SPOTIFY PLAYLIST: November 2025 (Art & Theology)

Among this month’s thirty spiritual songs of note are three by Indigenous artists of Turtle Island (North America):

>> “Ambe Anishinaabeg” from Cree composer Andrew Balfour’s Nagamo project, which explores the intersections of Indigenous song and Anglican choral music. The Ojibway text of “Ambe Anishinaabeg” was gifted to Balfour by Cory Campbell: “Ambe Anishinaabeg / Biindigeg Anishinaabeg / Mino-bimaadiziwin omaa” (Come in, two-legged beings / Come in, all people / There is good life here). On the album (and the playlist), the text is set to the “Gloria in excelsis Deo” by the late English Renaissance composer Thomas Weelkes; but in another iteration, captured in the following video, Balfour pairs the text with the music of William Byrd’s “Sing Joyfully” (itself a setting of Psalm 81:1–4). (Balfour has also written original music for Campbell’s text.) See the third roundup item for more about Nagamo.

>> “Jesus I Always Want to Be Near to You,” a solo by Doc Tate Nevaquaya (1932–1996) on Native American flute. Nevaquaya, who was Comanche, played an important role in the revival of the Native American flute in the 1970s, expanding the repertoire and playing techniques. This instrumental is one of twelve from the album Comanche Flute Music, originally released in 1979 by Folkway Records, which also includes Nevaquaya’s adaptations of non-Comanche flute melodies, his own compositions, and one piece by his son Edmund. As he states in his introduction to this track, “Jesus I Always Want to Be Near You” is an original Christian hymn written by the Comanche people. I couldn’t find the lyrics, but to listen to some more Comanche hymns, with words, see this video by Comanche Nation tribal members Anthony Nauni and Chad Tahchawwickah, and this recorded gathering at Lawton Indian Baptist Church in Oklahoma.

>> “naká·yè·ʔr sihskę̀·nęʔ (may it be that you have peace)” by Tuscarora singer Jennifer Kreisburg, a song of blessing from the new Yo-Yo Ma EP Our Common Nature. According to Sony Classical, the song expresses “hope for a future where humanity and nature coexist in harmony.” I just started listening to the album’s wonderful companion podcast, for which four of the seven episodes have been released.

+++

Also for November: See my Thanksgiving Playlist [introduction], comprising a hundred-plus songs of gratitude, with a few recent additions at the bottom; and my Christ the King Playlist [introduction], which I made for the final feast of the church year, celebrated Sunday, November 23, this year.

+++

ALBUM: Nagamo by Andrew Balfour: In May and June 2022, the Vancouver-based vocal ensemble musica intima teamed up with composer Andrew Balfour to create Nagamo (Cree for “sings”), a concert and CD recording that reimagines the Anglican choral tradition through an Indigenous lens. A child of the Sixties Scoop, Balfour was born in 1967 in the Fisher River Cree Nation near Winnipeg but at six weeks old was forcibly removed from his birth family by child welfare authorities of Manitoba and adopted by white parents. He says his childhood was happy, and that he was fortunate to have been put in a men and boy’s choir from a young age, where he received a musical education and international travel opportunities; but of course, the sudden rupture from his culture of origin left wounds.

With Nagamo, Balfour seeks to bring together his identities as Cree and as the son of Anglicans of Scottish descent, who raised him in the church (his father was a minister); his love of Renaissance choral music, much of which voices polyphonic praises to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and an Indigenous spiritual sensibility. The album comprises two original compositions (including one in Scots Gaelic), five Renaissance songs retexted (not translated) in Cree or Ojibway, and five unaltered works by William Byrd and Alfonso Ferrabosco. “The concept mines the fantastical question of what might have happened musically should Indigenous and European musics and cultural expressions come together in a manner collaborative and respectful, rather than divisive,” writes music journalist Andrew Scott for The WholeNote.

Examples of the adaptations include “Four Directions,” a recitation in Ojibway of the four cardinal directions—Ningaabiianong (West), Giiwedinong (North), Wabanong (East), Zhaawanong (South)—set to Thomas Tallis’s “Te lucis ante terminum” [previously], a prayer for protection through the night. And “Ispiciwin” (Journey), whose musical basis is Orlando Gibbons’s “Drop, drop, slow tears,” a Christian hymn of contrition, but whose Cree lyrics make reference instead to a smudging ceremony, a sacred cleansing ritual practiced by many Indigenous peoples. Here’s a mini-documentary about the Nagamo project:

Balfour “re-imagines how settler and Indigenous spiritualities can interact with one another. In essence, Balfour imagines a new system of power relations where both spiritualities can co-exist and engage in dialogue without the power imbalances of colonization,” Lukas Sawatsky writes in his master’s thesis Converging Paths: Settler Colonialism and the Canadian Choral Tradition, the final chapter of which explores Nagamo as a case study of “the reclaiming of settler-originated aesthetic models and genres by Indigenous people for their own storytelling purposes.” Sawatsky continues, “Through the lens of the Anglican choral tradition, Balfour synthesises his Indigenous cultural identity into music that proudly celebrates both parts, without resolving their differences. Through this, Balfour looks towards a world where the settlers and Indigenous people can exist without settler colonialism.”

+++

EVENT RECORDING: “A Timbered Choir: The Witness of Creation,” Wheaton College, Illinois, October 28, 2025: Last week the Marion E. Wade Center and the Conservatory of Music at Wheaton College presented “A Timbered Choir: The Witness of Creation,” an evening of music and poetry inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien’s and Wendell Berry’s love of creation and visions of stewardship. Readings and reflections by Wheaton professors from across the disciplines of biology, literature, and art culminated in the world premiere of a new Wade Center commission, a fifteen-minute choral cycle by Josh Rodriguez called A Timbered Choir, which sets to music three poems by Berry. “It was my aim to create a work which captures a sense of awe: at the trees which play such an important role in our fragile ecosystem, at the beauty and life-giving pleasure they provide for us, and at our urgent responsibility to care for them,” Rodriguez explains. “In this three-part tale on the life of trees, the audience is invited to witness an opening lullaby about the birth of the forest, followed by a desperate lament on the destruction of nature’s life-giving biodiversity, and a concluding celebration of nature’s resilience.”

The Wade Center is dedicated to promoting the study of seven British Christian writers: Owen Barfield, G. K. Chesterton, C. S. Lewis, George MacDonald, Dorothy L. Sayers, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams. Wendell Berry—an American poet, novelist, and farmer especially known for his “Sabbath poems,” an expansive series he wrote over decades during his Sunday walks in the woods—is not part of their archive. But Wade Center Director Jim Beitler says they built this recent event around Berry because they want to encourage learners not just to look at the seven authors but to look with them, at the things they cared about. The center identified particular resonance between Berry and Tolkien.

Here are the time stamps from the video recording. The songs are performed by the Wheaton College Concert Choir under the direction of John William Trotter:

- Opening remarks by Jim Beitler, director of the Wade Center

- 7:30: “Nothing Gold Can Stay” by Stephanie Martin (words by Robert Frost)

- 11:02: Reflection by Kristen Page, biologist and author of The Wonders of Creation: Learning Stewardship from Narnia and Middle-Earth

- 18:34: Reflection by Tiffany Kriner, English professor and author of In Thought, Word, and Seed: Reckonings from a Midwest Farm

- 26:44: Reflection by Joel Sheesley, artist

- 34:54: Introducing composer Josh Rodriguez

- 36:08: Statement by Josh Rodriguez

- 45:45: A Timbered Choir by Josh Rodriguez

- 1. How long does it take to make the woods? (1985-V)

- 2. It is the destruction of the world (1988-II)

- 3. Slowly, slowly they return (1986-I)

Also, the Armerding Center for Music and the Arts, where the event was held, is hosting tree-related art in the lobby: Cross of the Feast by Sung Hwan Kim (a crucifix in wood and mixed media made for a past KOSTA [Korean Students All Nations] Conference at Wheaton), permanently installed; and a set of graphite drawings by David Hooker, on display through Christmas break.

+++

ARTICLE: “Regarding the Face of God: On the Paintings, Drawings, and Notebooks of Paul Thek” by Wallace Ludel, Triangle House Review: Last month I wrote about a chalk drawing by Paul Thek that the Archdiocese of Cologne curated for its latest exhibition at Kolumba museum. In preparation for writing, I did some basic research about the artist, who’s best known for his “Meat Pieces,” and was led to this fascinating article that focuses instead on his paintings, drawings, and notebooks, especially the religiosity and contradictions they are charged with.

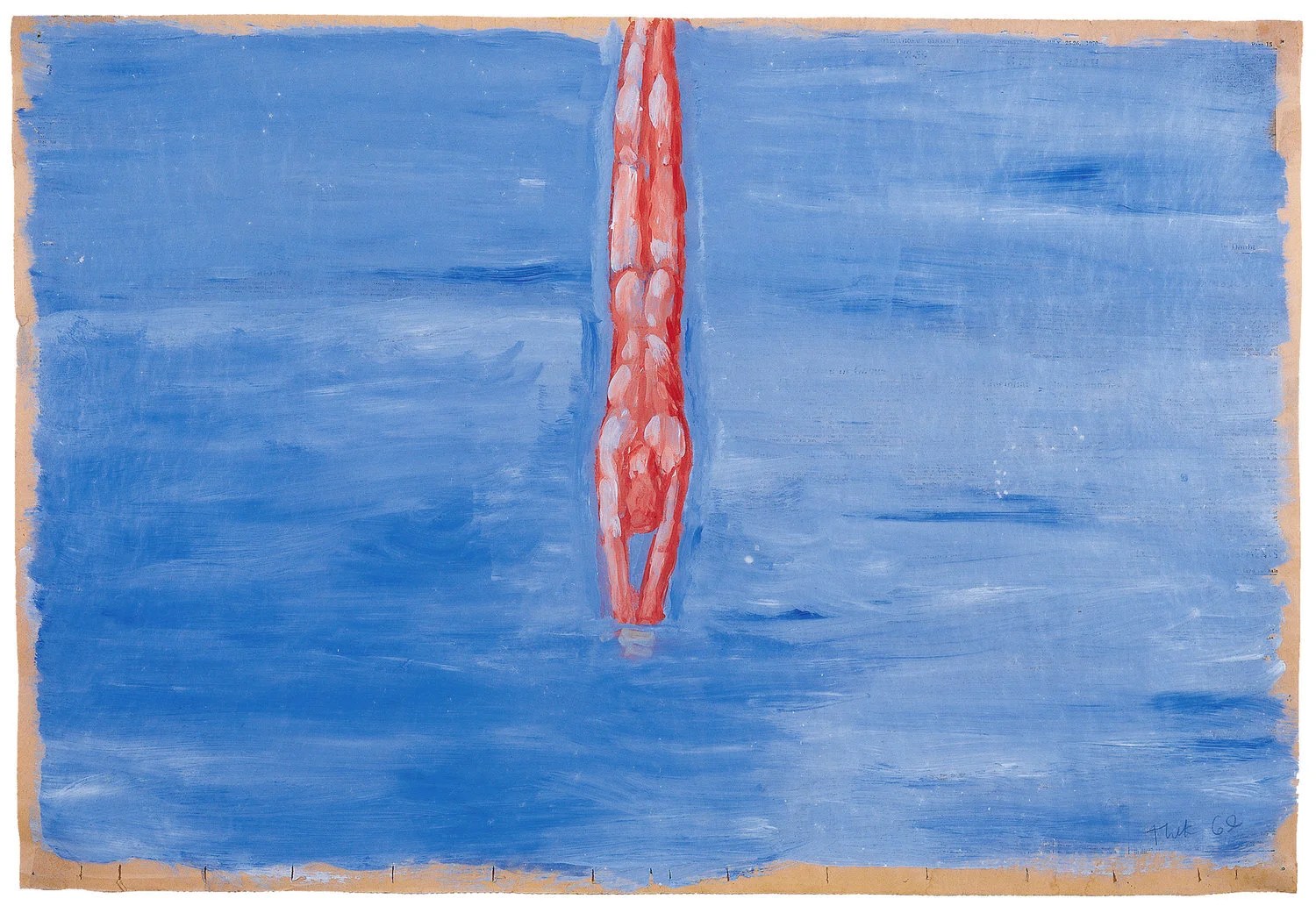

Writer Wallace Ludel describes Thek’s “Diver” paintings of 1969–70, speculated to have been inspired by an ancient fresco inside the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum, Italy, as “at once ebullient and lonesome, womb-like and deathly.”

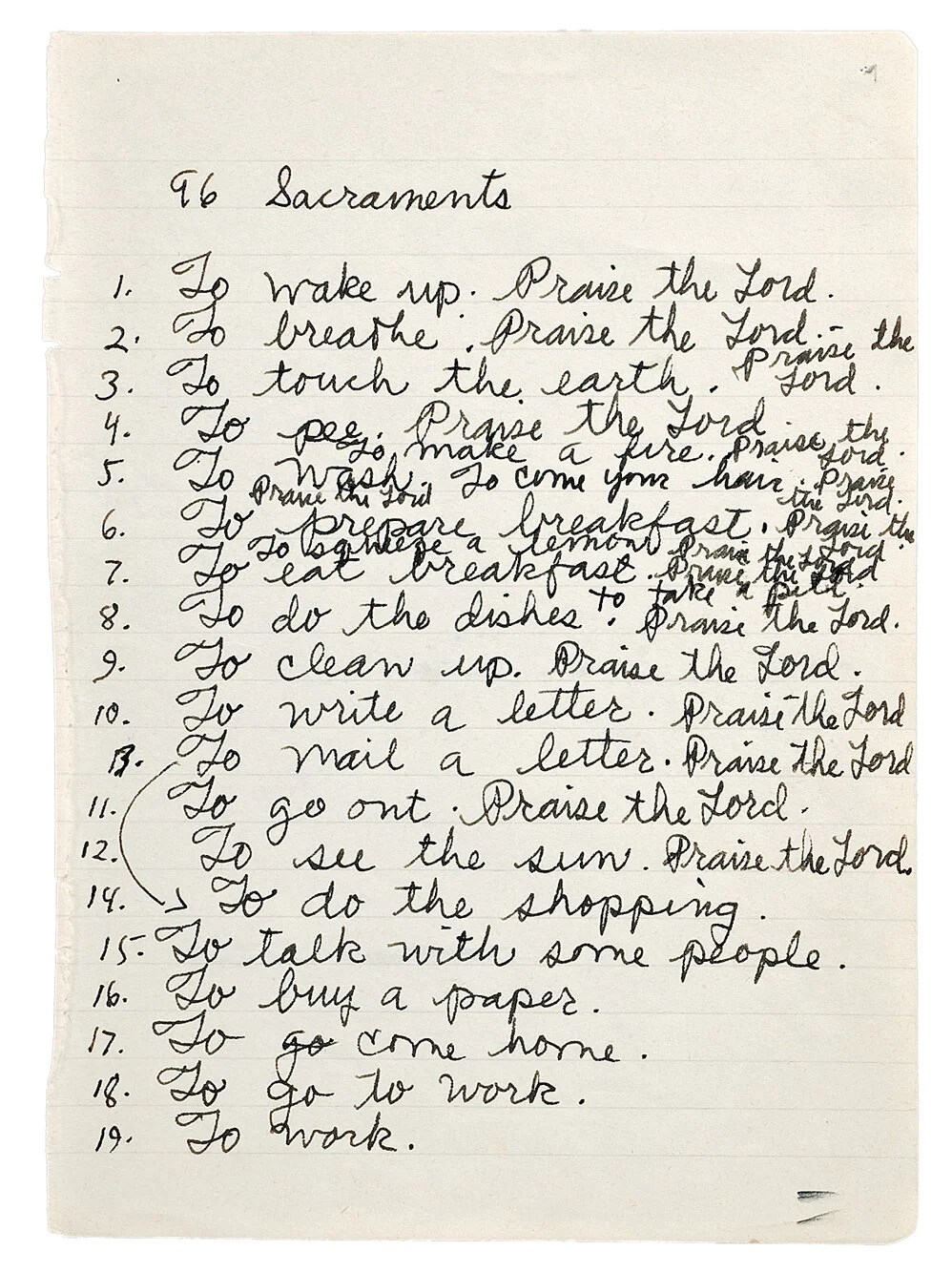

Thek identified as a “predominately gay” Catholic man and was even accepted as a novice by a Carthusian monastery in Vermont shortly before he died of AIDS in 1988. From 1970 onward, he kept notebooks where he copied long passages from spiritual texts and wrote his own devotional musings, as well as made drawings and watercolors and recorded various diaristic thoughts and mantras. One set of the pages, for example, titled “96 Sacraments,” enumerates ninety-six activities—“to breathe . . . to pee . . . to do the dishes . . . to forget bad things . . .”—each followed by the refrain “Praise the Lord.” This list evinces the spiritual influence of Brother Lawrence, who talked about “practicing the presence of God” in all things, which Thek remarked on in a 1984 letter to the Carthusians.

Thek is an artist I had never heard of prior to seeing his work exhibited at Kolumba. Visiting art museums, taking note of the works that intrigue you, and following up afterward with online searches to see and learn more is a great way to develop knowledge of the art that’s out there and to start to identify some of your own personal favorites—which is one of the primary questions I get asked. (“Where do you find all this art?”)