“Sonnet XVIII” by Lope de Vega

¿Qué tengo yo que mi amistad procuras?

¿Qué interés se te sigue, Jesús mío,

que a mi puerta cubierto de rocío

pasas las noches del invierno escuras?

¡Oh, cuánto fueron mis entrañas duras

pues no te abrí! ¡Qué extraño desvarío

si de mi ingratitud el hielo frío

secó las llagas de tus plantas puras!

¡Cuántas veces el ángel me decía:

«¡Alma, asómate agora a la ventana,

verás con cuánto amor llamar porfía!»

¡Y cuántas, hermosura soberana,

«Mañana le abriremos» – respondía,

para lo mismo responder mañana!

From Rimas sacras (Sacred Rhymes) by Lope de Vega (Madrid, 1614). Public domain.

Lope de Vega (1562–1635) was as astoundingly prolific Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist who was a key figure in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His 1,800-some plays encompass the categories of religious, mythological, historical, pastoral, chivalric, and comedies of manners. A known philanderer, Lope had multiple love affairs throughout his life; besides the four children he had from his two wives, he also had at least ten more by his mistresses. The death of his son in 1612, and then of his lover the following year, threw him into an existential crisis, and he turned toward religion, even joining the Catholic priesthood in 1614—but that path didn’t lead to the personal reform he had thought he wanted, as he continued his womanizing. He died of scarlet fever at age seventy-two.

Translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Lord, what am I, that with unceasing care

Thou didst seek after me, that thou didst wait,

Wet with unhealthy dews, before my gate,

And pass the gloomy nights of winter there?

Oh, strange delusion, that I did not greet

Thy blest approach! and oh, to heaven how lost,

If my ingratitude’s unkindly frost

Has chilled the bleeding wounds upon thy feet!

How oft my guardian angel gently cried,

“Soul, from thy casement look, and thou shalt see

How he persists to knock and wait for thee!”

And oh, how often to that voice of sorrow,

“Tomorrow we will open,” I replied,

And when the morrow came I answered still, “Tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow,” from Coplas de Don Jorge Manrique, translated from the Spanish; with an Introductory Essay on the Moral and Devotional Poetry of Spain by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Boston, 1833). Public domain.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882) was an American poet, educator, and linguist, best known for “Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Song of Hiawatha.” From 1829 to 1854, he was a professor of modern languages, first at Bowdoin College, his alma mater, and then at Harvard University. Though rooted in New England, he traveled extensively in Europe and was proficient in—besides his native English—Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Italian, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, and Polish, as well as Latin and Greek. He frequently translated poetry from those languages into English, his most influential translation being of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which brought that work to a wider English-speaking audience.

Translated by Geoffrey Hill

Based on the prose translation by J. M. Cohen in The Penguin Book of Spanish Verse, 3rd ed. (Penguin, 1988)

What is there in my heart that you should sue

so fiercely for its love? What kind of care

brings you as though a stranger to my door

through the long night and in the icy dew

seeking the heart that will not harbour you,

that keeps itself religiously secure?

At this dark solstice filled with frost and fire

your passion’s ancient wounds must bleed anew.

So many nights the angel of my house

has fed such urgent comfort through a dream,

whispered ‘your lord is coming, he is close’

that I have drowsed half-faithful for a time

bathed in pure tones of promise and remorse:

‘tomorrow I shall wake to welcome him.’

“Lachrimae Amantis” (Tears of the Lover), from the sonnet sequence “Lachrimae: Or, Seven Tears Figured in Seven Passionate Pavans” in Tenebrae by Geoffrey Hill (André Deutsch, 1978); compiled in Broken Hierarchies: Poems, 1952–2012 (Oxford University Press, 2014). Copyright © The Estate of Geoffrey Hill. Reproduced with permission of the licensor through PLSclear.

Sir Geoffrey Hill (1932–2016), a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, was an English poet and literary critic who is recognized as a principal contributor to those fields in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He was a Christian. From 1988 to 2006, he lived in the United States, where he taught literature and religion at Boston University, but throughout his career he also had professorships at Oxford, Leeds, and Cambridge. “Hill’s poetry is known for its barbed humor, personal intensity, and deep interests in culture, history, and religion,” Poets.org states, and for being dense and intellectually rigorous.

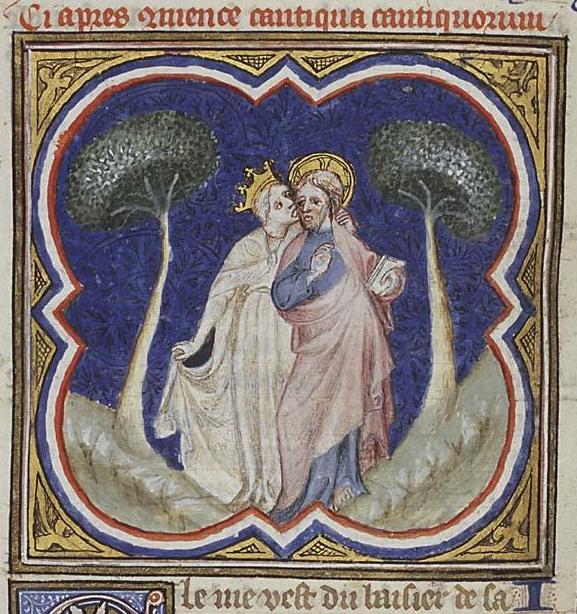

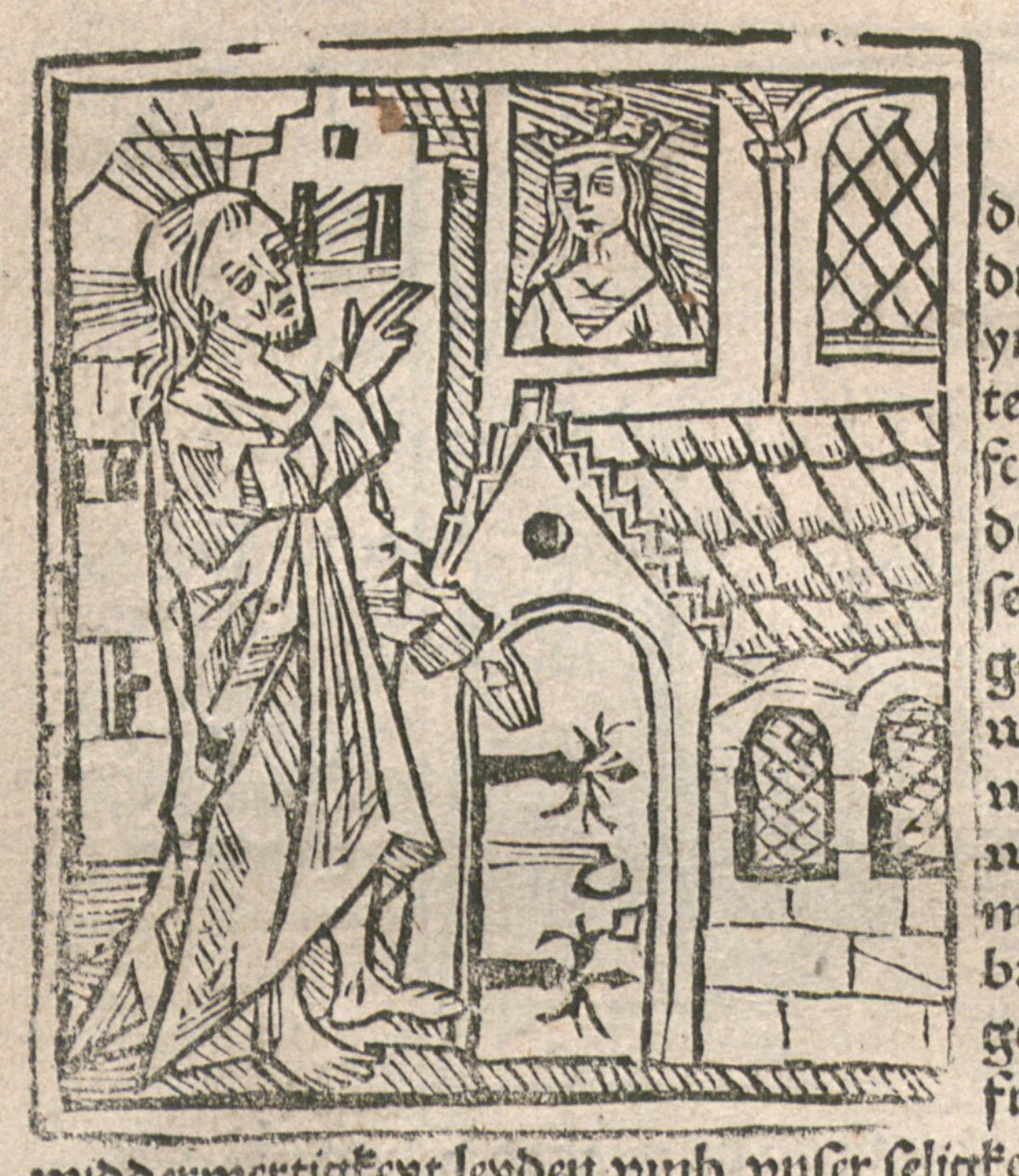

The eighteenth sonnet from Lope de Vega’s Rimas sacras—reproduced above in its original Spanish and in two English translations—portrays Jesus as a lover, knocking tenaciously to be let into his beloved’s heart. He stands outside at night in the cold, a coldness matched by the beloved’s indifference, for she says, “I’ll open tomorrow,” but then keeps putting off that promise to the next day and the next . . .

“The poet marvels at the persistence of divine love in the face of human ingratitude,” writes Colin Thompson in his journal article “‘The Resonances of Words’: Lope de Vega and Geoffrey Hill.” Lope mines the paradox of fiery passion and icy rejection, Thompson says, “pressing . . . the traditional language of Petrarchan and courtly love into the service of spiritual love.”

Lope derived the conceit of “¿Qué tengo yo?” from two biblical passages: one in the Old Testament and one in the New. Part of an ancient Hebrew erotic love poem, the first is Song of Solomon 5:2–6, in which a woman narrates how, lying in bed one night, she hears her lover’s call outside, but she waits too long to answer, for when she rises to open the door, he has gone:

I was sleeping, but my heart was awake.

The sound of my beloved knocking!

“Open to me, my sister, my love,

my dove, my perfect one,

for my head is wet with dew,

my locks with the drops of the night.”I had put off my garment;

how could I put it on again?

I had bathed my feet;

how could I soil them?

My beloved thrust his hand into the opening,

and my inmost being yearned for him.I arose to open to my beloved,

and my hands dripped with myrrh,

my fingers with liquid myrrh,

upon the handles of the bolt.

I opened to my beloved,

but my beloved had turned away and was gone.

My soul failed me when he spoke.

I sought him but did not find him;

I called him, but he gave no answer.

Chapter 3, verse 20 of Revelation, the final book of the Bible, implicitly references this passage. Christ exclaims to the church in Laodicea, “Listen! I am standing at the door, knocking; if you hear my voice and open the door, I will come in and eat with you, and you with me.” The extrapolation of the Song of Solomon romance to the relationship between Christ and the church, allegorized as his bride, would become common in early Christian biblical interpretation.

(Related post: “Undo thy door, my spouse dear”)

In his poem, Lope was also likely drawing on Augustine, a fourth- and fifth-century church father he is known to have read. In a famous passage from book 8 of his Confessions, Augustine describes how he initially responded to Christ’s wooing with indecisiveness:

I had no answer to make to you when you called me: Awake, thou that sleepest, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee light. And, while you showed me, wherever I looked, that what you said was true, I, convinced by the truth, could still find nothing to say except lazy words spoken half asleep: “A minute,” “just a minute,” “just a little time longer.” But there was no limit to the minutes, and the little time longer went a long way. (trans. Rex Warner)

Augustine’s conversion to Christianity was a slow one because of his slothful will. Many modern readers find that they relate to him in this—procrastinating making a faith decision because of force of habit and resistance to change. We worry what a commitment to Christ would demand of us, and it’s easier to just continue living for ourselves. So we settle for the status quo. Geoffrey Hill, in his translation of Lope, describes “the heart . . . / that keeps itself religiously secure,” punning on “religiously,” which in this case means “fervently, zealously”: the heart that, unwilling to be vulnerable, not daring to love and be loved, keeps itself closed to Christ.

Besides these biblical and patristic influences on Lope’s poem, Rafael Lapesa, in his 1977 book Poetas y prosistas de ayer y de hoy (Poets and Prose Writers of Yesterday and Today), identifies another: De los nombres de Cristo (The Names of Christ) by the Spanish Augustinian friar Luis de León, a masterpiece of Renaissance philosophical and theological thought first published in 1583. The “Pastor” (Shepherd) section in book 1 reads in part:

Madruga, digo antes que amanezca se levanta; o, por decir verdad, no duerme ni reposa, sino, asido siempre al aldaba de nuestro corazón, de contino y a todas horas le hiere y le dice, como en los Cantares se escribe: Abreme, hermana mia, Amiga mia, Esposa mia, abreme; que la cabeza traigo llena de rocio, y las guedejas de mis cabellos llenas de gotas de la noche.

He [Christ] rises early, I say; before dawn he rises. Or, to tell the truth, he neither sleeps nor rests but, always clinging to the knocker of our heart, continually and at all hours strikes it and says to it, as it is written in the Song of Songs: “Open to me, my sister, my love, my bride, open to me; for my head is covered with dew, and the locks of my hair are full of drops of the night.” (my translation)

Lope eulogized Luis in his seven-thousand-line Laurel de Apolo (1630) and clearly admired him.

The “Christ as lover” trope appears copiously in Christian literature, and Lope de Vega is but one poet who developed it, engaging it from a personal, confessional angle. Written right after his return to Christianity—after he finally opened the door to Christ—his “Sonnet XVIII” looks back on the many years he spent ignoring Christ’s entreaties so that he could pursue various lusts, which he would continue to struggle with for the rest of his life. He expresses wonder that Christ would love someone like him, and be so steadfast in his knocking. Unlike the knocking lover in the Song of Solomon, Christ stood before Lope’s door until Lope answered at last, “Come in.”