Arise, shine; for your light has come,

and the glory of the LORD has risen upon you.—Isaiah 60:1

But for you who revere my name the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings.

—Malachi 4:2a

LOOK: Christ as Sol Invictus, Early Christian mosaic

This ceiling mosaic from an ancient Roman mausoleum built for one Julius Tarpeianus and his family contains an extraordinary depiction of Jesus Christ modeled after the sun-god Sol Invictus, who was sometimes identified with Helios, Apollo, or Mithras. It’s one of many surviving examples of how the early Christians appropriated pagan iconography for their own use, communicating the sacred stories and truths of the new faith—in this case, Jesus as the light of the world.

Buried beneath St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, the mausoleum was first discovered in 1574 when a workman conducting floor alterations on the cathedral accidentally broke through. A larger hole was then drilled to gain access, which is why this mosaic on its vault is partially destroyed.

The mosaic shows a male figure wearing a radial crown and wheeling through the sky in a quadriga (four-horse chariot)—though just two of the horses survive. He holds an orb, symbolic of his dominion over the earth, and is dressed in a tunic and a windswept cloak. His other hand, missing due to the damage, may have been making a blessing gesture. He sends forth rays in all directions, lighting up the sky with a golden sheen. Grapevine tendrils unfurl all around him, symbolic of life and especially the life-giving Eucharist.

Most scholars identify the image as Christian and read the figure on the sun-wagon as Christ, though this is debated. Other images in the mausoleum are of a fisherman, a shepherd, and a man being swallowed by a sea-monster (e.g., Jonah)—all of which appear in both pagan and Christian funerary contexts in that era.

That December 25 was the birthday of Sol Invictus (and Mithras, a Persian sun-god whose cult gained popularity in Rome in the third century) likely factored into the church choosing that date for the annual celebration of Jesus’s birth. In his book Living the Christian Year: Time to Inhabit the Story of God, Bobby Gross, the vice president for graduate and faculty ministries for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, writes,

Worship of the sun has a long history in ancient cultures. The Roman emperor Aurelian, who apparently wanted to unite the empire around a common religion, instituted the cult of Sol Invictus, the “Unconquered Sun,” in 274 and declared the day of the winter solstice, December 25, as the birthday and feast of the sun-god. [The official date of the winter solstice in the Roman Empire would change to December 21 when the Council of Nicaea adjusted the Julian calendar in 325.] The earliest evidence of Christians in Rome celebrating Christ’s nativity on December 25 appears later in 336. Many scholars conclude that the church purposefully countered the pagan festival by adopting its date for their celebration of the birth of “the sun of righteousness” (Mal. 4:2). This cultural appropriation became an implicit witness to the truly unconquerable light. (66–67)

Other scholars argue that December 25 was chosen because the Feast of the Annunciation—celebrating the miraculous conception of Christ in Mary’s womb—had already been fixed on March 25, the spring equinox, and if you count forward nine months (the average human gestation period), you land on December 25.

These two theories of the dating of Christmas are not mutually exclusive. Christ’s birth was and is celebrated in Rome as a festival of light, so it makes sense that Christians there would mark that birth on the date when the daylight hours first start to grow longer. (Just as it makes sense that his conception was placed in springtime, reflecting the flowering of new life.) Jesus came to us in the depths of our darkness, bringing light. The winter solstice is not an intrinsically pagan event—it’s a natural one, which religions of all kinds find meaning in, not to mention the practicality in ancient societies of marking time by the courses of the sun and the moon.

Many of the church fathers wrote about Jesus as light-bringer and as Light itself. In chapter 11 of his Protrepticus pros Hellenas (Exhortation to the Greeks), written around 200 CE, Clement of Alexandria glories in the light of Christ that extends over all of creation, banishing the darkness. The chapter is editorially titled “How great are the benefits conferred on humanity through the advent of Christ”:

Hail, O light! For in us, buried in darkness, shut up in the shadow of death, light has shone forth from heaven, purer than the sun, sweeter than life here below. That light is eternal life; and whatever partakes of it lives. But night fears the light, and hiding itself in terror, gives place to the day of the Lord. Sleepless light is now over all, and sunset has turned into dawn. This is the meaning of the new creation; for the Sun of Righteousness, who drives his chariot over all, pervades equally all humanity, like his Father, who makes his sun to rise on everyone, and distills on them the dew of the truth. (translated from the Greek by William Wilson, adapt.; emphasis mine)

In chapter 9 of the same work, Clement expounds on Ephesians 5:14, writing, “Awake, he says, you that sleep, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give you light—Christ, the Sun of the Resurrection, he who was born before the morning star, and with his beams bestows life.”

Similarly, Ambrose of Milan refers to Christ as “the true sun” in his Latin hymn “Splendor paternae gloriae,” written in the second half of the fourth century:

O splendor of God’s glory bright,

O Thou that bringest light from light,

O Light of Light, light’s Living Spring,

O Day, all days illumining.O Thou true Sun, on us Thy glance

let fall in royal radiance,

the Spirit’s sanctifying beam

upon our earthly senses stream.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Morn in her rosy car is borne:

let Him come forth our Perfect Morn,

the Word in God the Father One,

the Father perfect in the Son. Amen.Trans. Robert Bridges

Some Christians may feel uncomfortable with Christ’s being made to resemble a pagan deity in the Vatican Necropolis mosaic, or with the suggestion that the church saw fit to celebrate Christ’s birth on the same day Sol Invictus, the “Invincible Sun,” was said to be born. As for myself, I feel no such qualms. Just as the apostle Paul affirmatively quoted the pagan poets Epimenides and Aratus in his Areopagus sermon to reveal the truth of Christ (Acts 17:28), so too can we recognize connection points between our own faith tradition and others, which often reveal common yearnings we share—for example, for light that the darkness cannot overcome.

It’s then for us to articulate what makes Christ, who is such a light, distinct from those who came before and after. He is true God and true man, born miraculously of a virgin in first-century Judaea. He knows our sorrows intimately, because he was one of us—he made himself vulnerable. He taught people how to live as citizens of the kingdom of heaven. For that he was crucified, but he conquered death, rising from the grave and ascending to the right hand of the Father, where he lives and intercedes for us. He will come again to restore us to our true home. This, the story of Christ, is what C. S. Lewis called “a true myth.”

Suggestions for further reading:

- Robin Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2023)

- Kurt Weitzmann, ed., Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979) (available to read online for free)

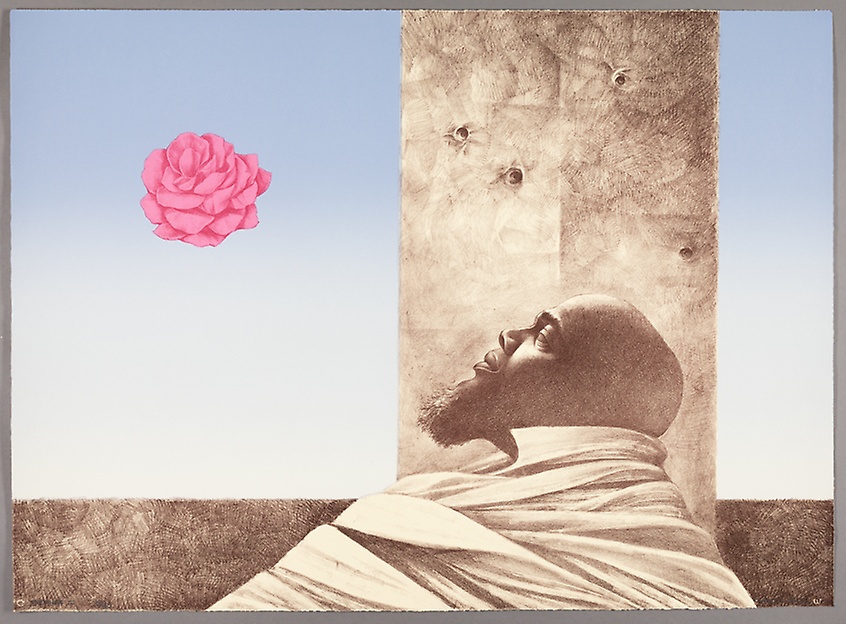

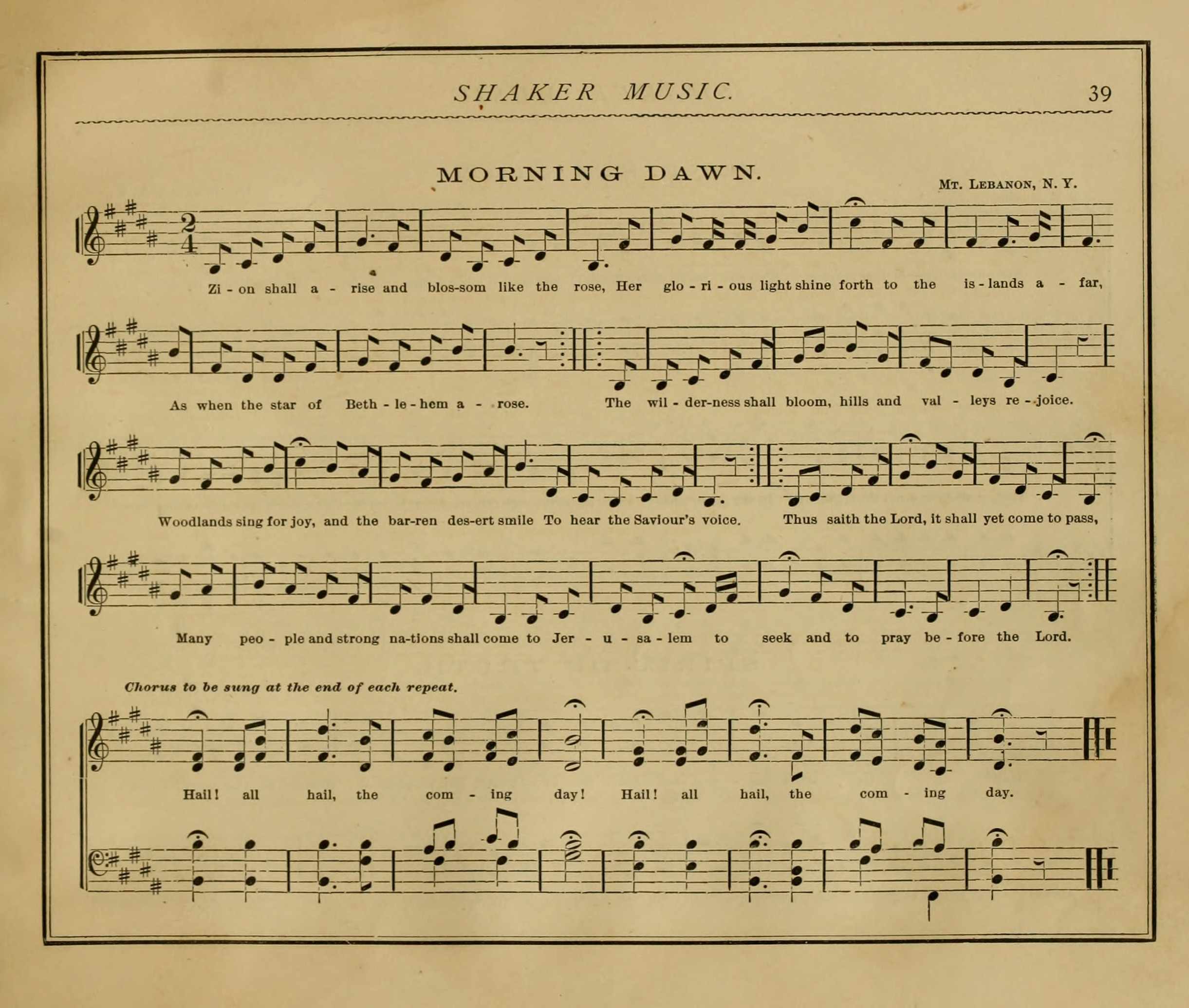

LISTEN: “Rise, Shine, for Thy Light Is a-Comin,” African American spiritual

>> Performed by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, dir. Paul T. Kwami, feat. Briana Barbour, 2016:

>> Performed by the William Appling Singers on Shall We Gather, 2001:

Refrain:

Rise, shine, for thy light is a-comin’

Rise, shine, for thy light is a-comin’

Rise, shine, for thy light is a-comin’

My Lord says he’s comin’ by and byThis is the year of Jubilee

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by)

My Lord has set his people free

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by) [Refrain]I intend to shout and never stop

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by)

Until I reach the mountaintop

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by) [Refrain]Wet or dry, I intend to try

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by)

To serve the Lord until I die

(My Lord says he’s comin’ by and by) [Refrain]

This song originated in enslaved African American communities in the southern US in the first half of the nineteenth century. They composed spirituals as a way to hold on to hope amid the suffering inflicted on them by their enslavers.

The spirituals often hold double meanings, with words like “salvation,” “deliverance,” and “freedom” referring to God’s acts toward the soul and the body. So “freedom,” on the one hand, can mean freedom from sin and eternal death, but it can also mean freedom from physical bondage. “Light” could be the light of the world, Jesus, returning to consummate his kingdom on earth, and it could be the lantern of an Underground Railroad conductor, come to guide you up north to liberation.

The “year of Jubilee” in the first verse refers to the Jubilee law of ancient Israel, which dictates that every fifty years, the enslaved are to be set free (see Leviticus 25). “Wet” in the last verse may refer to how some enslaved people tried to escape by crossing rivers.

“Rise, Shine, for Thy Light Is a-Comin’” exhorts its hearers to take heart, for the sun of righteousness is on its way.