PRINT INTERVIEWS:

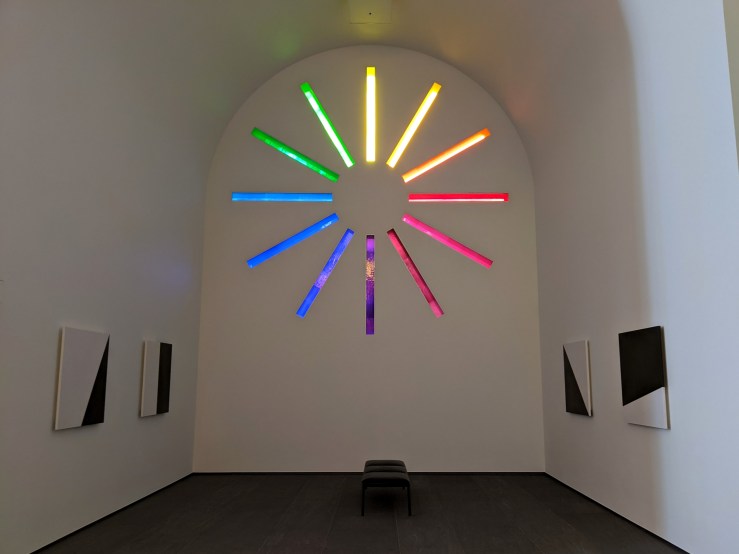

>> “What Remains: The Making of Ellsworth Kelly’s Last Work,” Image interview with Rick Archer: I got to experience Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin—a modernist “chapel” containing three stained glass windows, fourteen black-and-white marble panels (Stations of the Cross), and a redwood totem—while in Texas for a CIVA conference in 2021; see some of my photos below. Kelly was an atheist inspired by Romanesque church architecture, and the architect he chose to collaborate with on Austin, Rick Archer, is a Christian. In this wonderful new interview by Bruce Buescher, Archer discusses his working relationship with Kelly, Kelly’s desire for randomization and form over meaning, the technical and architectural challenges of bringing Kelly’s vision to life, religious references, and the artist’s objective for the space. “I hope when people go in here, they will experience joy,” Archer remembers Kelly saying.

>> “The Invisibility of Religion in Contemporary Art: An interview with Jonathan A. Anderson” by Matthew J. Milliner: Jonathan Anderson [previously] is one of the most important people working across the disciplines of art and theology, and I’m thrilled that his book The Invisibility of Religion in Contemporary Art is now available from the University of Notre Dame Press!

In this recent interview for Comment magazine, Anderson explains his purpose in writing the book:

I have become increasingly convinced that so many pivotal artists and artworks over the past century are deeply shaped by religious traditions and seriously engaged in theological questioning, but this remains severely under-interpreted or misinterpreted in the scholarship about these artists. One might see these threads running through an artist’s artworks and personal writings and even discuss these topics with the artist in their studio, but when one moves to the scholarly writing and teaching about that same artist, that language consistently disappears or is transposed into another register—usually politics, occasionally a highly esoteric spirituality. I wanted to understand, at a non-superficial level, why this was the case, and I wanted to see how other ways of speaking and writing about this topic might be possible.

Don’t miss, at the end of the article, his three hopes for the field of “art and theology,” which I very much share!

+++

LECTURE: “The Problems and Possibilities of Visual Theology: The Ascension as a Case Study” by Jonathan A. Anderson: With Ascension Day coming up on May 29, it’s timely to share this talk given by Jonathan Anderson (see previous roundup item) a few years ago at Duke Divinity School, where he worked as a postdoctoral associate of theology and the visual arts from 2020 to 2023. Anderson explores a handful of images depicting the Ascension of Christ, a particularly challenging subject because of the spatial ambiguity. The scriptural accounts of the event (Luke 24:50–53 and Acts 1:6–11) beg the question, “What does ‘lifted up’ mean? Where is Jesus?” Attempting to work out these spatial difficulties visually can be theologically and exegetically productive, Anderson claims—even if it sometimes leads to unsatisfying results, as, Anderson says, it often does in Western art from the Renaissance onward. By contrast, when artists foster intertextual readings across the biblical canon and focus not so much on what the Ascension looks like as a historical event but rather on what it means, they are generally more successful.

Here are some time stamps, with links to the artworks discussed:

- 15:22: Giotto, Mantegna, Adriaen van Overbeke, John Singleton Copley, etc.

- 22:17: Reidersche Tafel [previously], compared to a Byzantine manuscript illumination of Moses Receiving the Law (brilliant!)

- 30:53: Rabbula Gospels [previously] and a Coptic apse mural

- 38:33: The Ascension by Andrei Rublev: “Fundamental to all [the Ascension icons of the East],” Anderson says, “is the notion that the Ascension doesn’t have much to do with a higher part of the atmosphere (which Western images are continually struggling with) but with an entirely different kind of space. The relevant coordinates here are not down and up, or even higher and lower, but earth and heaven, old creation and new creation.” Anderson’s quotation of Douglas B. Farrow’s Ascension Theology is illuminating!

- 43:51: The Risen Christ (The Ascension) by Rebecca Dulcibella Orpen

- 44:30: Interior of the katholikon (principal church) of Hosios Loukas

- 53:40: Q&A

+++

INSTRUMENTAL JAZZ: “Prayer” by Cory Wong: This video shows a live performance of Cory Wong’s “Prayer” on July 4, 2023, at Gesù music hall in Montreal. Wong, on guitar at far left, is joined by Ariel Posen on guitar, Victor Wooten on bass, and Nate Smith on drums. I learned about Wong through his collaborative album with Jon Batiste, Meditations (2020), which includes a version of this piece featuring Batiste’s piano playing.

+++

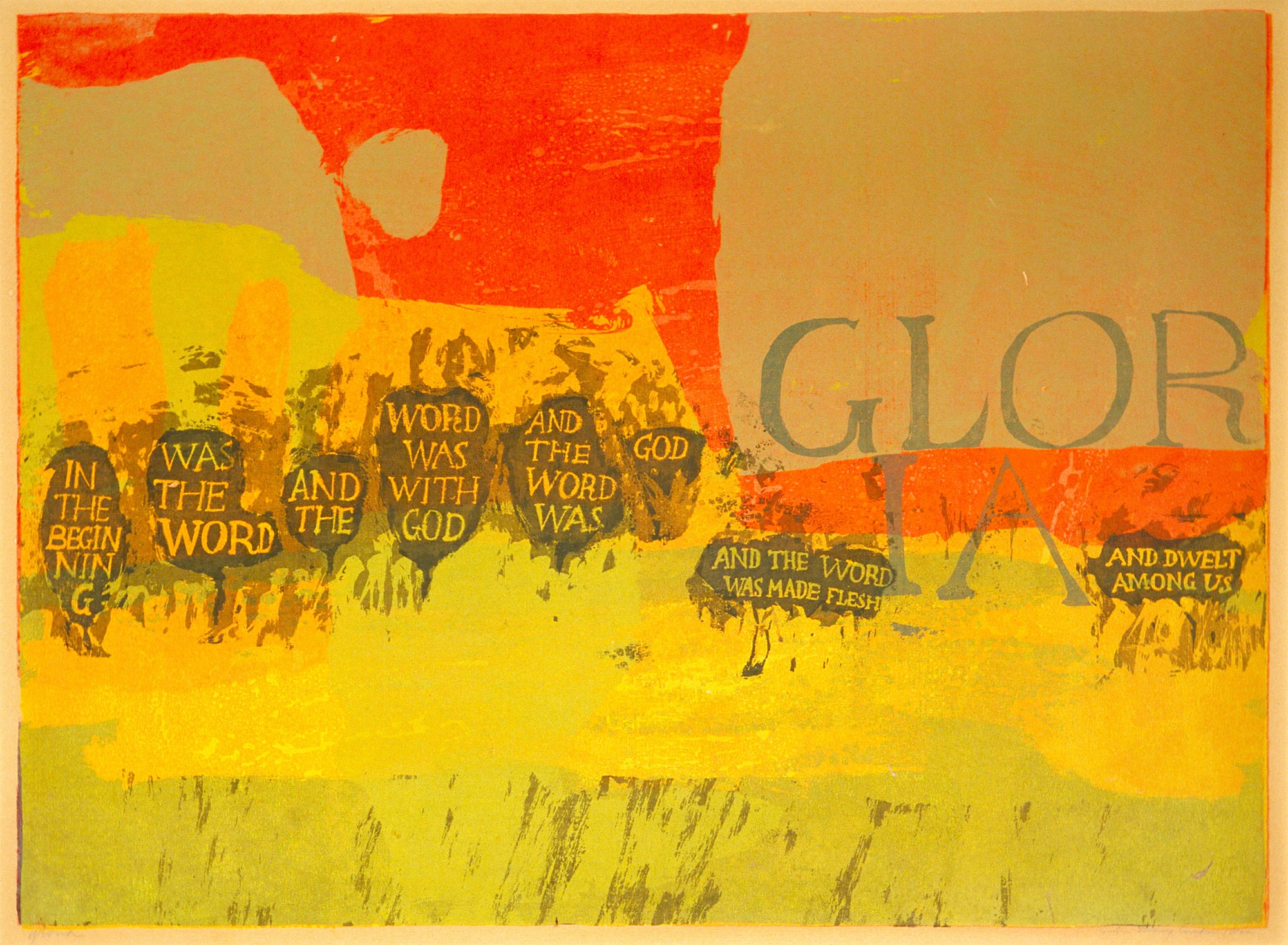

EXHIBITION: OMG! Reli Popart, Museum Krona, Uden, Netherlands, April 5–September 7, 2025: This exhibition at Museum Krona (housed in the complex of the still-active Birgittine Abbey of Maria Refugie in Uden, Netherlands) explores the connection between the pop art movement and Christianity through works by artists such as Andy Warhol, Corita Kent, Niki de Saint Phalle, and especially Dutch artists, including Woody van Amen and Wim Delvoye. Pop art is characterized by the use of imagery from popular culture, sourced from television, magazines, comic books, ads—and sometimes from the trash bin.

Jacques Frenken [previously], for example, built a body of work by salvaging discarded plaster sculptures of Christ and the saints—mass-produced for Catholic devotional use—and reconstructing them into assemblages. For his Spijkerpiëta, he “brought the Pietà back into our midst and accentuated the pain it radiates with nails,” the artist said.

Another artist represented in the exhibition is Hans Truijen, who was commissioned in the 1960s by St. Martin’s Church in Maastricht to design eight stained glass windows for their worship space. The four along the left aisle of the nave depict human and divine suffering, whereas those on the right express hope, love, freedom, and happiness. He chose photographic images from various periodicals, including ones of the Vietnam War, and transferred them to glass using a special screen-printing process.