SPOTIFY PLAYLIST: September 2023 (Art & Theology): Another monthly gathering of good, true, and beautiful music of a spiritual bent from a variety of sources, ranging from a Victorian lullaby to a hymn revamp by Ike and Tina Turner to a traditional Yom Kippur melodic motif reimagined to a bluesy saxophone prayer to an old-time song about Noah from the southern US to a Christian praise song sung by a Miskito church community in their native tongue. Two selections from the playlist are below.

>> “Abodah” by Ernest Bloch, performed by Sheku Kanneh-Mason: Ernest Bloch was a Swiss-born American composer who drew heavily on his Jewish heritage in his work. Abodah (עֲבוֹדָה) (more commonly transliterated avodah) is Hebrew for “service,” “work,” or “worship,” a word often used in relation to the ritual service that used to be performed by the Jewish high priest in Jerusalem each year on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), before the temple was destroyed; described in Leviticus 16, it involved confession of sin and animal sacrifices.

“May the offering of our lips be accepted as a replacement for the sacrifice of bulls,” the rabbis now say—and thus present-day Yom Kippur liturgies feature poetic recitations from Leviticus 16 and related Mishnah texts, “an expression of the Jewish people’s yearning both for spiritual liberation and redemption,” writes Neil W. Levin. More conservative congregations will vocalize prayers for a rebuilding of the temple and the restoration of sacrificial worship. But for an example of a seder avodah from the Reform tradition, see here. Yom Kippur is celebrated on September 24–25 this year.

Bloch’s Abodah composition is based on a tune, part of a canon of tunes known as the missinai (lit. “from Sinai”), that originated in the Ashkenazi communities of medieval Germany and that is still used today in Ashkenazi synagogues on Yom Kippur. Bloch composed the piece for piano and violin, but it’s arranged here for solo cello and performed by the internationally acclaimed Sheku Kanneh-Mason [previously].

For Christians, the atonement rituals from Leviticus find their fulfillment in the once-for-all self-sacrifice of Jesus, and though this solemn tune has its roots in the Jewish faith tradition, its meditation on human sin and divine forgiveness can cross religious boundaries.

>> “I’ll Fly Away” (Yo volaré) from We the Animals: This spare, a cappella performance of a 1929 southern gospel song by Albert E. Brumley plays during the opening credits of the film We the Animals (2018), sung by Josiah Gabriel, one of the three main child actors. I’m interested in how and why religious songs are employed in nonreligious films, and this one was really effective in establishing not only the tone of the movie but also its theme of freedom.

Based on a semiautobiographical novel of the same name by Justin Torres, We the Animals follows three Puerto Rican brothers ages seven and up navigating a volatile family life in rural upstate New York. There’s violence and tenderness, depression and joy, and I appreciate its exploration of complicated masculinity, and how nuanced the character of the father is. (Torres has said that the process of writing the book was partly about finding empathy for his father who was abusive, and that the story is really about love and grace in a family.) In the film, flying is used as a visual metaphor for the youngest son’s, the narrator’s, rising above captivity (mainly psychological) and coming to a place of existential flourishing. The film is excellent, as is the book, though beware the R rating. Streaming on Netflix and Hulu.

+++

UPCOMING CONCERT: “Beyond Measure: An Evening of Music in Celebration of Abundantly More,” dir. Jeremy Begbie, September 8, 2023, Duke Divinity School, Durham, NC: To celebrate the release of Dr. Jeremy Begbie’s book Abundantly More: The Theological Promise of the Arts in a Reductionist World, Duke Initiatives in Theology and the Arts is presenting a special concert with the New Caritas Orchestra, conducted by Begbie. It will take place next Friday at 7:30 p.m. at Goodson Chapel on the campus of Duke Divinity School, and no tickets or registration are required. The program will explore the power of music—along with words and images—to expand our theological imagination, and it will be followed by a reception and book signing.

I suspect it will be similar in format to Begbie’s “Home, Away, and Home Again: The Rhythm of the Gospel in Music” event, which I attended in 2017 and was wonderful. (View the video recording below.) In his lecture-concerts, Begbie interweaves composer biography, musical analysis, theological commentary, storytelling, and performance to help audiences truly hear and appreciate the music. In “Home, Away, and Home Again,” he discusses the technical term “tonic” (the note upon which all other notes of a piece of music are hierarchically referenced, the one that gives the piece its sense of stability), demonstrating with various examples how 90 percent of Western music starts at home, goes places, then arrives back home but changed. Along the way he discusses themes of war, despotism, (up)rootedness, loss, hope, the resurrection, and new creation. Featured composers include Béla Bartók, Antonín Dvořák, Aaron Copland, Ennio Morricone, Leonard Cohen, and Benny Goodman.

+++

UPCOMING CONFERENCE: “Poets of Presence: Faith, Form, and Forging Community,” October 27–28, 2023, Loyola University, Chicago: Sponsored by Presence: A Journal of Catholic Poetry and The Francis and Ann Curran Center for American Catholic Studies at Fordham University, this poetry conference will feature the keynotes “The Art of Faith and the Faith of Art” by Christian Wiman and “The Forge and the Fire: God in the Blacksmith Shop” by Angela Alaimo O’Donnell. There will be workshops on writing formal poetry, translating poetry, and an editor’s secrets for successful submissions, among others, and poetry readings. I was excited to see Paul J. Pastor [previously] on the list of presenters! Cost: $60.

+++

DOCUMENTARY: Many Beautiful Things: The Life and Vision of Lilias Trotter, dir. Laura Waters Hinson (2015): Available for free on YouTube, this seventy-minute documentary shines a light on Lilias Trotter (1853–1928), an English painter and protégé of the leading Victorian tastemaker John Ruskin who, instead of pursuing an art career as Ruskin had urged her to do, became a Christian missionary in Algiers for forty years—as a single woman, self-funded (all the missions agencies rejected her because she had a heart condition that made her physically vulnerable). Her ministry centered on the women in the kasbah—teaching them to read, helping them attain economic independence. She also befriended a Sufi brotherhood whose members were eager to hear her talk about God. In Many Beautiful Things, Michelle Dockery of Downton Abbey voices words from Trotter’s books, journals, and correspondence, and art director Austin Daniel Blasingame has deliciously animated her art! (See behind the scenes of that process.) Sleeping at Last supplied the original soundtrack.

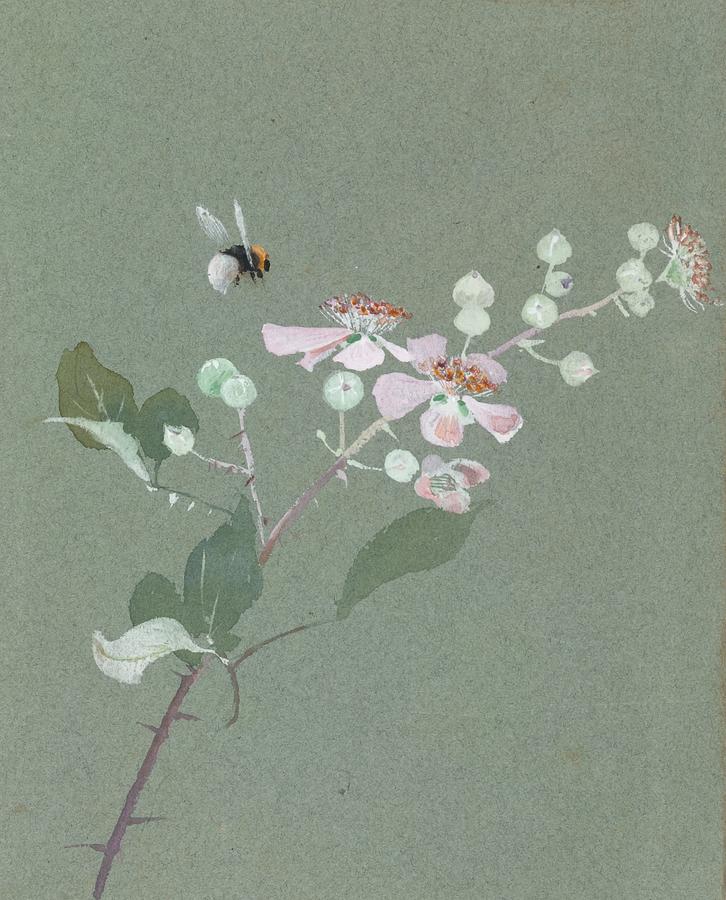

While in North Africa, Trotter continued making sketches and watercolors, documenting the everyday life that surrounded her—people, bees, flowers, sunsets. These are minor works/studies, not intended for the art market, but they were for Trotter a major way of delighting in God’s creation. I don’t like how the marketing of the film leans heavily into the narrative of “Oh, look at Lilias, so selfless and heroic, sacrificing artistic fame for service, she really could have been tops if she hadn’t given it up,” as it wrongly suggests that evangelistic or nonprofit work is more God-honoring than art making, or that recognition in one’s field is not something a Christian should desire. The film itself mostly avoids that way of looking at it, focusing instead on Trotter’s faithfulness in responding to a call that was particular to her and then finding ways to integrate art, as an avocation, into her new life in Algiers. “Her art . . . wasn’t lost in Algeria. If anything, it was fed,” says biographer Miriam Rockness. As viewers, we’re asked to reexamine our conception of success.

I had never heard of Lilias Trotter before watching this documentary (thanks for the recommendation, Sarah!), but now I’m glad to know about her. Learn more at https://liliastrotter.com/, and follow the Lilias Trotter Legacy on Instagram, Facebook, and/or Twitter. Also, the current issue of Christian History magazine (no. 148) is devoted entirely to Trotter; you can download a free copy (or purchase a physical one) here.