SPOTIFY PLAYLIST: September 2024 (Art & Theology)

+++

NEW ALBUMS:

>> Live On by the Good Shepherd Collective: The fourteen songs on this seventh full-length album by the Good Shepherd Collective are a mix of gospel, pop, and indie covers (Natalie Bergman, Harry Connick Jr., Aaron Frazer, Joni Mitchell, the Alabama Shakes, Celine Dion, Valerie June, Toulouse, Wilder Adkins) and two originals. Here’s “Look Who I Found” by Harry Connick Jr., sung by Charles Jones, followed by “Peace in the Middle” by Dee Wilson, Asaph Alexander Ward, and David Gungor, sung by Wilson, Gungor, and Rebecca McCartney. For more video recordings of songs from the album, see the Good Shepherd New York YouTube channel, which also features weekly digital worship services. Released July 12.

>> Facing Eden by Hope Newman Kemp: I heard Kemp perform at last year’s Square Halo conference and was compelled by her style, spirit, and songwriting. So I’m excited to see that several of the songs she shared live have now been recorded and released on her brand-new album! Produced by Jeremy Casella and tracked with a session band at the storied Watershed Studio in Nashville, Facing Eden leans toward café jazz but also bears influences from the Jesus Folk music of the 1960s that she was immersed in growing up. “Encompassing expansive sonic territory, the record isn’t afraid to wander into blue cocktail hours (‘My Inflatable Heart’), gospel riversides (‘Mercy,’ ‘Come Home,’ ‘Let It Rise’), ballad-style acoustic hymnody (‘Maria’s Song’), and even the free rubato motion of a musical theatre sound (‘Take Them Home’).” Released August 30.

+++

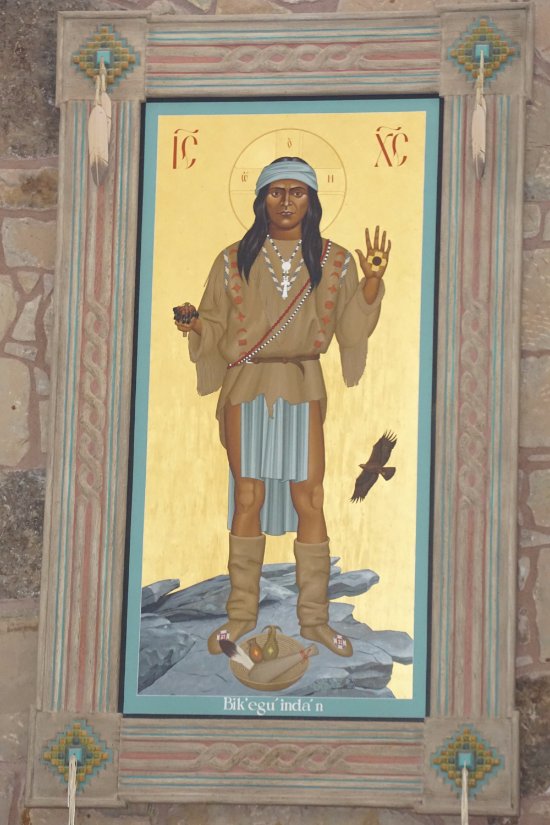

ARTICLE: “Apache Christ icon controversy sparks debate over Indigenous Catholic faith practices” by Deepa Barath, Associated Press: In 1989, a new icon by the Franciscan artist-friar Robert Lentz was installed behind the altar of St. Joseph Apache Mission church in Mescalero, New Mexico. According to the artist’s statement, the painting shows Christ as a Mescalero holy man, standing on the sacred Sierra Blanca (White Mountains). A sun symbol is painted on his left palm, and in his right hand he holds a deer hoof rattle. A basket at his feet holds an eagle feather, a grass brush, and bags of tobacco and cattail pollen, items used in Native rituals. Behind him flies an eagle, the guide who led the nomadic hunter-gatherer Apaches to their “promised land” of the Tularosa Basin in southern New Mexico some seven hundred years ago. The inscription at the bottom reads, “Bik’egu’inda’n,” Apache for “Giver of Life.” The Greek letters in the upper corners are an abbreviation for “Jesus Christ.”

Fr. Dave Mercer, a former priest at St. Joseph’s, describes the image and its significance:

When Franciscan Br. Robert Lentz painted his Apache Christ icon, he did so with great care for Apache traditions and sacred customs and with dialogue with tribal spiritual leaders, the medicine men and women. With their approval, he painted Jesus as a medicine man, including symbols and sacred items for which our Apache friends needed no explanation. They understood the message that our Lord Jesus had been with them all along and that he is one of them as he is one with the people of every land.

But on June 26, the church’s then-priest, Father Peter Chudy Sixtus Simeon-Aguinam, who had been installed in December 2023, removed the icon and a smaller painting depicting a sacred Indigenous dancer. Also taken were ceramic chalices and baskets given by the Pueblo community for use during the Eucharist. Neither Father Chudy nor the Diocese of Las Cruces, which oversees the mission, have provided a statement, but in July Father Chudy departed and, due to the demands of the congregation, the icon and other objects were returned. Presumably the removal was due to a fear of syncretism.

I’m not able to address that complicated charge in this roundup format, but I wanted to put this news item out there to show how art so often shapes religious communities—in this case affirming the Apache Christian identity (contrary to the claims of some, the two are not mutually exclusive) and conveying a sense of God-with-us and God-for-us. Click here to watch a five-minute video interview with the artist from 2016, who says the icon of the Apache Christ is an effort to heal the wounds that Christian missionaries inflicted on Native people in the past.

+++

NEW BOOK: The Bible in Photography: Index, Icon, Tableau, Vision by Sheona Beaumont: Artist and scholar Sheona Beaumont [previously] is a visiting research fellow at King’s College London and cofounder of Visual Theology. In this book published by T&T Clark, she discusses, with critical depth, a range of “photographs that depict or refer to biblical subject matter, asking how the reception of the Bible by photographers and their audiences reveals their imaginative interpretation,” she writes. “I hope to show that, far from being an outdated, idiosyncratic or dead referent, the Bible’s many afterlives in photographs are uniquely qualified to show up the workings of a modern religious imagination” (1).

In preparation for this project, Beaumont comprehensively scoped the representations of biblical characters, scenes, and texts through the whole of photographic history, from Fred Holland Day and Julia Margaret Cameron to Gilbert & George and Bettina Rheims. For the book she chose fifty-five such images and interviewed twenty living photographers. In addition to fine-art photography, she covers documentary photography, advertising photography, propaganda, diableries, and spirit photography.

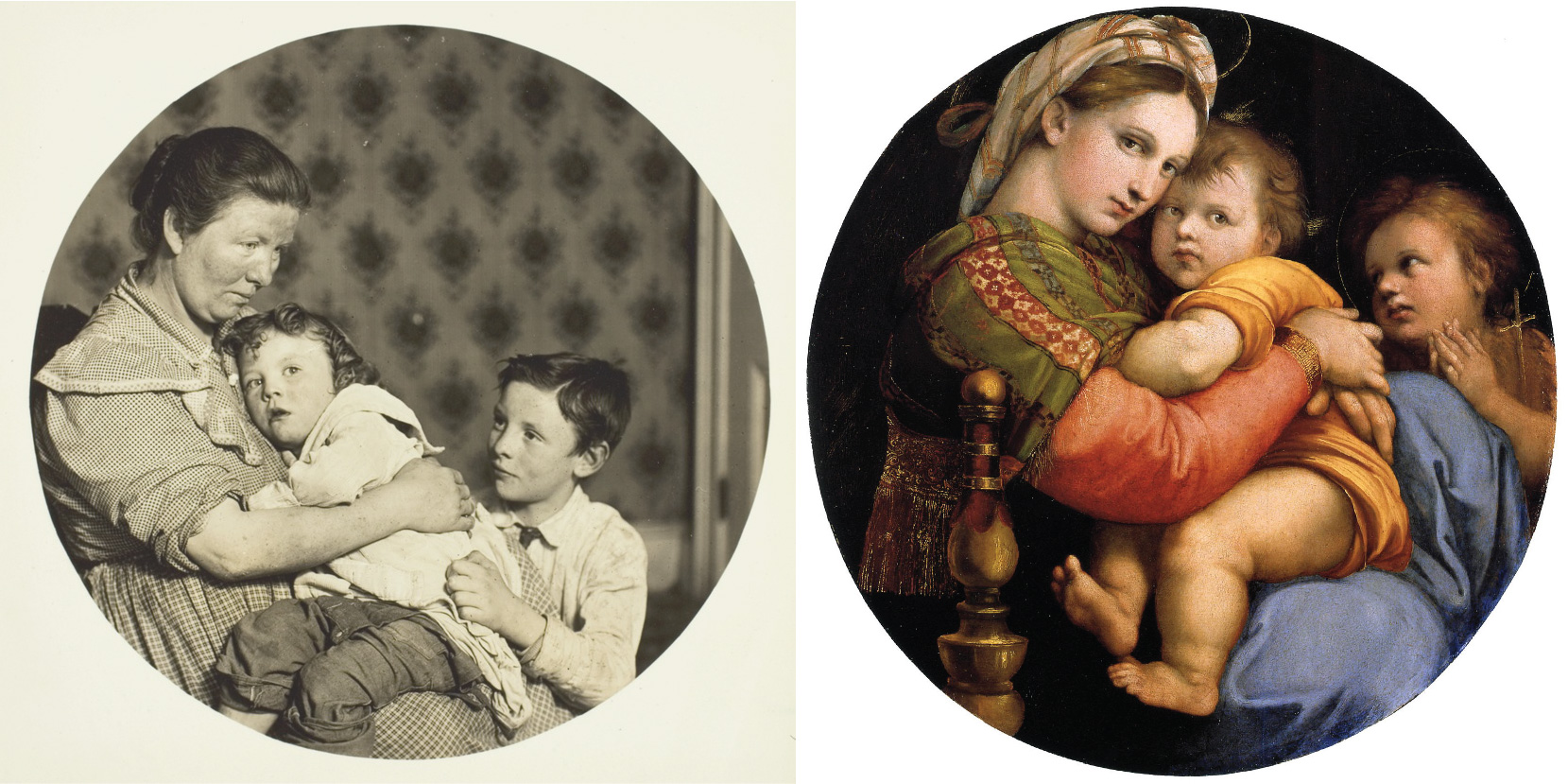

The Bible in Photography is highly academic; nonscholars will probably find part 1, where the author establishes the conceptional and methodological footing for her inquiry, too dense (it’s in dialogue with Hans-Georg Gadamer, Marshall McLuhan, Walter Benjamin, and Anthony Thiselton). For me, the highlight of the book is the selection of images and the grappling with the literal and the spiritual—the difficulties of representing historically real persons using contemporary models, and of conveying a “something more” beyond the surface, an element of transcendence. Some of the photographic pieces I’ve never encountered before, such as Corita Kent’s arrangement of journalistic photographs as Stations of the Cross from the Spring 1966 issue of Living Light. There’s much to savor here!

My research interests center on the figure of Christ, a figure that, Beaumont notes, still has cultural currency in fine-art photography. “Even if our predominantly secular culture has largely abandoned its inheritance of a (Christian) hermeneutic tradition, the heritage-infused currents of visual culture in combination with the return of religion in global terms, demands its voice” (225). She encourages us to consider where and how and why Jesus is showing up in the medium of photography.

+++

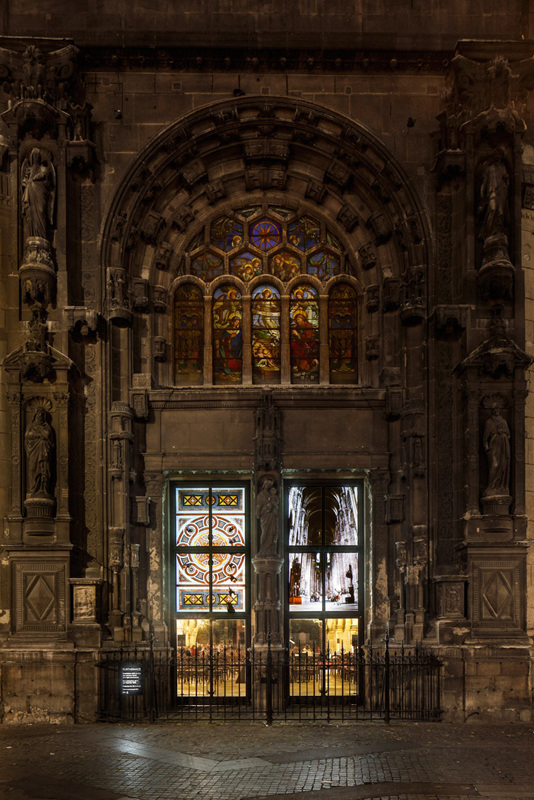

VIDEO: Deer in a Church: This short clip is one of the test scenes filmed on July 23, 2014, at the Église Saint-Eustache (Church of Saint Eustace) in Paris in preparation for a site-specific video installation commissioned for the church from Leonora Hamill, a photographic artist born in Paris and based in London and New York. The church is named after a Roman general who converted from paganism to Christianity during a hunt, after the stag he was pursuing turned to him and a cross appeared between its antlers, and he heard God speak, commanding him to be baptized. Eustace was martyred for his faith by Emperor Trajan in AD 118. His feast day is celebrated on September 20 in the Catholic Church and November 2 in the Orthodox Church.

The magnificent red deer (Cervus elaphus) in the video, a trained stag, is named Chambord. The installation he was filmed for, which was on view from December 4, 2014, to January 18, 2015, is titled Furtherance; a “making of” video can be seen here, and Hamill has posted another test scene on Instagram. Her director of photography for the project was Ghasem Ebrahimian.

From the artist’s website: “Shot on 35mm, the work weaves together traces of everyday activities within the church, unusual architectural points of view and a live stag . . . wandering through the space. Hamill transcribes the collective energy specific to this place of worship by retracing the steps of the church’s various occupants: priests, parishioners, tourists, soup-kitchen volunteers (on duty at the West Entrance every evening during winter) and their ‘guests’. These crossing paths constitute the social essence of the site. Their minimalist and precise choreography merges the human and spiritual sap of St Eustache.”

The footage of the majestic deer inside the majestic seventeenth-century sacred space—looking curiously around the high altar, the soaring candles reminiscent of trees in a forest—is breathtaking! Reminds me of Josh Tiessen’s Streams in the Wastelands painting series. Even nonhuman creatures praise the Creator.