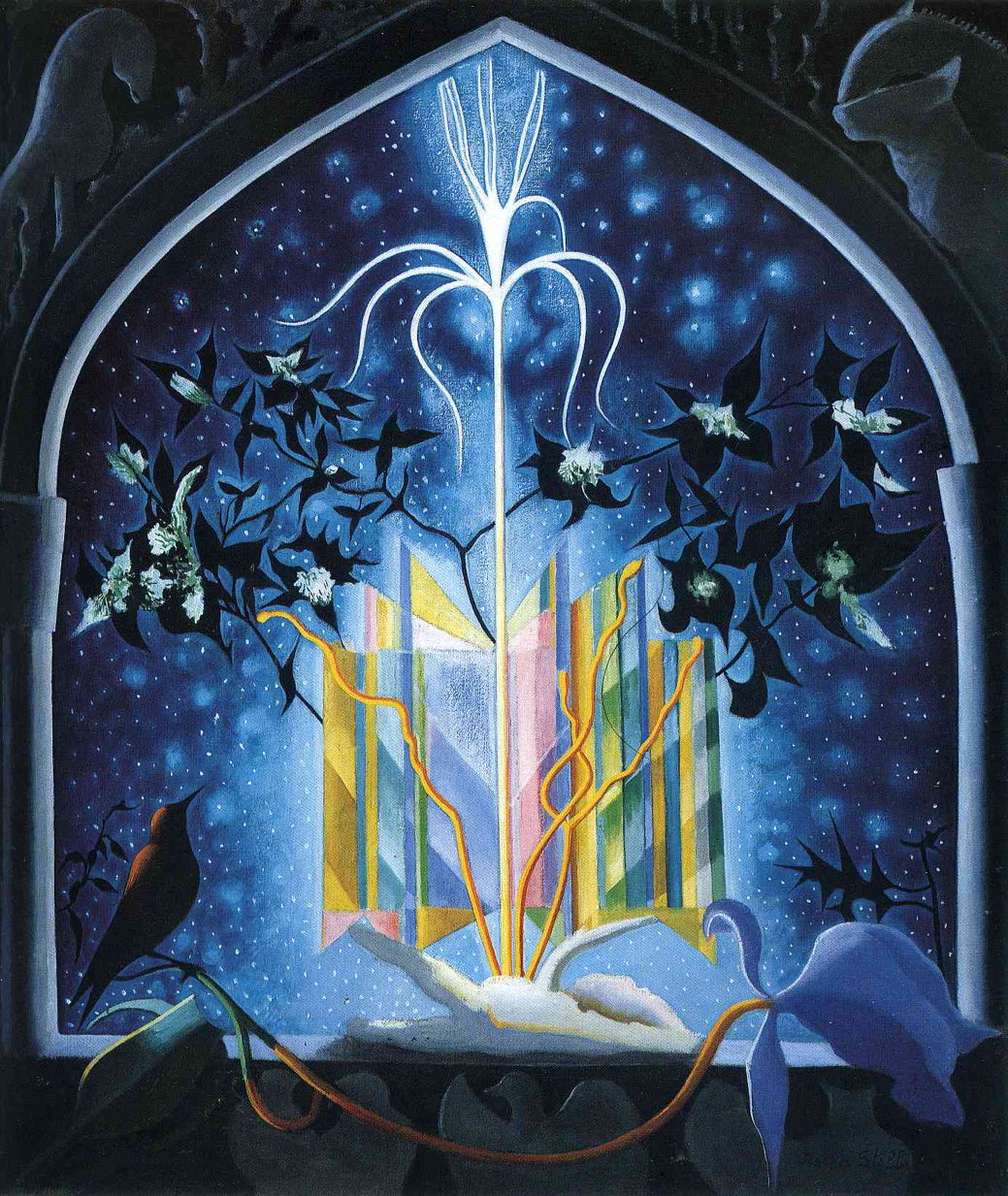

LOOK: Serenade: A Christmas Fantasy by Joseph Stella

Joseph Stella (1877–1946) [previously] was an Italian American painter who became an important figure in modern art. His Serenade: A Christmas Fantasy is not overtly religious, but it does incorporate a few elements traditionally associated with Christmastime—a starry night sky, a holly branch, an ox and ass, a dove—and has a mystical quality. In the center, a flower emerges from what appears to be a conch shell, its pistil and stamen glowing. The flower’s stem shoots up past an abstract, mobile-like object that could be shards of colorful glass or pieces of cut paper. It’s a visionary composition that is open to multiple readings.

Art historian Judith Zilczer comments on the painting in the exhibition catalog Joseph Stella: The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection (Smithsonian Institution, 1983):

Serenade: A Christmas Fantasy typifies Stella’s mature symbolist style. Framed by an arch, a fantastic tree form bisects the composition and serves as the central image of the painting. The colors of the iridescent prism surrounding the central axis recall the abstract geometric style of Stella’s Futurist canvases.

The meaning of Stella’s complex imagery remains elusive. The ox and ass in the upper right spandrel traditionally appear together in paintings of the Nativity. The image of the dove in the center of the lower border is the symbol of the Holy Ghost. These Christian symbols are consistent with the painting’s subtitle, A Christmas Fantasy. The painting is also known as The Fountain (La Fontaine). The treelike form in the center may represent an abstraction of a jet of water. The image of the fountain often served as an attribute of the Virgin Mary, who was regarded as the “fountain of living waters.” It is possible that in this canvas Stella has fused the image of the tree of life with the fountain as the symbol of the Virgin. The nightingale perched on the tendril [of the purple iris] in the lower left is the source of the serenade. (54)

I see in Serenade the promise of Advent—light emerging out of darkness, wondrous new life growing out of dormancy. There’s a coming fullness here, a blossoming. The chromatic spectrum refracted by the center object evokes a rainbow, the sign of God’s covenant with all living creatures in Genesis 9.

LISTEN: “Wonder” by MaMuse (Sarah Nutting and Karisha Longaker), on Prayers for Freedom (2018)

Oooh, I wonder

Oooh, I wonder

Oooh, I wonder

What is to come out of this darknessI’ve been moving, moving, moving, moving through the darkness

Moving, moving, moving, moving through the darkness

Moving, moving, moving, moving through the darkness

I wonder when the light is cracking openOooh, I wonder

Oooh, I am filled with wonder

Oooh, I wonder

What is to come out of this darknessI thought this candle had long gone out

I thought this candle had long gone out

I thought that it had long gone out

But today, today, today, today I can see

There’s still a flickering, flickeringOooh, I wonder

Oooh, I wonder

Oooh, I wonder

What is to come out of this darknessBurn, burn, burn, burning on the inside

Burn, burn, burn, burning like a bright light

Burn, burn, burn, burning on the inside

This light’s still burning, burning brightI thought this candle had long gone out

I thought that it was long gone out

I thought that this candle had long gone out

But today, today, today, today I can see

There’s more than a flickeringOooh, I wonder

Oooh, I am filled with wonder

Oooh, I wonder

What is to come out of this darkness

This song was written by MaMuse [previously], an acoustic folk duo who I’d say are “spiritual but not religious,” several years ago on the winter solstice. Watch a live video recording from January 2019 at the Chico Women’s Club in Chico, California, the two’s hometown.

Advent is sometimes mischaracterized as glum, but actually, joyfulness is a key aspect of the season. There’s a somberness, for sure, but it’s married with excitement for what’s coming.

I hope to capture this dual tone of Advent in my selection of art and music over the next twenty-four days. This is the first post in a daily series that will run to the end of Advent on December 24, and then for the duration of Christmas, from December 25 to January 6. Many of the songs in the series can be listened to on the Art & Theology Advent Playlist, Christmastide Playlist, and Epiphany Playlist on Spotify.

In the liturgical calendar, Advent-Christmas-Epiphany is known as the cycle of light. Many churches and families light candles around an Advent wreath, progressively more until Christmas, symbolizing the Light of the World getting nearer, dispelling more of the darkness.

May you be blessed this Advent season as you wonder and explore what is to come out of December’s darkness. May you discern with delight those places where “the light is cracking open,” where God is shining through.