The doctrine of the imago Dei—which states that human beings were uniquely created in the image of God and continue to bear that image—is central to Christian theology, for it tells us who (and Whose) we are. The book The Image of God in an Image Driven Age: Explorations in Theological Anthropology (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2016), edited by Beth Felker Jones and Jeffrey W. Barbeau, delves into that doctrine, examining its implications for relationships, ethics, sexuality, consumer visual culture, art making, dissemination of the gospel, and more. Comprising twelve essays that resulted from the 2015 Wheaton Theology Conference, the book explores what it means to be made in God’s image and issues a challenge: that we resist all the false images that try to topple the one true image in our lives.

The doctrine of the imago Dei—which states that human beings were uniquely created in the image of God and continue to bear that image—is central to Christian theology, for it tells us who (and Whose) we are. The book The Image of God in an Image Driven Age: Explorations in Theological Anthropology (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2016), edited by Beth Felker Jones and Jeffrey W. Barbeau, delves into that doctrine, examining its implications for relationships, ethics, sexuality, consumer visual culture, art making, dissemination of the gospel, and more. Comprising twelve essays that resulted from the 2015 Wheaton Theology Conference, the book explores what it means to be made in God’s image and issues a challenge: that we resist all the false images that try to topple the one true image in our lives.

Two of the chapters revolve around visual images. In chapter 5, “Culture Breaking: In Praise of Iconoclasm,” Matthew J. Milliner starts out by stating that we live in an optocracy—that is, we are ruled by what our eyes see. Advertisements (billboards, commercials, magazines, web banners), celebrity coverage, and product packaging and store displays are high up on the throne, and we think and act according to their influence.

To illustrate the takeover of unedifying imagery, he cites Limelight Shops, a mini-mall in New York City that inhabits the deconsecrated Church of the Holy Communion. Where a Christian community once thrived, signage and shop displays now parody Christianity, beckoning shoppers to “be transformed,” to try on True Religion jeans in confession-booth dressing rooms, and to indulge in a “slice of heaven” at the pizzeria.

Milliner calls for opposition to the deleterious aspects of our optocracy, a reclamation of our iconoclastic heritage (which, he notes later with examples, belongs to all three branches of Christianity, not just Protestantism):

Evangelicals have spent the last half of the century embarrassed of their iconoclastic heritage and attempting to make themselves culturally serious. But the challenge that is so clear in the case of Limelight Shops might spur us to reactivate our iconoclastic heritage as well. Our charge may be not only to go about culture making but to do some culture breaking as well, for breaking is what the people of God do when they find themselves in Babylon. (112)

He endorses not a literal breaking but a mental and rhetorical breaking, much as the Israelites did when they were in Babylon (e.g., Jeremiah 10:5). We need to break the power certain images hold over us, say no to their attempts to shape and define us. God alone can tell us who we truly are, and we bear his imprint.

Many contemporary artists in the macro–art world would claim to share Milliner’s iconoclastic impulse, but in practice, most of them fail to effectively break anything, and Milliner gives a few examples of those failures. Then he recounts several successes from within his own immediate sphere: works by his art faculty colleagues at Wheaton College. Among the commendable works he discusses are Jeremy Botts’s Bee in Hand; Greg Halvorsen Schreck’s Lambertian photograph The Shroud and his American Trinity and the Cry of the Deer (I covered Botts’s and Schreck’s Via Dolorosa cycle in February); David J. P. Hooker’s Corpus (pictured on the book’s cover); and Joel Sheesley’s Camels and his Good Shepherd mural at the local All Souls Anglican Church—all of which are reproduced as halftones in the book. These artists demonstrate different ways to break by making and vice versa—to engage in “creative destruction,” as Philip Jenkins puts it in the final chapter (259).

Milliner is one of my favorite voices in the art and theology conversation. (I engaged with his talk “God in the Modern Wing” on my former blog.) Follow him at millinerd.com and/or @millinerd.

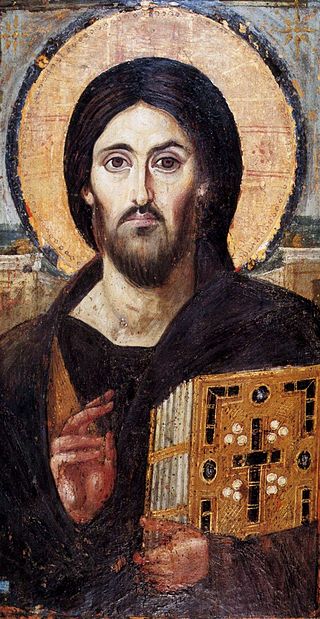

Chapter 7, “What Does It Mean to See Someone? Icons and Identity” by Ian A. McFarland, explains the theology of icons in Eastern churches, tracing the historical development of icon veneration and highlighting key historical arguments in its defense. His thesis:

The chief significance of icons is missed if the emphasis on their depiction of glorified humanity eclipses their role in helping us to see each other here and now. Specifically, icons clarify what it means to speak of human beings as created in the image of God. (158)

Icon veneration, he claims, is a practice whereby we acknowledge the personhood of Jesus and the saints, both dead and living, as well as our own personhood. Spending time with icons trains us to see people rightly, helping us avoid the opposite errors of materialism (the idea that we are only bodies) and dualism (the idea that body is separable from spirit).

One of the more provocative sections of this chapter is the teasing out of Theodore the Studite’s claim that Christ “would lose his humanity, if He were not seen and venerated through the production of an image” (qtd. 168). Bodily mediation, McFarland says, is necessary for us to know God and others:

The theology of icons implies that to presume to know God as other than incarnate is to presume to know God other than God in fact is, and thus to fail to know God at all. And because there is no knowing Jesus, the one true image of the invisible God, in abstraction from the body he assumed from Mary, we must confess that there is no knowledge of any human being, as one created in that image, apart from his body. (169)

A compelling statement, but one is left wondering whether icons are the only way to accomplish this knowing, as opposed to art in other styles and settings.

Drawing its title from the Dutch Calvinist word for the iconoclastic riots of the sixteenth-century, “The Storm of Images: The Image of God in Global Faith” (chapter 12) by Philip Jenkins touches on visual images of the divine but is more broadly about conceptual understandings of God and their dependency on culture. Christianity has been crossing cultural borders since its inception, and whenever it does, it has to adapt to local realities and frames of reference. Because Christianity’s center of gravity is moving to the global South, Christians in its former heartlands of North America and western Europe are confronted with diverse theologies that in some ways look different from our own. We must resist our tendency to casually dismiss them; we owe our fellow believers ear and not just voice.

It helps if we first recognize the contextualized nature of our own theologies. “The task for theologians in the modern world,” writes Jenkins, “is to strip away the Western accretions to recover a gospel in its natural social setting. Put another way, we are, in our specific culture and cultures, made in God’s image” (253).

Jenkins leads us in this task of peeling away with several examples that expose culturally determined readings of the gospel in Western churches. For example, Western interpretations of the atonement rely heavily on Anselm of Canterbury’s feudal model, which he developed based on the dominant social system of his time and place—medieval Europe.

He also gives examples of contextualization in non-Western cultures. In terms of visual art, he mentions the lotus-cross, which became the distinctive symbol of Christianity in Asia as early as the eighth century, when it was carved onto a “stone sutra” in Xian, China. (For more on this, see part 3 of my ten-part series on a collection of seventh- and eighth-century Chinese Christian sacred texts known as the Jesus Sutras.) For Buddhists, the lotus symbolizes spiritual perfection, which is why the Buddha is often portrayed as sitting on one.

Jenkins also cites the cult of the Virgin in Latin America and the Philippines, which from the sixteenth century has imagined the Virgin in local or native guise, commonly with non-European skin tones.

As Christianity continues to spread, and with it the imago Dei doctrine, people around the world who have been treated as less than human find a revolutionary new notion of human dignity.

Jenkins has an optimistic perspective on new images of God in emerging Christian societies, but he also acknowledges their potential dangers. He does not here seek to navigate the sticky issue of how to distinguish between images and idols, between accommodation and syncretism. (That would require a much lengthier treatment.) But he does offer some advice:

The best contribution that older churches can make to rising communities is in sharing their accumulated experiences and understandings. They can share their gallery of images of the divine, assessing those that have posed dangers and those that have proved most fruitful. Before beginning such an enterprise, those world-weary Euro-American churches need first to rediscover their own histories and understand those images. They need, above all, to appreciate which are honest attempts to view the face of God and which are mere projections. (258–59)

In other words, we need to critically examine our own images of God—physical and mental—before we do so with those of other peoples.

This chapter concludes on a similar note as Milliner’s. Jenkins says that throughout the ages, new images of the divine will continue to be erected in individual minds and communities. Some of those images will endure, and others will be smashed. Not all images are good, but neither are they all bad. Whether we’re the ones doing the erecting or the smashing, we need discernment.

—–

The first three chapters address all the biblical passages that deal with the imago Dei doctrine and outline different interpretations. In her exegesis of Genesis 1:26–27, Catherine McDowell explains how “humanity is defined both as God’s royal ‘son’ and as living ‘statuettes’ representing God and his rule in his macro-temple, the world” (42). William A. Dyrness looks at how this definition, this image, was tainted by the fall. Craig L. Blomberg, who understands the image as the capacity for moral behavior and accountability, discusses the progressive (in the here and now) and then perfect (in the hereafter) restoration of the image, especially in regard to the work of Christ.

Chapter 4, “Uncovering Christ,” discusses sexuality as an aspect of God’s image but is, I feel, underdeveloped. Timothy R. Gaines and Shawna Songer Gaines make some bold statements that go unexplained, things like the image of God is sexed, and sexual images can be used for holy purposes, and Jesus is a sexual being, and “sexuality finds its fullest expression in the incarnation of Christ” (96). How did Jesus express his sexuality? Is it possible to do so without a sex act? The authors seem to conflate several terms with sexuality, like nakedness, touch, and desire, when really these are only subsets, not synonyms; all three can be nonsexual, and in the authors’ uses of the terms—e.g., touching during the liturgical passing of the peace, or desiring God—they often are. The lack of working definitions makes the chapter confusing.

One compelling portion was the explanation of the theology behind Renaissance depictions of a nude Christ. The Gaineses cite Montagna’s Holy Family, which shows the Christ child lifting his tunic to expose his genitalia, and Michelangelo’s Risen Christ, which originally showed the adult Christ fully nude (the custodians of the sculpture later added a bronze loincloth out of modesty).

Working within a wider Renaissance tradition, the artists of these works aimed not to shock but to show that Christ frees human nature from the shame caused by the fall. Our humanity, of which are bodies are one part, is good and nothing to be embarrassed about.

But again, I don’t think of these as sexual images. They show (or did show) a penis but aren’t meant to stir erotic desire. So there’s a bit of a disconnect between the authors’ thesis and these examples. Maybe if rather than sexuality the chapter had focused on flesh or embodiedness, it could have been stronger. Granted, this was the hardest topic of them all.

In chapter 6 Christina Bieber Lake reflects theologically on Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, showing the persistence of the image of God through the darkness of despair, tragedy, and hopelessness.

In chapter 8 Daniela C. Augustine discusses the Spirit’s work in sanctifying image-bearing human beings. She draws a distinction between image (something we already have) and likeness (something we’re growing into).

In chapter 9 Janet Soskice sketches the relationship between the imago Dei in Genesis, which is universal and explicitly tied to respect accord to human beings, and the imago Dei as conceived by Paul, which is directed toward cosmology, eschatology, and spirituality. The common thread, she concludes, is that no one individual can image God; it is only collectively that we can do that.

In chapter 10 Soong-Chan Rah considers the racialization of the image of God. Challenging assumptions of white superiority, he shows that the norm for being human is not found in whiteness. He discusses the role of the National Black Evangelical Association in facilitating the rise of a unique black evangelical identity in America. He concludes,

The image of God must be recognized in all races and cultures and evidenced in denominational leadership, seminary faculty, Christian conferences and the authorship of books. The dysfunctional theological imagination must be challenged with a presentation of authoritative spiritual voices that reflect the fullness of the image of God. (224)

In chapter 11 Beth Felker Jones explores how the imago Dei offers resistance to commodification. She writes, “All Christians—universally and particularly—are called to witness to that resistance by rejoicing in the freedom of our bodies from the market and by rebelling wherever that liberty is denied” (232). Because human beings are image bearers, Christians oppose slavery and prostitution, for example, and also the more subtle commodification at play in the market’s insistence that we need to purchase our identities by buying brand-name products.

+++

I appreciate The Image of God’s contribution to the field of theological anthropology. It approaches the question of what it means to be human from a variety of angles and voices, providing a rich survey of this doctrinal landscape of the imago Dei and showing ways it should impact our witness in the world.

Video-recorded presentations of earlier versions of these essays can be found on YouTube.