LOOK: Bethlehem by Carola Faller-Barris

LISTEN: “Peace” | Words by Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1879, and Wilfred Owen, 1917 | Music by Peter Bruun, 2017 | Performed by the Svanholm Singers, dir. Sofia Söderberg, on Exclusive, 2019

When will you ever, Peace, wild wooddove, shy wings shut,

Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs?

When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? I’ll not play hypocrite

To own my heart: I yield you do come sometimes; but

That piecemeal peace is poor peace. What pure peace allows

Alarms of wars, the daunting wars, the death of it?Out there, we’ve walked quite friendly up to Death,—

Sat down and eaten with him, cool and bland,—

Pardoned his spilling mess-tins in our hand.

We’ve sniffed the green thick odour of his breath,—

Our eyes wept, but our courage didn’t writhe.

He’s spat at us with bullets and he’s coughed

Shrapnel. We chorussed when he sang aloft,

We whistled while he shaved us with his scythe.Oh, Death was never enemy of ours!

We laughed at him, we leagued with him, old chum.

No soldier’s paid to kick against His powers.

We laughed,—knowing that better men would come,

And greater wars: when each proud fighter brags

He wars on Death, for lives; not men, for flags.O surely, reaving Peace, my Lord should leave in lieu

Some good! And so he does leave Patience exquisite,

That plumes to Peace thereafter. And when Peace here does house

He comes with work to do, he does not come to coo,

He comes to brood and sit.

The text of this choral work by the Danish composer Peter Brunn combines two British poems: “Peace” by Gerard Manley Hopkins and “The Next War” by Wilfred Owen. Let’s look at each one separately, and then together.

“Peace” by Gerard Manley Hopkins

When will you ever, Peace, wild wooddove, shy wings shut,

Your round me roaming end, and under be my boughs?

When, when, Peace, will you, Peace? I’ll not play hypocrite

To own my heart: I yield you do come sometimes; but

That piecemeal peace is poor peace. What pure peace allows

Alarms of wars, the daunting wars, the death of it?

O surely, reaving Peace, my Lord should leave in lieu

Some good! And so he does leave Patience exquisite,

That plumes to Peace thereafter. And when Peace here does house

He comes with work to do, he does not come to coo,

He comes to brood and sit.

The Jesuit poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) wrote this curtal sonnet on October 2, 1879, after finding out he was reassigned from his role as curate at St. Aloysius’s church in Oxford to curate at St. Joseph’s in the industrial town of Bedford Leigh, near Manchester. He was apprehensive about this move to a place he described as “very gloomy” and unclean. The following decade, the last of his life, he would be plagued by melancholic dejection, which his later poems reflect. In addition to the internal disquiet he was experiencing in the fall of 1879, there was also an external lack of peace, as Great Britain was at war on three fronts—in southern Africa (against the Zulu kingdom), Afghanistan, and Ireland.

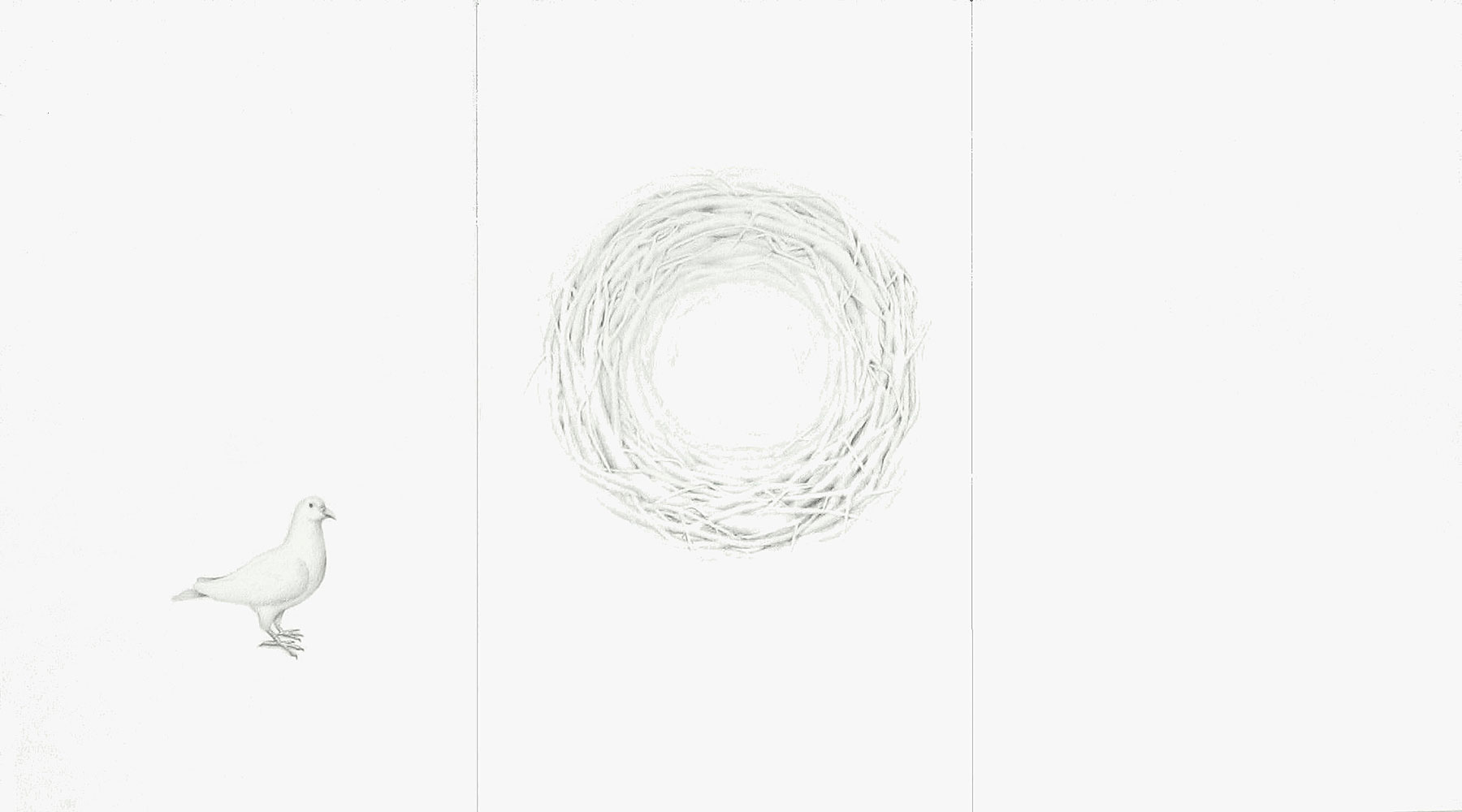

The speaker of the poem addresses Peace, an elusive dove, begging him to come settle down to nest, to incubate his eggs. “Brooding” here, writes J. Nathan Matias, is not a morose act but a generative, warmly creative one, birthing life.

Though the dove appears in scripture as a symbol of God the Spirit, in the last three lines of this poem he could be God the Son, the Prince of Peace. The people waited for generations upon generations for his arrival. And when he came, he was not all talk. He came with serious work to do; he came to hatch a newborn world.

This poem expresses yearning for peace in our hearts and in our lands—a permanent, holistic peace that only Christ can bring.

“The Next War” by Wilfred Owen

“War’s a joke for me and you,

While we know such dreams are true.”

—Siegfried Sassoon

Out there, we’ve walked quite friendly up to Death,—

Sat down and eaten with him, cool and bland,—

Pardoned his spilling mess-tins in our hand.

We’ve sniffed the green thick odour of his breath,—

Our eyes wept, but our courage didn’t writhe.

He’s spat at us with bullets and he’s coughed

Shrapnel. We chorussed when he sang aloft,

We whistled while he shaved us with his scythe.

Oh, Death was never enemy of ours!

We laughed at him, we leagued with him, old chum.

No soldier’s paid to kick against His powers.

We laughed,—knowing that better men would come,

And greater wars: when each proud fighter brags

He wars on Death, for lives; not men, for flags.

One of the premier poets of World War I, Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) was a British soldier whose poems lament the horrors of trench and gas warfare. His cynicism and transparency about war stood in stark contrast to the confidently patriotic verse written by earlier war poets.

Owen wrote “The Next War” while being treated for “shell shock” (PTSD) at Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh; he sent it in a letter to his mother dated September 25, 1917, writing the following week that he wanted her to show it to his youngest brother, Colin—for him “to read, mark, learn.” Owen was discharged from the hospital two months later and returned to the front lines of France, where he was killed in action on November 4, 1918, a week before the armistice, at age twenty-five.

He opens his ironic-toned sonnet with an epigraph from “A Letter Home” by Siegfried Sassoon, a fellow war poet he met at Craiglockhart, who became a friend and a mentor to him. (Bruun omits the epigraph in his choral work so that there’s a seamless transition between poems.) “Dreams will triumph, though the dark / Scowls above me,” Sassoon writes earlier in his poem, a poem that acknowledges the bleakness of war but, imagining the rebirth of a friend slain in battle, clings to the hope that it will soon be over and we can laugh it off.

Owen undercuts the optimism and solace in these lines with what follows in his own poem. The speaker of “The Next War”—which it’s pretty clear is the poet himself—personifies Death as a comrade whose intimate presence is normal among soldiers. He spits bullets, coughs shrapnel, and breathes stinking odors, and yet they ally themselves with him, sing Death’s song, go with him into battle.

Soldiers only delude themselves if they think they fight against Death, Owen asserts; they fight with him. Their nations’ governments will say they’re heroes, taking up arms to save lives and secure peace, but Owen rejects the idea that there’s anything noble, glorious, or effective about war. Soldiers kill men “for flags”—merely serving national interests—and their doing so never puts an end to war but only leads to another.

By bringing together these two texts, sandwiching Owen between Hopkins, Bruun gives a more hopeful framing to Owen’s disillusioned reflections on war, ending with the final image of a brooding dove. I like how the two poems play off one another. For example, Hopkins’s rhetorical question of “What pure peace allows / . . . the death of [peace]?” stands in starker relief when read in conjunction with Owen’s criticism of the ostensible rationale for war.

Bruun still honors Owen’s experience of being made far too familiar with death, his endurance of mortar blasts and mustard gas and all-around carnage, to no apparent end. Owen’s text starts at 2:11 of the video, where a menacing, march-like cadence enters. We feel the anxiety and the darkness of battle. The specificity of the poem resists us metaphorizing war—that is, applying the poem to a situation of inner turmoil (battling inner demons) only. This is physical combat between nations, which, of course, has severe psychological repercussions on the participants.

But at 5:33 the hushed tones of Hopkins return. Bruun had been attracted to Hopkins’s poem “Peace” for some time. In 2010 he wrote a setting of it for solo voice and flute, clarinet, horn, percussion, glockenspiel, violin, violoncello, and contrabass, and in 2016 he published a new setting, with Owens now inserted, as the second in a five-song cycle called Wind Walks for mixed choir and accompaniment, all five texts taken from Hopkins. He then adapted the song for the male-voice chamber choir the Svanholm Singers from Sweden, which is what I feature here.

The pointed and repeated “When” at the opening of Bruun’s piece, a word that Hopkins repeats three times in his poem, is powerful, an echo of the familiar biblical refrain, “How long, O Lord?” If we read Peace as Christ, then the poem is a prayer, asking Christ to come home to us, to our world—to spread his wings over it and nurture it back to life.

In Hebrew thought, shalom, “peace,” is not a passive thing, merely the absence of war. It’s the active presence of God and an all-encompassing state of completeness, soundness, health, safety, and prosperity.

Shalom is what we long for, especially during Advent. It’s what scripture promises will come someday—but now, its lack is keenly felt. It may occasionally flit and hover nearby, but then it flies off again.

As the church, may we embrace “Patience exquisite, / That plumes to Peace thereafter,” as we await Christ’s return, in the meantime preparing his way through acts of righteousness and reconciliation.