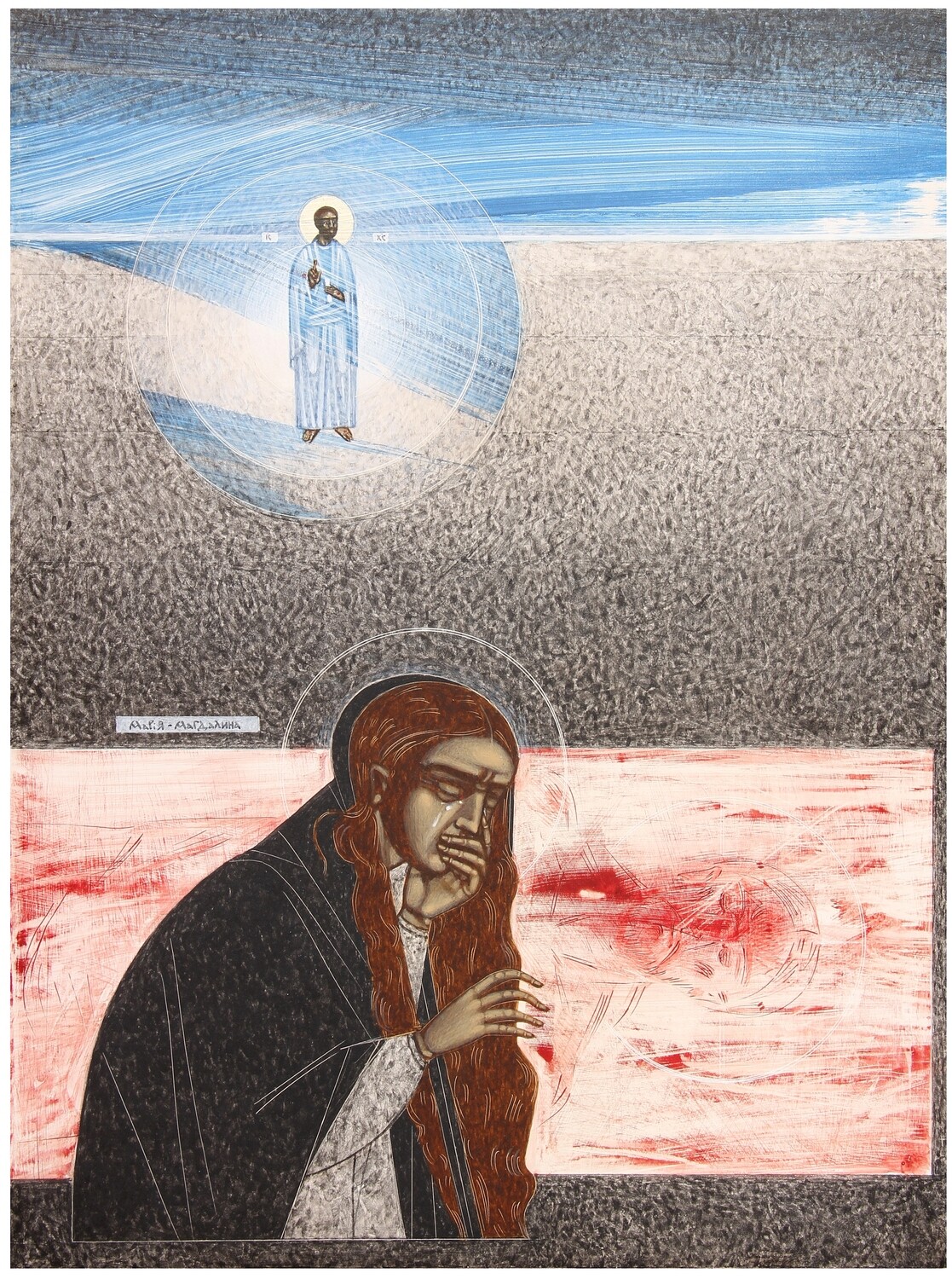

LOOK: Mary Magdalene Stood Crying by Kateryna Kuziv

LISTEN: “Weeping Mary” | Traditional American, 19th century | Arranged by Dan Damon and performed by the Dan Damon Quartet, feat. Sheilani Alix, on Beautiful Darkness, 2022

Is there anybody here like Mary a-weeping?

Call to my Jesus and he’ll draw nigh.

Is there anybody here like Mary a-weeping?

Call to my Jesus and he’ll draw nigh.Refrain:

Glory, glory

Glory, glory

Glory be to my God on high

Glory, glory

Glory, glory

Glory be to my God on highIs there anybody here like Peter a-sinking? . . .

Is there anybody here like jailers a-trembling? . . .

This early American spiritual was transmitted orally before first being recorded in The Social Harp (Philadelphia, 1855), a shape-note hymnal compiled by John Gordon McCurry (1821–1886). McCurry was a farmer, tailor, and singing teacher who lived most of his life in Hart County in northeastern Georgia. The Social Harp credits the music for “Weeping Mary” to him and gives it the year 1852, but I think that indicates not composition but notation and harmonization; in other words, McCurry is the arranger.

In the description of their 1973 facsimile reprinting of The Social Harp, the University of Georgia Press writes, “In the time between the [American] Revolution and the Civil War, the singing of folk spirituals was as common among rural whites as among blacks. This was the music of the Methodist camp meeting and the Baptist revival, and white spirituals in fact are known chiefly because homebred composers sometimes wrote them down, gave them harmonic settings, and published them in songbooks.”

I regard “Weeping Mary” as an Easter song, since the primary verse refers to Mary Magdalene standing outside the empty tomb weeping because she doesn’t know what happened to the body of her Lord (John 20). Then a man she supposes to be the gardener engages her in conversation—and turns out to be the one she’s been seeking, only he’s alive!

The jailer in the third verse refers to the Philippian jailer from Acts 16, tasked with guarding the prisoners Paul and Silas, who were falsely charged with disturbing the peace. One night an earthquake strikes, releasing the chains from the walls and breaking open the cell doors. The jailer raises his sword to kill himself to avoid the shame of having let his wards escape. But Paul alerts him that they’re still there, after which the jailer “fell down trembling” and asked the two what he must do to be saved. “Believe in the Lord Jesus,” they reply. After which he and his whole household convert to the new faith.

“Call to my Jesus and he’ll draw nigh,” the song promises.

Another “Weeping Mary” verse not in The Social Harp but that I’ve heard added in some renditions is “Is there anybody here like Thomas a-doubting?”

More subdued than the typical Easter fare, “Weeping Mary” testifies to the nearness of God in our sorrows, fears, doubts, and weaknesses. It embraces those who are anxious, grieving, or struggling, offering a gentle word.

I first learned this song from a recording by the American folk musician Sam Amidon, which I also really like:

In Brattleboro, Vermont, where he grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, he told NPR, shape-note singing was a social tradition, something that happened once a month, with singers moving to different people’s houses, including his own. His parents are the well-known folk musicians Peter and Mary Alice Amidon.

In his rendition he uses the grammatically incorrect but historically faithful verb that appears in original songbook, “Are there anybody . . .”

For a more vigorous jazz arrangement, which includes scat singing and a trumpet solo, see June April’s 2007 album What Am I?. She uses just the first verse.

And here’s a traditional performance in four-part a cappella by the Dordt College Concert Choir, directed by Benjamin Kornelis: