NEW ALBUM: By Babylon’s River by the Pharaoh Sisters: A folk band from the foothills of North Carolina, the Pharaoh Sisters [previously] are Austin Pfeiffer, Jared Meyer, Kevin Beck, and John Daniel Ray. On September 13 they released their second album, By Babylon’s River, unveiling a new genre they call “saloon Christian.” The title track is a western waltz adaptation of Psalm 137. Also included on the album are a version of Psalm 81 (“Sing, Oh Sing”); bluegrass arrangements of the gospel standards “Leave It There” and “Hold to God’s Unchanging Hand”; retunes of the hymns “All Things Bright and Beautiful” by Cecil Frances Alexander and “’Tis Finished” by Charles Wesley; a cheeky take on the story of Samson, and more.

Here’s the press release.

+++

TRAILER: A Man Called Hurt: The Life and Music of Mississippi John Hurt: Made by directors Jamison Stalsworth and Alex Oliver of Draft creative agency in conjunction with the Mississippi John Hurt Foundation, this documentary about the titular Delta bluesman premiered May 1 at the San Francisco Documentary Festival and has been continuing on the festival circuit; most imminently, it will be screening at the Nashville Film Festival on September 19–25. I’m eager to see it once it hits on-demand streaming or comes to a screen near me! Follow updates at https://www.facebook.com/HurtTheFilm/.

I was introduced to Hurt over a decade ago through his recording of the African American spiritual “I Shall Not Be Moved,” based on Psalm 1. The songs he sang were a mix of sacred and secular.

+++

ARTISTS’ PROFILE: “Sunny Taylor / Jack Baumgartner,” Artful, season 3, episode 6: The BYUtv docuseries Artful, which is available to watch freely online, profiles a variety of artists of faith—many of them Latter-day Saints, but some (non-LDS) Christian or Jewish.

The first half of episode 6, season 3, highlights the work of Sunny Taylor, who lives in Wilton, Maine, and engages with painting’s geometric tradition. She values process over product and wants viewers to observe the surface and textures of her paintings, built up through meticulous layering techniques that involve scraping and grinding. She sees beauty in imperfection, and sorrow and joy as bound up together. Follow her on Instagram @sunnytaylorart.

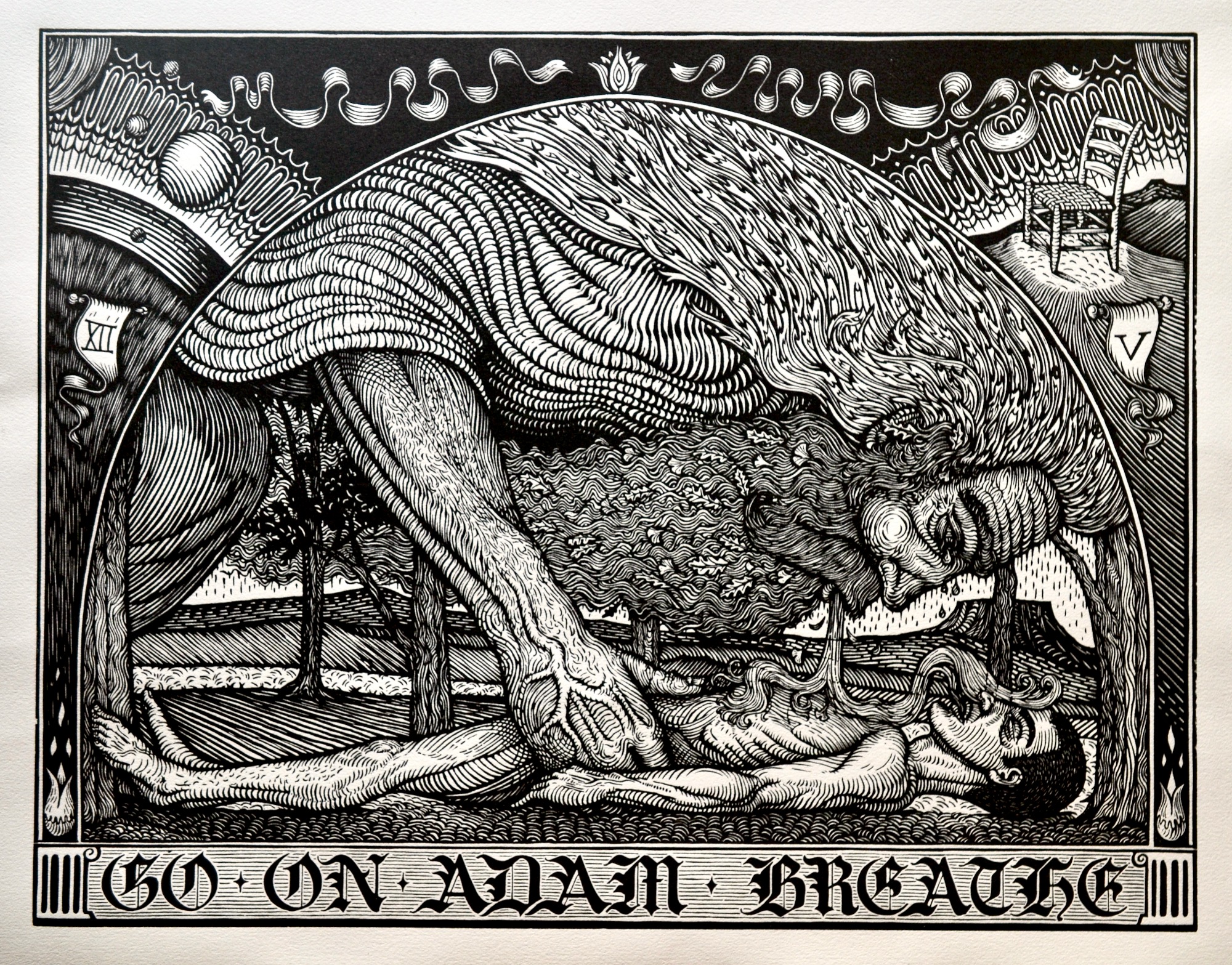

Beginning at the 13:38 time stamp, the second half is on multidisciplinary artist Jack Baumgartner of Kansas. Baumgartner, who has a Presbyterian background, is a printmaker, painter, farmer, woodworker, puppeteer, and musician. He raises sheep, goats, and chickens, builds furniture, plays the banjo, and cohosts the podcast The Color of Dust with two poet friends, “exploring the seen and unseen in the soil of art and agriculture.” He is also a husband and a father of five. I first learned about Baumgartner through an Image journal profile; and Plough published an article about him in 2018. I really enjoyed this twelve-minute video segment that shows him at work and at play in and around his home—especially his puppet theater performance of The Two Deaths of John Beartrist Laceroot! Follow him on Instagram @baumwerkj.

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “Grief and Poetry, with guest Kim Langley,” Faith and Imagination, October 4, 2021: Kim Langley is a certified spiritual director and retreat leader from Ohio; she is also the founder of WordSPA (acronym for “Spirituality Poetry Appreciation”) and author of Send My Roots Rain: A Companion on the Grief Journey (Paraclete, 2019), a compilation of sixty poems interwoven with narrative and commentary, in preparation for which she interviewed some three dozen chaplains, pastors, grief counselors, hospice workers, funeral directors, and bereaved people. She wrote the book after the death of her parents. “I found such comfort in the poems,” she writes, “written by a host of people just like us, picking up their pain, juggling it awkwardly in their arms at first—or maybe for a long time—then gradually finding the resilience to carry it, to know when and how to put it down, when to pick it up, and how to develop strong muscles for the long haul. They helped me carry my pain, and I think they will help you to survive, and maybe even thrive a little.” In this podcast episode, she and the host read and discuss four poems from the book: “Let Evening Come” and “Otherwise” by Jane Kenyon, “Those Winter Sundays” by Robert Hayden, and “Stillbirth” by Laure-Anne Bosselaar.

Launched in 2020, Faith and Imagination [previously] is the podcast of the BYU Humanities Center, hosted by founding director Matthew Wickman. It features interviews with a range of writers, scholars, clergy, and others. View the full archive at https://humanitiescenter.byu.edu/podcast/. And in addition to the Langley episode, let me turn your attention to an excellent recent release with an author I’ve mentioned before: “On Deepening Our Religious Experience: An Invitation to Poetry for the Church, with Abram Van Engen.” You may have heard Van Engen discuss his new book elsewhere, but this interview brings some great insights to the fore.

+++

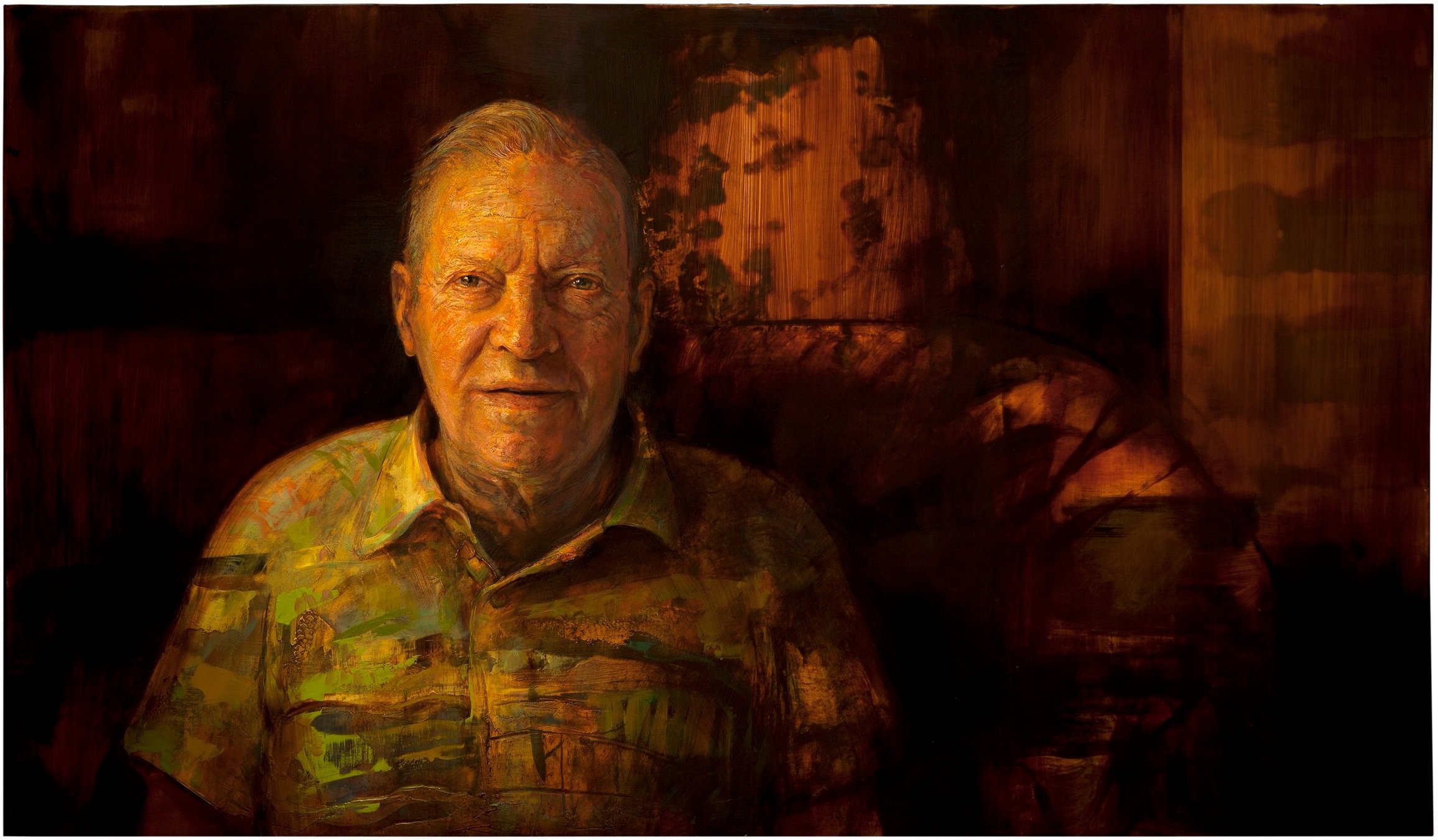

CREATIVE COLLABORATION: Ordinary Saints, a project by artist Bruce Herman, poet Malcolm Guite, and composer J.A.C. Redford: When Bruce Herman’s parents died unexpectedly in 2009, three months apart, painting their portraits was a key way in which he moved through his grief. Poet Malcolm Guite saw Herman’s portrait of his father exhibited at a Christians in the Visual Arts conference in 2011 and, struck by its sheer sense of presence, wrote a sonnet about it. This act of ekphrasis then developed into a three-way collaboration when their mutual friend J.A.C. Redford, a composer, responded by setting Guite’s poem to music.

The basis of Ordinary Saints is a series of portraits Herman painted of family and friends throughout the 2010s, which spawned a series of poems by Guite, which in turn spawned a suite of instrumental music and a song cycle by Redford. The first public presentation of the multidisciplinary project was at a Laity Lodge retreat in the Texas Hill Country on October 26–28, 2018, and it has since traveled to Nashville and Oxford.

The project attempts “to render . . . a glimpse of the glory of our mortal faces when turned toward God . . . faces that point toward the one Face we all must seek,” Herman says. Or, as Guite puts it: “to explore what it means to be truly face to face with one another, how we might discern the image of God in our fellow human beings, and how that discernment might ready us for the time when, as we are promised, we will no longer see ‘through a glass darkly’ but really see God and one another face to face in the all-revealing, and all-healing light of Heaven.”

Here is the title poem, followed by Redford’s title composition for voice, piano, cello, and clarinet:

Ordinary Saints

by Malcolm Guite

The ordinary saints, the ones we know,

Our too-familiar family and friends,

When shall we see them? Who can truly show

Whilst still rough-hewn, the God who shapes our ends?

Who will unveil the presence, glimpse the gold

That is and always was our common ground,

Stretch out a finger, feel, along the fold

To find the flaw, to touch and search that wound

From which the light we never noticed fell

Into our lives? Remember how we turned

To look at them, and they looked back? That full-

Eyed love unselved us, and we turned around,

Unready for the wrench and reach of grace.

But one day we will see them face to face.

Explore more, including readings of all the poems and recordings of the music, at https://ordinary-saints.com/.

+++

POEMS:

>> “Ordinary Sugar” by Amanda Gunn: Pádraig Ó Tuama reads and comments on this food poem in the July 10, 2023, episode of Poetry Unbound. “How can russet potatoes be made to taste of sugar and caramel? By dedication, love, and craft. Amanda Gunn places her poetry in conversation with the farming and culinary skills of her forebears: women who cultivated land, survival, strength, and family bonds.”

>> “Given” by Anna A. Friedrich: This poem by Anna A. Friedrich is a beautiful tribute to her grandmother, Juanita Powell Alphin, who died this June. Friedrich imagines all the gifts her memama ever gave—jump ropes, stuffed animals, homemade fudge, thrift-store doodads, five-dollar bills, a kitten, a plane ticket, etc.—tumbling out onto the golden streets of heaven, a testimony to her generous, loving spirit.