little Jesus” (aka “Oh, Po’ Little Jesus”), African American spiritual

Oh, Po’ Little Jesus.

Dis world gonna break your heart.

Dere’ll be no place to lay your head, my Lord.

Oh, Po’ Little Jesus. (Hum)Oh, Mary, she de mother.

Oh, Mary, she bow down an’ cry.

For dere’s no place to lay his head, my Lord.

Oh, Po’ Little Jesus.Come down, all you holy angels,

Sing round him wid your golden harps,

For someday he will die to save dis worl’.

Oh, Po’ Little Jesus. (Hum)

>> Sung by the Morehouse College Glee Club, arr. Leonard de Paur, on New Born King (1999):

>> Sung by Maddy Prior and the Carnival Band, arr. Andrew Watts, on Carols and Capers (1992) (the video below is a live performance from 2004):

>> Arranged and sung by Rev Simpkins (Matt Simpkins), with Martha Simpkins, on Poor Child for Thee: 4 Songs for Christmastide (2020):

I find this spiritual so moving. The five-part harmonies—or even just the two parts in Rev Simpkins’s version—are lush and carry such pathos.

From his humble beginnings in a Bethlehem stable to his ignominious death on a Roman cross, Jesus was no stranger to want and sorrow. He wasn’t impoverished, but he wasn’t wealthy; he had a simple upbringing in the small town of Nazareth. His mother probably longed to give him more than she could. She understood in part the hardship of his calling, knew the rejection he would face—and so she sings, “This world’s gonna break your heart.”

Jesus spent three determinative years of his adult life as an itinerant preacher, traveling from place to place and reliant on the support of others; as he told a scribe who aspired to follow him: “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Matt. 8:19). That ministry culminated in false charges, abandonment, and a public execution.

The Incarnation required vulnerability on the part of God. God chose to make himself susceptible to hurt by entering fully into the life of human struggle. But out of the hurt and struggle that Christ endured came salvation.

“Poor Little Jesus” seeks to stir up pity for Jesus’s plight. Underlying that pity is a thank-you: thank you, Jesus, for taking on our flesh and dealing with our sin, so that we might be free.

The spiritual is not to be confused with another spiritual of the same name (recorded, for example, by Odetta) that goes, “It was poor little Jesus . . . didn’t have no cradle . . . wasn’t that a pity and a shame?”

This post is part of a daily Christmas series that goes through January 6. View all the posts here, and the accompanying Spotify playlist here.