A staple of English literature curricula, George Herbert (1593–1633) is one of the best religious poets of any era. Born in Wales, he studied rhetoric at Cambridge University, becoming fluent in Latin and Greek and beginning an avocation of writing verse. After a short career in oration and then politics, he shifted courses to become a pastor. He was appointed to a small rural parish near Salisbury, where he served for only three years before contracting tuberculosis at age thirty-nine. On his deathbed he gave his friend Nicholas Ferrar a manuscript of all the poems he had written throughout his life, telling him to publish it if he thought it might “turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul,” and if not, to “burn it; for I and it are less than the least of God’s mercies.” Thankfully, Ferrar chose the former, and The Temple was published posthumously in 1633. It has been in print continuously ever since.

One of the poems from this volume is “The Agony,” a meditation on the suffering that Christ bore out of love for humanity. Below I will walk through it stanza by stanza, and then I will present a new partial musical setting of it that makes intertextual connections with scripture. I will conclude by sharing a once-popular artistic motif, the mystic winepress, that visualizes one of Herbert’s metaphors (a metaphor developed by early theologians, such as Augustine and Gregory the Great).

“The Agony” by George Herbert

Philosophers have measured mountains,

Fathomed the depths of seas, of states and kings;

Walked with a staff to heav’n, and traced fountains:

But there are two vast, spacious things,

The which to measure it doth more behove;

Yet few there are that sound them—Sin and Love.Who would know Sin, let him repair

Unto Mount Olivet; there shall he see

A Man so wrung with pains, that all His hair,

His skin, His garments bloody be.

Sin is that press and vice, which forceth pain

To hunt his cruel food through ev’ry vein.Who knows not Love, let him assay

And taste that juice which, on the cross, a pike

Did set again abroach; then let him say

If ever he did taste the like,

Love is that liquor sweet and most divine,

Which my God feels as blood, but I as wine.

In the first stanza of “The Agony,” Herbert comments on man’s dogged pursuit of empirical knowledge. We develop tools for our trades, then use them to “measure,” “fathom,” and “trace”—to explore the heights and depths of our physical environments, the ins and outs of the world’s political systems. There’s nothing wrong with this per se, but we ought not to neglect the “two vast, spacious things” that are most worthy of exploration: sin and love. These truths, unlike others, are apprehended not by amassing and analyzing data but by simply beholding. To know sin, Herbert says, look to Gethsemane: see Christ crushed. To know love, look to the cross: see Christ pierced. See, and taste. The Lord is good.

Christ is literally at the center of the poem, in lines 9 and 10: “A Man so wrung with pains, that all His hair, / His skin, His garments bloody be.” In Gethsemane he feels the immense pressure of sin—it grips him like a vise, squeezes the blood out of him like a winepress. Herbert personifies pain as a predator stalking Jesus’s veins, feeding on his insides.

In the winepress metaphor Herbert draws on a longstanding tradition that interprets specific Old Testament passages in light of Christ. Take Isaiah 63:3a, for example: “I have trodden the winepress alone, and from the peoples no one was with me.” Though in context the grape-crusher is Yahweh and the grapes the enemies of Israel, the church fathers believed this verse foretold that Christ himself would be “crushed for our iniquities” (Isaiah 53:5) on the cross—pressed into wine for our sakes. In this reading the “lifeblood spattered on my garments” is Christ’s own blood, not others’, and Genesis 49:11b is likewise folded in: “he has washed his garments in wine and his vesture in the blood of grapes.” By acknowledging God’s wrath as redirected from sinful man onto the sinless Christ, these theologians reconceived the Isaianic symbol of the winepress as one of sacrifice and redemption, whereby divine love is expressed, in every sense of the word, and “enemies” are invited to come and drink.

In the third stanza of Herbert’s poem, Christ becomes a cask of wine who, when tapped (“set abroach”) by the Roman spear, issues forth a fine vintage for the refreshment of all. The closing couplet is one of Herbert’s most beautiful: “Love is that liquor sweet and most divine, / Which my God feels as blood, but I as wine.” What Christ experienced as bitter suffering, we experience as sweetness.

+++

Commissioned by the International Artist Initiative, “Blood of the Vine” by Alexandra T. Bryant is a musical composition for violin, viola, cello, trumpet, flute, voice, and wineglasses that interweaves excerpts from George Herbert’s poem “The Agony” with verses from the Gospel of Matthew and the book of Revelation. It premiered in Rochester, New York, on April 13, 2017 (Maundy Thursday).

Philosophers have measured mountains,

Have fathomed the depths of seas, of states, and kings . . .

But there are two vast, spacious things,

The which to measure it doth behoove,

Yet there, yet there are few that sound them:

Sin and Love.

Sin and Love.Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man.

He will dwell with them,

and they will be his people,

and God himself will be with them as their God. [Revelation 21:3]Who would know Sin, let him repair

Unto Mount Olivet; there shall he seeMy Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me;

nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will. [Matthew 26:39]A Man so wrung with pains, that all his hair,

His skin, his garments, bloody be.My Father, if this cannot pass unless I drink it,

your will be done. [Matthew 26:42]Sin is that press and vice, which forceth pain

To hunt his cruel food through every vein.Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth,

for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away,

and the sea was no more.

And I saw the holy city, Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God. [Revelation 21:1–2a]Who knows not Love, let him assay

He will wipe away every tear from their eyes . . . [Revelation 21:4a]

Love is that liquor sweet and most divine,

Which my God feels as blood; but I, as wine.

The piece opens with moaning—initiated by the strings, then mimicked by the voice, which rises and falls with an “ahhhh.” This wavering short-vowel sound continues in the first word, “phi-lo-so-phers,” where the “lo” (lä) is extended across several beats in alternating pitches.

At 6:29 a series of short, airy, percussive sounds from the flute signals a transition. In response to Herbert’s “Sin and Love,” a new textual source, John’s Apocalypse, enters to “sound the depths” of these two realities. God dwells with man! the scripture proclaims. On the other side of this verse’s musical setting there’s silence, a space to reflect for a moment on the beauty of the Incarnation, and its aim.

Then Herbert continues, inviting those who wish to confront sin to visit the Garden of Gethsemane, where you will see . . .

A curtain then opens to reveal a scene from Matthew’s passion narrative, and Christ’s words interject: God, let this cup pass! The cello’s tremolo captures the intensity of this fervent, pain-wracked prayer but then smooths out into a legato as Jesus surrenders his will to the Father’s. On “as you will,” a trumpet calls Christ into battle, and he steadies himself to respond.

The next stanza describes Christ’s haggard, blood-soaked appearance. On “bloody be” the instruments play descending scales that indicate Christ’s descent into another bout of distress and incertitude. Again, he prays: God, let this cup pass! (Matthew tells us he prayed it three times.)

Herbert offers a colorful metaphor—two, actually: sin is a press that crushes Jesus into wine, and pain is a hungry animal on the hunt (you can hear pain prowling on “hunt his cruel food”).

After this, though, there’s a change in tone as a heartening fanfare announces the arrival of the New Jerusalem. By splicing this visionary passage into the Gethsemane storyline, Bryant suggests that perhaps Christ looked ahead to the telos of history—the reuniting of heaven and earth, of God and humanity—to bolster his resolve toward the cross.

The last few lines of the song weave the concept of love into that of promise and fulfillment. By crying, sweating, and bleeding in the garden, then dying outside Jerusalem’s gates, Christ established for humankind a new Garden, a new Jerusalem, where “death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Revelation 21:4b). Every time we drink the eucharistic blood of Christ, we taste this promise, and we know Love.

The use of wineglasses as musical instruments in this last segment—a moistened finger circling the rims to produce high pitches—underscores the sacramental theme.

+++

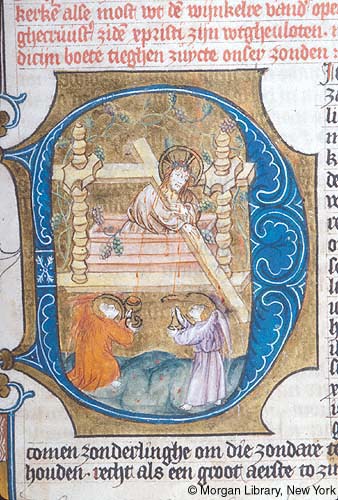

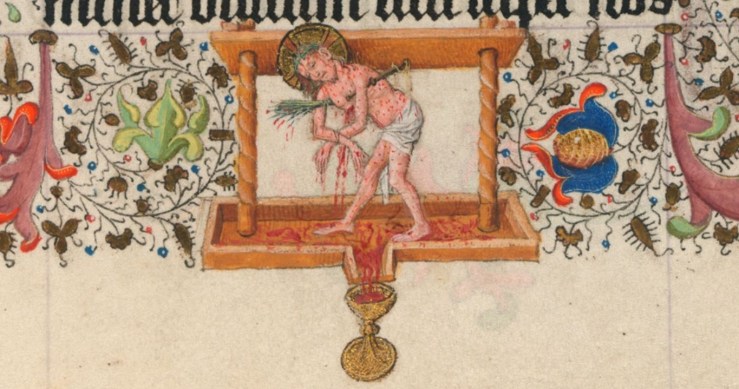

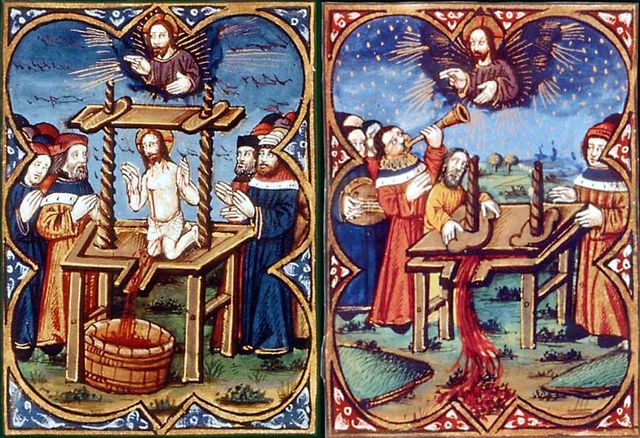

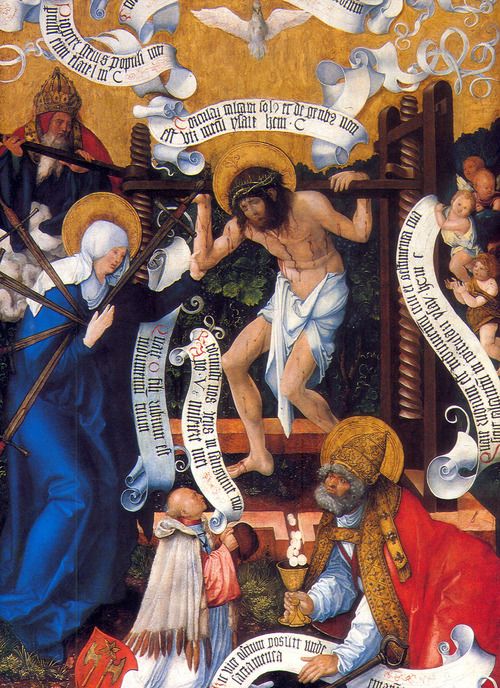

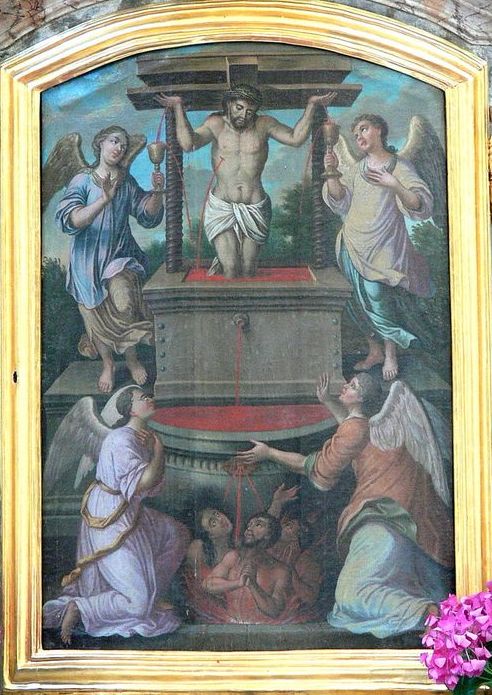

As early as the twelfth century, visual artists have taken up and expounded on the biblically derived symbol of the “mystic winepress” (pressoir mystique), especially in France and Germany, where religious orders were pioneering new winemaking technologies. Most often Jesus is shown as a Man of Sorrows standing on a square wooden flatbed of grapes and being pressed down with them beneath a cross-shaped beam, his “juices” flowing out into a chalice. (The process can be depicted rather graphically, as in the two-picture sequence in a fifteenth-century Bible moralisée, reproduced below.) Sometimes an angel is there collecting the blood, or perhaps sinners awaiting redemption—as in the Salvatorkirche altarpiece in Bogenberg.

In some visualizations, like the oil painting from Albrecht Dürer’s workshop and the Wierix engraving, it is God the Father who lowers the beam that crushes Jesus. This interpretation is inspired by verses like Isaiah 53:10: “It was the will of the LORD to crush him . . .” In others, though, like the stained glass at Saint-Étienne-du-Mont in Paris, it is Jesus who lowers the press down upon himself, emphasizing his agency.

The mystic winepress motif appears in many different media, including manuscript illuminations, frescoes, oil paintings, engravings, wood relief carvings, stained glass—and even terracotta molds for making pastries! (See example above.)

The motif also has some close cousins, such as (1) Christ the Grapevine, an Orthodox image, especially popular in Romania, that shows Jesus squeezing grape juice into a chalice from a vine that’s growing out of his wounded side; (2) the fons vitae (fountain of life), which shows Christ’s blood issuing forth from a fountain, and sometimes the redeemed bathing in it, or lambs drinking from it; and (3) the hostienmühle (host-mill), or mystic mill, which shows the infant Christ being deposited from the machine into a chalice along with the other eucharistic wafers. (The Dürer workshop painting oddly conflates the mystic mill with the mystic winepress, showing Christ treading grapes and little hosts coming out.)

For medieval images of wine pressing, visit http://www.larsdatter.com/winepresses.htm and http://www.wineterroirs.com/2012/12/wine_in_the_middle_ages-.html. For more images of the “mystic winepress” and other blood-/eucharistic-themed variants, see http://imaginemdei.blogspot.com/2017/06/corpus-christ-of-blood-all-price.html.

Dear Victoria Emily Jones,

This is a wonderful post. Thank you so much for your sensitive reading both of Herbert and of the “wine-press” motif in late medieval art. First rate work.

dlj

David Lyle Jeffrey, FRSC

Distinguished Professor of Literature and the Humanities,

Honors Program

Senior Fellow, Baylor Institute for Studies in Religion

Adjunct Professor, Department of Philosophy

Baylor University

Waco, TX 76798-7122

1-254-710-3267

Guest Professor, Peking University

https://www.amazon.com/Books-David-Lyle-Jeffrey/s?ie=UTF8&page=1&rh=n%3A283155%2Cp_27%3ADavid%20Lyle%20Jeffrey

LikeLike

[…] The imagery he introduces – that of the winepress – draws from Scripture, creatively extended (in a tradition dating back to the early church fathers) in a meditation on the shed blood of Christ – gushing out when the spear pierces the side of the dead Jesus – that becomes for us the eucharistic wine. (Some art along these lines is here.) […]

LikeLike

TREADING THE WINEPRESS

By a Carmelite

Who is this Whose Feet are treading

In the winepress of salvation?

Lo the healing wine is spreading

Setting free the captive nation.

As the weight of sine is growing

Thou art still more cruelly pressed;

Precious Blood like wine is flowing

From Thy Hand and Feet and Breast.

O Thou King of wondrous beauty,

Why is Thine apparel red?

Why dost Thou perform this duty,

Letting us go free instead?

“I said ‘They are My chosen nation;

Surely they will not deny Me.’

So I came for their salvation,

And instead they crucify Me.”

“I sought for one to give Me aid,

And to share My grief and pain;

But My friends were all afraid,

Therefore did I seek in vain.”

**********

Dearest Jesus, sad yet lovely,

I have heard Thy anguished cry;

I’ll console Thee, for I love Thee,

Or at least I wish to try.

May Thy cross become my winepress,

Pressing out a precious wine;

Winning souls by loving kindness,

For Thy sake, O Spouse of mine.

When together we have trodden

And the grapes have all been pressed,

All the pain shall be forgotten

In the joy of Heavenly rest.

Cf. Is. 63:1-9

LikeLike

[…] [Related posts: “Hidden in the Cleft (Artful Devotion)”; “The Crushed Christ: An Illustrated Analysis of Herbert’s ‘The Agony’ and Bryant’s ‘Bloo…] […]

LikeLike

[…] relies on a popular motif of his day–the “mystic winepress“–which depicted Jesus being crushed in a winepress, like a grape. Isaiah 53 explains, […]

LikeLike