PRESS RELEASE: “The Creative Arts Collective for Christian Life and Faith Announces Launch of Its First Competitive Request for Proposals (RFP)”: The Creative Arts Collective for Christian Life and Faith [previously], an endowed initiative run by Belmont University in Nashville, has just opened its online Letter of Inquiry form for the 2025 Spring Grant Program. Form submission deadline: December 6, 2024.

The RFP is open to interested individual artists, artist collaboratives, church leaders, scholars/theologians, arts-affiliated organizations, faith-based nonprofit organizations, or institutions who reside or operate in the United States. Eligible applicants may submit proposals with requests ranging from $50,000 to $250,000 that may be used over one year. Chosen applications will then be requested to submit a full grant proposal for the competitive 2025 Spring Grant Program.

The 2025 grant-seeking theme is “Performing Shalom.” Applicants are invited to reflect the theme in their project or program, but it is not a requirement when applying for a grant. Please click here for more information.

+++

SUBSTACK POST: “On Artists, Kings, and Mending the Multiverse” by Houston Coley: A wise and rousing reflection after the US presidential election. Houston Coley is an Atlanta-based documentary filmmaker, video essayist (YouTube @houston-coley), podcaster, and writer on TV and film, who “cultivat[es] spiritual imagination around art and pop culture,” as one person put it.

+++

POEM: “What to Do After Voting” by James A. Pearson: The poet James Pearson shared this poem from his collection The Wilderness That Bears Your Name (Goat Tail Press, 2024) on Instagram on Election Day last Tuesday. He writes, “What’s driving [all our voting] are two things: Our common needs for love, safety, and belonging. And our often conflicting attempts to meet them. Rumi wrote: ‘Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.’ History is offering us a fork in the road. Let’s turn towards what we can do—vote. Then let’s find each other in that field and do the long, slow work of building a world where everyone has access to the love, safety, and belonging they need.” [HT: Amy Peterson]

He writes further on his website, “This poem doesn’t pretend to be a full prescription for what our country needs. It’s just my way of acknowledging that all electoral choices are imperfect. Because even more important is what happens between elections—the long, slow work of building a culture of love and justice for our politicians to live up to. And the better we do that work, the better our options will be next time elections come around.”

+++

SONG: “Apsáalooke Praise Song,” sung by Sarah Redwolf (née Bullchief): Sarah Redwolf is a member of Crow Nation in Montana and a follower of the Jesus Way whose Apsáalooke name is Baawaalatbaaxpesh (Holy Word). Here she sings a praise song by her grandmother Xáxxeáakinnee (Rides the Painted Horse). The Apsáalooke lyrics are below; I couldn’t find an English translation, and the artist has not yet returned a message I sent ten days ago, but I believe the song was written with Christian intent, as Christianity has been in Sarah’s family for generations. Her father, Duane Bull Chief, is a traveling Pentecostal preacher and the leader, with his wife, Anita, of Bull Chief Ministries, and Sarah has often led worship for church services and other Christian gatherings. What a beautiful voice!

Akbaatatdíakaata Dáakbachee

Huúlaa-k awúaleel akósh

Sáawe dée kush

Ahóohkaáshi, ahóohkaáshi, áaaaweelee-éehAkbaatatdíakaata

Baléelechiisaa awúaleel akósh

Ahóohkaáshi, ahóohkaáshi, áaaaweelee-éeh [source]

+++

LECTURE: “The Sign of Jonah” by Matthew Milliner, Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Illinois, October 3, 2019: This is the first lecture in a three-part series by art historian Matthew Milliner called The Turtle Renaissance that he developed into the book The Everlasting People: G. K. Chesterton and the First Nations (InterVarsity Press, 2021). (Here’s a well-written book review that I concur with; you can read an excerpt from the book here.) In the video, the talk starts at 8:49, followed by a response by Capt. David Iglesias, JD, of Kuna nation at 1:03:31, and then a Q&A starting at 1:25:27.

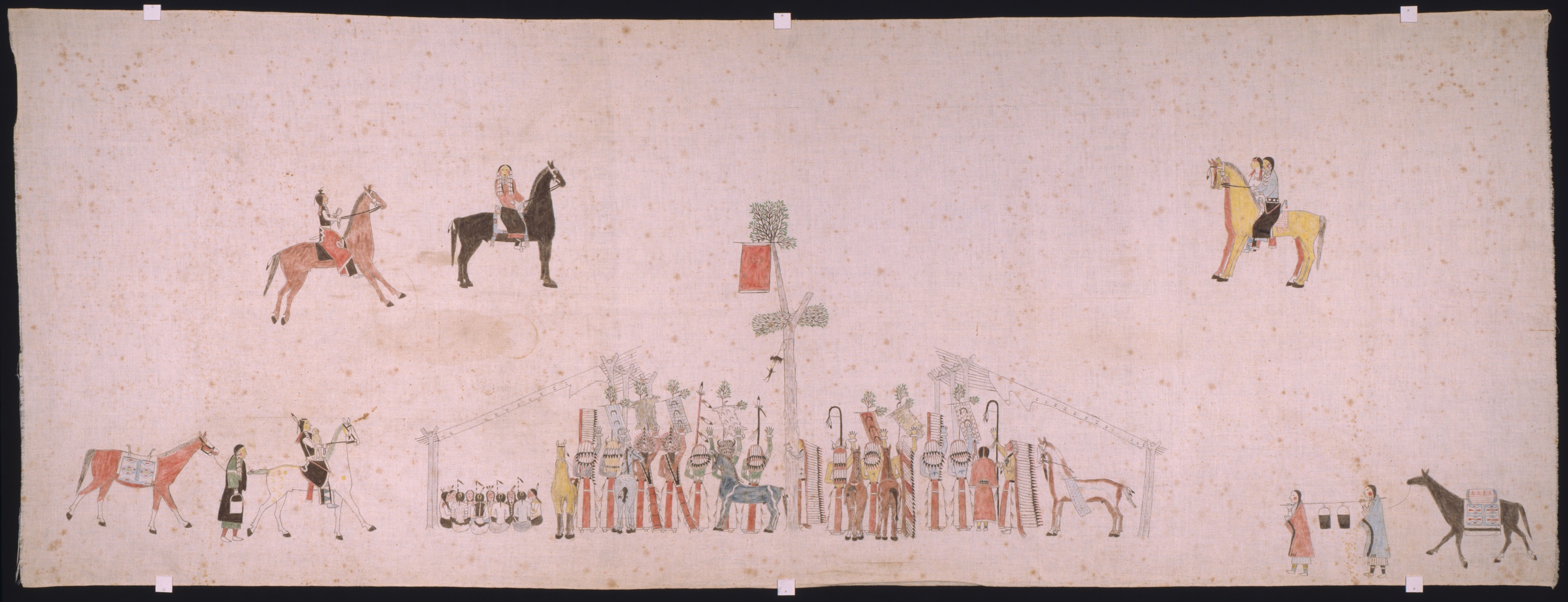

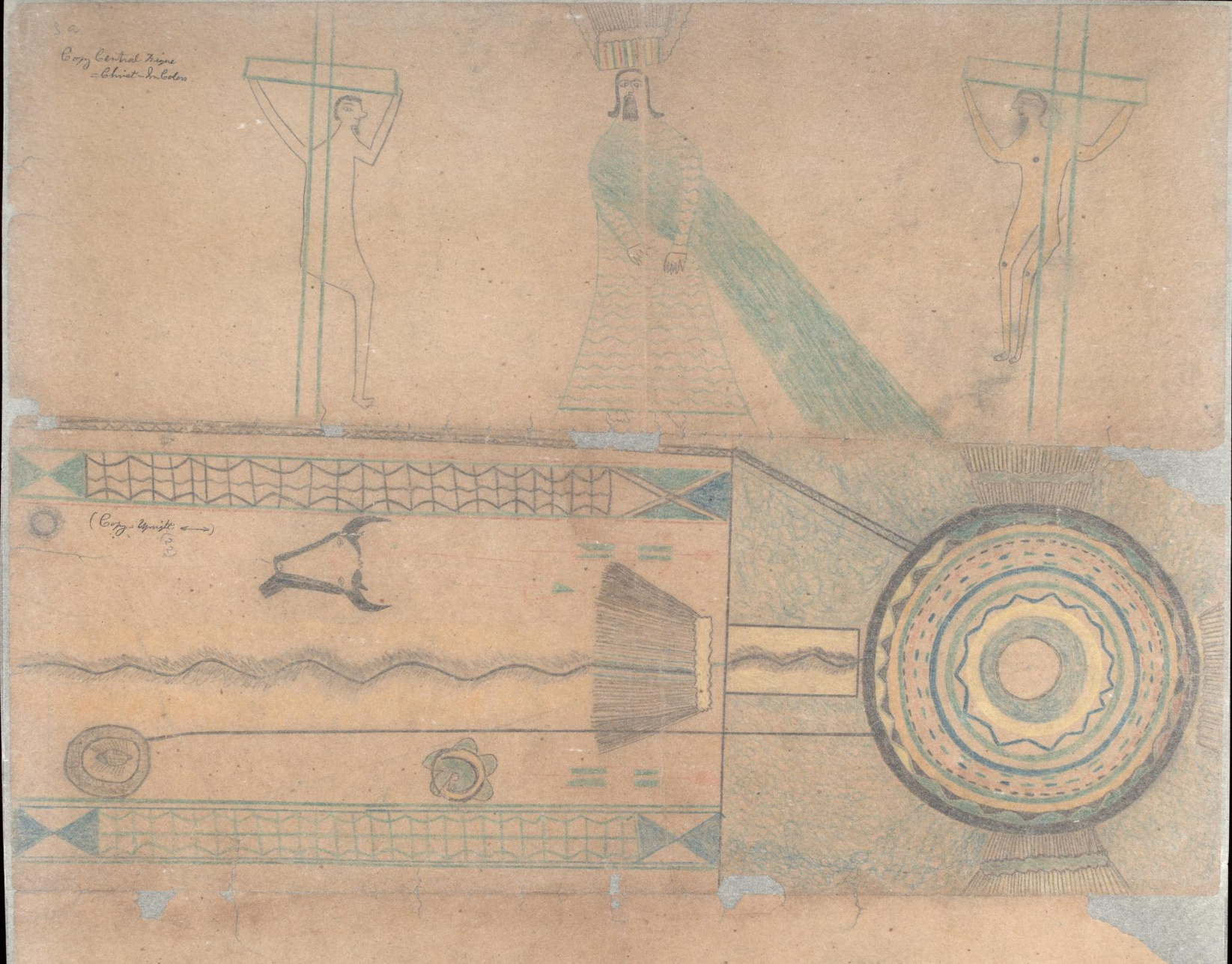

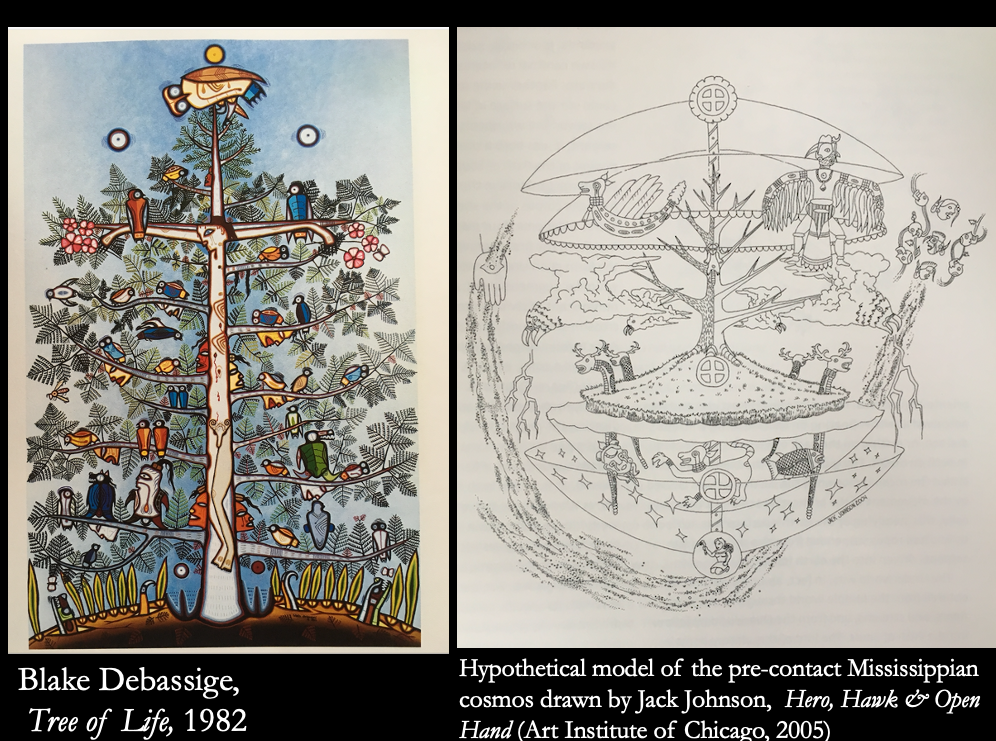

In conversation with Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man, Milliner explores contact points between Christianity and Indigenous North American art, symbol, ritual, and history. The discussion touches on pre-contact petroglyphs carved into Teaching Rocks near Peterborough, Ontario (one of them, a sun figure, quite possibly representing Gitchie Manitou, the Great Spirit—Christ incarnate?), the Sun Dance (which many Native Christians interpret as a prophecy of the Crucifixion), the Ghost Dance (about resurrection and renewal), the Mishipeshu (an underwater panther often representing death, which some Native Americans used to characterize white settlers), the Thunderbird, Black Elk’s vision of a mysterious figure with holes in the palms of his hands, and the cross as an axial tree conjoining the above and below worlds. Just as ancient Hebrew culture contained pointers to Christ, so too, Milliner argues, do the Indigenous cultures of North America. Artists, preachers, and visionaries from among the Ojibwe, Kiowa, Lakota, and other peoples are “our North American Virgils,” he says—Virgil being a Latin poet whose Fourth Eclogue, written around 40 BCE, prophesied the birth of a divine savior who would usher in a golden age.

There’s much more I could say, as there’s certainly more nuance and complexity to this, but instead let me simply refer you to Milliner’s lecture and finely footnoted book. There’s also a great audio interview with Milliner about The Everlasting People from November 2021, conducted by Jason Micheli for the Crackers and Grape Juice podcast.

+++

VIDEO: Chapel service led by Terry Wildman, November 6, 2023, Azusa Pacific University, California: Earlier this year I got to have dinner with Terry Wildman [previously] and his wife, Darlene, who form the Nammy Award–winning musical duo RainSong. It was exciting to hear all about their work with Native InterVarsity and other projects. They live in Maricopa, Arizona, on the traditional lands of the Pima and Tohono O’odham peoples. Wildman, who has both Ojibwe and Yaqui ancestry, was the lead translator, general editor, and project manager of the First Nations Version: An Indigenous Bible Translation of the New Testament. (The nativity narrative from the FNV translation of the Gospel of Luke, you may be interested to know, was adapted into an illustrated book titled Birth of the Chosen One: A First Nations Retelling of the Christmas Story, which just released this fall.)

Last November Wildman led a worship service for Azusa Pacific University students. Here are the key elements:

- The opening three minutes are an animated video of the gospel story, narrated by Terry Wildman to a flute accompaniment by Darlene Wildman

- 8:12: Blessing of the Gabrielino-Tongva people

- 9:38: The Lord’s Prayer (FNV)

- 10:57: Sermon: “Worship in Spirit and in Truth” (John 4:1–42)

- 21:17: Reading of Psalm 8 (FNV)

- 23:48: Song: “Lift Up Your Heads” by Terry and Darlene Wildman, based on Psalm 24

- 28:40: Song: “Hoop of Life” by Terry Wildman – Native American powwows often feature hoop dancers, who dance a prayer that Creator will bring harmony and goodwill to all the gathered people. Wildman says, “I look at Jesus and I call him the Great Hooper Dancer. Because he’s the one who ever lives to pray for us, to make intercession for us, and when he dances his prayer, he is bringing harmony and balance to the whole world, to the whole universe. And if we follow him, if we give our hearts to him, he will produce that harmony and balance in us and with each other.”

- 35:56: Song: “Nia:wen” (Mohawk for “Thank You”) by Jonathan Maracle of Broken Walls

- 45:29: Closing prayer