BOOK: Meditations of the Heart by Howard Thurman (1953): I’ve just finished reading this book, and I think it would make an excellent companion for Lent. Written by Rev. Dr. Howard Thurman, a minister, theologian, professor, and civil rights leader, it consists of 152 one- to two-page meditations that he originally wrote for use by the congregation of Fellowship Church in San Francisco, a racially integrated, interdenominational church he cofounded in 1944. Some of the entries are prayers, some anecdotes, some reflections on scripture or spiritual topics, some expressions of desire or intent. For me, the book really started picking up in the second half. In part 5, several of the meditations begin and/or end with a mantra-like saying, such as “I will keep my heart open to truth and light” or “Teach me to affirm life this day!”—something short and memorizable to keep in the pocket of your heart and turn over and over.

Here’s an example of one of the meditations:

I want to be more loving. Often there are good and sufficient reasons for exercising what seems a clean direct resentment. Again and again, I find it hard to hold in check the sharp retort, the biting comeback when it seems that someone has done violence to my self-respect and decent regard. How natural it seems to “give as good as I get,” to “take nothing lying down,” to announce to all and sundry in a thousand ways that “no one can run over me and get away with it!” All this is a part of the thicket in which my heart gets caught again and again. Deep within me, I want to be more loving—to glow with a warmth that will take the chill off the room which I share with those whose lives touch mine in the traffic of my goings and comings. I want to be more loving!

I want to be more loving in my heart! It is often easy to have the idea in mind, the plan to be more loving. To see it with my mind and give assent to the thought of being loving—this is crystal clear. But I want to be more loving in my heart! I must feel like loving; I must ease the tension in my heart that ejects the sharp barb, the stinging word. I want to be more loving in my heart that, with unconscious awareness and deliberate intent, I shall be a kind, a gracious human being. Thus, those who walk the way with me may find it easier to love, to be gracious because of the Love of God which is increasingly expressed in my living.

Included in the volume are prayers for a gracious spirit in dealing with injustice, for placing our “little lives” and “big problems” on God’s altar, for laying ourselves bare to God’s scrutiny, for “when life grows dingy,” for the kindling of God’s light within us, “to be more holy in my words,” to learn humility from the earth, and for an enlarged heart that makes room for Peace.

+++

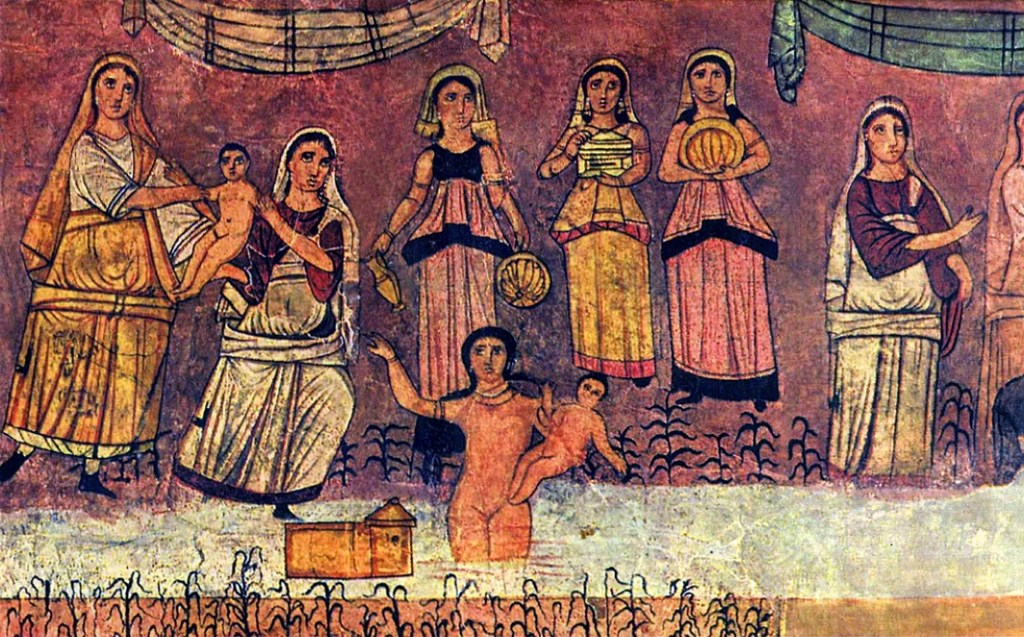

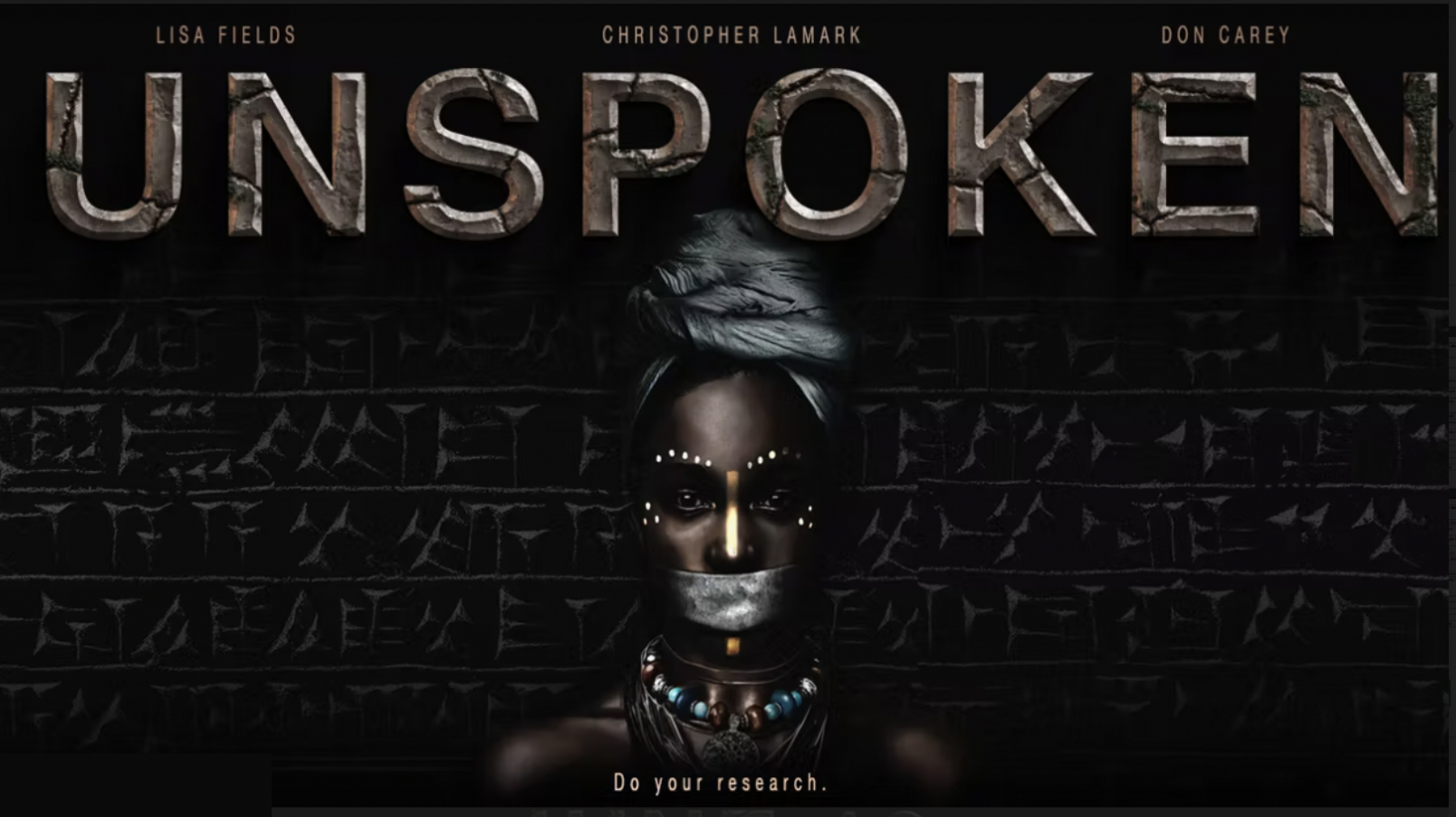

DOCUMENTARY: Unspoken, dir. Christopher Lamark (2022): This feature-length film takes an in-depth look at early African Christianity and its enduring heritage in African diaspora communities in America, dispelling the notion that Christianity is exclusively a white man’s religion. Director Christopher Lamark and his team interview historians, religious scholars, and cultural influencers, including Dr. Vince Bantu, Rev. Dr. Esau McCaulley, Rev. Dr. Charlie Dates, Lecrae Moore, and Sho Baraka, who reveal that Africans accepted Christianity of their own agency long before colonization or the slave trade, not just in the North but in sub-Saharan Africa as well. Bantu even points out that the Reformation was well underway in Africa a hundred years before Martin Luther, as the Ethiopian Christian monk Estifanos led a movement to bring the church’s practices more in line with scripture and to challenge abuses.

The false narrative that the Black church was born from those who drank the Kool-Aid served to them by their white oppressors has done a lot of damage, imposing shame and deterring young Black people from the Christian faith. That’s why it’s so important to correct this misinformation, to let people know that colonialism and slavery didn’t bring Christianity; it mutated it. At a time when much of white America was corrupting the gospel, Blacks preserved it, their ancient religious heritage, for subsequent generations.

Unspoken was produced by Lisa Fields of the Jude 3 Project, and Don Carey. It is streaming for free on TUBI.

+++

SYMPOSIUM: Embodied Faith and the Art of Edward Knippers, September 20–21, 2024, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Charlotte, NC: Sponsored by the Leighton Ford Initiative in Theology, the Arts, and Gospel Witness, this year’s Gordon-Conwell theology and arts symposium will center on the paintings of Edward Knippers, from Arlington, Virginia. In addition to an exhibition of over two dozen of Knippers’ works, there will be talks by artists Steve Prince, Bruce Herman, and Rondall Reynoso and theologians Natalie Carnes, W. David O. Taylor, and Kelly Kapic, as well as a dance performance by Sarah Council and a drum circle led by Olaniyi Zainubu and David Drum.

“‘Disembodiment is not an option for the Christian.’ This statement by visual artist Edward Knippers is a guiding principle in his work, which features the human body, often in connection with biblical scenes. Disembodiment is not an option for those who believe that human beings are created in God’s image with beautiful bodies, that everything from sin to salvation are embodied experiences, and that God’s redemption comes through the broken and risen body of Jesus. The paintings of Edward Knippers invite us to consider the goodness, brokenness, mystery, and glory of Christ’s body as well our own, urging us to grapple with the temptation to avoid, sexualize, downplay, or disparage bodies along with a fully embodied faith.”

I signed up! The early-bird discount is $20 off and ends March 1.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Give Me a Clean Heart” by Margaret Douroux, sung by Everett Harris and friends: Written in 1970 by Dr. Margaret Pleasant Douroux, this song of penitence based on Psalm 51:10 is a gospel classic. In the 2020 video below, it’s sung a cappella by a six-person virtual choir, using an arrangement by Adoration ’N Prayze. To hear it sung in a Black church context, led by Rev. Dr. E. Dewey Smith Jr., click here.

>> “Psalm 50” (Psalm 51) in Aramaic by Seraphim Bit-Kharibi: Father Seraphim Bit-Kharibi is an Assyrian Orthodox monk who is the archimandrite (head) of the Monastery of the Thirteen Holy Assyrian Fathers in Dzwell Kanda, Georgia. He is Assyrian by ethnicity, and his native language is Aramaic, the language of Jesus. Here he chants Psalm 51 (Psalm 50 in the Greek numbering system) in Aramaic with his church choir, which appears on his 2018 album Chanting in the Language of Christ. In the following video, the singing starts fifty-one seconds in.

There is also a video recording of him chanting this psalm with a young unidentified girl during the visit of Pope Francis to Georgia on September 30, 2016.

In a 2014 interview, Father Seraphim said:

My people, Assyrians, . . . still pay with their lives for their worship of Christ. In Eastern countries such as Iraq, Iran, Syria, and other warzones, Assyrians get attacked in their churches and beheaded if they refuse to convert to Islam. They are being destroyed en masse.

As for Assyrians in Georgia, there are about 4,000 of them. The Assyrian language is basically Neo-Aramaic, which is about 2,500 years old. The wonderful thing is that this language allows us insight into what people living centuries ago sounded like. Out of 4,000 Assyrians living in Georgia, 2,000 of them live in my village of Kanda and comprise 95 percent of its population. Almost 90 percent of these people speak Neo-Aramaic.

+++

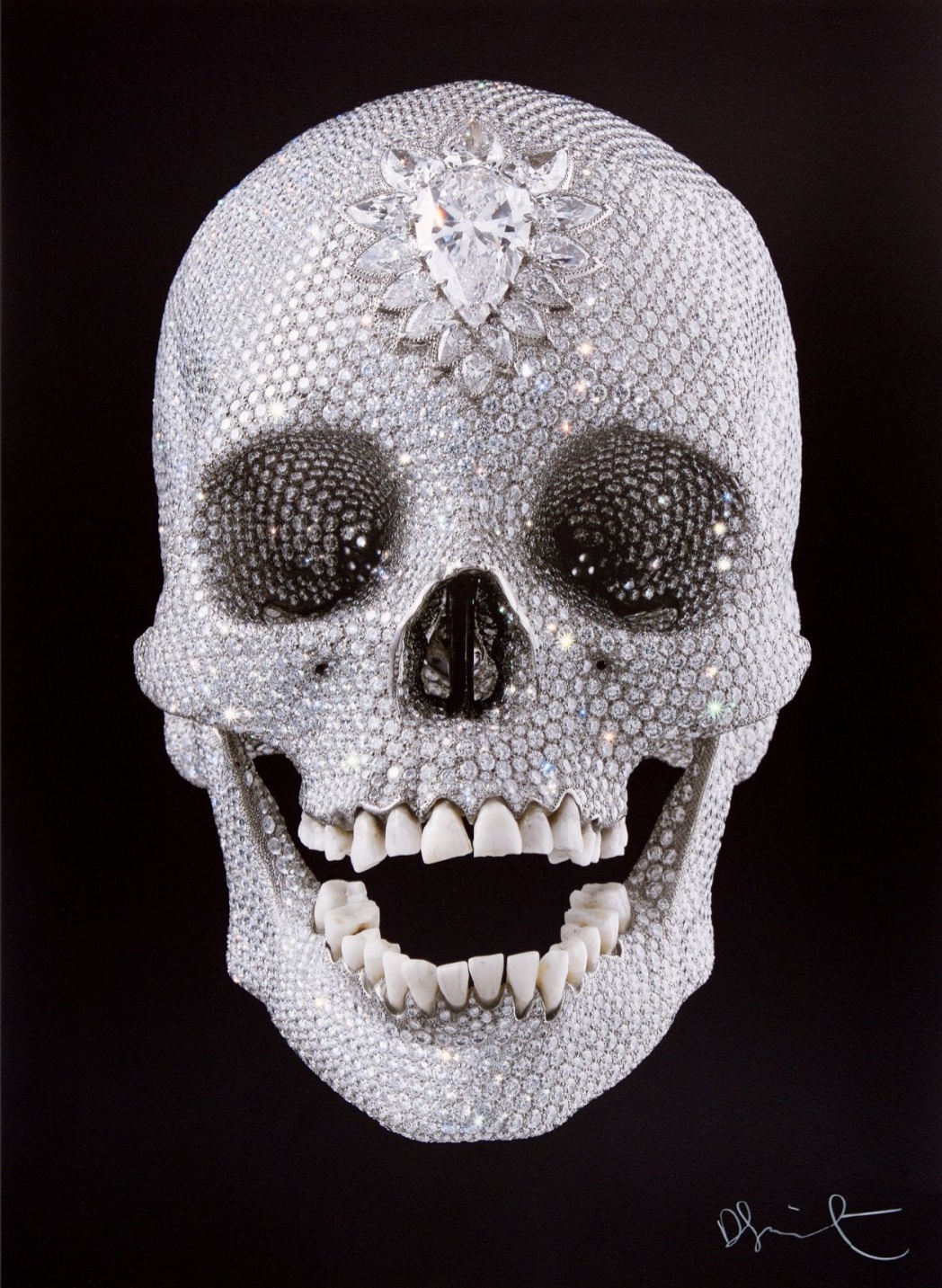

ART COMMENTARIES: Lent Stations: Vices and Virtues: To promote art-driven contemplation around Lenten themes, this Lent the Visual Commentary on Scripture is spotlighting fourteen artworks from its archives based on the seven deadly sins and seven virtues. So far they’ve featured a pair of medieval statues personifying the Synagogue and the Church, a diamond-encrusted skull by Damien Hirst, a Rubens painting of Cain murdering Abel, and an Egyptian textile roundel depicting scenes from the life of Joseph.