Based at the Faculty of Classics at the University of Oxford, the Manar al-Athar (“Guide to Archaeology”) digital archive provides high-resolution photographs of archaeological sites, buildings, and art from the Levant, North Africa, the Caucasus, and the Balkans, covering the time of Alexander the Great (ca. 300 BCE) through the Byzantine and early Islamic periods, with special emphasis on late antiquity. All the images are freely downloadable, made available for teaching, research, and academic publication under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

Manar al-Athar was established in 2012 by Dr. Judith McKenzie (1957–2019) and since 2020 has been directed by Dr. Ine Jacobs. It is in continuous development. The photos are cataloged by geographical region and are labeled in both English and Arabic. They picture a range of historical structures—some intact, others in ruins; both interiors and exteriors, where applicable—including mausoleums, churches, mosques, khanqahs (Sufi lodges), hammams (public bathhouses), palace complexes, madrasas (colleges for Islamic instruction), forums, fountains, cisterns, aqueducts, civic buildings, theaters, markets, fortifications, and hostels.

Of primary interest to me is the Christian art from churches and tombs, from countries such as Egypt, Syria, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia, and Serbia, and Jewish art that pictures stories from the Hebrew Bible.

Unfortunately, the subjects of the artworks aren’t labeled and there’s no commentary or transcription/translation of inscriptions, nor are the buildings or artworks dated. Inevitably, many of the frescoes and mosaics have degraded with age, sometimes making the iconography difficult to read. There’s also no way to filter by religion; Christianity accounts for only a portion of the images, with others coming from Jewish, Islamic, or pagan traditions, and a number are from nonreligious contexts. I’d love to see a more robust tagging system and advanced searchability functions as the archive continues to evolve.

The archive is by no means comprehensive, but I hope it will encourage further scholarship and attract more digital image donations.

Below is a sampling of the hundreds of images you can find on the Manar al-Athar website.

One of the earliest surviving and best-preserved Christian cemeteries in the world, used by Christians from the third to eighth centuries, is Bagawat Necropolis in the Kharga Oasis in Egypt’s Western Desert. The Chapel of Peace is one of 263 mud-brick funerary chapels in the cemetery, celebrated for the painting of biblical, early Christian, and allegorical figures inside its dome.

The detail pictured above shows the female saint Thecla (Θέκλα), a first-century Christian preacher and martyr, learning from the apostle Paul (Παῦλος), as described in the ancient apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla. They both sit on stools, Thecla holding open a book on her lap, pen in hand, while Paul points out a particular text.

In addition to Paul and Thecla, the dome fresco also depicts, clockwise from that pair: Adam and Eve; Abraham about to sacrifice his son Isaac, with Sarah stretching out her hand (it’s unclear whether this gesture signifies her surrender to God’s will or an attempt to stop her husband’s act); Peace, holding a scepter and an ankh; Daniel in the Lions’ Den; Justice, holding a cornucopia and balance scales; Prayer; Jacob; Noah’s Ark; and the Virgin Annunciate, the New Eve, who heard the word of God and obeyed it and thus brought forth life, unlike her ancestor, who listened to the lies of the Evil One and brought forth death (the snake and dove at the women’s respective ears emphasize this contrast). View a facsimile of the full dome here.

Also in the Egyptian folder are photos of one of Byzantine Egypt’s most glorious encaustic-painted sanctuaries, that of the Red Monastery Church, a triconch (three-apse) basilica that’s part of the (Coptic Orthodox) Monastery of Apa Bishuy near Sohag.

Here’s a video that presents a 3D reconstruction and fly-through of the basilica:

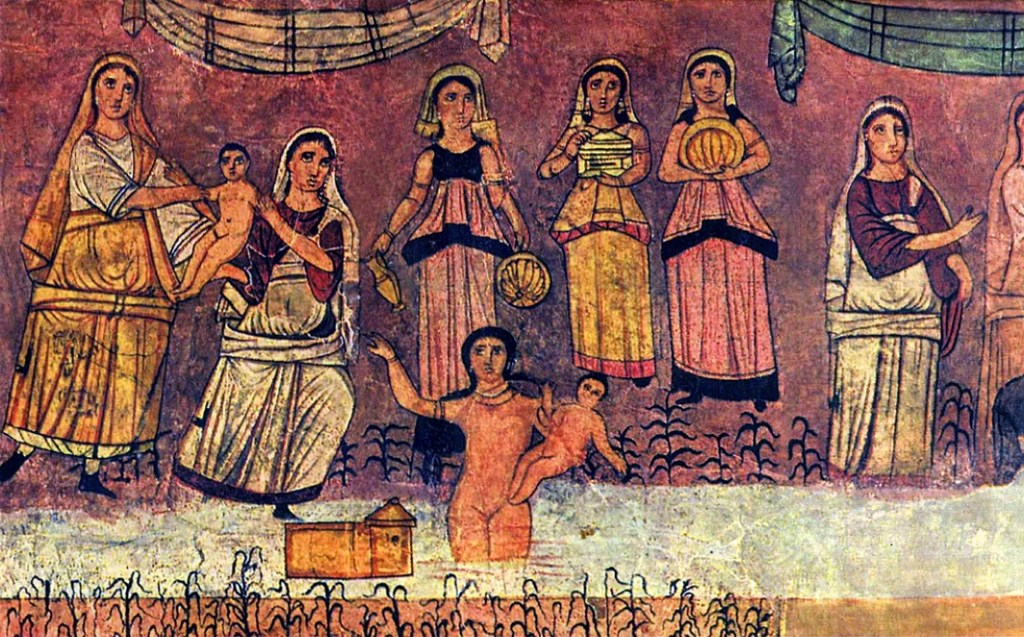

Moving northeast into Israel, we come to the sixth-century Bet Alpha (sometimes rendered as Beit Alfa) Synagogue, located in the Beit She’an Valley. The excavation of Jewish sacred sites like this one reveal that, contrary to what is popularly alleged, Judaism is not a strictly aniconic religion. Many Jewish communities have understood the prohibition against graven images in Exodus 20:3–6 and Leviticus 26:1 as a prohibition against idol worship, not figurative art (art that depicts people and animals) in general. Thus several ancient synagogues, not to mention Jewish manuscripts, portray episodes from the biblical narrative, such as the Akedah (Binding [of Isaac]), told in Genesis 22.

Rendered in a primitive style, this scene is one of three from the mosaic pavement in the central hall of Bet Alpha. It shows Abraham, sword in hand, about to throw his son Isaac onto a fiery altar, when God, represented by a hand from the sky, intervenes, telling him to stop; it’s then that Abraham notices a ram tangled up in a nearby thicket, which he sacrifices instead. The Hebrew inscriptions read, from right to left, “Yitzhak” (Isaac), “Avraham” (Abraham), “al tishlakh” (Do not lay [your hand on the boy]), and “v’hineh ayil” (Here is a ram). Stylized palm trees line the top of the scene.

Here is video footage of the full floor mosaic in its space, showing wide views as well as details, including of the remarkable zodiac wheel in the center:

Mosaic was a common form of late antique decoration in places of worship. Here are two examples from Syria:

To the north of Syria in Turkey—cataloged by Manar al-Athar under “Anatolia,” the ancient name for the peninsula that comprises the majority of the country—there are the Cappadocian cave churches, hewn out of volcanic tufa. They began to be built in the fifth century, with a boom happening in the ninth through eleventh centuries, which is the period to which almost all the surviving paintings can be dated. There are over a thousand such churches, some very simple inside, and others elaborately painted. The architecture has been described as eccentric and enchanting. I like to imagine the monks, nuns, and other Christians who worshipped there all those centuries ago.

One of the cave churches in Cappadocia, part of an ancient monastic settlement, is Pancarlik Church, home to an impressive fresco cycle on the Life of Christ that’s painted mainly in rusty red and bean green.

Beyond Cappadocia but also in Turkey is Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) in Trabzon, not to be confused with the more famous Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, 650 miles away. Originally a Greek Orthodox church, it was converted into a mosque following the conquest of Trabzon (then called Trebizond) by Mehmed II in 1461. During prayer the frescoes in the nave, made by Christians who built and previously occupied the space, are covered by curtains to honor the Islamic prohibition against images—the veils are pulled aside during tourist hours—while the frescoes in the narthex remain uncovered at all times.

One of the frescoes shows Christ appearing to his disciples after his resurrection on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. He hands a fish and a loaf of bread to Peter, who stands at the front of the group, so that they can all share a joyous breakfast together after the tragic, upending events of the previous week.

Another fresco, on the vaulted ceiling of the narthex, shows the four living creatures of Revelation 4—long interpreted by Christian artists as symbols of the Four Evangelists—situated along the four sides of the canopy of the heavens, each holding a golden Gospel-book and surrounded by seraphim and blazes of rainbow light.

In the Caucasus region, Armenia has a long and rich tradition of Christian art, especially relief carving and painting, as the faith took root there early on in the fourth century.

Overlooking the village of Areni on the eastern bank of the river Arpa is the Church of St. Astvatsatsin, which has a beautiful relief carving in the tympanum above the west portal by the Armenian architect, sculptor, and manuscript illuminator Momik Vardpet (died 1333). It depicts the Christ child seated on the lap of his mother, holding a scroll in one hand and raising the other in blessing. Decorative vines rise up behind and around the pair, suggesting verdancy.

The most distinctive Christian art form in Armenia is the khachkar, a carved memorial stele bearing a cross and often botanical motifs, and only occasionally a Christ figure. In the village of Sevanavank, at a different Church of St. Astvatsatsin, there’s a particularly striking khachkar that portrays the crucified Christ in the center, and below that, a scene of the Harrowing of Hell.

Holding aloft his cross as a scepter, the risen Christ breaks down the gates of death and rescues Adam and Eve, representatives of redeemed humanity, while serpents hiss vainly at his heels. I’m struck by the uniqueness of Christ’s hair, which flows down in two long braided pigtails. Was this a common hairstyle for males in medieval Armenia? I have no idea.

The last artwork from Armenia that I’ll share is an icon of paradise from the Church of St. Astvatsatsin (yes, it’s a popular church name in that country!) at Akhtala Monastery.

In the center is the Mother of God flanked by two angels. On the left is Abraham with a child, representing a blessed soul, sitting on his lap (Luke 10:22 describes how the righteous dead go to “Abraham’s bosom,” a place of repose). On the right is Dismas, the “good thief” who repented on the cross of his execution, and to whom Jesus promised paradise (Luke 23:39–43); he is venerated as a saint in the Catholic and Orthodox churches.

The image is part of a larger Last Judgment scene that covers the entire west wall. A few panels above, at the very top, Christ is enthroned on a rainbow.

The neighboring country of Georgia has also cultivated a tradition of Christian icon painting. The main church of Gelati Monastery, founded in 1106, is richly decorated with painted murals dating from the twelfth through seventeenth centuries. One of them is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ: The Virgin Mary gently cradles the head of her son and Mary Magdalene throws her arms up in grief while the apostle John leans in close to mourn the loss and Joseph of Arimathea begins to wrap the body in a shroud.

Another Georgian icon painting, from the central dome of the Church of St. Nicholas in Nikortsminda, shows angels bearing aloft a jeweled cross, surrounded by the twelve apostles.

Lastly, from the Balkans, I want to point out Decani Monastery in Kosovo, a Serbian Orthodox monastery built in the fourteenth century in an architectural style that combines Byzantine and Romanesque influences. The tympana of its katholicon (main church) lean into the Romanesque. The one over the south entrance portrays John baptizing Jesus in the river Jordan, and the Serbian inscription below describes the monastery’s founding.

Decani’s katholicon is the largest and best-preserved medieval church in the Balkans and due to continuing ethnic strife in the region is under international military protection. The Blago Fund website has more and better photos of the extensive frescoes inside, from the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries.

It’s important to note that this is one of a number of churches from the Manar al-Athar archive that are still active sites of Christian worship, where communities of believers are nurtured through word, image, and sacrament.

If you are interested in volunteering with Manar al-Athar—helping with image processing, labeling, fundraising, or web building—or if you have taken any photographs that may be of interest to the curatorial team, email manar@classics.ox.ac.uk.

Website: https://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk/