One of the joys of blogging at Art & Theology is being introduced to new artists by my readers. I was pleased to receive in the mail recently, as a gift from one such reader, a color booklet and a 2018 documentary on the art of Dom Gregory de Wit (1892–1978), a Dutch artist and Benedictine monk who between 1938 and 1955 lived in the United States painting murals for Catholic churches and monasteries. This was the first time I’ve encountered the artist, and I enjoyed getting to know him better through these materials.

All photos in this post are provided courtesy of Edward Begnaud or Stella Maris Films.

Gregory was born Jan Aloysius de Wit on June 9, 1892, in Hilversum, Netherlands. He entered the monastic life in 1913 at age twenty-one, joining Mont César Abbey in Leuven, Belgium, and there taking the name Gregory. (His interest in liturgy and ecumenism is what drew him to that particular abbey.) de Wit was passionate about art making since a young age, and his order encouraged him to further develop his talent as a painter. He therefore studied at the Brussels Academy of Art, the Munich Academy, and throughout Italy. In 1923 he exhibited at The Hague and ended up selling forty-five paintings in one month! He then went on to fulfill three sacred art commissions—one in Bavaria, two in Belgium—while continuing to live as a monk.

In 1938, Abbot Ignatius Esser of Saint Meinrad Archabbey in southern Indiana met de Wit in Europe and invited him to design and execute paintings for the abbey’s church and chapter room—which he gladly accepted.

Here he started to develop his own style, which would come to be marked by brilliant (sometimes garish) colors, bold outlines, distortion or disfiguration (e.g., disproportionate hands), and “overlapping” perspective.

In Christus, Jesus is borne upward by a red-winged chariot. In his right hand he holds a victory wreath, and in his left, an open book that declares, EGO SUM VITA (“I am the Life”). The three small Greek letters in the rays of his halo, a traditional device in Orthodox iconography, mean “I am the Living One,” a New Testament echo of God’s “I am who I am” in Exodus 3:14.

+++

Shortly after de Wit arrived in the US, World War II broke out, and even after he completed his work at Saint Meinrad, he couldn’t return to Belgium. Luckily, another stateside commission came his way, from the newly built Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The parish priest, Father Dominic Blasco, hired him to paint a series of murals, which resulted in de Wit’s most polarizing work: his Christ Pantocrator in the apse behind the altar. Many of the parishioners hated it (and I have to say, I’m not partial to it). A humorous anecdote in the documentary recalls Maria von Trapp, who had once visited the church, expressing her horror at the image to de Wit, not knowing he was its artist!

Not only did de Wit’s art garner dislike, but so did his temperamental personality and sometimes irreverent behavior. For example, while at Sacred Heart, he smoked while he painted, dropping cigarette butts onto the floor during services. Although he did have his supporters, he was eventually fired from Sacred Heart. The last painting he did for the church was of the Samaritan woman at the well—descried as “pornographic” by the sisters of the school because of the suggestive way her dress clings to her forwardly posed thigh.

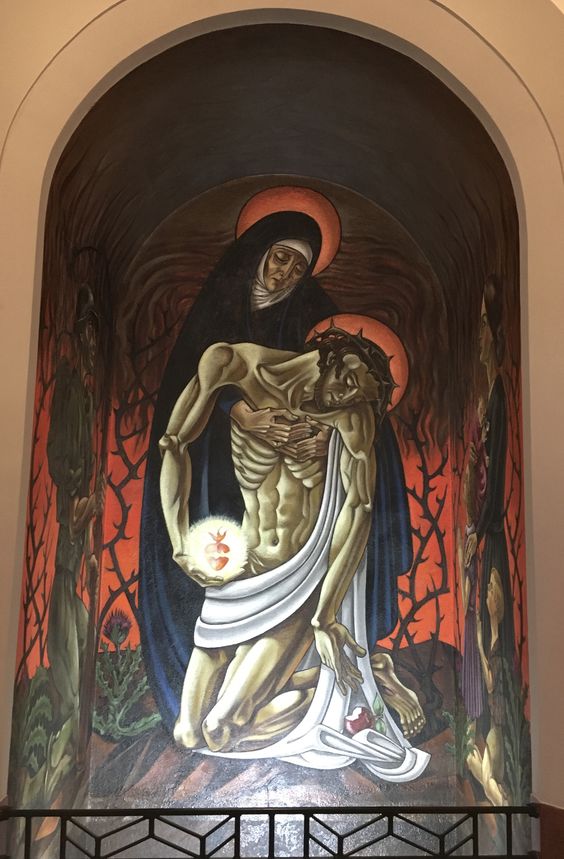

The painting at Sacred Heart that I’m most intrigued by is the Pietà in the narthex, which shows Mary holding her dead son. Genesis 3 is invoked by the thorns that not only crown Christ’s brow but that rise up all around him, symbolic of the curse. What’s more, a half-bitten apple rolls from his limp hand; he, like his forefather, Adam, has tasted death. And this he did willingly out of love, signified by the fiery, thorn-enwrapped heart of his that he holds in his right hand, whose glow illuminates the darkness.

Because de Wit painted this image during the war, it is contextualized with a soldier on one side and the soldier’s wife and three children on the other, praying for his safe return. Why do they belong in this scene? Some wartime artists drew parallels between Christ and the soldiers’ sacrificial laying down of their lives (cf. John 15:13). I’m uneasy with this comparison for several reasons, not least of which is my Christian pacifism. But de Wit’s painting seems, rather, to use the soldier and his family as a representation of war and to suggest that Jesus, the Suffering Servant, is with us in our present suffering. He entered our world, after all, and died to redeem us from its evils—sin and death and all their extensions. The presence of Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, must have been a comfort to the mothers at Sacred Heart whose sons were overseas fighting.

Moreover, even though its hieratic style may be off-putting to some, I also really like the crucifix de Wit created for Sacred Heart (but which is now at St. Paul the Apostle Catholic Church, also in Baton Rouge). The corpus is painted on solid mahogany, with real nails driven through the hands.

+++

After leaving his post at Sacred Heart, de Wit went on to carry out what would become his magnum opus: the murals in the church and refectory (dining hall) of Saint Joseph Abbey in St. Benedict, Louisiana. Commissioned in 1946, de Wit worked on this extensive decorative program for nine years, completing it in 1955. It is the subject of the forty-six-page, full-color monograph Living in Salvation: The Murals of Gregory de Wit at Saint Joseph Abbey by Adam Begnaud, OSB, a monk at the abbey at the time of publication in 2005. (Since leaving the monastic life, Adam has returned to his lay name, Edward Begnaud, and is interviewed as such in the recent documentary.)

Begnaud discusses in detail the many paintings at Saint Joseph and how they contribute to the overall scheme. He starts in the refectory, admiring how in the fifty-six Creation panels on the ceiling, “the four elements of ancient cosmology (earth, air, water and fire) and the creatures that dwell in them all participate in the drama of salvation” (7). Birds, fish, buffalo, deer, and other living things cavort in nature, along with the twelve signs of the zodiac. Begnaud points out that Psalm 145:15–16 is recited in the traditional Benedictine meal prayer and likely inspired de Wit: “The eyes of all look to you, / and you give them their food in due season. / You open your hand; / you satisfy the desire of every living thing.” Psalms 148 and 150:6 also come to mind.

Also in the refectory, one of nine painted vignettes, is the “protoevangelium,” the first glimmer of the gospel we receive in scripture. de Wit’s visual interpretation juxtaposes Adam and Eve holding Cain with the Virgin Mary (the “New Eve”) adoring the newborn Christ (the “New Adam”). The ancestral couple looks haggard, sin-weary and groaning for redemption beside a barren tree. That redemption comes in the foreground, signified by blooming flowers and the haloed Christ child, who cradles something in his hands that’s difficult to identify but that could be flowers, his heart, or a pomegranate, the fruit of life.

This compact image displays both the demise and regeneration of creation, Begnaud writes, and invites us into that story: “Working from background to foreground rather than left to right, Gregory demonstrates a depth to time which converges on the viewer. This approach results in the viewer being forced into direct involvement with the narrative” (13).

The text that frames the figures is taken from two sixth-century hymns by Venantius Fortunatus, from right to left: “Pange, lingua” (Sing, My Tongue) and “O Gloriosa Domina” (O Heaven’s Glorious Mistress).

Pomi noxialis morsu in mortem corruit.

The harmful fruit having been bitten, he [Adam] fell into death. (trans. Giuliano Lupinetti)

Quod Heva tristis abstulit,

Tu reddis almo germine.What man had lost in hapless Eve,

Thy [Mary’s] sacred womb to man restores. (trans. R. F. Littledale)

Moving to the Romanesque abbey church, we see Christ vividly proclaimed as Alpha and Omega, from whom we all came and to whom we all return. In the eastern apse Christ rises like the sun, in all his resurrection glory, enlightening the world. Opposite that, at the west end, is a painting of the Last Judgment, unique in its omission of the condemned. As Begnaud notes, this mural presents de Wit’s theological views on the nature of the final judgment by him who came not to condemn but to save (John 3:17), to give life and life abundantly (John 10:10). Christ is seated on a rainbow, a sign of promise, with an open book that reads, “I will be thy great reward,” and the banderole at his feet says, “All flesh to thee shall come” (Psalm 65:2).

This psalmic declaration finds visual expression in the range of people flocking to Christ—the sick and disabled, orphans and widows, laborers and musicians, businessmen and soldiers, bishops and nuns. One might expect Saint Benedict, whose Rule the abbey follows, to occupy a position of privilege in this line-up, but in fact he appears behind the crowd, gesturing toward Christ. In front of him, in the most prominent position at Christ’s right hand, is a black man with a shovel and ax. Painted in the American South in the 1950s, this was a brazen civil rights declaration—African Americans, like everyone else, are from God and in God and deserve dignity and respect.

Also making an appearance in this sacred throng, in his black religious habit at the right, is de Wit himself, holding his instruments of praise: a palette and brushes.

+++

During his career, de Wit fulfilled art commissions elsewhere in Louisiana and in Texas and California. He returned to Europe in 1955, eventually settling in Switzerland and becoming a hermit, continuing to paint and also to write. He died in 1978.

+++

In Living in Salvation, Begnaud gives a fair assessment of Gregory de Wit’s art. He is appreciative of it but doesn’t overblow the artist’s genius or influence. Aware of de Wit’s flaws, he writes, “Gregory does demonstrate a lack of proficiency in certain areas, which prevents him from being a truly great artist. His weaknesses are most evident when Gregory moves away from a strong graphic presentation and degenerates into a childish rendering” (5). Some of his works are “amateur,” “lack[ing] sophistication,” “sophomoric” (9). But his strength, according to Begnaud, is his ability to organize and execute a comprehensive design program, making the whole of a space a single “canvas,” and his bridging of Western art and Eastern iconography. de Wit also succeeds in bringing to life a vibrant Christocentric theology.

I agree with this assessment. The quality of de Wit’s work is uneven (and granted, I haven’t had the benefit of seeing it in person)—but he has produced some compelling paintings, most of which I’ve featured here. And as Begnaud says, seeing the paintings in isolation doesn’t enable their full impact, which comes only when you see them in light of their larger program. I encourage you to explore more of de Wit’s work and see what you think.

The recently released hour-long documentary Hand of the Master: The Art and Life of Dom Gregory de Wit, directed by David Michael Warren and narrated by Kitty Cleveland, is available for streaming on Amazon Prime and can be purchased on DVD from Stella Maris Films. It features on-site interviews with friends, monks, historians, and archivists; extensive photography of the artworks; and some historical photos and audio of de Wit himself.

concerne : Grégory de Wit

Pour moi qui n’était qu’une enfant dans les années 1970, je l’appelai : le Père Grégoire, mon papa a fait sa connaissance à Longeborgne et de cette rencontre ils sont restés en contact, liés, dans mes souvenirs mon papa allait régulièrement à Oberems en Valais (Suisse) prendre son linge pour le laver. Malheureusement mon papa n’est plus lâ pour me raconter leur relation, les anecdotes. Je fais des recherches sur le Père Grégoire car j’ai plusieurs peintures, dessins que mon papa avait reçu, certains sont des portraits de papa à ses 17 ans, grand-maman, paysage et religieux.

LikeLike

Bonjour,

Formidable votre témoignage! Je m’intéresse aussi au Père Gregoire car j’ai une peinture de lui, une vierge magnifique datée de 1939. Peut-être pourrions nous échanger les photos de nos oeuvres? Je serai très curieuse de voir les vôtres…Je vous laisse mon adresse mail: mariewatteau@orange.fr

A bientôt!

Marie Watteau ( Bordeaux, France)

LikeLike

Don Gregory also had a sense of humor. The seating was fixed at the refectory at St. Joseph Abbey. There were two monks who were supposedly jealous of the attention Dom Gregory was receiving. As a result, he painted two donkeys on the ceiling that covered them today. Also, in the same refectory, the table depicting the Last Supper is set with salt shakers.

LikeLike

[…] The Art of Dom Gregory de Wit […]

LikeLike

[…] Crucifix (detail) by Gregory de Wit, St. Paul the Apostle Catholic Church, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, courtesy of Victoria Emily Jones / Art & Theology […]

LikeLike