VISUAL MEDITATION: On The Alpha & The Omega by Betye Saar: A few weeks ago my commentary on a Betye Saar installation was published on ArtWay.eu. The idiomatic Hebrew in the title is a reference not to Christ but to the beginning and the end of life, a theme Saar explored by arranging around a blue-painted room such found objects as an antique cradle, dried hydrangeas, a boat shell, a mammy figurine, a washboard, empty apothecary bottles, books, clocks, a moon-phase diagram, etc.

With an educational background in design, Saar began her career as a printmaker and working in theater on costumes and sets. She then ventured into collage, which led to assemblage (for which she is most celebrated), sculpture, and installations. With installations, she likes how “the whole body has the experience”—how you are quite literally inside the work. Saar is one of today’s leading American contemporary artists, with two exhibitions currently running in the United States: one at MoMA, and the other at LACMA. I first encountered her in a college art history course, through her most famous work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima. Race, memory, and spirituality are recurring themes in her oeuvre.

+++

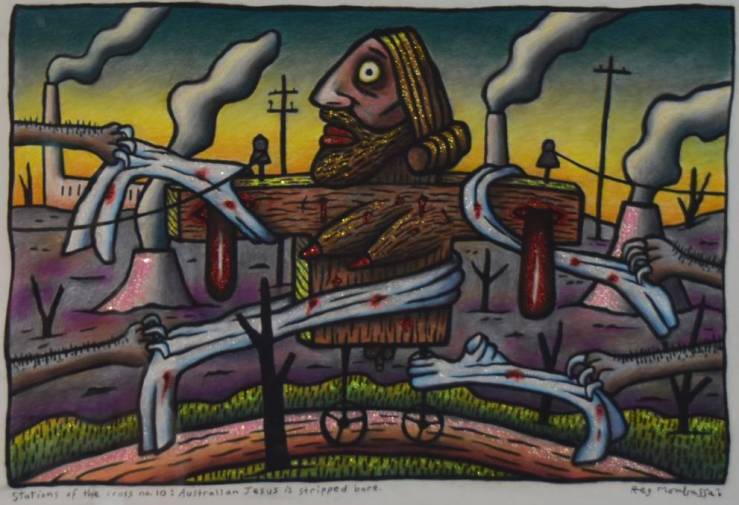

ESSAY: “‘A pretty decent sort of bloke’: Towards the quest for an Australian Jesus” by Jason A. Goroncy: “What happens to religious images and symbols when they get employed outside of their traditional contexts and charged with unapproved and heterodox interpretations?” asks Goroncy. “From many Aboriginal elders, such as Tjangika Napaltjani, Bob Williams and Djiniyini Gondarra, to painters, such as Arthur Boyd, Pro Hart and John Forrester-Clack, from historians, such as Manning Clark, and poets, such as Maureen Watson, Francis Webb and Henry Lawson, to celebrated novelists, such as Joseph Furphy, Patrick White and Tim Winton, the figure of Jesus has occupied an endearing and idiosyncratic place in the Australian imagination. It is evidence enough that ‘Australians have been anticlerical and antichurch, but rarely anti-Jesus’. But which Jesus? In what follows, I seek to listen to what some Australians make of Jesus, and to consider some theological implications of their contributions for the enduring quest for an Australian Jesus.” [HT: Art/s and Theology Australia]

Goroncy quotes Wilson Yates, who says that Jesus has become “a part of the culture and life far beyond the final control of the church, . . . imaged in diverse ways by non-Christian as well as Christian artists, often contrary to the church’s dominant interpretation. . . . This should not be viewed as threatening,” however, but rather as “a means by which, paradoxically, the traditional symbols are kept vital – are kept alive in the midst of human life.”

+++

AUDIO INTERVIEW: Justin Paton on New Zealand artist Colin McCahon: In celebration of the centenary of Colin McCahon’s birth, art critic and curator Justin Paton has published McCahon Country, which examines nearly two hundred of the artist’s paintings and drawings. In this Saturday Morning (RNZ) interview, Paton says that McCahon is one of the great modern religious artists; an unabashed Christian, he grappled with how to make religious art in a post-religious age, often interweaving biblical themes and texts with New Zealand landscapes. His paintings, Paton says, are “an unequivocal statement of faith,” painted at times with “sophisticated unsophistication.” In 1948 one critic described them dismissively as “like graffiti in some celestial lavatory”—a comparison Paton affirms but sees as commendatory.

I was familiar with McCahon’s early works—Annunciations, Crucifixions—but not so much the later ones featured here. For example, The days and the nights, about which Paton says,

You could take a first look at this thing and you could think it’s not so exciting, in a way. It’s . . . smeary blacks and then there’s this . . . kind of clay color—muddy, you might say. . . . The form is this kind of ocher cross with black surrounding it. But give it some time, and you realize that the space above describes a horizon line. You can see the riffle of clouds along that horizon. If you know Muriwai on the West Coast, you can recognize it as a West Coast landscape, which is of course the spirit landscape up which souls travel in Maori mythology. And then you realize that this cross is also a kind of estuary, that it is descending through to areas or gates. So it is at once the Christian cross, it’s the Buddhist idea of light as grace which descends towards us . . .

About Lazarus:

McCahon said the Lazarus story was one of the great stories about seeing: all those people who were witnesses to this event saw as never before. What’s wonderful in the work is, as you read your way from left to right—and it really is this kind of epic telling of the story—when you’re about two-thirds of the way across, he almost makes you into Lazarus. He puts you into the position of this person who is emerging from the tomb, because there’s this sliver of light that opens up and bursts then fills the right-hand third of the painting. It’s like coming out of a dark space and suddenly being blinded by sunlight.

It’s a great example of what a great reader he was. He got into these texts with the avidity of a fan. You really felt he was there with these people in this ancient story and then tries to put us inside it as we stand and walk in front of this giant canvas. It has a terrific oscillation between something worldly and vernacular and then something exalted and sacred at the other end.

For more on McCahon, see “Victory over death: The gospel according to Colin McCahon” by Rex Butler (2012), The Spirit of Colin McCahon by Zoe Alderton (2015), and Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith (2003).

+++

CHANT: “I Am Here in the Heart of God” by Erin McGaughan, adapt. & arr. Chandra Rule: At the Singing Beloved Community workshop held in September in Cincinnati, song leader Chanda Rule led participants in a chant that she adapted from Erin McGaughan. To McGaughan’s original, Rule added three new verses with a modulation between each, and she presented the whole of it in a call-and-response format. [HT: Global Christian Worship]

I am here in the heart of God

God is here in the heart of me

Like the wave in the water and the water in the wave

I am here in the heart of GodI am here in the breath of God

God is here in the breath of me

Like the wind in the springtime and the springtime in the wind

I am here in the breath of GodI am here in the soul of God

God is here in the soul of me

Like the flame in the fire and the fire in the flame

I am here in the soul of GodI am here in the mind of God

God is here in the mind of me

Like the earth in my body and my body in the earth

Like the flame in the fire and the fire in the flame

Like the wind in the springtime and the springtime in the wind

Like the wave in the water and the water in the wave

I am here in the heart of God

+++

SONG: “I Hunger and I Thirst,” words by John S. B. Monsell (1866), with new music by Wally Brath: I was listening to the video recording of the Grace College Worship Arts jazz vespers service that took place November 8 at Warsaw First United Methodist Church in Indiana, when I heard this striking hymn. Written by a nineteenth-century Anglican clergyman, it was set to music by Wally Brath, an assistant professor of worship arts at Grace College, who’s playing the piano in the video. The performance features Grammy Award–winning bassist John Patitucci, and vocalist Ethan Leininger. Click here to listen to the whole service and to see the full list of musicians. [HT: Global Christian Worship]

I hunger and I thirst:

Jesu, my manna be;

ye living waters, burst

out of the rock for me.Thou bruised and broken Bread,

my life-long wants supply;

as living souls are fed,

O feed me, or I die.Thou true life-giving Vine,

let me thy sweetness prove;

renew my life with thine,

refresh my soul with love.Rough paths my feet have trod

since first their course began:

feed me, thou Bread of God;

help me, thou Son of Man.For still the desert lies

my thirsting soul before:

O living waters, rise

within me evermore.

I love the chant you have featured.

Thanks

LikeLike

What a wonderful post! I love these musical selections. I’m going to do the “I Am Here in the Heart of God” as my next children’s sermon at my parish, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Del Mar, CA. Thank you so much for your beautiful and thoughtful posts.

In Christ, The Rev. Martha Anderson

LikeLike

I just love this post! The art is so interesting and the chant was so amazing! I want to listen to it more!

LikeLike

[…] reverberant landscape painting Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is by Colin McCahon [previously] shows a sun setting behind a range of dark New Zealand hills, with a gray body suggesting water in […]

LikeLike

[…] means “holy.”) In this original composition for voice, piano, and string quartet, Wally Brath [previously] has integrated this Hebrew exclamation from the book of the prophets with an English excerpt from […]

LikeLike

[…] Press Association awarded silver prize for “Best Theological Article” to Jason Goroncy [previously] for this piece. (How cool that it won in the theology category!) Like all art, street art can […]

LikeLike