WORSHIP SERVICES:

In February I shared a few of the Vespers services offered at this year’s Calvin Symposium on Worship at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which I was privileged to attend. Here are two of the full-fledged services that give you a sense of what the larger corporate gatherings are like. (The theme was Ezekiel.) I love the cross-cultural sharing that goes on, learning new songs alongside others, getting refreshed by prayer and formed by liturgy, sitting under the teaching of wise ministers of God from various backgrounds, and taking Communion with friends new and old.

>> “God’s Glory Departs from Israel,” February 8, 2024 (with bilingual Korean-English music and liturgy): This worship service was led in Korean and English by the Woodlawn Christian Reformed Church Choir, directed by Chan Gyu Jang; the Living Water Church Worship Team, directed by Yohan Lee; and members of the Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary Korean communities. Rev. Dr. Anne Zaki from Evangelical Presbyterian Seminary in Cairo, Egypt, preached on Ezekiel 10–11.

This is an example of bilingual worship done really well! (I’ve seen it done poorly: with lack of communication of intention, one-sided involvement in the design or execution, inadequate pronunciation coaching for non-native speakers at the mic, unclear instructions that create confusion as to who is supposed to say or sing what, unintelligibility, etc.) I’m so grateful for all the creativity and thoughtfulness that went into creating this service—with a special shout-out to the bulletin designers and livestream technicians.

The bulletin provides this note on bilingual worship:

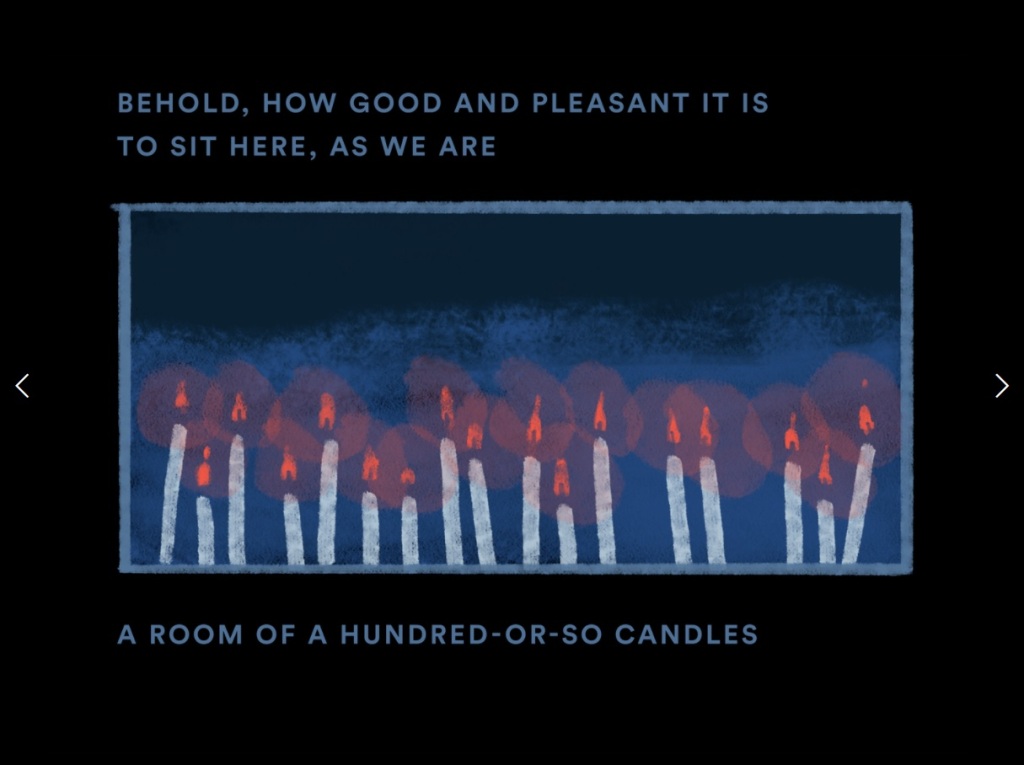

Two languages are intertwined together in this bilingual service. At times, words are spoken in one language, and their translation—unspoken—is provided on the righthand column; at times, the leaders demonstrate to the congregation how to sing or speak the words through transliteration; and at other times, the leaders and congregation converse in both languages, providing meaning to each other, so that no word sung or spoken is left unintelligible. We seek understanding and order in the sharing of our gifts.

In our pursuit, however, we practice patience and hospitality. In this service, we are called not only to speak and sing, but also to listen, to take turns. By listening, we create a room—a shelter—for travelers and strangers in this land, since language and music have power to transport one’s soul homeward. By taking turns, we practice the pace and posture of dialogue, even monolingual dialogue.

Beautiful! Here are three songs I’ll call out for special attention:

- 9:14: “Joo-yeo, Come, O Lord” by Sunlac Noh: This song, which is particularly well suited for Advent, originated in the Anglican Church of Korea and was translated into English last year by Martin Tel (see podcast interview below). The version we sang at the symposium preserves two of the Korean titles for Jesus.

- 23:36: “우리에게 향하신” (Woo-ri-e-ge Hyang-ha-shin) (Never-Ending Is God’s Love) by Jin-ho Kim, based on Psalm 117:2: Sung entirely in Korean, this was used as a refrain during the Assurance of Pardon and the Prayers of the People. A simple, repeated line, either sung or spoken, is a good way to involve non-native speakers of a given language.

- 1:14:37: “주님 다시 오실 때까지 / Rise, My Soul, Till Jesus Comes Again” by Hyeong-won Koh: The closing song is a charge to continue in the way of Jesus, all the way Home. The vocalists on stage sang the song themselves in its original Korean the first time through, and then we all joined in in English for the second time.

All the song credits are provided in full in the YouTube video description.

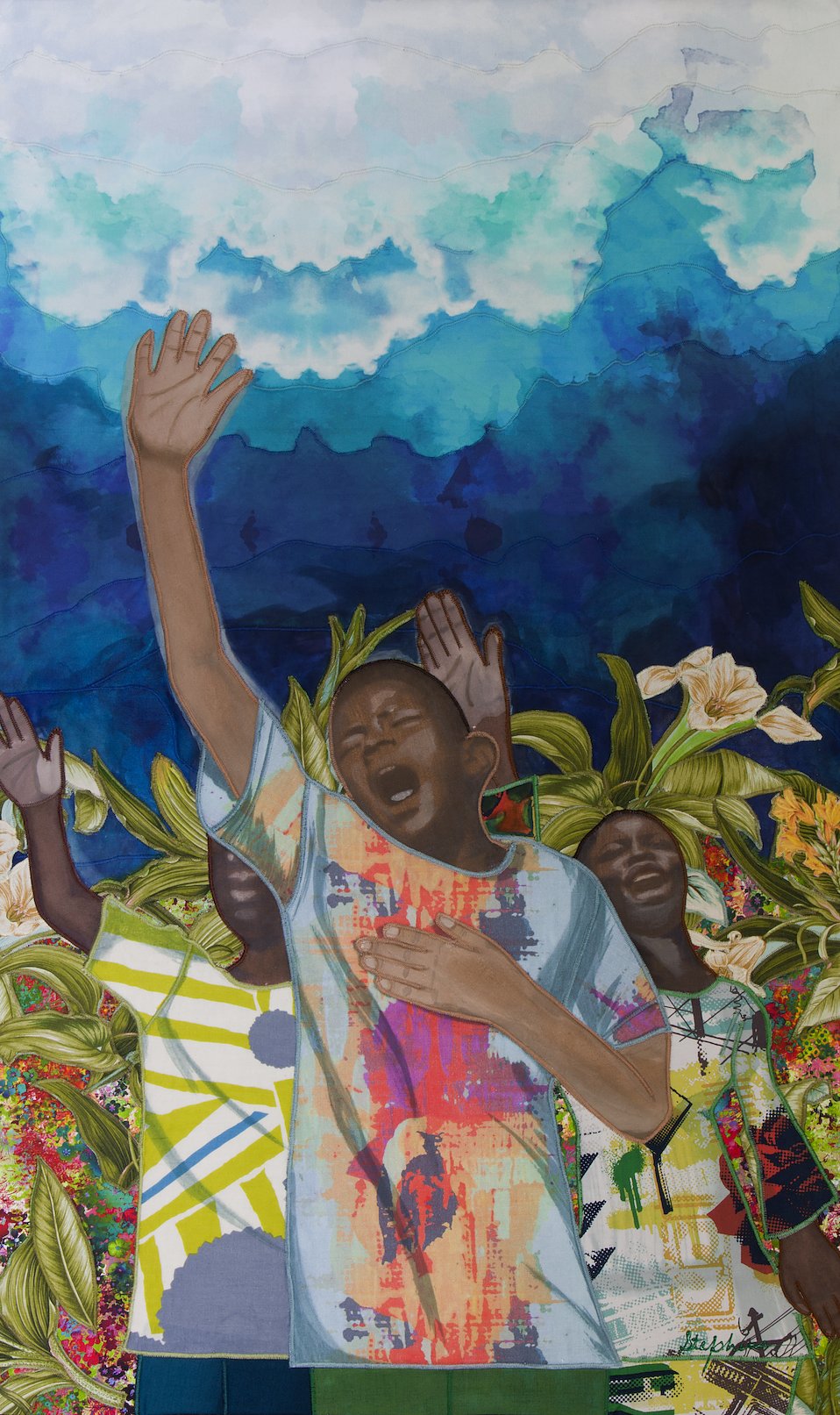

>> “The Valley of Dry Bones,” February 8, 2024: Rev. Dr. Brianna K. Parker from Dallas, founder of Black Millennial Café, preached on the famous Ezekiel 37 passage, and the Calvin University Gospel Choir, directed by Nate Glasper, led music, along with guest artist Ruth Naomi Floyd.

I want to especially draw your attention to 23:31, where Floyd premieres an extraordinary new song of hers, “God Breathed.” It opens and closes with a flute, and in between are her powerful jazz vocals, singing an original poetic text based on Ezekiel 37, accompanied by James Weidman on piano. (Update: Here’s a standalone video of the song.)

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “Fighting Back Against the Storms of Life with Martin Tel,” Psalms for the Spirit: Host Kiran Young Wimberly interviews Martin Tel, director of music at Princeton Theological Seminary and senior editor of Psalms for All Seasons: A Complete Psalter for Worship (2012), about the Psalms—the importance of psalm singing in his Dutch Reformed upbringing; the Psalms as a form of resistance and protest; the Psalms as a means of praying our own prayers and those of others; our need to overhear some psalms as being prayed against us (that is, have you considered that you might be someone else’s oppressor?); and ideas for framing a psalm with a refrain, such as these:

- Combine the Charles Albert Tindley gospel song “The Storm Is Passing Over” with Psalm 57 (“In the shadow of your wings I will take refuge, until the destroying storms pass by . . .”). Sing into the storm.

- Choose a Gospel passage of someone in deep lament (e.g., the ten lepers in Luke 17:11–19), surround it with Psalm 88, and have the congregation sing “Kum Ba Yah” (Gullah for “Come by Here”) in minor mode as a refrain (“Someone’s crying, Lord . . .”). A choir can hum the spiritual while the reader(s) read the scriptures.

- Intersperse the verses of Psalm 14 (“Fools say in their heart, ‘There is no God.’ . . . They have all gone astray . . .”) with the refrain “Prone to wander, Lord, I feel it . . .” to help the congregation members see their own foolishness instead of assuming it’s someone else who’s the fool.

+++

ARTICLE: “The Mysteries of Liturgical Sincerity” by John Witvliet, Worship (reprinted Pray Tell), May 2018: Some Protestants accuse the more liturgically inclined Christians, like me, of not valuing sincerity in worship because we value prewritten prayers and other set forms. But just because something is scripted or done habitually does not make it “rote” or “empty.”

“Among my mostly Protestant students, no theme is more contested, misunderstood, or cherished” than sincerity, writes John D. Witvliet, director of the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and professor of worship, theology, and congregational and ministry studies at Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary. In this article he explores several different definitions of sincerity, which vary widely across cultures, centuries, philosophical frameworks, and Christian traditions, and then offers six “corrective lenses” to common astigmatisms in the free-church Protestant way of viewing the world: outside-in sincerity, vicarious sincerity, trait sincerity, symbiotic sincerity, sincerity as gift, and aspirational sincerity.

This article is SO GOOD. I have been greatly influenced over the years by Dr. Witvliet’s teachings on liturgical formation, and I strongly encourage you all to read this piece.

+++

EKPHRASTIC POEMS:

An ekphrastic poem is a poem written in response to a work of visual art. Here are two examples I like from the past two years:

>> “Christ Preaching” by Keene Carter, Image: “I forgive the absent boy,” begins this poem based on a Rembrandt etching, directing our attention to the young child in the foreground who has turned away, disinterested, from Jesus’s sermon, drawing on the ground instead. Jesus gives grace to those in the crowd with averted gazes or who are distracted, simply continuing to preach on on the virtue of empathy—of seeing yourself in others—and on true life.

>> “L’Angélus” by Seth Wieck, Grand Little Things: The Angelus is a traditional Christian prayer whose name comes from its opening words in Latin, “Angelus Domini” (The angel of the Lord). For centuries it was prayed by the faithful three times a day—at 6 a.m., noon, and 6 p.m.—the times announced by the ringing of bells from church towers. In the nineteenth century Millet famously painted two peasant farmers at dusk pausing from their labor in the fields to bow their heads and pray the Angelus. Seth Wieck interprets the painting through poetry, homing in on the part of the prayer that says, “Let it be done to me according to thy word,” expressing an attitude of surrender to God’s will. Wieck imagines the hard life of the man and woman shown pulling up potatoes from the earth—the same earth in which, shortly hence, they’ll bury a child, lost to sickness. The poem becomes a meditation on death, harvest, and acceptance.

DONATE

I am committed to keeping all Art & Theology posts freely available to all; no paywalls here. To help me make a part-time living developing content for the site, would you consider donating to the work, or supporting my research by buying me a book from my Amazon wish list? I appreciate it!