“One of poetry’s great gifts is to slow us down,” writes Peggy Rosenthal in Praying the Gospels through Poetry. “We’re used to racing ahead as we read, whether it’s a newspaper or an email memo or even an essay: language in these forms propels us forward, urging us to grab up its main points. But poetry doesn’t press ahead so much as hold us still—in the wonder of words crafted to open into another dimension.”

Below are twenty-five poems to “hold us still” this holiday season.

I’ve collected hundreds of Advent and Christmas poems over the past decade, but for this feature one of the selection criteria was that the poem must be freely available online. I chose the number twenty-five because that is standard in most Advent calendars—tools for counting down the days to Christmas. This way, you can choose, if you wish, to bookmark this page and read just one poem a day from December 1 to 25, each one a little treat.

The order progresses, in general, from Advent longing and anticipation to Christmas joy and wonder to post-nativity moments like the presentation in the temple and the visit of the magi.

For previous years’ installments, see volume 1, volume 2, and volume 3.

1. “Advent Madrigal” by Lisa Russ Spaar: I’m not sure I understand this poem, but I like it. A madrigal is a part-song, and this is a song of waiting in simultaneous belief and doubt, of being irresistibly attracted to God’s story while also skeptical of aspects. The speaker compares the moon to a flashlight that a theater usher shines down the aisle to escort folks to their seats. What does it mean that “the treetops sough // & seize with” escape? Escape from what? And that the earth has been purloined? I don’t know, but the final couplet really lands for me—about how in the dark night of our not-knowing, we make our Advent wreaths, decking them with evergreens, their round shape an O of lament and awe before the yet-to-be-seen.

Source: University of Virginia Office of Engagement

2. “Prayer” by John Frederick Nims: The first in a sequence of five poems, “Prayer” expresses a sense of emptiness and desire, beckoning an unnamed one whom I read as Christ to come and fill. “Come to us, conceiver, / You who are all things, held and holder. / . . . / Come, infinite answer to our infinite want.”

Source: Five Young American Poets, vol. 3 (New Directions, 1944); compiled in The Powers of Heaven and Earth: New and Selected Poems (Louisiana State University Press, 2022)

3. “how he is coming then” by Lucille Clifton: This poem is part of a sequence on the life of Mary; it appears between “mary’s dream” (on the Annunciation) and “holy night” (on Mary’s ecstatic birthing experience). In answer to the title, Clifton gives three similes.

Source: Two-Headed Woman (University of Massachusetts Press, 1980); compiled in The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton (BOA Editions, 2012)

4. “Advent 2” by Anna A. Friedrich: This poem is the second in a series of Advent villanelles commissioned by the poet’s church in Boston last year to converse with one or more of the lectionary readings for each week of the season. Malachi 3:1–4 is the primary touchstone here, a formidable prophetic passage that compares God in the day of his coming to a blazing fire that refines metal. Stanza 3 references the fiery repentance-preaching of John the Baptist from Luke 3:1–6, and then Friedrich draws in another, unexpected “fire” text: Daniel 3, in which three young Hebrew men are thrown into a furnace by a Babylonian king for their refusal to worship his gods but are preserved from harm when a mysterious fourth person appears with them in the flames. Friedrich connects this story to the promise that the earth and its inhabitants will not be wholly consumed in the fire of God’s judgment—only the impurities, the dross, will be destroyed, so that all may be restored to their truest selves. Hence why, in Friedrich’s words, “We pray for His fire. We trust this flame.”

Source: Monafolkspeak, December 11, 2024 | https://annaafriedrich.substack.com/

5. “Desert Blossoming” by Amit Majmudar: A reflection on the messianic promise of Isaiah 35:1–2, this poem celebrates how, through the deserts of Israel, Jesus “scattered his verses on the secretly gravid ground,” causing the wilderness to blossom. Majmudar mentions red, the color of fire (an image he connects to the light of faith), rhyming it with “bled.” Although he uses this final word in the sense of spreading into or through—oases bleeding into one another as dry land becomes water—one can’t help but think of Jesus’s sacrificial death, his blood extraordinarily fertile, producing life.

Source: Heaven and Earth (Story Line, 2011) | http://www.amitmajmudar.com/

6. “Name One Thing New” by Seth Wieck: This six-line poem takes the Teacher of Ecclesiastes to task, responding to his cynical claim that “there is nothing new under the sun” (Eccles. 1:9) with a counterexample.

Source: Ekstasis, December 6, 2021 | https://www.sethwieck.com/

7. “For My Mother at Advent” by Brian Volck: The poet recalls a simple Advent tradition his mother established in his childhood and reflects on her spiritual legacy, her lifetime of Christ-inspired kindnesses that continue to pillow him. How might we soften the hardness of the world for others?

Source: Flesh Becomes Word (Dos Madres, 2013) | https://brianvolck.com/

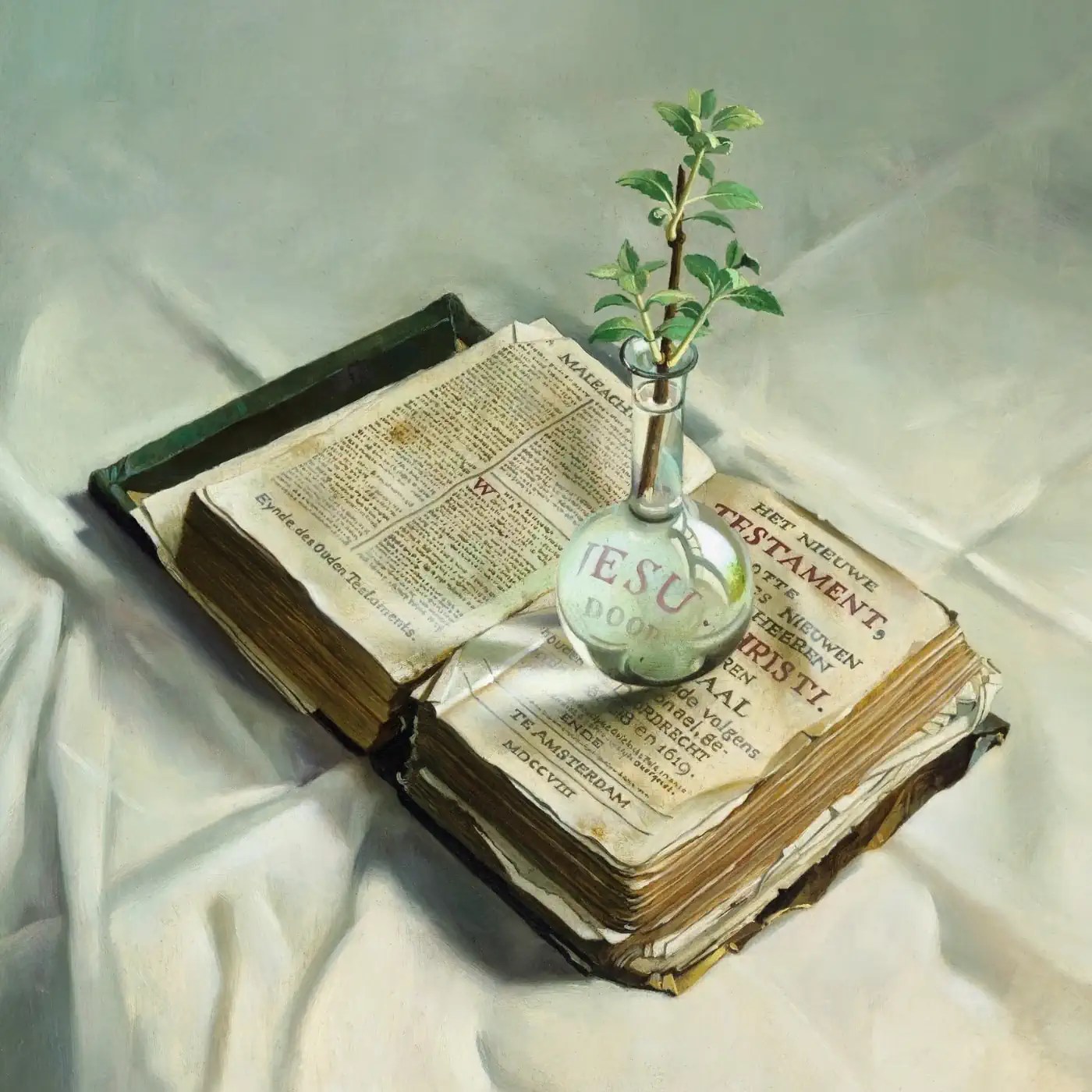

8. “Advent” by Suzanne Underwood Rhodes: This stunning poem makes unlikely intertextual connections, bringing Matthew 19:24 (one of Jesus’s hard sayings regarding wealth) to bear on John 1. Its unique angle on the Incarnation and its evocative imagery have inspired an experimental jazz composition and several paintings.

Source: What a Light Thing, This Stone (Sow’s Ear, 1999) | https://www.suzanneunderwoodrhodes.com/

9. “An Hymn to Humanity” by Phillis Wheatley: “Lo! for this dark terrestrial ball / Forsakes his azure-pavèd hall / A prince of heav’nly birth!” So begins this poem on the Incarnation by Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753–1784), the first African American to publish a book of poetry. In stanzas 2 and 3, God the Father dispatches the Son to establish his throne on earth, “enlarg[ing] the close contracted mind, / And fill[ing] it with thy fire.” The “languid muse” in stanza 5 refers to Wheatley herself, whereas the “celestial nine” are the ancient Greek inspirational goddesses of literature, science, and the arts. The “smiling Graces” is another classical reference.

Source: Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London, 1773). Public Domain.

10. “In My Hand” by Sarah Robsdottir: Mary remembers the moment she conceived Jesus, one ordinary day when sitting down to a bowl of lentil stew.

Source: Aleteia, April 9, 2018

11. “The Risk of Birth, Christmas, 1973” by Madeleine L’Engle: Best known for her children’s novel A Wrinkle in Time, Madeleine L’Engle was also a poet. Here she compares our era to the one in which Jesus was born—both are characterized by violence and hate, and yet Jesus, the embodiment of divine love, willingly entered the peril.

Source: The Weather of the Heart (Doubleday, 1978); compiled in The Ordering of Love (Crosswicks, 2005) | https://www.madeleinelengle.com/

12. “On Another’s Sorrow” by William Blake: Through the Incarnation, God lovingly, humanly, entered the world of human woe to experience it firsthand. “He doth give His joy to all,” Blake writes: “He becomes an infant small, / He becomes a man of woe, / He doth feel the sorrow too.” I featured this poem about Emmanuel, God-with-us, in a musical setting by singer-songwriter David Benjamin Blower in 2023 but was surprised that Blower omitted Blake’s final stanza, whose closing couplet I find striking, as it conveys Jesus’s continued identification with and compassion for humanity, how he moans alongside us in our suffering. For a different musical interpretation, also in an acoustic indie folk mode, see the one by Portland-based artist Michael Blake, from his 2021 album Songs of Innocence and Experience:

Source: Songs of Innocence and Experience (London, 1794). Public Domain.

13. “Missing the Goat” by Lorna Goodison: An immigrant from Kingston, Jamaica, to Toronto, Ontario, Goodison writes of the heightened feeling of exile but also of creative adaptations during the holidays as she tries to carry out the food traditions of her native country on a foreign soil where some of the ingredients are in more limited supply. For the sorrel wine, traditionally made with roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) petals, tropically grown, she has to make do with redbuds. And the local shops have run out of goat meat—“the host of yardies” (people of Jamaican origin) who’ve moved to the area have already bought it all up—so “we’ll feast then on curried some-other-flesh.” Despite the differences from home, Christmas is still Christmas, and she raises her “hybridized wassail cup” to her new place, her new neighbors (many of them, like her, also recent arrivals from the Caribbean), and the creation of new rituals in multicultural Toronto.

Source: Controlling the Silver (University of Illinois Press, 2010); compiled in Collected Poems (Carcanet, 2017)

14. “Word Made Flesh” by Kathleen Raine: Awarded the CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) for her significant contributions to literature and culture, Raine has been described as a mystical and visionary poet. Here is her revoicing of John 1. What a powerful last two lines!

Source: The Pythoness (Hamish Hamilton, 1949); compiled in The Collected Poems of Kathleen Raine (Golgonooza, 2000)

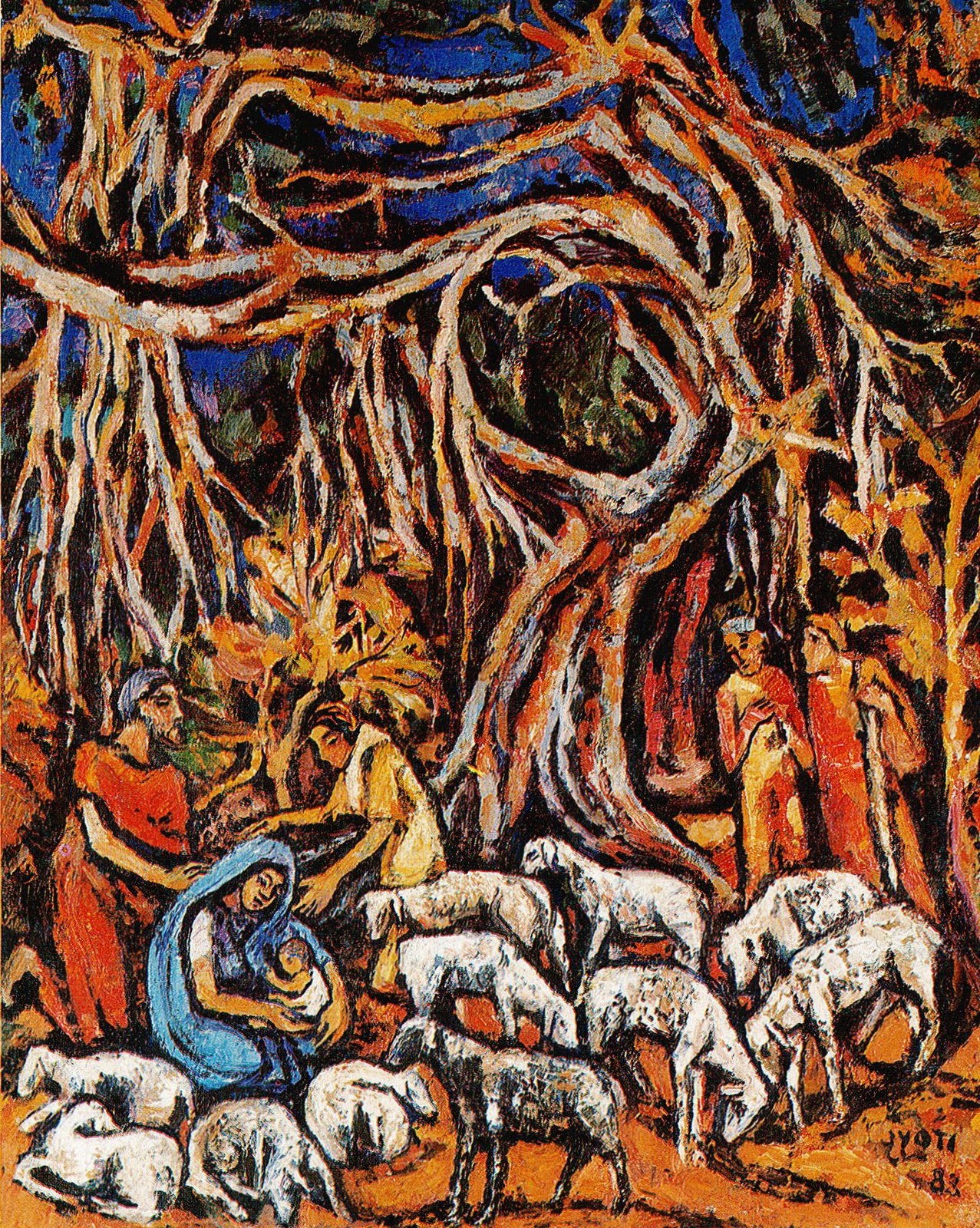

15. “Nativity” by Barbara Crooker: In the heavy dark, in the windy cold, “love is born in the world again” every December when we retell the story of Christ’s birth.

Source: Small Rain (Purple Flag, 2014) | https://www.barbaracrooker.com/

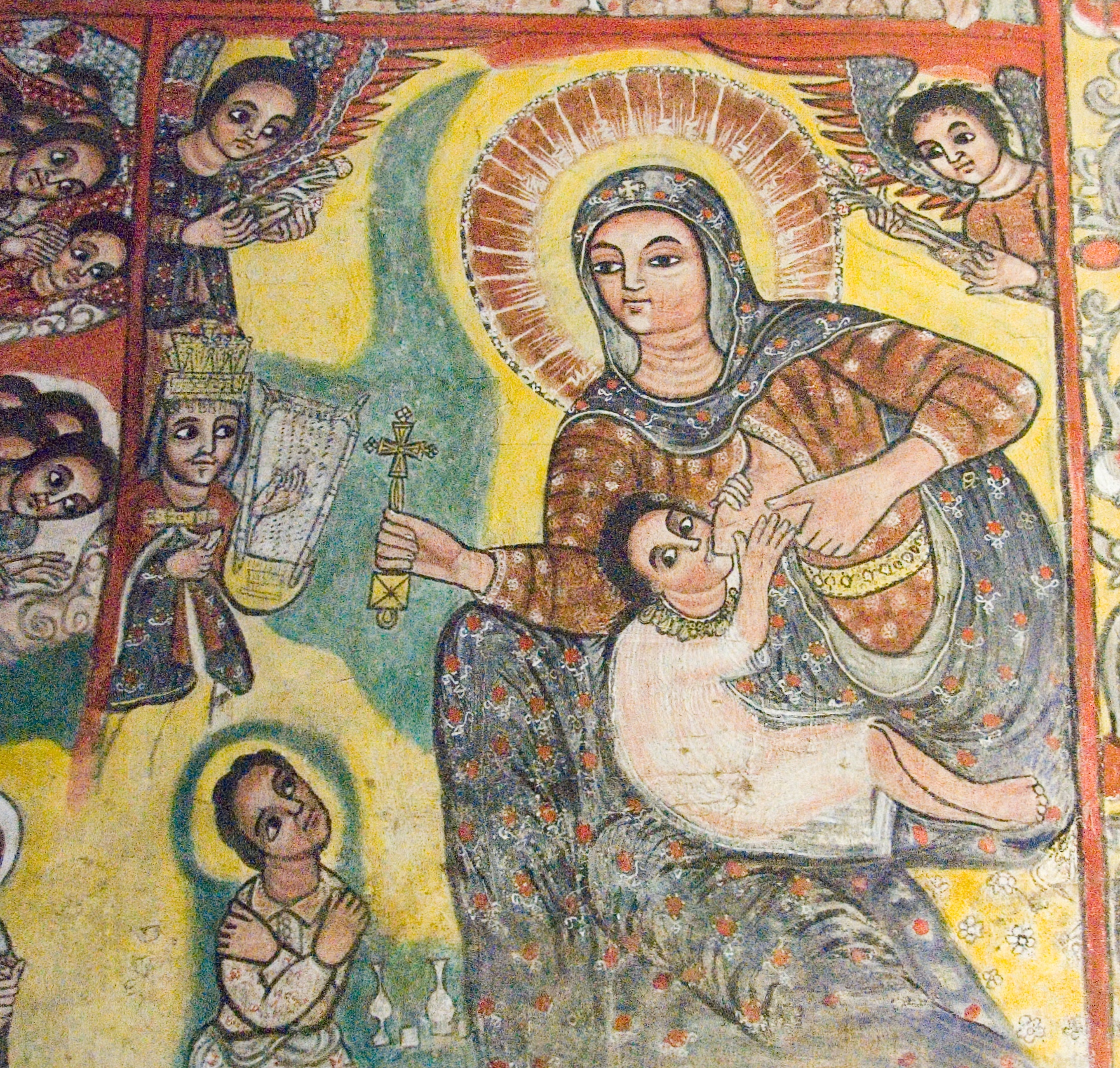

16. “First Miracle” by A. E. Stallings: The first miracle Jesus performed, according to the Gospel of John, was turning water into wine. Stallings reflects on an earlier miracle performed by his mother’s body, and all birth-giving mothers’: turning nutrients from her blood into milk.

Source: Like: Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018)

17. “What Sweeter Music Can We Bring” (or “A Christmas Carol, sung to the King in the Presence at Whitehall”) by Robert Herrick: “The Darling of the world is come”! Originally written as a song for soloists (each number corresponds to a different singer) and chorus, this poem reverses the typical seasonal imagery of Christmas, remarking how, at Jesus’s birth, “chilling Winter’s morn / Smile[s] like a field beset with corn” and “all the patient ground [is turned] to flowers.” The original music by Henry Lawes is lost, but many contemporary composers have written settings of the text, most famously John Rutter.

Source: Hesperides: Or, Works Both Human and Divine (London, 1648). Public Domain.

18. “Sharon’s Christmas Prayer” by John Shea: A five-year-old recounts the Christmas story, and when she reaches the clincher, she can’t hold back her glee.

Source: The Hour of the Unexpected (Argus Communications, 1977); also in Seeing Haloes: Christmas Poems to Open the Heart (Liturgical Press, 2017)

19. “God” by D. A. Cooper: Riffing on Williams Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow,” this spare poem attends to the birth and death of the incarnate God, upon which so much depends.

Source: Reformed Journal, September 3, 2024

20. “Lullaby after Christmas” by Vassar Miller: The speaker wishes sweet sleep for the newborn Christ child, wishes to keep him innocent of his fate for as long as possible—for “even God has right to / Peace before His pain.” Consisting of four sestets whose second, fourth, and sixth lines rhyme, the poem has a sing-songy quality that is jarring for the juxtaposition of words like “soft,” “warm,” and “tinkling” with the likes of “blood,” “gore,” and “die.”

Source: Onions and Roses (Wesleyan University Press, 1968); compiled in If I Had Wheels or Love: Collected Poems of Vassar Miller (Southern Methodist University Press, 1991)

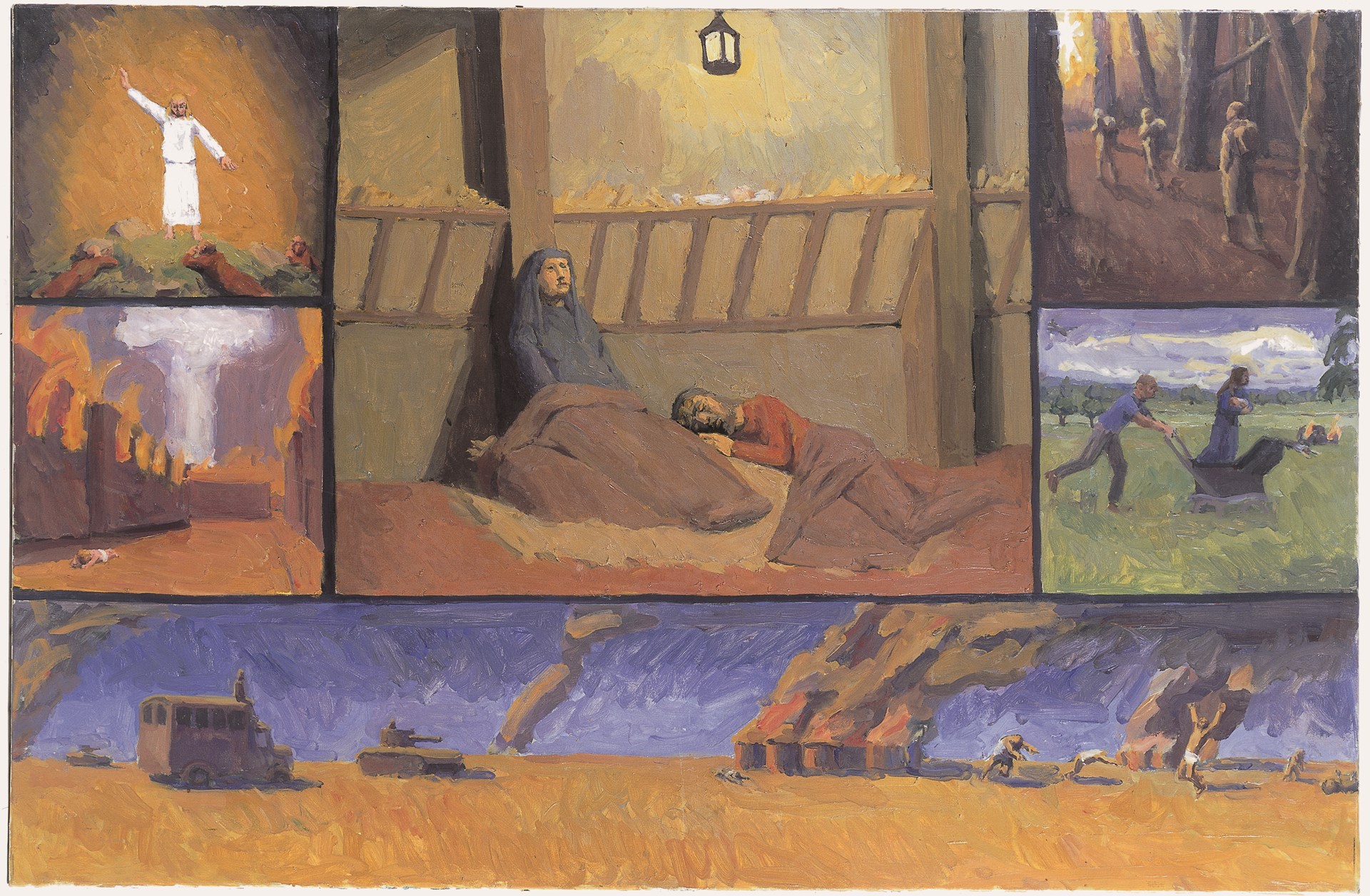

21. “Journey of the Magi” by T. S. Eliot: Eliot wrote this poem shortly after his conversion to Christianity in 1927. Opening with a passage from a Christmas sermon by the seventeenth-century Anglican bishop Lancelot Andrewes, it is from the perspective of one of the magi, who made a long, toilsome journey in search of the meaning of a mysterious guiding star. After the magi’s encounter with the Christ child, they would never be the same; their paganism would no longer satisfy. The poem is about the transformative impact Christ has on those with humility enough to see him for who he is (having followed the light of revelation) and to worship him accordingly. And that transformation is in some ways painful, as it involves giving up some of the things one once held dear.

“Were we led all that way for / Birth or Death?” the magus asks. Jesus’s wasn’t the only birth they witnessed; they, too, were (re)born in Bethlehem. But spiritual rebirth is also a sort of death—the magi died to their old selves and false loves and loyalties. Thus, when they returned to Babylon, they felt like strangers in a strange land. They were now citizens of a different kingdom, and filled with a longing for its consummation.

Source: Journey of the Magi (Ariel Poems) (Faber & Gwyer, 1927). Public Domain.

22. “Twelfth Night” by Sally Thomas: (Scroll to second poem.) As the Christmas season draws to a close, holly berries shrivel and drop, the “candles drown themselves in waxen lakes,” “the tree’s a staring corpse,” and a spider has built a web across the mantel nativity. Thomas uses the passing of the season to reflect more broadly on the passing of time and our own dustiness and desiccation—and by contrast, the unchangeability of God.

Source: Pulsebeat Poetry Journal no. 2 (May 2022) | http://www.sally-thomas.com/

23. Untitled poem by S. E. Reid: Most reflections on the New Year are full of enthusiastic goal-setting and go-getting, but Reid, gardening in her greenhouse in the crisp cold of January, describes a “fall[ing] backwards,” “dropping into the dark,” “shivering,” herself a seed, latent in the soil, trusting God that growth will come.

Source: The Wildroot Parables, January 8, 2024 | https://sereid.substack.com/

24. “Anna the Prophetess” by Tania Runyan: Forty days after Jesus’s birth, Mary and Joseph presented him in the Jerusalem temple. Runyan imagines this event from the perspective of Anna, a woman who was widowed young and thenceforth lived at the temple into old age, devoted to prayer, fasting, praise, and prophecy.

Source: Simple Weight (FutureCycle, 2010) | https://taniarunyan.com/

25. “The Work of Christmas” by Howard Thurman: Drawing on Jesus’s mission statement in Luke 4, the great African American theologian and civil rights leader Howard Thurman urges us to continue the work of Christmas—finding, healing, feeding, etc.—throughout the year. Listen to the simple yet vigorous choral setting by Elizabeth Alexander.

Source: The Mood of Christmas and Other Celebrations (Friends United, 1985)