To him who loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood and made us a kingdom, priests serving his God and Father, to him be glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen.

Look! He is coming with the clouds;

every eye will see him,

even those who pierced him,

and all the tribes of the earth will wail on account of him.So it is to be. Amen.

—Revelation 1:5b–7

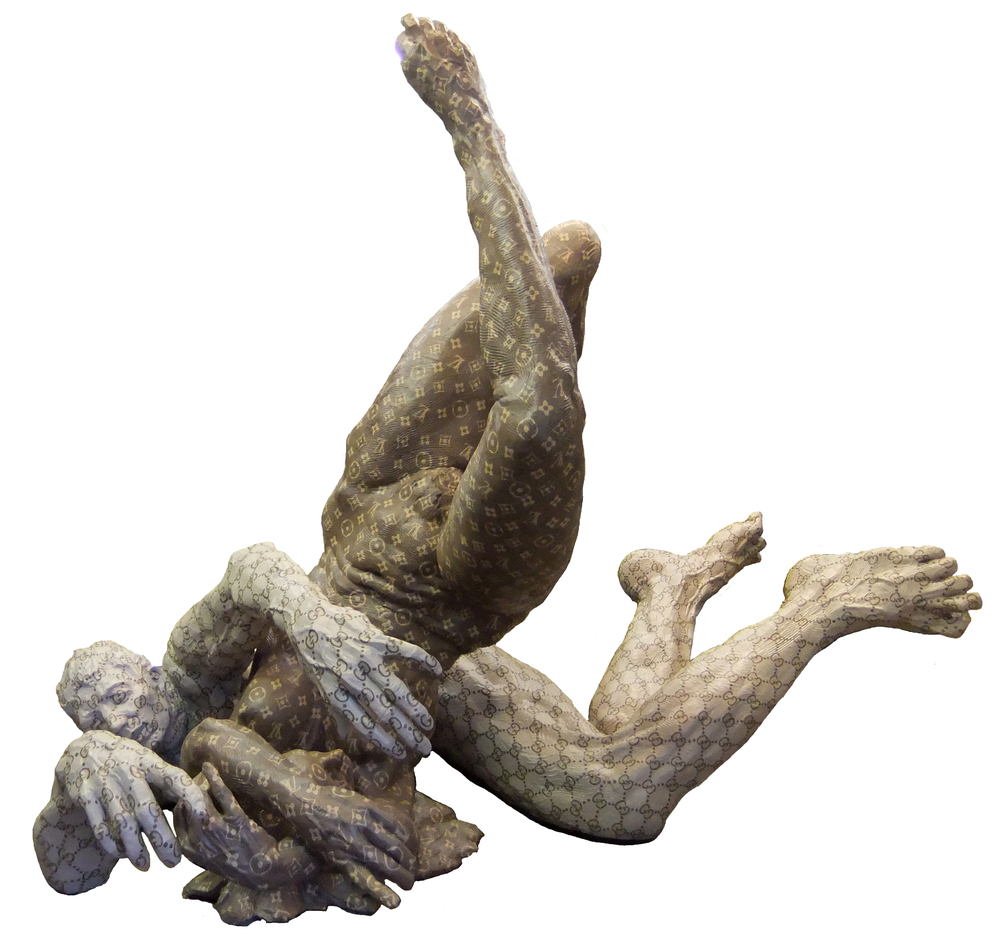

LOOK: The Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck

What is your reaction to this image? Terror? Awe? Gratitude? Disgust? Intrigue? Indifference?

I’m often repulsed by how the Last Judgment was interpreted by medieval and Renaissance artists, with graphic displays of torture intending to compel people to righteous living through fear. To be sure, the subject has made for some truly remarkable paintings, full of fantastical grotesqueries and masterfully executed—like this one—but I worry that the scare tactics such paintings use are not helpful and are even harmful.

Nonetheless, the Last Judgment is an unavoidable topic in scripture. The Bible refers several times to God as judge and describes a final accounting of sin upon Christ’s return, resulting in reward for the righteous and punishment for the unrighteous. It’s also in our creeds: “He [Jesus Christ] will come again to judge the living and the dead” (see 2 Tim. 4:1; 1 Pet. 4:5). Those who seek to be faithful to scripture must reckon with the idea of the Last Judgment. Advent, which is penitential in character, has historically been a period for the church to do that. As the Episcopal priest and author Fleming Rutledge points out in her published collection of Advent sermons, judgment is one of the four traditional themes of the season—the other three being death, heaven, and hell.

The early Northern Renaissance master Jan van Eyck’s Last Judgment from ca. 1436–38 is one of history’s most famous and most gruesome. “The diabolical inventions of Bosch and Brueghel,” writes art historian Bryson Burroughs, “are children’s boggy lands compared to the horrors of the hell [van Eyck] has imagined.”

The midground portrays the resurrection of the dead, who rise up out of their graves on land or at sea to be judged by Christ. One of the inscriptions on the frame is Revelation 20:13: “And the sea gave up the dead which were in it; and death and hell delivered up the dead which were in them: and they were judged every man according to their works.”

In the center Saint Michael the Archangel, dressed in his jewel-studded armor and with sword unsheathed, stands atop the giant batlike wings of Death personified, which are inscribed with the words CHAOS MAGNVM (“great chaos”) and UMBRA MORTIS (“shadow of death”). Death is a skeletal figure who excretes the damned through his bowels into hell’s dark slime, where bestial demons tear at, choke, devour, crush, and impale them. One man’s legs are being ripped apart at the anus.

Even kings and clergymen are part of the tragic death-heap—see the bishop’s miter, the cardinal’s galero, the royal crown. Not all who say, “Lord, Lord,” will enter heaven (Matt. 7:21); even the most outwardly pious will have their sins exposed on the last day, and those who prove to be hypocrites, who have harmed others and shamed God without repentance, will be thrown into the pit.

Shooting down like arrows into this pit is the double inscription ITE VOS MALEDICTI IN IGNEM ETERNAM (“Go, ye cursed, into everlasting fire”), taken from Matthew 25:41. And Deuteronomy 32:23–24, a warning from God via Moses to the people of God in their disobedience, is one of the inscriptions on the frame:

I will heap mischiefs upon them; I will spend mine arrows upon them. They shall be burnt with hunger, and devoured with burning heat, and with bitter destruction: I will also send the teeth of beasts upon them, with the poison of serpents of the dust.

Perhaps your chest is tightening right now, your stomach churning. How does this picture cohere with the God of love and mercy?

Look up.

See Jesus Christ, the Son of Man, coming in glory. See his glowing stigmata, beacons of love and mercy. He is dressed in a long, red, open mantle and is barefoot, revealing all five wounds. All around him, angels bear the instruments of his passion: the cross, the three nails, the crown of thorns, the lance, the sponge-tipped reed. See him flanked by all the ranks of the redeemed, including, on a larger scale, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, the first two witnesses of Jesus’s divinity.

VENITE BENEDICTI PATRIS MEI, read the inscriptions fanning out from Christ’s elbows: “Come, ye blessed of my Father” (Matt. 25:34). This good word is taken from Jesus’s parable of the sheep and the goats, in which he teaches that those who feed the hungry, clothe the naked, shelter the immigrant, care for the sick, and visit the imprisoned will be honored by God on the last day.

Another benediction is inscribed on the picture’s frame:

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them and be their God;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.” (Rev. 21:3–4 NRSV)

Van Eyck’s Last Judgment does not stand alone. For centuries it has been configured as a diptych (two-paneled artwork) with a Crucifixion on the left and is thus intended to be read in light of God’s supreme act of vulnerable love and self-giving:

Originally these two paintings very likely served as the wings of a triptych with a painted or sculpted centerpiece, or as the doors to a tabernacle or reliquary shrine. In 2019 the Metropolitan Museum of Art had the frames restored from their modern brass color to their original red.

So, what are we to make of this image today? Is there value in meditating on it?

I’ve presented it here, so I think it’s definitely worth knowing about. It’s a stunning art object that gives us a glimpse into the religious imagination of late medieval Christians. But I would also advise caution, especially to those who have been traumatized by hell teachings in the past. While Christians are called to cultivate a holy fear of God, a soberness around the weight of our sin and the power of God’s justice, this fear is not supposed to be the kind of fear that induces anxiety or paralyzes. That kind of fear will never lead us to love God.

We are never meant to think on hell apart from the grace Christ extends to us with his pierced and outstretched hands, which plead our case before God. Van Eyck holds both together in this painting, but the more visually immersive bottom half seems to indulge some pretty sick fantasies that could well generate an unhealthy fear of God if one were to stay stuck there, not to mention create the false impression that God is monstrously vindictive.

There is debate within Christianity, and has been since the patristic era, whether Jesus’s justice is merely punitive or ultimately restorative—that is, whether hell is a place of eternal conscious torment or a place where one is purged of evil and that will in the end be emptied. (There is biblical support for both views, which I won’t get into here.) There is also disagreement as to whether the Bible’s language about hell, such as its being a place of “fire” and “brimstone” (sulfur) (e.g., Rev. 21:8), is meant to be taken literally or figuratively.

Whatever the duration, physical nature, and ultimate purpose of hell, I want to emphasize that biblical passages about the Last Judgment ought not drive us to despair; they should drive us into the arms of Christ, who receives into his presence all those who trust in his merits and turn from their wickedness. The wounds that Christ so prominently displays in van Eyck’s painting are tokens of divine forgiveness as well as a model of the kind of selfless love we are to follow, a love vulnerable enough to receive injury but never to inflict it. Those who tumble into the depths of the underworld to be ravaged by externalizations of their own destructive evils have rejected the call to “do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with [their] God” (Mic. 6:8). Many of them are ones who on earth bore much power but used it to abuse others or were neglectful.

For more on the characterization of Jesus as judge in the art and theology of the Middle Ages (whose influence was felt in the Renaissance and later eras), see chapter 2, “The Judge,” of Jesus through Medieval Eyes by Grace Hamman. “The promise of answering unanswered evil, acknowledging the recognized and unrecognized wrongs of the mortal world—everlasting justice and compassion—is ultimately what Christ the Judge signifies. It’s a promise, a prophecy, and a call for action now,” Hamman writes (28). She discusses how neighborliness and fear of God are twinned: “Am I seeing the immortal being, the image of God, Jesus himself, in every person I encounter?” medieval imagery prompted viewers to ask (37). “Jesus the Judge reminds us of our divine community and invites a fear that guides us to love our neighbor as we love ourselves. . . . Fear of Jesus the Judge becomes a gift for our practice of justice, in the radiant light of his justice. Such a fear softens flinty hearts” (21, 36). In the chapter Hamman does also acknowledge the complications and misuses of fear in the medieval church and its legacy today.

I urge you to consider the van Eyck diptych in light of the retuned hymn below as you meditate on Christ’s return and his role as judge.

LISTEN: “Lo! He Comes with Clouds Descending” | Words by Charles Wesley, 1758 | Music by Thomas Vito Aiuto, 2012 | Performed by the Welcome Wagon on Precious Remedies Against Satan’s Devices, 2012

Lo! he comes with clouds descending,

once for favored sinners slain;

thousand, thousand saints attending

swell the triumph of his train.Ev’ry eye shall now behold him,

robed in dreadful majesty;

those who set at naught and sold him,

pierced, and nailed him to the tree,

deeply wailing, deeply wailing,

shall the true Messiah see.Ev’ry island, sea, and mountain,

heav’n and earth, shall flee away;

all who hate him must, confounded,

hear the trump proclaim the day:

Come to judgment, come to judgment!

Come to judgment, come away!

Alleluia, alleluia!

God appears on earth to reign.The dear tokens of his passion

Still his dazzling body bears,

Cause of endless exultation

To his ransomed worshippers.

With what rapture, with what rapture

Gaze we on those glorious scars!

Alleluia, alleluia!

God appears on earth to reign.Yea, amen! Let all adore thee,

high on thine eternal throne;

Savior, take the pow’r and glory,

claim the kingdom for thine own.

O come quickly, O come quickly;

everlasting God, come down.

O come quickly, O come quickly;

everlasting God, come down.

O come quickly, O come quickly;

everlasting God, come down.

I’m struck by the bright, celebratory, homey tone of the new tune Rev. Vito Aiuto gave this old Wesley hymn about Christ’s second coming. One might expect, with its verses about judgment, to have a dark or foreboding tone. But for those who are in Christ, his return, and even the day of judgment, will be an occasion of rejoicing!

Note that “dreadful” here is used in the archaic sense of inspiring awe or reverence.

This post is part of a daily Advent series from December 2 to 24, 2023 (with Christmas to follow through January 6, 2024). View all the posts here, and the accompanying Spotify playlist here.