UPCOMING LECTURES:

I’m one of the artistic directors of the Eliot Society, a faith-based arts nonprofit in Annapolis. I’m really looking forward to our next two events this fall! If you’re in the area, I’d love for you to come out to these talks by a musician and a medievalist. They’re both free and include a time of Q&A and a small dessert reception afterward.

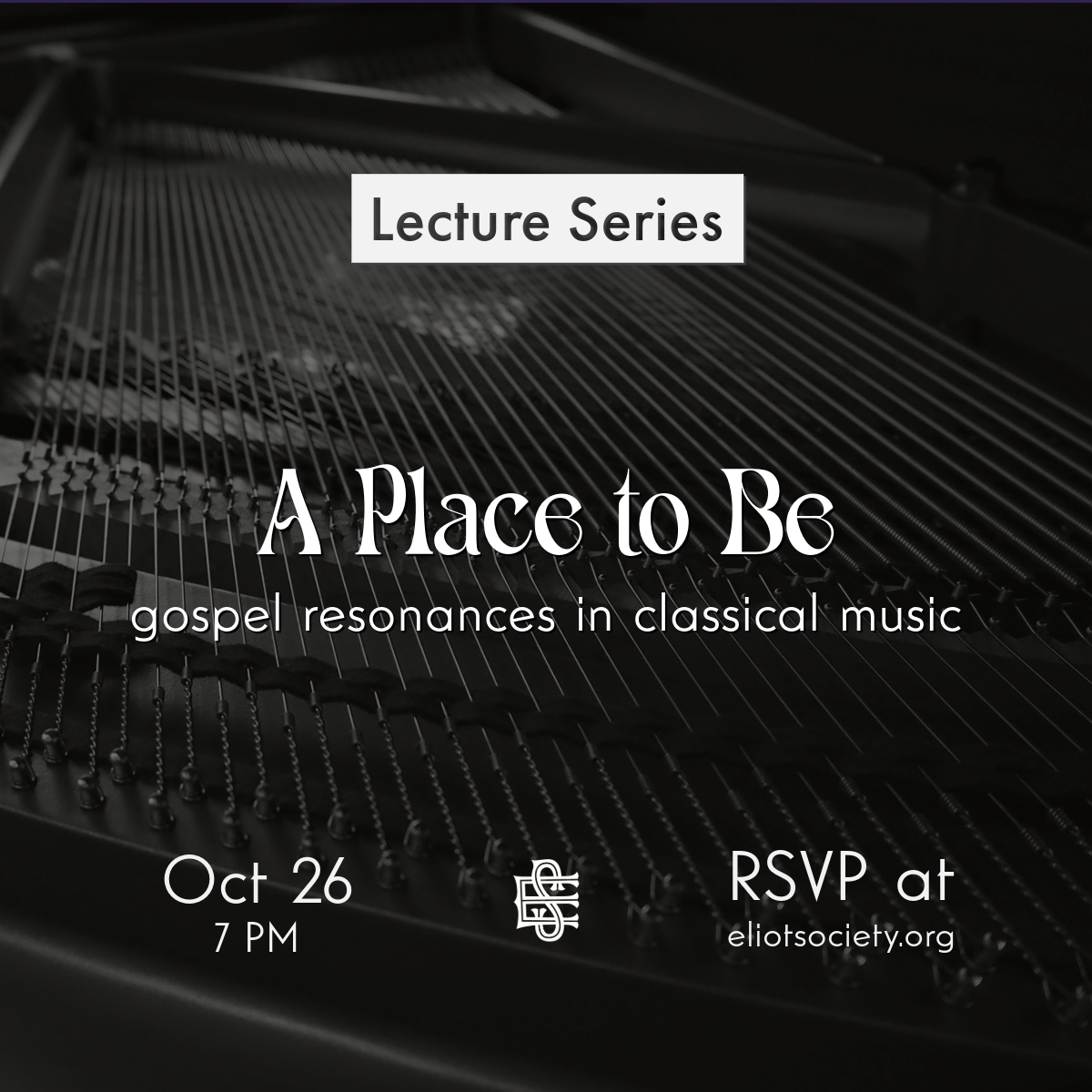

>> “A Place to Be: Gospel Resonances in Classical Music” by Roger Lowther, October 26, 2024, Redeemer Anglican Church, Annapolis, MD: “At its most basic, music is a collection of sounds. How those sounds are organized varies by country and culture and reflects their values, history, and heart-longings. Join Tokyo-based American musician Roger W. Lowther on a journey through the landscapes of Western and Japanese classical music and explore their unique and fascinating differences. Roger will lead from the piano as he demonstrates the musical languages of each tradition and show how they contain hidden pointers to gospel hope in a world full of suffering and pain.”

I’ve heard Roger speak before, and he’s very Jeremy Begbie-esque in that he does theology through instrumental music. As a bicultural person, a New Englander having lived in Japan for almost twenty years (ministering to and through artists of all disciplines), he brings a unique perspective. In addition to discussing the defining features of the Western versus Japanese classical traditions, he’ll be performing a few piano pieces from each.

>> “Christ Our Lover: Medieval Art and Poetry of Jesus the Bridegroom” by Dr. Grace Hamman, November 23, 2024, St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Crownsville, MD: “If there was a ‘bestseller’ book of the Bible in the European Middle Ages, it would be the Song of Songs. When read allegorically, in the manner of medieval theologians like St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the book tells the story of the romance between Christ and the soul that culminates in Christ’s love shown on the cross. This is a story of mutual pursuit, the pain of desire and sacrifice, sensual delight, and true union. The idea of Jesus as a longing lover of each individual soul appeared everywhere by the later medieval period, in art, poetry, sermons, and the devotional writings of men and women alike.

“These themes and images can strike us as strange, even uncomfortable. An illustrated poem for nuns depicted the Song of Songs like a cartoon strip. Prayer books of wealthy nobles portrayed Christ’s wounds intimately. Poets wrote Christ in the role of a chivalric, wounded knight weeping and waiting for his lady. And yet, examining this ancient imagery of Jesus our Lover together can challenge us to greater vulnerability with our Savior, to refreshed understandings of God’s hospitality, and, in the words of Pope Gregory the Great, can set our hearts ‘on fire with a holy love.’”

Grace is a fabulous teacher of medieval poetry and devotional writing, one whom I’ve mentioned many times on the blog before. Her Jesus through Medieval Eyes was my favorite book of 2023; read my review here. She has encouraged me to move in toward the strange and imaginative in medieval theology and biblical interpretation, because there’s often beauty and wisdom to be found there if we give it a chance. She has a keen awareness of the body of Christ across time and an appreciation for the gifts they’ve bequeathed the church of today, be they words, art, or whatever else.

+++

VIDEO: “Poet and Pastor: Christian Wiman and Eugene Peterson”: In this four-minute video from Laity Lodge, poet and essayist Christian Wiman and pastor and spiritual writer Eugene Peterson (best known for his Bible translation The Message) talk about prayer and spirituality. They each share a poem they’ve written: Wiman’s “Every Riven Thing” and Peterson’s “Prayer Time.” “People who pray need to learn poetry,” Peterson says. “It’s a way of noticing, attending.”

+++

ARTICLE: “Stop and read: Pope praises spiritual value of literature and poetry” by Cindy Wooden, National Catholic Reporter: On August 4 the Vatican published a letter by Pope Francis, a former high school lit teacher, on the important role of literature in formation. Read some highlights at the article link above, or the full letter here.

+++

SONG: “Teach Me How to Pray” by Dee Wilson: This jazz adaptation of the Lord’s Prayer premiered at Good Shepherd New York’s September 8 digital worship service. It is written and sung by Dee Wilson of Chicago.

+++

ARTICLE + PLAYLIST: “Latin American Fiesta!” by Mark Meynell: I always appreciate the selections and knowledge Mark Meynell [previously] brings to his 5&1 blog series for the Rabbit Room, each post exploring five short pieces and one long piece of classical music. This Latin American installment features Kyries from Peru and Argentina, a candombe air, a four-part Christmas anthem in Spanish creole from Mexico (I found an English translation!), an Argentine tango, and a dance chôro (Portuguese for “weeping” or “cry”) from Brazil. What diverse riches!

“Classical music, as conventionally understood, is not often associated with Latin America,” Meynell writes, “though, as we will see, this is a situation that needs rectifying. Some extraordinary soundworlds were being created long before the Conquistadores arrived from European shores, and together with the cultural impact of the transatlantic slave trade from Africa, the musical mix that resulted is unique. To put it at its most simplistic, we could say that the two key musical influences were the Catholic Church and the complex rhythms of percussion and dance; and often, it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.”

View more from the 5&1 series here. In addition to “Latin American Fiesta!,” among the thirty-three posts thus far are “Autumnal Mists and Mellow Fruitfulness,” “Musical Thin Places: At Eternity’s Edge,” “Music in Times of Crisis,” “The Calls of the Birds,” and “It’s All About That Bass.”

+++

ARTWORK: The Old Man and Death by Pedro Linares: Last month I visited the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, for the first time and was delighted to stumble upon an exhibition that had just been put up, Entre Mundos: Art of Abiayala. On view through December 15, it highlights collection works made by artists with personal or ancestral ties to Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The title translates to “Between Worlds,” and “Abiayala,” I learned, is a Guna (Kuna) word that means “land in its full maturity” or “land of vital blood”; it’s used by the Guna and some other Indigenous peoples to refer to the Americas.

For me the standout piece from the exhibition is The Old Man and Death by Pedro Linares, a dramatic tableau in the medium of cartonería (papier-mâché sculpture), a traditional handcraft of Mexico. Commissioned by the Wadsworth in 1986 for the artist’s MATRIX exhibition, it reinterprets Joseph Wright of Derby’s 1773 painting of the same name, one of the most popular works in the museum’s collection.

Regarding the Wright painting, Cynthia Roman writes that it

masterfully combines Wright’s ability to depict a literary narrative with his skill in rendering a natural setting with accuracy and keenly observed detail. The subject of this painting is based on one of Aesop’s Fables or possibly a later retelling by Jean de la Fontaine. . . . According to the tale, an old man, weary of the cares of life, lays down his bundle of sticks and seats himself in exhaustion on a bank and calls on Death to release him from his toil. Appearing in response to this invocation, Death arrives. Personified here as a skeleton, Death carries an arrow, the instrument of death. Illustrating the moral of the tale that it is “better to suffer than to die,” the startled old man recoils in horror and instinctively waves him off, reaching for the bundle as he clings to life.

The Linares piece and its inspiration are placed side-by-side in the gallery, which also displays an alebrije by the same artist, papel picado, painted skulls, an ofrenda, and Diego Rivera’s Young Girl with a Mask.