Mark Cazalet (b. 1964) is a contemporary artist based in London whose work centers on color and balances empiricism and lyricism. He works across media—painting, drawing, printmaking, and (in collaboration with fabricators) stained glass, etched and engraved glass, printed enamel on glass, tapestries, and mosaics. A major part of his career has been fulfilling ecclesiastical commissions and making sacred art. But all of his work, regardless of subject matter, is shot through with a sacramental impulse.

Last year Cazalet made a series of twelve “Advent Stations” that move circuitously through the story of Jesus’s first coming, marked as it was by mystery, vulnerability, risk, and glory. These include modernized versions of scenes you’d find in traditional Infancy of Christ cycles, such as the Annunciation to Mary, the Annunciation to the Shepherds, the Dream of the Magi, and the Flight to Egypt, but also new ones, drawing us into the grand sweep—sometimes rushing, sometimes quiet—of gospel hope. “The overarching theme,” he told me, “is pregnancy, birth, nurturing, waiting, escape, migration, and finally, in the mistle thrush’s morning song, the greeting of the new day’s limitless potential.”

The artist’s choice of substrate is unique: He painted his stations in oil on domestic wooden objects, such as bread boards, meat and cheese boards, children’s lunch trays, washboards, chapati rolling boards, and a baker’s peel. By using these ordinary boards mainly from home kitchens, Cazalet further situates the biblical Advent story in the everyday. That many of the boards are used for preparing or serving bread underscores Jesus’s self-declaration as “the living bread that came down from heaven,” whose flesh Christians eat ritually as a means of interabiding (John 6).

Cazalet’s Advent Stations debuted last December at his home church, St Martin’s in Kensal Rise, London, where they were installed one per week from Advent through Candlemas. The project was a collaboration with fellow parishioners Richard Leaf, who wrote a poem for each station, and Pansy Cambell, who calligraphed the poems.

That exhibition spawned interest from Chelmsford Cathedral in Essex, where all the artworks and poems are on display from December 1, 2025, through February 2, 2026. The cathedral is already home to two commissioned works of Cazalet’s: the monumental multipanel painting The Tree of Life and an engraved and etched glass window depicting St. Cedd.

The word “station” in the title of Cazalet’s recent series refers to a stopping place along a route. In the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church developed a devotional practice known as the Stations of the Cross, which breaks down the passion of Christ into fourteen distinct episodes fit for contemplation. The idea was that those who could not travel physically to Jerusalem for Lent to walk the Via Dolorosa (the processional route Jesus took to Golgotha) could at least walk the path in spirit, using a series of images as prompts to pause, pray, and reflect.

(Cazalet also made a set of twenty Stations of the Cross in 2024.)

Used by Christians in various denominations, this practice has been adapted for other seasons of the church year. While there are no official Advent Stations or Stations of the Nativity, Cazalet has come up with twelve.

All photos in this article are by the artist and are used with his permission.

Advent Station 1: The Breath of God

A mystical visualization of the Word becoming flesh, the first station has two configurations. In its closed form, it shows the mouth of God blowing through space, the divine breath coalescing around a woman’s uterus to form an embryo, the child who will be called Jesus. Wisps of blue swirl dynamically around this firstborn of new creation.

The triangular shape evokes the Trinity, as the Incarnation was an act involving Father (initiator), Son (enfleshed one), and Holy Spirit (overshadower / inseminating agent).

In the exhibition, an attached ribbon instructs viewers, “Lift me.” When you do, the bottom board flips up to reveal a pool of swimming sperm cells, as God created the male gamete needed to make a male child and supernaturally (nonsexually) deposited it into Mary, where it fertilized one of her eggs.

The virginal conception of Christ is a mystery beyond knowing; no amount of scientific head-scratching will bring us closer to understanding the mechanics, nor do we need to. But I like the reminder from this unusual artistic interpretation that all the necessary human genetic material was present—Mary supplying hers, and God supplying the rest. Jesus was not some kind of alien transplanted into a human womb, but rather was made up of all the human stuff we are, and grew by stages inside his mother over a period of nine months. And yet, while fully human, he’s also—marvel of marvels—fully God.

On the round board below, we see that the isolated uterus from the first view belongs to Mary, who lies in bed while Joseph serves as ultrasound technician, shining a light that discloses the still-developing Christ child on a video monitor.

Advent Station 2: John the Baptist on the Beach

The breath/wind motif is subtly carried over into this second Advent station, with sailboats lining the top of the center board.

This scene shows a young John the Baptist playing on the beach, with his parents, Zechariah and Elizabeth, lounging in swimsuits under a nearby umbrella. John crouches in the sand, pouring water from a seashell (the implement he uses to baptize Jesus in many traditional paintings, most famously Piero della Francesca’s) onto toy figurines who have queued up for the affusion. The water cuts a mini river through the sand, alluding to the Jordan.

The two side panels, which show a close-up of an open ear and an open mouth, likely refer to, in his prophetic ministry as an adult, John’s hearing the word of God and proclaiming it. His is “the voice of one crying out in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord; make his paths straight’” (Mark 1:3). John is regarded as an Advent figure because, by preaching repentance from sin, he prepared the people for the coming of the Messiah.

Advent Station 3: The Annunciation

The Annunciation, portraying the angel Gabriel’s message to Mary that she has been chosen to bear God’s Son, is one of the most frequently depicted biblical scenes of all time. How could any artist possibly make it new?

Cazalet refreshes the encounter by showing Gabriel dipping down headfirst from the heavens, the unconventional orientation perhaps a playful allusion to the topsy-turvy nature of Christ’s kingdom. He reaches across the gap to touch the belly of Mary, a young Black woman in a polka-dot dress who is seated on the floor with her eyes closed, rapt in prayer. This consensual touch is what effects the Incarnation.

Mary wears blue and even exudes a blue aura, blue being her traditional color, associated with heaven (the sky realm) and hope. Gabriel’s skin has a golden sheen—the color of divinity, purity, holiness. The coming together of blue and yellow creates green, symbolizing life, growth, and renewal.

Advent Station 4: Bethlehem Motel

The innkeeper couple in Bethlehem are a cultural invention, biblical scholars tell us, spawned by a misleading English translation of Luke 2:7, which says “there was no room for them [Mary and Joseph] in the inn” (KJV). The Greek word translated “inn,” kataluma, more properly means “guest room”: Because the census had brought many out-of-towners to the area, the guest rooms of Joseph’s relatives were full, but they made space for the pregnant couple in the lower room of the house where animals were kept for the night.

Despite the lack of an innkeeper character in scripture, it has become a popular element in storytelling about the Nativity in art, song, and sermons, as it prompts us to consider whether we are making room for Christ in our busy, overcrowded lives. And not just Christ, but anyone in need—of shelter or other forms of care.

Cazalet shows Mary and Joseph approaching a motel door as the female owner, sympathetic, comes out to greet them. A niche above their heads, hovering like a thought bubble, shows what the couple desires: a place to give birth and to lay their son.

Advent Station 5: The Incarnation (A Blessing Conferred)

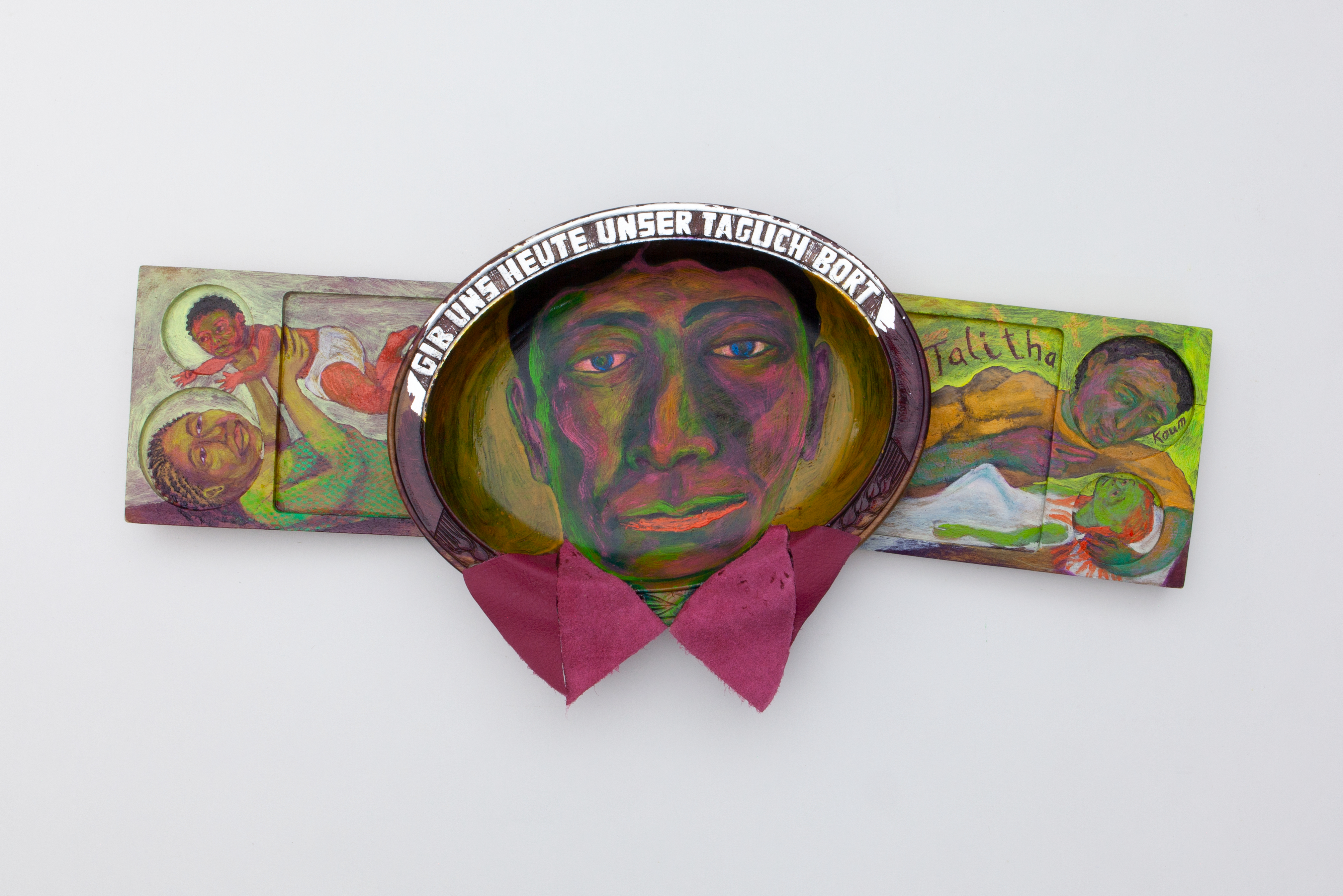

The fifth station features an unconventional combination of images. The left board shows Mary lying on her back, holding the wiggly infant Christ above her. She beams with maternal love.

On the right board, an adult Christ, similarly positioned, leans over the dead daughter of the synagogue leader Jairus. “Talitha koum,” Jesus gently instructs, cradling the girl’s head—Aramaic for “Little girl, get up” (Mark 5:41). With his words, she rises back to life.

The central image, a Head of Christ, is painted on a wooden bread plate from Germany—these plates were sometimes also used as church collection plates—whose rim reads, “Gib uns heute unser täglich brot” (Give us this day our daily bread). Carved sheaves of wheat poke out from under Jesus’s pink cloth collar.

“My intention is that Mary’s love for her son as she raised him taught him the care and compassion to want to help a child in extremis,” Cazalet told me. “The man is formed by the mother’s love, and our childhoods set the pattern of our response to others.”

Notice how, from behind the Christ head, the two adjoining boards emerge like wings, suggesting freedom.

Advent Station 6: The Shepherds See the Star

The sixth station portrays the glory of the Lord rippling across the night sky above three shepherds tending their flocks. Content and unassuming, they are gathered round a warm fire when suddenly, an angel appears to announce to them the birth of Christ. One of the shepherds cowers in fear while another gesticulates toward a brightly beaming star in the near distance—rendered with a Tunnock’s milk chocolate tea cake wrapper.

Advent Station 7: The Magi Dreaming

Having followed a star to Jerusalem from their home back east, the magi enter the court of Herod to inquire where they can find the newborn king of the Jews whom the star heralds, to pay him homage. Herod hadn’t heard of such a king, but immediately he feels threatened—“king of the Jews” is his title—and, unbeknown to the visiting dignitaries, decides to crush this young rival. After consulting with Jewish scholars, he discerns Bethlehem as the birthplace. He divulges this information to the magi and asks them to report back once they’ve found the child so that he, too, can honor him. He hides his true motive under a lie.

The magi have a transformative encounter with Jesus in Bethlehem. Falling asleep after that momentous day, they receive a warning from God not to return to Herod. So they avoid him on their way back home.

As in medieval visual treatments of the Dream of the Magi, Cazalet has the magi sharing a bed. (There’s nothing salacious about it—it’s just a compositional practicality, to show the three men in one space, having the same dream at the same time.) Their toes peep out from under the covers. That surface, by the way, is flat—Cazalet skillfully creates the illusion of convexity through painting, suggesting bodies underneath.

Beside the magi’s heads are three small personal objects: earbuds, glasses, and dentures, which allude to the proverbial principle “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” “I was musing if this trinity of pilgrim searchers were perhaps aspects of the one true pilgrim, parts of a single whole disciple,” the artist told me.

Advent Station 8: Herod Syndrome

Thwarted by the magi, Herod fumes with rage. He will not be dethroned by this so-called messiah. So he orders his soldiers to kill all the boys in Bethlehem aged two and under, thinking that Jesus will be among them. In his self-obsession, he cares nothing for the good of the people; he cares only for the consolidation of his own power.

Station 8 is Cazalet’s modern take on the Massacre of the Innocents. At the helm of a computer keyboard is a presidential figure launching a missile on whomever he has deemed the enemy, while other likeminded autocrats—I believe that’s Saddam Hussein, Kim Jong Un, Vladimir Putin, and Adolf Hitler—look over his shoulder approvingly, their faces reflected endlessly in mirrors using a technique called mis en abyme (“put in the abyss”). This panel, the transferring surface of a baker’s peel, sits at a height to emphasize the pompousness of rulers like Herod, who see themselves as above others and above the law.

Such an attitude can have dire consequences. “Below we see the devastation of a civilian population, defenceless against the technological onslaught,” Cazalet describes, “and the perpetual streams of migrants fleeing who knows where to be vilified as more foreign mouths to feed.”

The power mania that gripped Herod, that led to his lashing out in violence, is still alive and well today in national and global politics.

Advent Station 9: The Flight to Egypt (Forced Migration)

To protect their son from Herod’s murder decree, Mary and Joseph flee with him across the border to Egypt. Cazalet reimagines their flight through the lens of today’s refugee crisis. In station 9, the Holy Family boards an inflatable raft, braving choppy seawaters in search of asylum. They’re bathed in a menacing red.

On the adjoining panel, border patrol officers, with flashlights and batons, stand on the shore, seeking to bar the entry of strangers into their land.

Advent Station 10: The Exiles Return

Egypt grants refuge to the Holy Family, and they settle there for an undisclosed period of time—until Joseph receives word from an angel that it’s safe to return to their homeland.

Station 10 shows the family arriving at sunset in their beloved Nazareth, all their belongings reduced to what could fit in a single backpack. As they approach a tree-lined boulevard, Jesus clings to his mother’s back, looking behind at where they’ve come from. He has not yet known this town but will come to love it. He will call it home until his ministry beckons him beyond it more than two decades later.

Advent Station 11: Faithful Waiting and Watching (Anna and Simeon)

This is my favorite of all the stations. While the Presentation of Christ in the Temple is standard fare in Christian art—showing Mary handing Jesus to Simeon, a devout Jew interpreted by most artists as a priest, forty days after Jesus’s birth, with Joseph and the prophet Anna standing off to the side—Cazalet isolates the elderly Anna and Simeon, zeroing in on their faithful act of waiting for the Messiah.

Illuminated by candlelight, Anna knits a scarf, communing with God in the solitude, while Simeon fingers a string of prayer beads. Their eyes are weary and downcast, and yet they possess a steadfast hope that their Savior is on his way.

Linking their two spaces is the ark of the covenant, a sacred wooden storage chest plated in gold and topped by two hammered-gold cherubim. Containing the tablets of the law, Aaron’s rod, and a pot of manna, the ark was kept in the holy of holies, the innermost sanctum of the temple, where it signified God’s presence.

Waiting can often feel useless—like nothing’s happening or will ever happen. But Anna and Simeon continued to wait on the Lord, to count on his promise. And finally, before they died, they were granted the grace to see and to hold the One they had so fervently longed for: the Christ, Emmanuel, “God with us.”

Advent Station 12: The Mistle Thrush Greets the New Day

The Advent path we’ve just walked has included an unplanned pregnancy, persecution, and displacement but also miracles, play, and surprise.

Cazalet’s Advent Stations end with a bird in a tree, singing its heart out as a pink and yellow dawn spreads across the sky. The twisted branches become streamers, blowing as if in celebration. (There’s that breath of God again!) Out of the bird’s beak shoots light.

The board that forms the grassy ground is incised with knife marks, perhaps suggesting woundedness—although maybe it’s a turning over of the soil to promote new growth.

The flame-like hues in and around the tree evoke the burning bush of Exodus 3, from which God spoke his name: I AM THAT I AM.

This Advent tree, bare yet lively, calls us to embrace each new day as a gift from the One who is and was and is to come, remembering how Christ came to show us who God is and to feel and heal our brokenness, and he will come again to make all things new.

The Advent Stations by Mark Cazalet, with accompanying poems by Richard Leaf rendered in calligraphy by Pansy Cambell, are on display at Chelmsford Cathedral in eastern England through February 2, 2026. They are available for sale, but until they’re purchased, Cazalet wants to show them in other churches and cathedrals. They’re tentatively scheduled for exhibition in Southwark Cathedral in London during Advent 2026.