This a continuation of yesterday’s article. In part 1 I shared three room highlights from my visit to Kolumba museum in Cologne, Germany, run by the city’s Catholic archdiocese; in this final part I will do the same for KMSKA in Antwerp, Belgium, whose Old Masters galleries received a “contemporary injection” in an exhibition that wrapped this week. All photos are my own.

[Content warning: This article contains female nudity: a controversial Renaissance painting of the Virgin Mary, and three photographs of women who have just given birth.]

KMSKA, Antwerp

The Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, or KMSKA for short, is a world-famous museum whose collection spans seven centuries, from the Flemish Primitives to the Expressionists.

When I was there last month, the featured exhibition was Collected with Vision: Private Collections in Dialogue with the Old Masters, which ran from April 4 to October 12, 2025. Organized in conjunction with Geukens & De Vil Projects, it interwove postwar and contemporary works by internationally renowned artists from Belgian private collections with the existing museum collection, “expanding the transhistorical approach already in place. The exhibition offers a reflection on the history of art collecting and asks probing questions about social issues such as gender, power and identity. The role of museums and collectors is the focal point. Do the interventions create a harmonious dialogue with 700 years of art history, or do they give rise to challenging contrasts?” Featured artists included Cindy Sherman, Olafur Eliasson, David Claerbout, Francis Alys, Christian Boltanksi, Tracey Emin, Marlene Dumas, Luc Tuymans, and Louise Bourgeois.

The galleries of the exhibition were organized by theme: Holy, Impotence, Horizon, Image, Entertainment, Profusion, Lessons for Life, Fame, The Salon, Heroes, Evil, The Madonna, Suffering, Redemption, Prayer, Heavens, and Power.

I’ll spotlight what I consider the most successful and intriguing pairings.

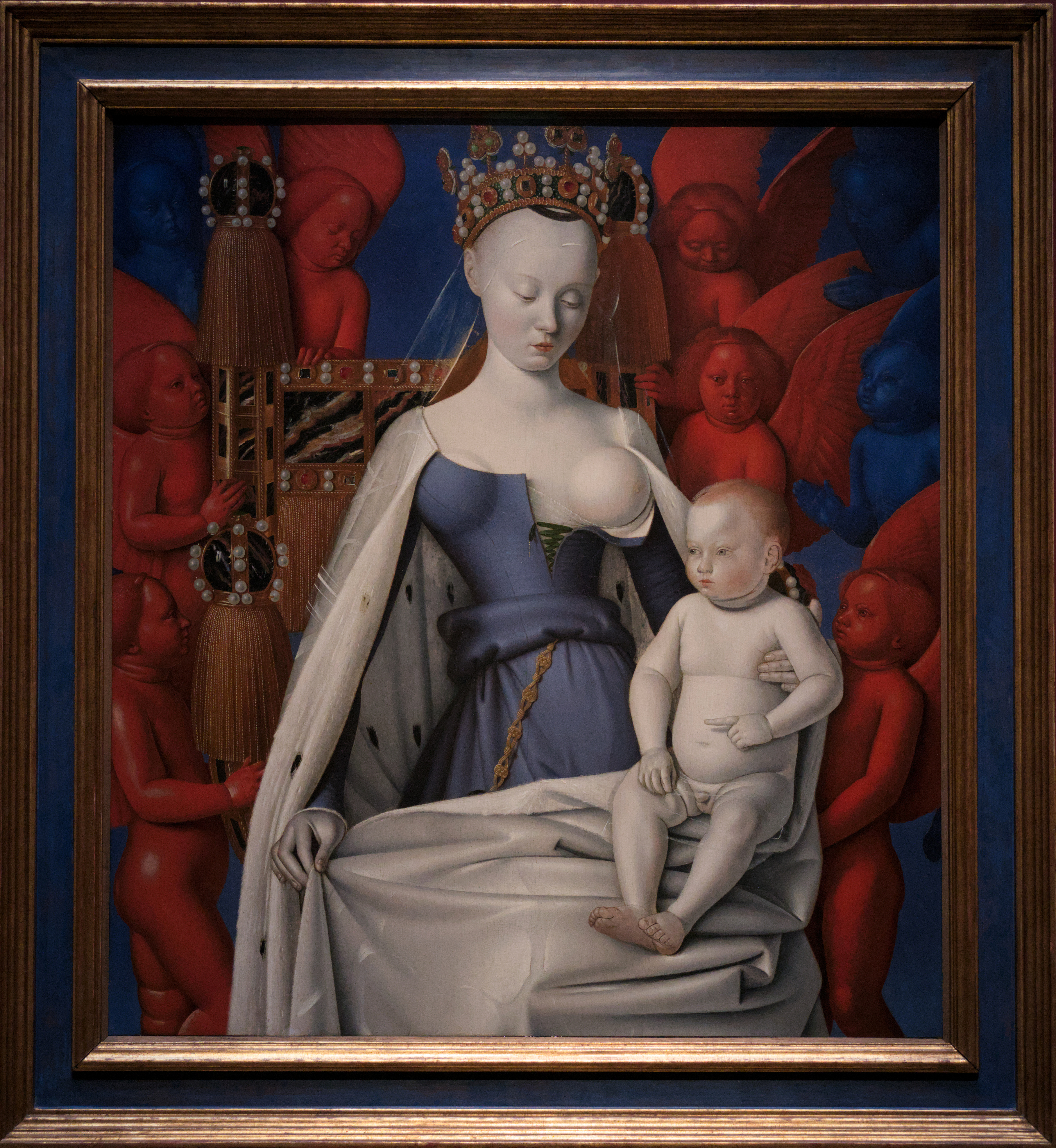

First, the “Madonna” room, anchored by the famous Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim by the late medieval French court painter Jean Fouquet. It’s the right wing of a diptych that originally hung above an altar at the Collegiate Church of Notre-Dame in Melun.

The painting is historically significant—I first encountered it in a college art history course. Commissioned by Etienne Chevalier, treasurer to King Charles VII of France, it portrays the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven, baring her breast ostensibly to nourish the Christ child with her milk. She was probably modeled after Agnès Sorel, the king’s recently deceased mistress and mother of three of his daughters, considered the ideal of feminine beauty at that time in western Europe: pale-skinned, with a high forehead, and fashionable in her ermine cloak.

Though I can appreciate the technical excellence of this painting and the intense reds and blues of the angels, I don’t really like it. Mary seems cold, not very maternal. There’s also an eroticization of her body—not because her breast is exposed, which was common in Marian art, but because it seems to be on display for the viewer; her son’s not interested in feeding—that’s wholly inappropriate for the subject. Why you’d want to memorialize your boss’s sex partner in such a way is beyond me. I’m no prude, but I much prefer Jan van Eyck’s Madonna at the Fountain, on display in the same room:

This small painting originally hung not in a church but in someone’s house. Though there’s still an air of formality, it has all the tenderness and connection that the other one lacks. Mother and son embrace in a garden of roses, irises, and lilies of the valley, he reaching round her neck and holding a string of prayer beads, she gazing adoringly at him. They stand beside a fountain, recalling Jesus’s discussion in John 4 about the “living water” he gives to those who thirst. The original wood frame bears the artist’s motto: “As well as I can.”

The deeply engrained portrait of motherhood embodied by the Virgin Mary is juxtaposed most potently with a series of three black-and-white portraits of new mothers by the Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra.

The accompanying text read:

Jean Fouquet portrays motherhood as something sacred. Mary as a symbol of purity and devotion is richly dressed in cool colours. Rineke Dijkstra homes in on the vulnerable reality. Her mothers are scantily clad and marked by childbirth. Both works are innovative: Fouquet may have painted his Mary for the first time from a real person, and in its day the painting was regarded as ‘modern’. Dijkstra shows motherhood in all its rawness, a taboo usually withheld from view.

Julie wears hospital pads and mesh underwear, which women often do for several weeks after giving birth to manage postpartum bleeding and urinary incontinence. As for Tecla, blood is running down her leg. And Saskia bears a scar from her cesarean section. A linea nigra (dark line) zips down the abdomen of all three, a temporary pigmentation increase caused by increased hormone levels. I love this triptych that shows motherhood’s glorious, messy, alterative impact on the body—the real physicality of the vocation of bearing children into the world.

I wish there were more imagery of Mary like this, as it would, I think, deepen the wonder of the Incarnation and enhance women’s ability to identify with Mary and thus further enliven her story.

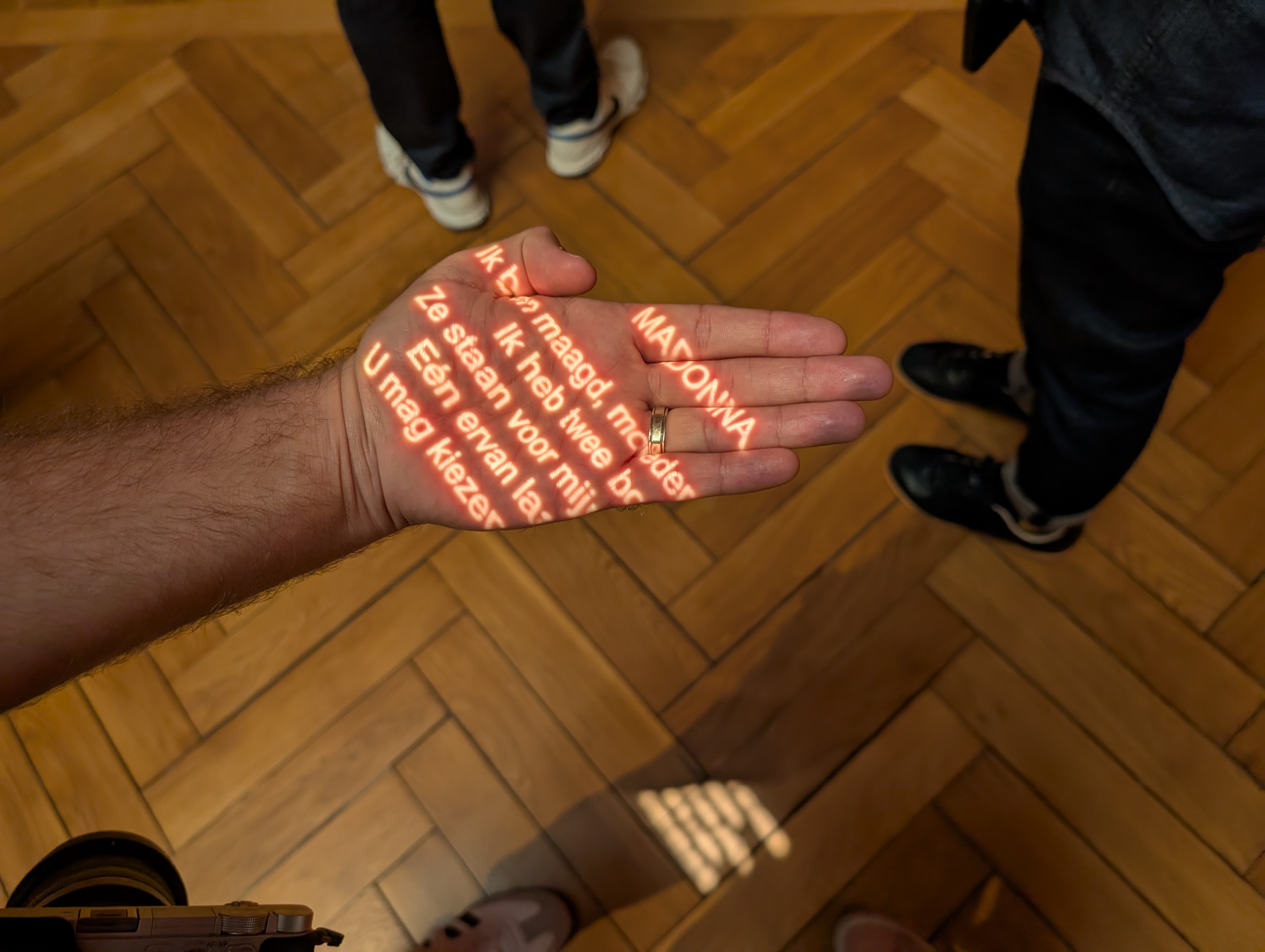

Also in the Madonna gallery was a unique “light poetry” installation by Nick Mattan and Angelo Tijssens—one of seventeen spread throughout the second floor, collectively titled Licht dat naar ons tast (Light that reaches for us). KMSKA had commissioned this couple to bring to life the short verses the museum’s late writer-in-residence Bernard Dewulf had written in response to the galleries’ stated themes.

“Inspired by the museum’s many reading and praying figures, as well as James Ensor’s expressive hand sketches, [Mattan and Tijssens] sought a subtle way to make [Dewulf’s] words tangible,” the museum writes. Their solution was to project them onto the gallery floors from brass cylinders suspended from the ceiling. The words shine like faint specks of light, becoming legible only when a visitor holds their hands, a sweater, or something else up to the light.

Here my husband “holds” a poem written in the voice of Mary:

“Madonna” by Bernard Dewulf

Virgin, mother, wife –

I have two breasts

that stand for my three souls.

I show you one of them,

and whose it is is yours to choose.Translated from the original Dutch by David Colmer

Kind of cheeky! Dewulf speaks of Mary’s three identities and lets us decide if the breast she bares in Fouquet’s painting represents her naked innocence, her nurturing impulse, or her desire to please her husband. (Traditionally in art, it has always stood for the second.)

Though I can’t read Dutch and thus had to consult the KMSKA app for translations of the poems, the thrill of discovery was there in each room. View other visitor engagements with Licht dat naar ons tast on Instagram.

The next gallery I entered was themed “Suffering.”

As one would expect, it’s inhabited by several Old Master paintings of Christ’s passion, most notably a triptych by the Flemish Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens.

The central panel shows the dead Christ being laid out on a marble slab and wrapped in a shroud by Joseph of Arimathea, while his mother and Mary Magdalene (and the apostle John in the background) mourn him. The left wing shows Mary supporting the pudgy little baby Jesus as he takes some of his first steps, while the right wing shows John, whose symbol is the eagle, writing his Gospel that will place Jesus’s death in the context of the larger story of his life of ministry and his resurrection.

This painting, along with Anthony van Dyck’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ and The Holy Trinity by a follower of Rubens’s (which shows God the Father cradling the dead body of God the Son in an image type sometimes referred to as the Mystic Pietà), are juxtaposed with three photographs by Nan Goldin that show the impact of AIDS on her friend, the Parisian gallery owner Gilles Dusein, and his partner, the artist Gotscho.

Dusein’s emaciated arm, resting weakly on a hospital sheet, recalls the limp arm of Christ in paintings of the Deposition and Entombment; and Gotscho’s kiss, the love and grief of Jesus’s mother and friends as they watched their loved one suffer and succumb to death.

By displaying these disparate artworks from vastly different contexts across from each other, we are encouraged to draw connections between the suffering of Christ and that of the LGBTQ+ community. While Christians in Rubens’s day would sit before images of Jesus in pain or sorrow or having died a torturous and untimely death, and deepen their empathy and love, so too might we do well to sit prayerfully, humbly, empathetically, with contemporary images of suffering, seeking to enter the stories they tell.

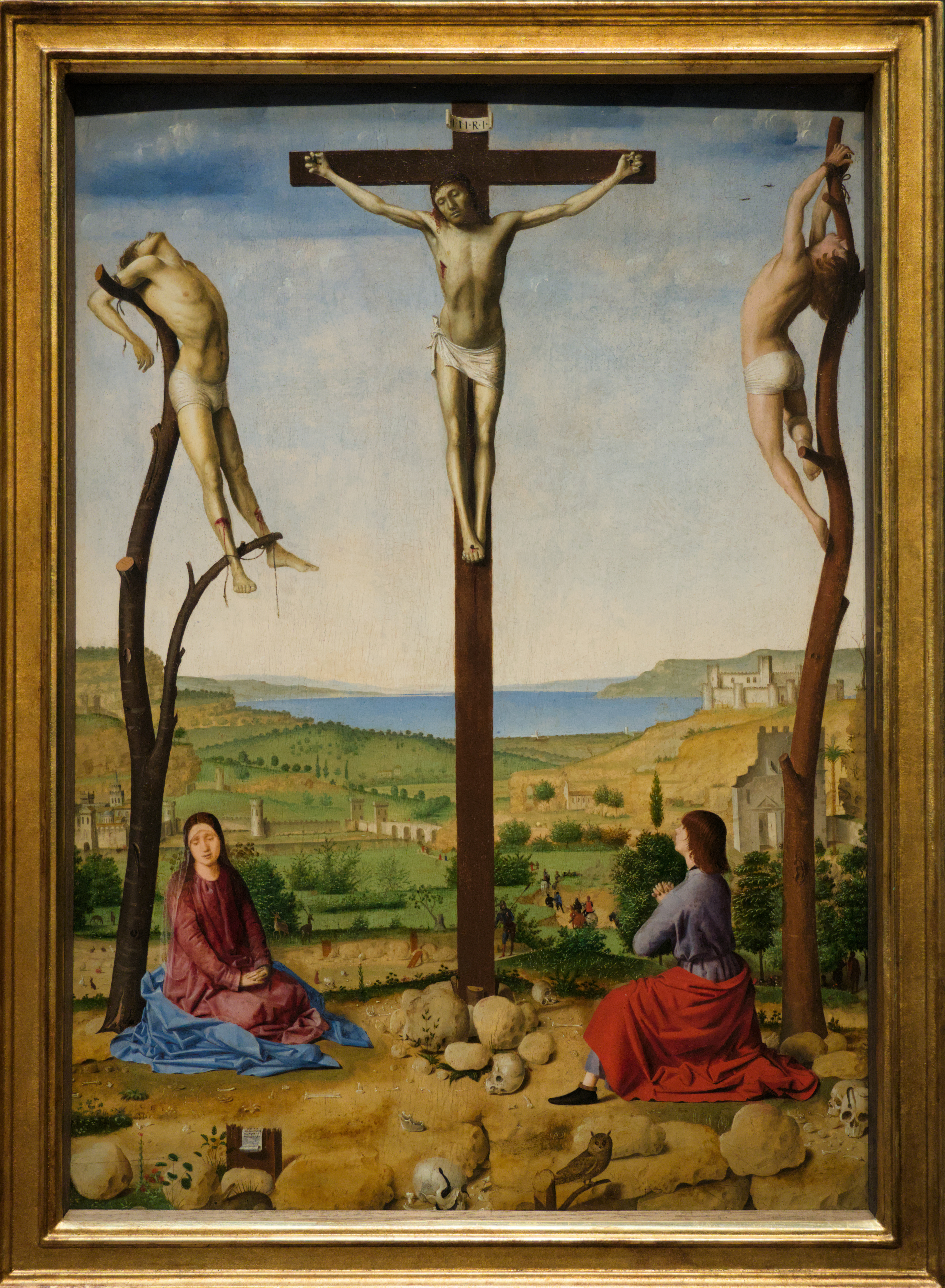

Calvary by Antonello da Messina (another version of which is at the National Gallery in London) also hangs in this gallery. While the crucified Christ seems at peace with his death, the other two on their crosses writhe in pain.

Compare these figures to contemporary Belgian artist Berlinde de Bruyckere’s Schmerzensmann (Man of Sorrows), on loan from the collection of David and Indré Roberts (see wide-view photo above). The piece consists of a wax and resin mold of a contorted human form, its skin stretched and broken, its legs wrapped around a tall rusty pole.

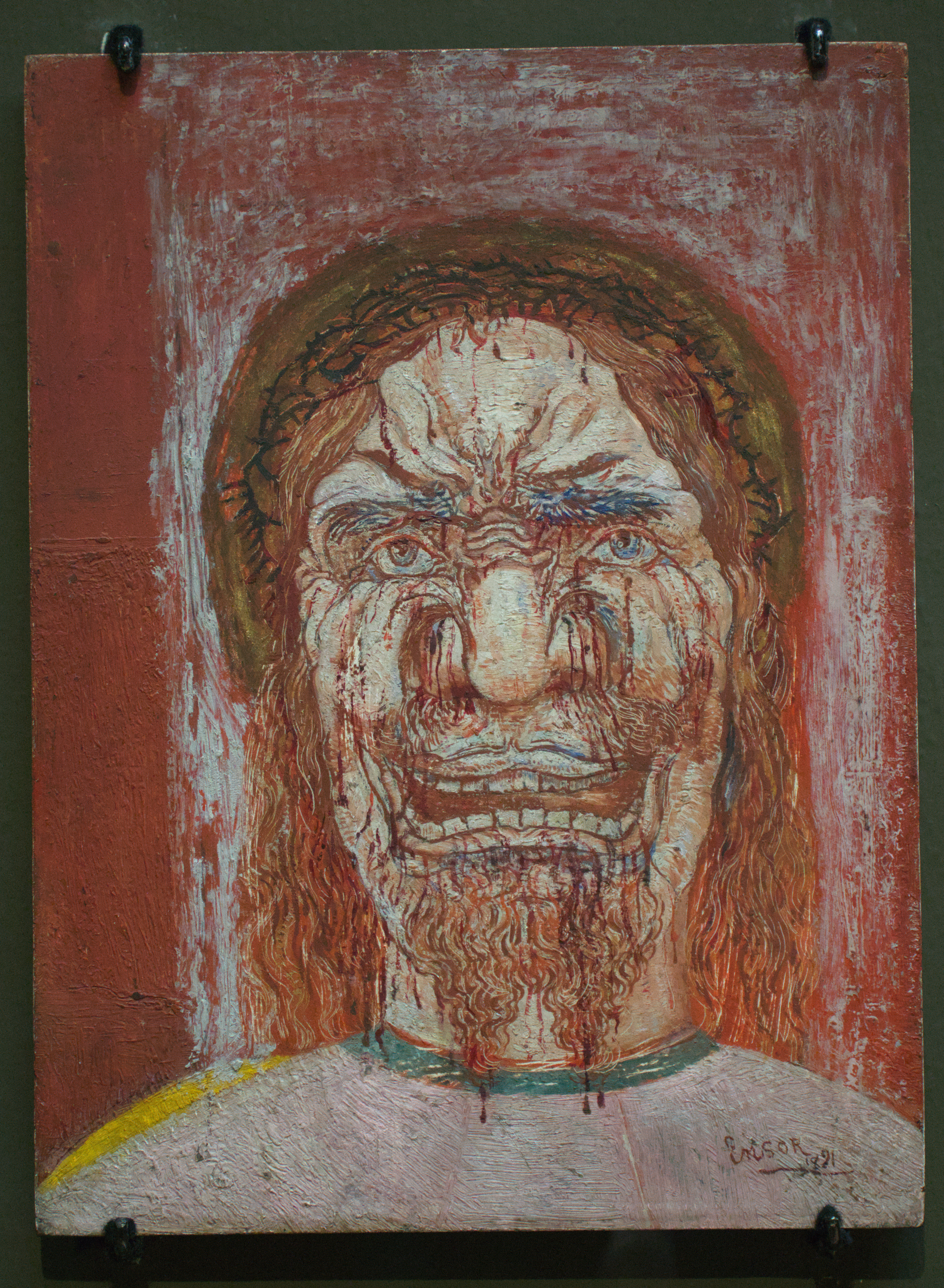

“Man of Sorrows” is also the title of an Early Netherlandish painting by Albrecht Bouts and a modern painting by James Ensor, which KMSKA displays side-by-side.

The earlier one is an incredibly moving image of pathos. Christ wears a thick, twisted, mock crown whose thorns dig holes into his forehead and draw blood. His eyes are red with tears and sunken in, and his lips are turning blue with the pallor of death. I find it quite beautiful, insofar as an image of suffering can be beautiful. (That’s a topic for another day.)

The Ensor painting, on the other hand, is decidedly not beautiful. In fact, I think it’s the ugliest image of Christ I’ve ever seen, with his crumpled face, scraggly hair, and bared teeth. There’s something very unsettling about his expression, and no wonder, as the curatorial text informs that Ensor drew inspiration from the masks of demon characters in Japanese theater. “His [Ensor’s] Jesus screams with rage about the injustice inflicted on him,” the label says. Is that what that expression is? To me he looks sinister. Like he’s growling at us. And I dislike his dinky crown that he wears like a headband; give me Bouts’s gnarly one instead.

I’m in favor of Christ images that show the rage he must have felt, but I don’t think Ensor is successful if that was his aim. To name a few modern artists who were: Guido Rocha (Tortured Christ, 1975) and David Mach (Die Harder, 2011), both of whom capture Jesus’s cry of dereliction on the cross.

The final themed gallery I’ll call out is “Heavens.”

The dominant Old Master work is a set of three panels from the upper tier of a colossal altarpiece that Hans Memling painted for the church at the Benedictine Abbey of Santa Maria la Real in Najera in northern Spain. All the other panels are lost.

The museum titles the central panel God the Father with Singing Angels—but I think the figure is more properly God the Son, Jesus Christ, portrayed as Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World). In his left hand he holds a cross-surmounted crystal globe, signifying his dominion over the earth, and with the other hand he gestures blessing. He wears a tiara and a red cope decorated with gold-thread embroidery, pearls, and precious stones, and his collar bears the words Agyos Otheos (Holy God).

Surrounding him is a musical band of angels, singing his praises from songbooks and, in the flanking panels, playing a variety of wind and string instruments: (from left to right) a psaltery, a tromba marina, a lute, a trumpet, a shawm, a straight trumpet, a looped trumpet, a portative organ, a harp, and a fiddle.

This ensemble probably evokes for you a particular sound—something like Tallis or Palestrina—soaring polyphonic vocals, a gentle yet majestic accompaniment. But instead, a different soundtrack played, audibly, in the room: songs from the 1967 debut album of the American rock band the Velvet Underground, several of which use religious language to describe the experience of doing drugs. “Heroin” opens like this:

I don’t know just where I’m going

But I’m gonna try for the kingdom, if I can

’Cause it makes me feel like I’m a man

When I put a spike into my veinAnd I’ll tell you things aren’t quite the same

When I’m rushing on my run

And I feel just like Jesus’ son

This aural element was complemented, on the gallery wall, by the guitar of Lou Reed, the band’s lead singer and songwriter. It’s signed by Andy Warhol, who produced and championed the Velvet Underground & Nico album and made its banana cover art, replicated on the instrument.

Adding to the mix, in the corner of the room was an installation by the Copenhagen-born and -based artist Olafur Eliasson, called Lighthouse Lamp. “Affixed to a tripod, a lamp situated within a Fresnel lens—a compact lens which was developed for lighthouses—emits a band of white light in 360 degrees,” the artist’s website explains. In this space, the beam takes on a triangular shape.

There was also an altarpiece of The Last Judgment and the Seven Acts of Mercy by Bernard van Orley, which references Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 25 about one’s entry into heaven being contingent on whether, in this life, you feed the hungry, give shelter to the homeless, visit the prisoner, and so on.

The “Heavens” gallery begs the question: How does one define “heaven”? Is it a physical place? A state of mind? An encounter? I think of related words like bliss, beatitude, communion, the sublime.

The celestial scene painted by Memling—and remember, it’s only partial, as the rest is missing—is beautifully rendered, but it also encapsulates what has become the popular cliché of heaven: angels on clouds, strumming harps, and a regal God swaying his scepter. Music-making, angelic beings, and the reign of God are all certainly a part of how the Bible describes heaven. But it’s also so much more. It’s a garden and a city. It’s healing and restoration. It’s the righting of wrongs. It’s all things made new. It’s jubilee. It’s a wedding—deep and lasting union between God and humanity. It’s an eternal interlocking of God’s space and ours (earth). It’s a global, transhistorical community of faith, gathered together around Christ their head, worshipping him in diverse languages, musical styles, dances, and other cultural expressions. It’s the culmination of the greatest story ever told.

Today, Memling’s vision of heaven probably fails to captivate most people, even Christians. So it’s an interesting experiment to compare it to how others conceive of the concept.

Eliasson’s Lighthouse Lamp wasn’t a commission on or explicit treatment of the theme, but the curator saw fit to place it beside Memling, because heaven is often conceived of as a light-filled space, and light can evoke the divine. For this reason, Memling painted his background gold. What’s more, the three-sidedness of Eliasson’s light beam may, for some, evoke the Trinity, the classical Christian doctrine of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost that Memling alludes to with the three precious stones on the fibula of Christ’s mantle.

Still, other folks experience what could be termed “heavenly” transcendence through the use of mind-altering substances, as did the members of the Velvet Underground, whose drug trips gave birth to their experimental music—which, in turn, has taken others to a transcendent place.

Whether in special exhibitions or displays of their permanent collections, I want to see more of this in museums: bringing old and new artworks into conversation with one another around universal themes, in the same room. (In some museums, the labels sometimes cross-reference works in other galleries, but that’s not the same.) Although there are benefits to the traditional approach of laying out art chronologically to give you discrete pictures of different historical eras and allow you to progress by time period, a thematic approach that compiles works from across time also has its benefits.

I’ve found cross-temporal art displays to be especially vitalizing, because instead of trying to tell history, they more naturally invite personal reflection and tend to be less academic in tone. Such an approach makes the art accessible to a larger number of people, especially those who don’t frequent museums. It helps us see the relevance of the Old Masters (or whatever the museum’s collection focus) for today—how the subjects they depicted often address topics or questions we still ask or wonder about or that reflect aspects of the common human experience, such as joy, suffering, family, death, betrayal, or festivity. Creating relationships between works made centuries apart, highlighting similarities and differences, can give us a broader perspective.

And for this museumgoer (pointing at myself) who is attracted to medieval and early Renaissance art and sometimes bypasses the contemporary galleries, the integrative approach is more engaging. Giving contemporary works a point of connection with the works I’m already inclined to like helps me enter into them more easily and fruitfully, and I’m more likely to spend time with them than if they were segregated.

New and old don’t have to be equally represented—Kolumba skews heavily contemporary, whereas KMSKA lets its strengths shine with the Old Masters, and yet the occasional unexpected intervention from years past or future always caused me to pause and be curious. Over the last several years I’ve been noticing other museums engaging in similar playful exchange—plopping a contemporary work into the medieval section, or vice versa, in a way that provides some kind of illumination.

This was my first and only visit to KMSKA, and as I understand, there’s not the same degree of intermixing of old and new year-round; this was a special exhibition that brought in contemporary works from outside, as the institution itself owns very few. But they did do something similar last year with the exhibition What’s the Story?, and the dangling light poems by Bernard Dewulf are a permanent fixture in the Old Masters galleries.

Have you been to a museum where works from different time periods were displayed side-by-side to create a discourse, and if so, did that choice enhance your engagement, insight, or appreciation? I’d love to hear what other museums are doing this!

This article took me some forty hours to write and to select and edit photos for. If you appreciate learning about my museum experiences and having access to high-resolution, downloadable art images, would you please consider adding to my “tip jar” (PayPal), or sponsoring a book from my Amazon wish list? Thank you!