As important as she is in the Christian tradition, the Bible doesn’t give us a whole lot of details about the life of Mary, especially prior to her conception of Jesus. To give her a backstory and fill in some gaps, the Protoevangelium of James (aka the Gospel of James) was written in the second century, probably in Syria. The author purports to be the apostle James, the brother of Jesus (by an earlier marriage of Joseph’s, according to the text), but the actual author is unknown. While parts of it are based on the canonical Gospels of Matthew and Luke, most of the material is legendary, developed to satisfy people’s curiosity about Jesus’s parentage and some of the events of his infancy.

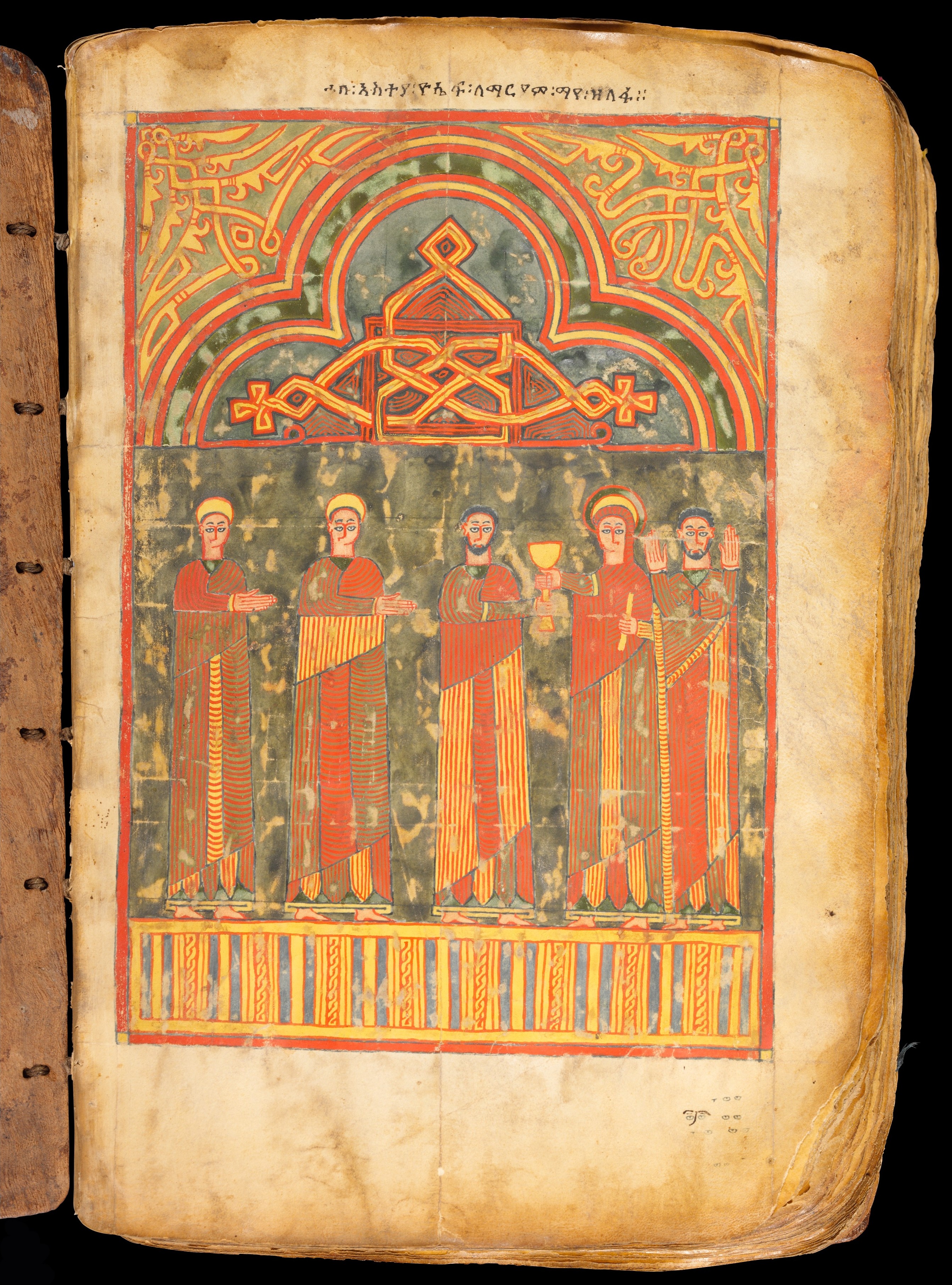

The Protoevangelium of James was, and remains, immensely popular in Eastern Christianity, having been translated early on from its original Greek into Syriac, Ethiopic, Coptic, Armenian, and Arabic. On how the Orthodox Church views the text today, I found this Reddit thread interesting.

A later version of it, with additions and modifications, emerged in Latin by the seventh century under the name the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (aka the Infancy Gospel of Matthew), popularizing its stories in the West.

None of the three branches of Christianity regards these gospels as scripture—the Gelasian Decree of circa 495 officially classified the Protoevangelium as apocryphal, meaning not inspired or authoritative—but nonetheless, they have heavily influenced (in Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy) Christian art and Mariology.

Trying to interpret Christian artworks depicting unfamiliar scenes or details is how I first brushed up against the Protoevangelium of James and the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew.

One such scene, which is rare but sometimes appears between images of the Visitation (or the Annunciation to Mary, or the First Dream of Joseph) and the Journey to Bethlehem, is of Mary standing before a priest, holding a cup. This, I learned, depicts the so-called trial by bitter water, or sotah ritual, an ancient Hebrew method for dealing judicially with women who were suspected of adultery. Outlined in Numbers 5:11–31, in this ritual, a suspicious husband was to bring his wife to the tabernacle to subject her to a trial by ordeal. After receiving a grain offering from the husband, the priest would mix a concoction of holy water, dust from the tabernacle floor, and curses scraped off from the parchment they were written on. The wife would be compelled to swear her innocence and then drink the cup. If she was guilty of marital unfaithfulness, she would suffer painful reproductive affliction;1 but if not, she would be unharmed and thus exonerated.

Trial by ordeal was a common legal recourse in patriarchal cultures across the ancient Near East, reflecting distrust of women’s sexuality and reinforcing husbands’ domination over their wives. That it was a sanctioned practice in the Old Testament is troubling, to say the least—but let’s sidestep that discussion for now. Let me simply commend to you the Numbers 5 visual commentary by Maryanne Saunders (Master of Studies, History of Art, Oxford), which examines three artworks based on this passage, including a feminist Jewish one.

According to the Protoevangelium of James, sometime after the angel had appeared to Joseph convincing him of Mary’s fidelity, a Jewish scribe named Annas saw Mary’s pregnant belly and reported both her and Joseph to the priest for sexual sin, for they were not yet married. They maintained their innocence and were made to drink a potion that would have no effect if they were telling the truth but that would make them ill if they were indeed guilty. Of course, they came out scot-free. Their chastity was divinely confirmed.

(Related post: https://artandtheology.org/2022/12/10/advent-day-14-joseph/)

This account of the Jewish ritual of sotah is unique in that (1) it is initiated by a third party, and (2) the male partner is also accused and made to drink the potential curse. Traditionally, the ritual could be initiated only by a husband. Scholars cite the Protoevangelium author’s apparent unfamiliarity with Jewish practices—this and others—as evidence that he was not Jewish (as the historical James was).

The Protoevangelium was written at a time when opponents of Christianity were decrying the virgin birth. The pagan philosopher Celsus, for example, insisted that while pledged to Joseph, Mary had an affair with the Roman soldier Panthera, and that Jesus was the illegitimate fruit of that union. The story of the trial by bitter water was an attempt to defend Mary against the charge of adultery and Jesus against the charge of ignoble origins. It also—if one believes God was indeed the moral adjudicator in the trial—corroborates the message Mary and Joseph claimed to have received separately from an angel, that Jesus was the Son of God.

I’m sharing this episode from the Protoevangelium not because I think it actually happened but so that you have more context for an image that occasionally crops up in cycles on the life of Mary. Also, perhaps its elaboration on the scandal and consequences of alleged adultery in ancient Jewish culture helps better situate us in Mary’s time and place.

Before I quote the relevant excerpt, a little further background is in order, to explain some of what’s mentioned in the dialogues. Earlier in the Protoevangelium, we read that as an expression of gratitude, Mary’s parents dedicated her to the service of God, and that she lived in the temple in Jerusalem from age three until puberty, where she was fed by angels. When her first menstruation loomed, the priests consulted on what to do with her, lest she defile the temple with her blood. They decided to give her over to the care of Joseph, an elderly widower with grown children.

OK, so now, here are chapters 15 and 16 of the Protoevangelium of James, as translated by Alexander Walker, courtesy of New Advent (I’ve added paragraph breaks):

15. And Annas the scribe came to him [Joseph], and said: “Why have you not appeared in our assembly?”

And Joseph said to him: “Because I was weary from my journey, and rested the first day.”

And he [Annas] turned, and saw that Mary was with child. And he ran away to the priest, and said to him: “Joseph, whom you vouched for, has committed a grievous crime.”

And the priest said: “How so?”

And he said: “He has defiled the virgin whom he received out of the temple of the Lord, and has married her by stealth, and has not revealed it to the sons of Israel.”

And the priest answering, said: “Has Joseph done this?”

Then said Annas the scribe: “Send officers, and you will find the virgin with child.” And the officers went away, and found it as he had said; and they brought her along with Joseph to the tribunal.

And the priest said: “Mary, why have you done this? And why have you brought your soul low, and forgotten the Lord your God? You that wast reared in the holy of holies, and that received food from the hand of an angel, and heard the hymns, and danced before Him, why have you done this?”

And she wept bitterly, saying: “As the Lord my God lives, I am pure before Him, and know not a man.”

And the priest said to Joseph: “Why have you done this?”

And Joseph said: “As the Lord lives, I am pure concerning her.”

Then said the priest: “Bear not false witness, but speak the truth. You have married her by stealth, and hast not revealed it to the sons of Israel, and hast not bowed your head under the strong hand, that your seed might be blessed.” And Joseph was silent.

16. And the priest said: “Give up the virgin whom you received out of the temple of the Lord.” And Joseph burst into tears. And the priest said: “I will give you to drink of the water of the ordeal of the Lord, and He shall make manifest your sins in your eyes.”

And the priest took the water, and gave Joseph to drink and sent him away to the hill-country; and he returned unhurt. And he gave to Mary also to drink, and sent her away to the hill-country; and she returned unhurt. And all the people wondered that sin did not appear in them.

And the priest said: “If the Lord God has not made manifest your sins, neither do I judge you.” And he sent them away.

And Joseph took Mary, and went away to his own house, rejoicing and glorifying the God of Israel.

Here’s how that episode is adapted in chapter 12 of the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew—again, translated by Walker, and in the public domain:

After these things [the angelic announcements to Mary and Joseph] there arose a great report that Mary was with child. And Joseph was seized by the officers of the temple, and brought along with Mary to the high priest. And he with the priests began to reproach him, and to say: “Why have you beguiled so great and so glorious a virgin, who was fed like a dove in the temple by the angels of God, who never wished either to see or to have a man, who had the most excellent knowledge of the law of God? If you had not done violence to her, she would still have remained in her virginity.”

And Joseph vowed, and swore that he had never touched her at all.

And Abiathar the high priest answered him: “As the Lord lives, I will give you to drink of the water of drinking of the Lord, and immediately your sin will appear.”

Then was assembled a multitude of people which could not be numbered, and Mary was brought to the temple. And the priests, and her relatives, and her parents wept, and said to Mary: “Confess to the priests your sin, you that wast like a dove in the temple of God, and received food from the hands of an angel.”

And again Joseph was summoned to the altar, and the water of drinking of the Lord was given him to drink. And when anyone that had lied drank this water, and walked seven times round the altar, God used to show some sign in his face. When, therefore, Joseph had drunk in safety, and had walked round the altar seven times, no sign of sin appeared in him. Then all the priests, and the officers, and the people justified him, saying: “Blessed are you, seeing that no charge has been found good against you.”

And they summoned Mary, and said: “And what excuse can you have? Or what greater sign can appear in you than the conception of your womb, which betrays you? This only we require of you, that since Joseph is pure regarding you, you confess who it is that has beguiled you. For it is better that your confession should betray you, than that the wrath of God should set a mark on your face, and expose you in the midst of the people.”

Then Mary said, steadfastly and without trembling: “O Lord God, King over all, who know all secrets, if there be any pollution in me, or any sin, or any evil desires, or unchastity, expose me in the sight of all the people, and make me an example of punishment to all.” Thus saying, she went up to the altar of the Lord boldly, and drank the water of drinking, and walked round the altar seven times, and no spot was found in her.

And when all the people were in the utmost astonishment, seeing that she was with child, and that no sign had appeared in her face, they began to be disturbed among themselves by conflicting statements: some said that she was holy and unspotted, others that she was wicked and defiled.

Then Mary, seeing that she was still suspected by the people, and that on that account she did not seem to them to be wholly cleared, said in the hearing of all, with a loud voice, “As the Lord Adonai lives, the Lord of Hosts before whom I stand, I have not known man; but I am known by Him to whom from my earliest years I have devoted myself. And this vow I made to my God from my infancy, that I should remain unspotted in Him who created me, and I trust that I shall so live to Him alone, and serve Him alone; and in Him, as long as I shall live, will I remain unpolluted.”

Then they all began to kiss her feet and to embrace her knees, asking her to pardon them for their wicked suspicions. And she was led down to her house with exultation and joy by the people, and the priests, and all the virgins. And they cried out, and said: “Blessed be the name of the Lord forever, because He has manifested your holiness to all His people Israel.”

Some of the differences from the Protoevangelium of James are:

- Mary and Joseph’s accusers are a group of unnamed religious officials rather than the scribe Annas.

- It’s specified that Mary and Joseph are brought before the high priest, and he’s named Abiathar. (In the Protoevangelium, the high priest, from the time of Mary’s presentation in the temple as a child to just after the birth of Christ, is Zechariah, Elizabeth’s husband.)

- The sotah ritual involves the accused circling the altar seven times rather than going away to the hill country and returning.

- Most notably, Mary vows to remain celibate for life. This passage lent power to (or derived power from?) the developing doctrine of Mary’s perpetual virginity—considered dogma by the Roman Catholic Church, as formally declared at the Lateran Council of 649, and taught, too, by the Eastern Orthodox Church, who accept the title “ever-virgin” for Mary, as recognized at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553.

One of the earliest known appearances of the trial by bitter water in visual art is on one of the twenty-seven surviving ivory plaques set into the cathedra (episcopal throne) of Archbishop Maximian of Ravenna.

Standing at the right, Mary holds a vessel in one hand and a skein of wool in the other. (The Protoevangelium says she was among the young women who wove a new veil for the holy of holies.) Joseph stands across from her with a staff in hand, and behind her stands an angel, indicating divine intervention to determine guilt or innocence.

Around the same time, the trial by bitter water appeared in another ivory made in the Eastern Mediterranean—possibly Syria.

And in a sequence of Marian scenes on a carved ivory Gospel-book cover from France.

The scene is found painted inside several of the cave churches of Cappadocia from the ninth through eleventh centuries, including St. Eustathios, Tokalı (see below), Kılıçlar, Bahattin Samanlığı, Aynalı, Eğritaş, and Pürenli Seki, as the art historian Yıldız Ötüken has pointed out.

In Old and “New” Tokalı Kilise (Buckle Church), the latter built as an extension forty years after the original, Joseph drinks the bitter water as well as Mary, as the apocryphal gospels state but which is rarely shown.

So, too, at Çavuşin Church:

But not at Pancarlik Church:

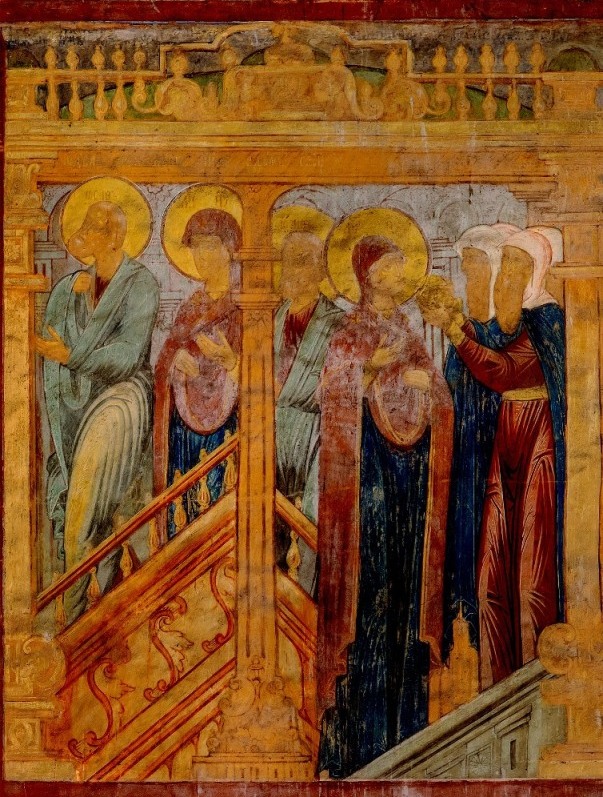

The trial by bitter water also appears elsewhere in the Balkans, such as in Georgia and North Macedonia.

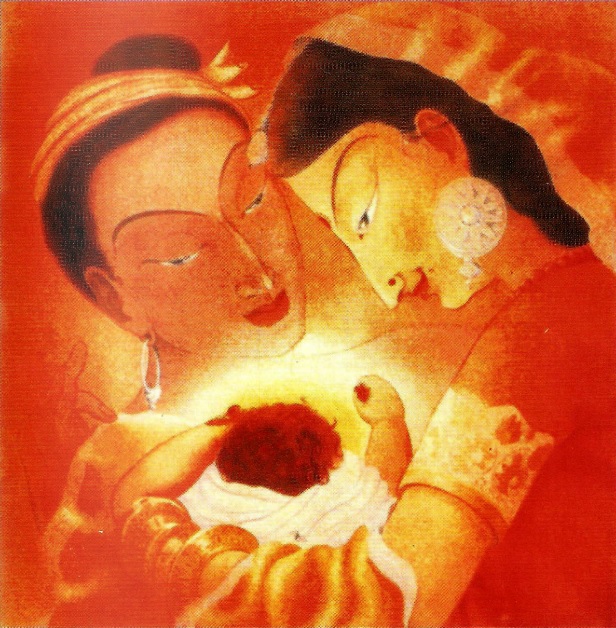

In that second image in the above grouping, Mary is accompanied to the temple by her five (four?) virgin companions, named in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew as Rebecca, Sephora, Susanna, Abigea, and Cael.

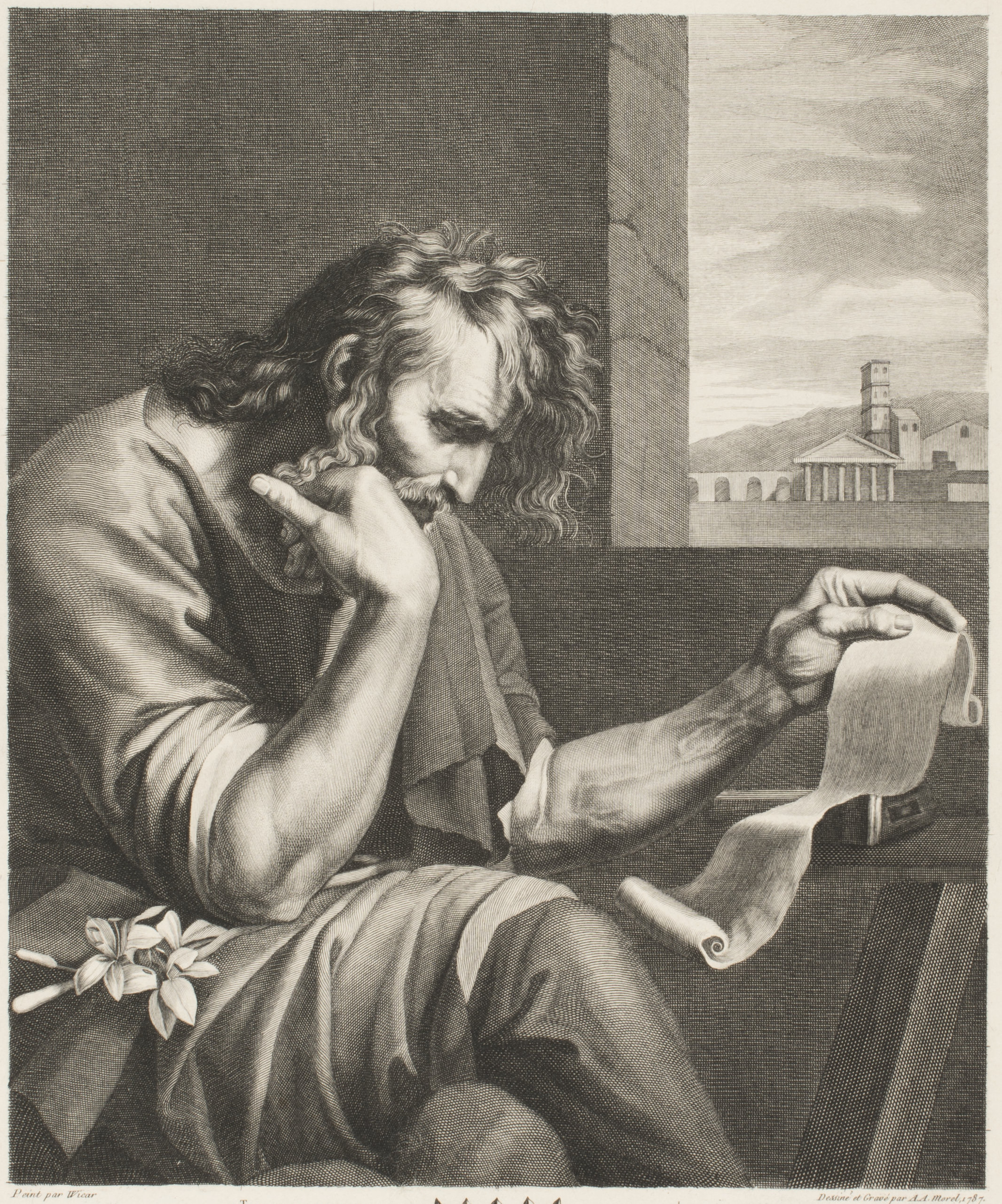

Due to overlapping content, the Protoevangelium of James is illustrated in detail in the twelfth-century manuscript Six Homilies on the Life of the Virgin by James of Kokkinobaphos, which was made by a prominent atelier in Constantinople and is held at the Vatican Library. The trial by bitter water is divided into two separate scenes: one of Joseph drinking the cup and being escorted up the mountain, and one of Mary doing the same.

Other scenes in the sequence portray Joseph’s dream, Joseph consulting with his sons, Joseph apologizing to Mary, Annas the scribe confronting Joseph and the pregnant Mary, Annas reporting the couple to the high priest Zechariah, Mary and Joseph being brought to the temple, Zechariah talking with Joseph, Zechariah talking with Mary, and after the drink, Mary returning unharmed and Zechariah proclaiming her innocence, and then Mary, Joseph, and Joseph’s sons leaving Jerusalem.

On occasion, the trial by bitter water appears in Russian icons, such as on the walls of St. Sophia Cathedral in Vologda.

I first encountered it, though, in my studies of Ethiopian art, where it appears in a handful of illuminated manuscripts.

The trial by bitter water is almost nonexistent in Western art. One exception is a fresco inside the Church of Santa Maria foris portas (Church of St. Mary Outside the Gates) in Castelseprio, Italy. All the frescoes there, which are some of the most sophisticated and expressive to have survived from the early medieval period, exhibit a strong Byzantine influence.

A mosaic at the Basilica of San Marco (Saint Mark’s) in Venice could easily be mistaken for the trial by bitter water, as Mary appears to be taking in hand the same pitcher with which she draws water from the well in the adjacent Annunciation scene.

But the Latin inscription, Quo tingat vela paravit, indicates that the priest is handing Mary a vase of dye. This is another reference to the Protoevangelium: Chapter 10 says that after her betrothal to Joseph but before their marriage, Mary was one of seven virgins from the house of David selected by a council of priests to remake the temple veil (presumably to replace the old worn one). By lot, she was chosen to spin and weave the scarlet and purple.

Other comparable images, such as the mosaic at the former Chora Church (now Kariye Mosque) in Istanbul, show the priest handing Mary a skein of wool instead.

According to the Protoevangelium, Mary was spinning wool for this project when she was interrupted by the angel Gabriel with news of an even greater task she had been chosen for.

Those who disbelieved her about how her pregnancy came to be insisted she be brought to the temple for a trial by bitter water. Sometimes in image cycles on the life of Mary, such as the one on the Carolingian-era Werden Casket, she is shown on her way to the trial rather than at it, being led to the temple by an angel, priest, or moral police to verify her account before God.

Credit goes to Marina Golubina for compiling the vast majority of these images in a blog series (in Russian): Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12, Part 13, Part 14, Part 15, Part 16. As always, I have linked each image to its online source and have done my best to provide captioning info.

NOTES

- When Christians claim that the Bible opposes abortion, some people point to Numbers 5:11–31 as a counterexample, since, for the woman who has conceived a child out of wedlock, the “bitter water” is essentially an abortifacient; “if you have gone astray while under your husband’s authority, if you have defiled yourself and some man other than your husband has had intercourse with you, . . . now may this water that brings the curse enter your bowels and make your womb discharge, your uterus drop!” the priest pronounces (Num. 5:20, 22 NRSV). There’s ambiguity in the Hebrew text as to whether this curse involves loss of a fetus or only infertility. ↩︎