I spent last week in New Mexico with my husband, Eric, and my in-laws, visiting relatives in the south, then driving up north to spend some time in Albuquerque and Santa Fe. It was my first time to the Southwest, to the state where Eric was born; his grandparents came over from Mexico as teenagers and settled in Hobbs, a small oil town, and his mom grew up there, learning English in school. I enjoyed all the tastes: spicy green chiles in or on just about everything (eggs, tacos, burgers, soup, corn, French fries); piñons (pine nuts) galore sprinkled alongside dusty footpaths, ready to crack open and eat; and sopapillas (pillow-shaped fried dough drizzled with honey) after every meal.

On the five-hour upstate drive, the blue sky spread wide open across the desert and clouds hung low, casting shadows that, from the car, looked like bodies of water. The way was flat, flat, flat—until we reached Santa Fe, where mountains rose up and aspens flickered their glorious gold.

In Albuquerque we went to the International Balloon Fiesta, where hundreds of hot-air balloonists come out once a year to fly. Unfortunately, high winds prevented the “mass ascension” from happening the day we were there, but we saw static displays—inflated balloons in all shapes and colors. (My father-in-law was partial to the Darth Vader balloon; I liked the lovebirds.) And I got to visit to the artisan tent, where I bought my first nativity set! It’s seven pieces in clay by New Mexico native Barbara Boyd. I set it up in our living room when I got home, but Eric says I need to put it away until Advent . . .

We spent an afternoon in Old Town Albuquerque, strolling past historic adobe buildings and into galleries, while street musicians—Native American flautists and mariachi bands, mostly—provided a culturally immersive soundtrack. Our first stop happened to be one of my favorites: John Isaac Antiques and Folk Art. Isaac has a beautiful collection of santos (Hispano Catholic religious images)—a whole roomful—both contemporary and from the last few centuries. I was close to buying a Saint Francis bulto by Ben Ortega (Francis was his hallmark) but decided against it, and now I wish I hadn’t. Nonbuyer’s remorse—ugh.

Just before we left Old Town, my mother-in-law suggested one last gallery: Santisima, owned by Johnny Salas. I immediately recognized the work of Albuquerque native Brandon Maldonado, which is heavily influenced by the tradition of Día de los Muertos. I’m really attracted to Day of the Dead imagery, with all its macabre whimsy—the kind that makes most Protestants feel uncomfortable. I think the draw, for me, is that it embraces death instead of shrinking away from it; it says, “Death, we do not fear you.” As Maldonado says, Day of the Dead is not meant to be frightful but rather mocking, in a way:

The masses may prefer to think of the deceased as haloed angels floating on fluffy white clouds, but I like the idea of dancing skeletons in hats!

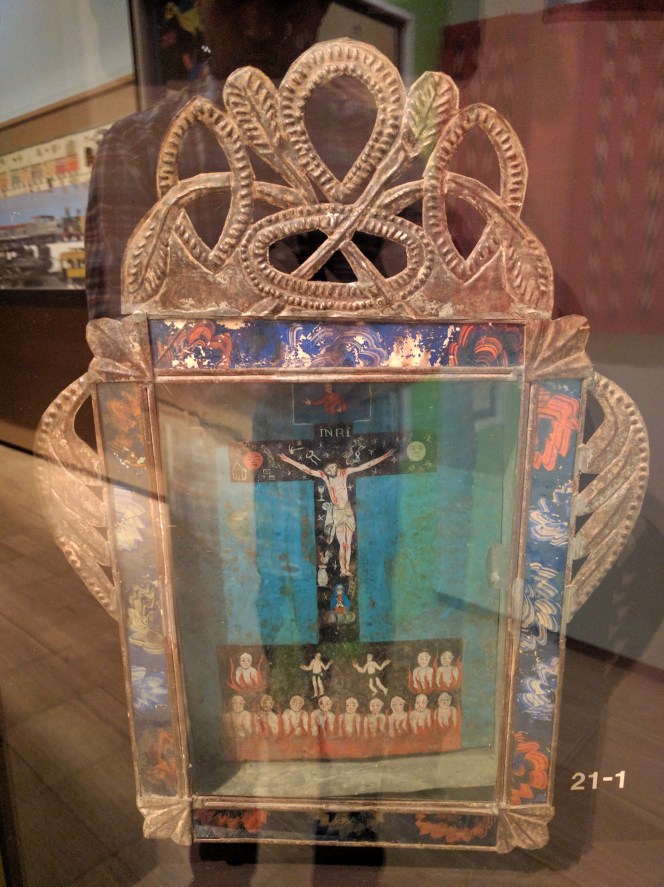

At Santisima I was introduced to the work of the young santero Vicente Telles, also a native of Albuquerque. I really liked his Adam and Eve and Saint Pelagia retablos but most especially his Crucifixion one, which I ended up buying.

It shows a curtain opening up, and two chandeliers dangling, to present Christ on the cross, given for us. As is traditional in New Mexican art, his shoulders and knees are bloodied; in Telles’s interpretation, the blood marks Christ in patterns, almost like tattoos. The animas solas (lonely souls) in the flames of purgatory is also a common motif in New Mexican art. I do not personally subscribe to the doctrine of purgatory, so I read the souls, rather, as Adam and Eve awaiting redemption. According to church tradition, Golgotha was the site not only of Christ’s execution but also of Adam’s burial, which is why, since the Middle Ages, a skull is often painted at the cross’s base, emphasizing Christ’s role as the Second Adam. Telles shows Eve reaching out to touch this death-symbol, lamenting her and Adam’s primordial rebellion and pleading in faith, with her eyes, for deliverance from its consequences. This is the precursor to the Anastasis (Resurrection) icon of Eastern Orthodoxy, which shows Jesus breaking down the doors of Sheol and pulling Adam and Eve up out of their graves to be with him in heaven. We are dead in our sins until Christ raises us. His spilled blood has “loosed the pains of death” once and for all.

To give the retablo a glistening appearance, Telles applied a micaceous clay slip to the pinewood before applying the paint.

If you’re not able to see Telles’s art in person at Santisima (he’s sold exclusively there), visit his Facebook page.

In Santa Fe there was a lot more art to see on Canyon Road. Both my father-in-law and I really liked a bronze pot at Canyon Fine Art by Isleta Pueblo artist Caroline Carpio, called River of Life II; the “river” is a sinuous band of turquoise stone—beautiful.

I was thrilled to stumble upon a wall of Chagall lithographs at the Matthews Gallery—and to be told, for the first time, that photos were allowed!

Gallery owner Linda Matthews showed me to another Jewish artist, whose style was obviously influenced by Chagall: Theo Tobiasse. Tobiasse was born in Israel to Lithuanian parents but relocated to Paris as a child, where he was forced into hiding during the Nazi occupation. He painted, among other things, biblical subjects and Jewish life. His Rabbi Dancing with the Torah was on display at the gallery, and more of his works are available for sale on the gallery website.

I also learned of the work of local artist Alfred Morang, “a visual diary of Santa Fe in the 1940s and 1950s,” including its religious culture—churches, mountainside crosses, Penitente rituals. Postimpressionistic, his canvases are painted thickly with a palette knife.

A short walk from Canyon Road is the Santa Fe Plaza, where stands the nineteenth-century Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. It’s home to a gorgeous “saints of the Americas” reredos by Robert Lentz, which I wish I could have gotten a closer look at and a better photo of. The section was roped off to create space for a professional crew to photograph the 1717 Francis statue, which was temporarily taken down from its center niche.

The bottom center panel of the reredos features a likeness of St. Kateri Tekakwitha, “Lily of the Mohawks,” the first Native American to be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. (There’s a monumental bronze statue of her just outside the church entrance.) She was known, in the words of contemporary biographer Claude Chauchetière, for her “charity, industry, purity, and fortitude.” Lentz shows her with a basket of corn in her hands and a turtle at her feet.

You can hear Lentz discuss the reredos and view details of it in the following video:

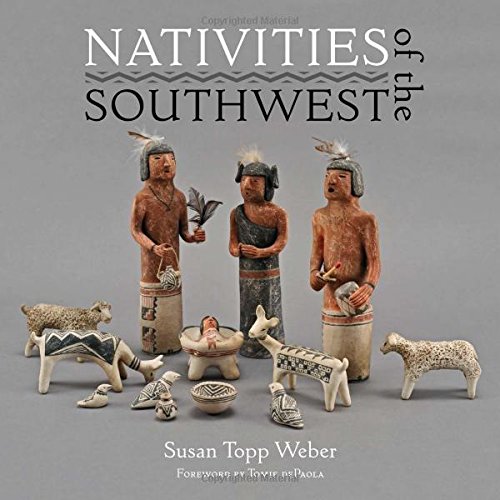

In the church gift shop I bought a book that made a fantastic companion on our drive back to Hobbs: Nativities of the Southwest by Susan Topp Weber, owner of Susan’s Christmas Shop in Santa Fe. It reproduces, in color, photos of ninety-five nativities by Pueblo, Navajo, Tohono O’odham, and New Mexico Spanish and Anglo artists. In a Cochiti nativity by Helen Cordero, baby Jesus rests on a sheepskin bed, while a hunter brings, as a gift, rabbits from the kill and Pueblo women bring pottery, corn, and oven bread. Another nativity—by Santana Seonia—takes place inside a kiva, a Pueblo ceremonial chamber. Once I got home I immediately purchased the companion volume, Nativities of the World.

One of our other art stops in Santa Fe was the Museum of International Folk Art. A temporary exhibition called “Sacred Realm: Blessings and Good Fortune Across Asia” was on display in the Cotsen Gallery, showcasing sacred objects from the five major world religions, which all originated in Asia. My two favorite Christian pieces were a silver cross from Jordan picturing the baptism of Christ

and a hmayil (illuminated Armenian prayer scroll).

Designed for portability, hmayil typically contain prayers and miracle stories and illustrations of saints’ lives and the life of Christ. The text may be written in a talismanic pattern to increase its efficacy. According to the museum wall text,

Prayers included in this hmayil are the Prayer of Saint Cyprian and the Prayer against All Evil (shown), written in red and black inks in an uncharacteristic chain pattern (they are usually zig-zag). Illustrated saints include the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, Saint Yustiana (Justina), and a portrait of Jesus Christ in the center of a six-pointed star that may represent the Holy Trinity. . . .

The Armenian Church, a branch of the Eastern Orthodox Church, dates back to the first century CE when early apostles brought Christianity to Armenia. Armenia established Christianity as its official religion by the fourth century CE. Armenians have lived in Jerusalem since that time, as Armenian monks began to settle in the Holy City.

The primary, permanent exhibition space is an enormous room with cases, tables, and shelves displaying more than ten thousand objects from one hundred-plus countries. They weren’t always organized by date, region, or theme, and the lack of nearby credit and explanatory info (which, if available, had to be looked up in a booklet) made the experience all the more overwhelming—but boy, what a feast for the eyes and spirit!

I gravitated first to the santos. There were several Crucifixion images, and they share many of the same elements: sun and moon on the crossbar, Adam and Eve in the Garden at the bottom, Saint Michael the Archangel holding the scales of justice, souls in purgatory praying for release, the Virgin Mary pierced by a sword (in fulfillment of Simeon’s prophecy), and lots of blood. Assuming I decoded the numbers correctly, these three are from nineteenth-century Mexico:

Speaking of blood, there’s this tin retablo of La Mano Poderosa de Dios (“The Mighty Hand of God”) spurting a stream of it into a fountain, which the sheep (that’s us!) in turn drink from straws:

Apparently it’s a common subject.

Here’s some other Christian folk art that struck my fancy:

There were also a few Trees of Life from central Mexico, but they were placed high up, so I wasn’t at a good angle to photograph them.

The Museum of Spanish Colonial Art is a hop, skip, and a jump away from the folk art museum, situated on the same Museum Hill. It’s much smaller, but it majors in religious art.

One of the museum’s newest acquisitions is a large-scale replica of the retablo mayor (main altar screen) at the Santuario de Chimayó, a historic adobe church thirty miles north of Santa Fe that’s the most popular pilgrimage site in the United States. The sheaves of wheat and cluster of grapes that flank Christ allude to his body and blood, which Christians partake of in the Eucharist.

The MoSCA commissioned this piece from Spanish Market artist Franque Zamora earlier this year, and they have a smaller version on loan from the collection of Frank and Grace Servas.

I appreciated getting to see a Trinity retablo. As is typical in Spanish colonial iconography, three identical-looking men with triangular halos sit side-by-side, each holding a symbol particular to his person: a sun (Father), a lamb (Son), and a dove (Holy Spirit).

I also liked the wooden cross with straw inlays by Paula Rodriguez. It depicts, from top to bottom, Our Lady of San Juan de los Lagos, St. Francis, two angels, San Miguel, San Acacio, San Ysidro Labrador, and St. Joseph. On the crossbar, from left to right, is the Santo Niño de Atocha, two persons praying before a retablo of the Virgin, Bernardo Abeyta and the apparition of Nuestro Señor de Esquipulas, two persons at the well of healing mud, and the Santuario de Chimayó.

And the Youth Gallery, featuring work by children who are serious about art and craft, is impressive. The wooden nativity by Roberto Barela—age fourteen at the time—was a standout to me.

Lastly, I was blessed by the chance to meet Glen Strock, a pastor and artist who has lived in the area since 1979. I came across a painting of his in an arts and lectionary resource a few years ago (see below) and, remembering that he lived outside Santa Fe, decided to reach out. Even though he’s in the middle of a move and refurbishments, he graciously invited me into his home and took the time to show me some of his artwork and share with me some of his ministry goals.

Glen is the pastor of Pecos Valley Cowboy Church, part of the cowboy church movement to reach a demographic that’s typically put off by traditional church culture. In addition to answering this call, he has also answered the call to “unleash [his] inner artist.” After graduating from art school, he served as art director at the Museum of New Mexico Press, and for decades he has illustrated books on Southwest and Latin American culture—most popularly The People’s Guide to Mexico, which is still in print after forty-four years! (He lived in Mexico during the Vietnam War; although his father was a well-decorated Army veteran and his three brothers enlisted, he said the military was “not for [him].”)

Glen has an extensive knowledge of local history and a thorough love of the different cultures that reside in his home state, which he honors by giving attention and care to his commissions from publishers to visualize their histories and myths. I enjoyed seeing a lot of the gouaches that became the pages of El Agua, el Sol y la Luna, a Nigerian flood story retold in Spanish and given a Latin American aesthetic. He also talked me through his lovely cover illustration for Four Square Leagues: Pueblo Indian Land in New Mexico.

His noncommissioned work includes paintings of farms, truckfuls of “Christmas” (red and green) chiles, lowriders, kachinas (Pueblo tricksters), his children (sometimes represented literally, sometimes as animals), and biblical subjects—most recently, Jesus asleep in the boat during the storm, which is in its underpainting phase. He explained to me his attention to the net, which to him represents the network of relationships that was being woven among the disciples. In the first miraculous catch of fish (Luke 5:1–11), the net broke: the relationships were not yet strong enough, not as tightly bound. But after Jesus’s resurrection, the net was able to hold in all the fish (John 21:1–14), because the disciples had finally learned to love. Blessed be the ties that bind.

Glen is such a kind, humble man with a heart for hospitality and mission. He works from a much different context than the santeros—for one, he’s Protestant—and it was neat to hear about his plans for his family’s new house, where he hopes to regularly host missionaries, and for his church, which he wants to transition into a house church model. His move was prompted by the new management of Glorieta Conference Center, where he and his wife own a house on leased land and homeschool four of their five children; he and the sixty or so other families who have houses on the property were told they need to “surrender them,” as Glen put it. (They’ll be paid, but not fair market value.) Glen sought mediation, but to no avail. Despite losing a home that he has invested money and memories in, Glen has kept a positive attitude and harbors no bitterness; he’s trying to think like Joseph, he said. My very best wishes go out to him and his family as they set down roots in a new neighborhood and continue to preach, teach, love, and paint.

***

So there you have it—a summary of the art adventures my family and I went on last week. I had done a little research on santos before my trip to familiarize myself with the tradition, but the visit really stoked my desire to see and learn more. Maybe there’s a second trip to New Mexico in my future, which will have to include time in Taos and Chimayó.

[…] (Related post: “Religious art highlights from New Mexico”) […]

LikeLike

[…] (Related posts: “Flamenco-style devotional singing in southern Spain”; “Religious art highlights from New Mexico”) […]

LikeLike

[…] regarded classic santero from early New Mexico, so I was already familiar with his work (note the visual influences on contemporary santero Vicente Telles, one of whose Crucifixion retablos I own). The chandeliers in Aragón’s painting are like those found in the chancels of New Mexico […]

LikeLike

[…] This year I bought a little plastic dragon myself to add to my household nativity! Below are some images my husband and I took. The clay figurines and adobe-style backdrop were made by Barbara Boyd, an artisan from New Mexico. (I bought them in 2016 at a festival in Albuquerque.) […]

LikeLike