A masterpiece of French Gothic art, the Latin Psalter of Blanche of Castile was produced in Paris in the first third of the thirteenth century by an anonymous master using tempera, ink, and gold leaf on parchment. The book was most likely commissioned by or for Blanche of Castile (1188–1252), the mother of Louis IX, whom it passed to after her death (which is why it is sometimes referred to jointly as the Psalter of Saint Louis and Blanche of Castile—not to be confused with the even more lavish Paris Psalter of Saint Louis that followed it). Whoever the original owner was, she is depicted praying before an altar on page 122v.

Discussing the transition from Romanesque to Gothic art and the new structures surrounding it, an online Encyclopedia of Art History states,

It is no accident that this new style of Christian art was born in France. The University of Paris was the intellectual centre of Europe throughout the thirteenth century, and from the time of St Louis (1226-70) the French court became increasingly important. Students and scholars from all over the continent flocked to Paris to learn and to discuss scholarly matters. Knights returning from the Crusades introduced Eastern theory and science. [This partially explains the unusual frontispiece depicting three geometers in the Psalter of Blanche of Castile, below.] With the ascendancy of the university, the importance of monasteries as centres of book illustration and illumination declined. Commercial guilds were founded and books were produced for private ownership. Large ceremonial books, lavishly illuminated and ornamented with jewellery, became less common and we must follow the stylistic developments principally in Psalters, which the highborn laity made their own.

An alternate name for the manuscript is the Sainte-Chapelle Psalter, due to the fact that it was preserved in the Sainte-Chapelle treasury from 1335 to the end of the eighteenth century, when it was moved to the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, now part of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Louis IX built the Sainte-Chapelle (“Holy Chapel”) inside the royal palace complex between 1238 and 1248 to serve as a private devotional space and to house the thirty-plus relics of Christ he had bought, including what he believed to be the crown of thorns and a fragment of the cross.

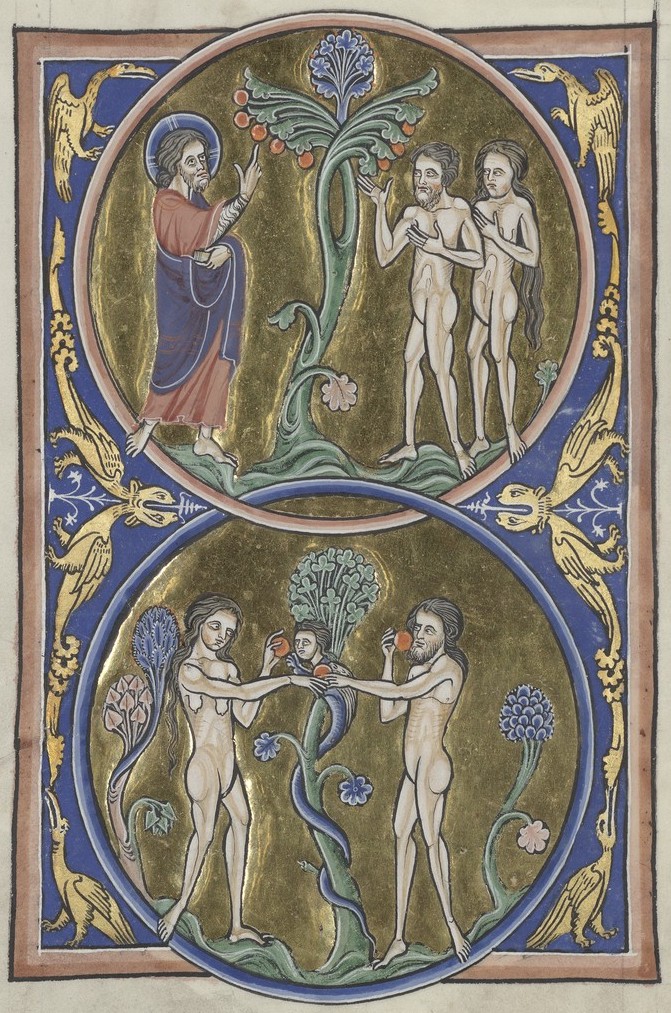

Among the 192 pages of the Psalter of Blanche of Castile are twenty-seven full-page miniatures, twenty-two of which are divided into interlocking medallions containing distinct narrative episodes from the Old and New Testaments (mostly). All of them are reproduced below, sourced from https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7100723j (Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal MS 1186 réserve). Folio numbers and subjects are provided as captions.

This is one of thousands of Christian illuminated manuscripts that have been digitized by libraries and museums around the world, enabling people like you and me to be nourished by their beauty. People often ask me how I incorporate visual art into my devotional practice, and one way is by simply paging (digitally) through painting cycles from old books, letting the medieval imagination be my guide through God’s story of redemption. My eyes do the reading, my soul rests. There’s no rigid program I follow, and no particular goal, but I find I am often led to respond in prayer. Try it!

In the lower scene on the following page, even the sheep eagerly incline their heads to receive the announcement that a Savior has been born!

I’m not sure who the naked man on the column is supposed to represent in the illumination below; my best guess is that he is an idol being toppled from his pedestal, along with a demon, since God has come in Christ to assert his supremacy over them. But he doesn’t much look like a god, and he doesn’t look like a demon either, so I’m not sure. He looks too old to be one of the children murdered by Herod. Any other guesses?

[Who are Ecclesia and Synagoga?]

Above, it’s interesting to see these two Resurrection appearances on the same page, because in his encounter with Mary Magdalene, Jesus says, “Don’t touch me” (Latin Noli me tangere)—or more accurately, “Don’t cling to me”—whereas to Thomas he says, “Touch me!” (“Put out your hand, and place it in my side”). That’s because the faith formation of these two disciples required personalized approaches: Mary needed to loosen her grip on Jesus’s physical presence, but Thomas needed to strengthen his. Mary’s desire to commune with Christ was so strong that he needed to prepare her for his inevitable ascension to the Father, reminding her that spiritual communion would still be possible; Jesus’s instruction to refrain from embracing him was his way of helping to tutor her in this new mode of interacting. Thomas, on the other hand, was incredulous that Christ had risen bodily from the dead, and he needed the physical presence of his teacher and the gentle instruction to look and to touch so that he could confirm what had only been rumored and thenceforth boldly profess this gospel truth.

The Virgin Mary is usually shown in the center of Pentecost paintings, but in this one, that spot is occupied by a tonsured man holding a book, one of thirteen in the group. Medieval monks and clerics in the West typically wore this kind of haircut, which was believed to have originated with St. Peter, but I can’t say with confidence who this central figure is supposed to represent.

One of the titles Catholics give to Mary is Regina Coeli, “Queen of Heaven,” and she has been represented in art as such many times throughout history. I myself am not too receptive to this iconography, but when I consider her as a representative of the church (Catholics call her Mater Ecclesiae), the bride of Christ, it helps.

I can’t tell whether the bottom scene in the previous image refers to a specific biblical episode. I’m assuming the crowned figure is David (Louis IX had not yet become king), and the men he’s interacting with are wearing “Jewish hats.”

I don’t know what’s going on in the top three half-medallions above. In the right one there appears to be a murder, and said murderer is in the bottom scene being tormented by demons, his soul carried off to hell. If you recognize the other two episodes, please let me know!

Though scales are occasionally used in the Bible as a symbol of God’s righteous judgment, I find the “weighing of souls” (psychostasis) motif in Christian iconography to be theologically problematic (from a Reformed perspective), because one’s admission to heaven is based not on a hefty amassing of one’s own good works but on the good work of Christ on the cross. We are all found wanting when our personal merits are weighed against God’s perfect standard of righteousness! But those to whom Christ’s merit has been imputed (those who confess him as Lord and enter into his death and resurrection) will find themselves in perfect balance with God’s law on the last day, because God’s mercy has calibrated their pan.

While I don’t expect images to carry the same precision as verbal or written theology, and I certainly don’t expect pre-Reformation images like this one to propound Reformation teachings, I do try to be theologically discerning when it comes to viewing images. Images are not theologically neutral! They communicate. That doesn’t mean we should stick to viewing images only from our own tradition (by no means! what a richness we would forgo) but, rather, couple the practice with the reading of scripture and even discussion in community. What will the Last Judgment look like, according to scripture? How does the artist imagine the event? What symbols does he use? Where do scales appear in the Bible? How do God’s mercy and justice interrelate? Does the artist convey both attributes, or is one given prominence over the other? What is the eternal consequence of our deeds, good and bad?

I would say the image above captures the ongoing spiritual battle between good and evil, how Satan tries to drag us down, and warns that we will all be called to account someday. I would push back against the suggestion that our eternal destination is dependent on our good works (signified by a stack of pebbles) outweighing our bad. But the scale provokes associations of measures, which reminds us that God has a standard of holiness, a known weight, and that living by that standard has worth.

To preview and/or purchase a facsimile edition of the Psalter of Blanche of Castile, click here.

Victoria: You asked about the figures on pedestals in the Flight to Egypt scene (fol. 19v). I’m pretty sure that its source is the apocryphal Infancy Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the legend of the fall of the 365 idols in a temple called the “Capitolium of Egypt” in the city of Sotinen.

LikeLike

Ah, yes, that’s right! Since publishing this post I came across that story but haven’t added an update. Thanks for the source.

LikeLike