(All photos in this article are my own, taken either by me or my husband.)

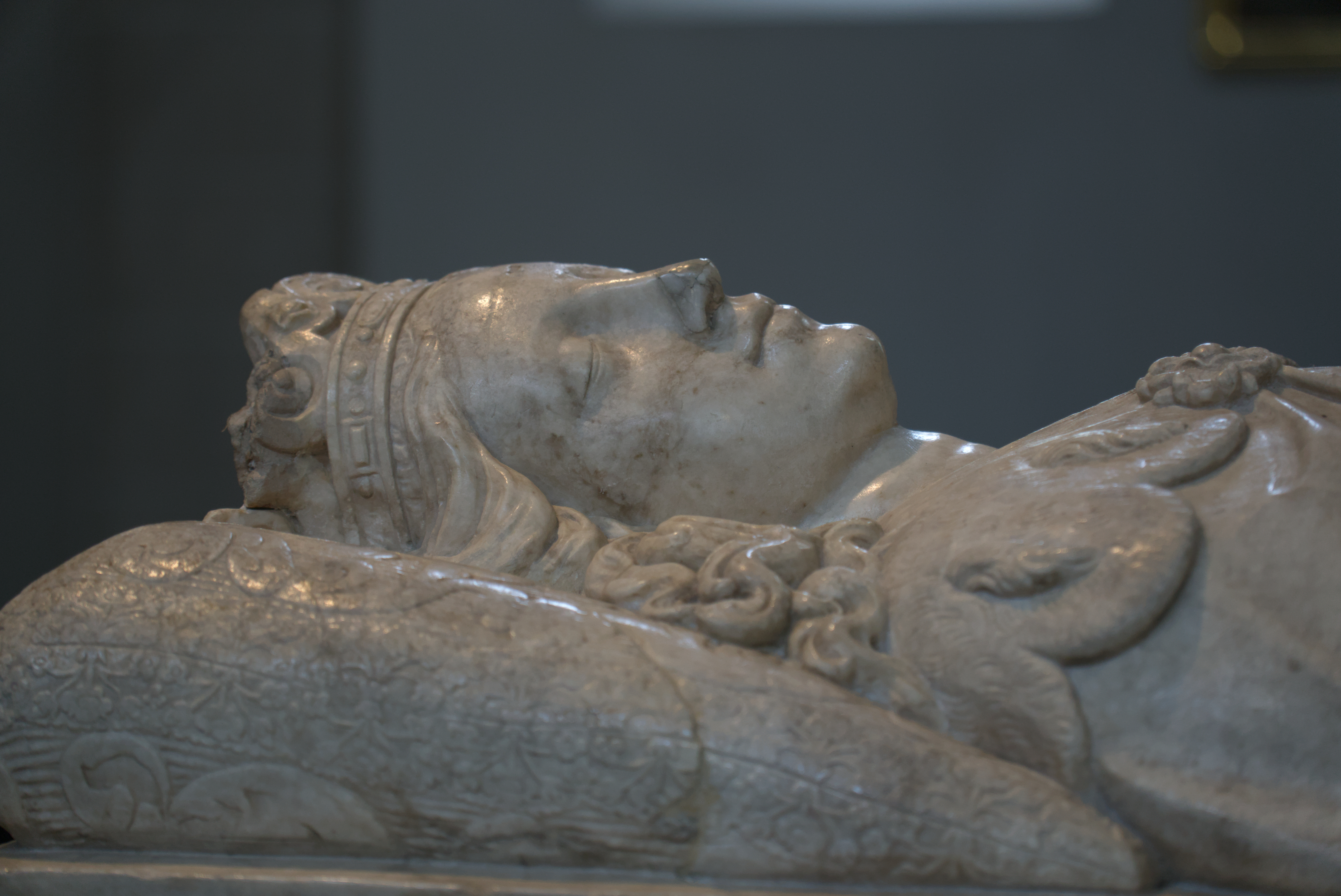

I knew very little about the virgin martyr St. Ursula before visiting the basilica dedicated to her in Cologne, Germany, last month. She’s the patron saint of the city, where, according to hagiography, she was murdered sometime in the fourth century.

There’s no historical veracity to her story, which is why her name was removed from the Catholic calendar of saints when it was revised in 1969. But her feast day is still observed by many on October 21.

As legend has it, Ursula was a Romano-British princess and a Christian. She was engaged to be married to a pagan prince. To delay the wedding, she successfully requested that she first be allowed to take a three-year pilgrimage to Rome, and that she be accompanied by eleven thousand virgins (a ridiculous number that was likely embellished from what was originally eleven). On their voyage, she converted all eleven thousand to the faith.

On their way back to Britain from Rome, they were traveling through Cologne when it was besieged by the Huns, a group of nomadic warriors from Central Asia. Ursula and her companions refused the soldiers’ sexual advances and were slaughtered as a result. One version of the legend says the women’s souls then formed a celestial army that drove out the Huns, saving Cologne.

The earliest possible reference to Ursula and company—though they are unnamed and unnumbered—is a stone plaque dated to 400. Now incorporated into the choir wall of the present Basilica of St. Ursula, it mentions a basilica restored on this site by the Roman senator Clematius to commemorate the “martyred virgins coming from the east, in fulfillment of a vow, . . . holy virgins [who] spilled their blood in the name of Christ.” This inscription not only provides the seed of what would become the Ursula legend; it’s also the earliest evidence of Christianity in Cologne, attesting to the presence of a church there in the fourth century.

It wasn’t until the tenth century that the name Ursula emerged, identified as the leader of the group of virgins, and that their number, which had previously ranged from two to thousands, became fixed at eleven thousand. The women were never officially canonized, but their veneration as saints grew immensely in the twelfth century after a large, late antique Roman cemetery was discovered in 1106 near the aforementioned Church of the Holy Virgins in Cologne during an excavation project to expand the city’s fortifications. The skeletal remains in the hundreds of graves were purported to be those of the martyred women (notwithstanding the presence of many men’s and children’s bones among them).

The discovery of these putative relics called for the rebuilding of the predecessor church to house them. Construction began in the second quarter of the twelfth century, and it’s that structure, with later renovations, refurbishments, additions, and (post–World War II) restorations and repairs, that stands today. The church was elevated to the status of minor basilica in 1920.

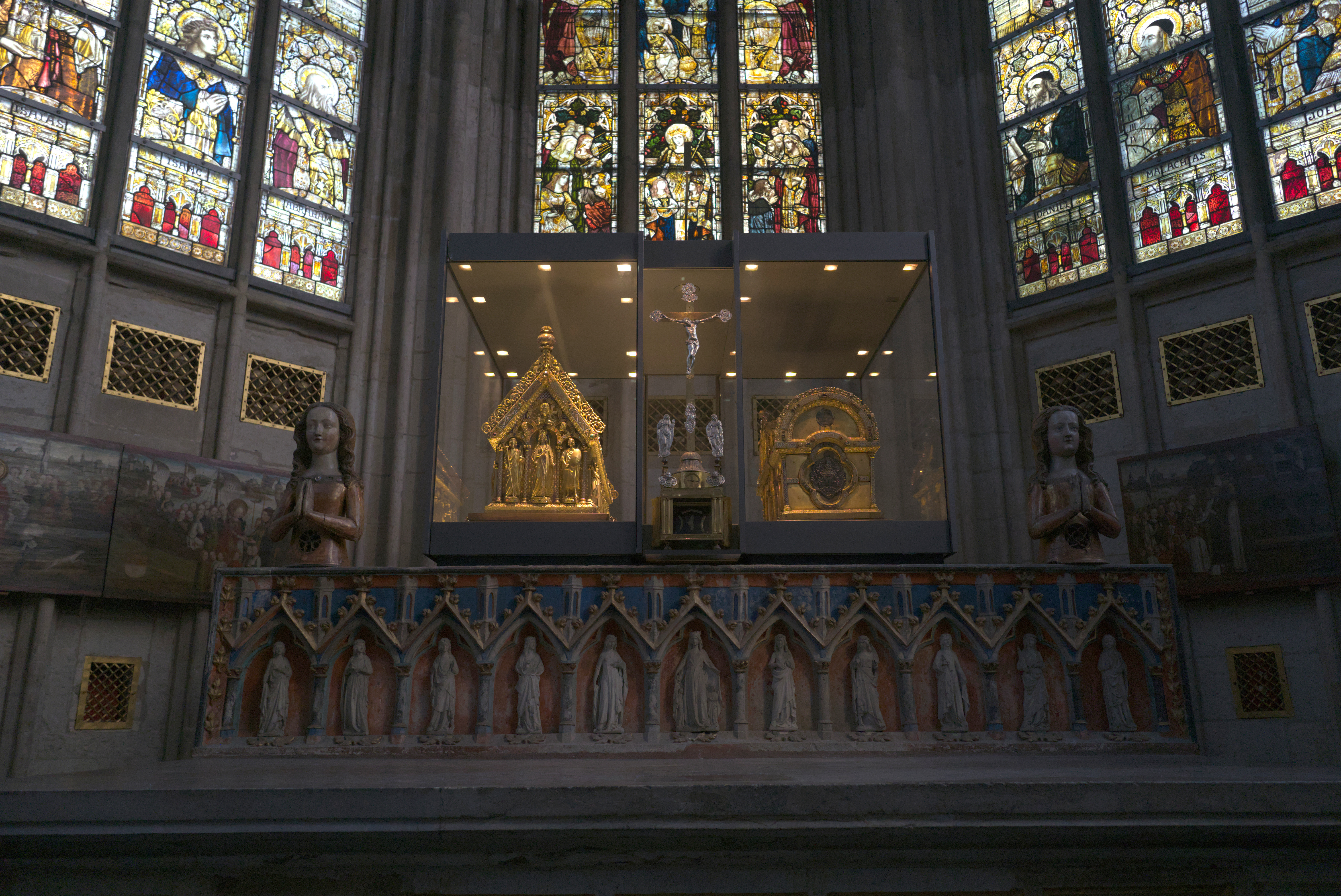

The reason the Basilica of St. Ursula was on my list of stops was I wanted to see its so-called Golden Chamber.

The Golden Chamber

The largest ossuary north of the Alps, the Goldene Kammer (Golden Chamber) is decorated with the bones of, allegedly, St. Ursula and her eleven thousand travel mates, which are artfully arranged across the walls in geometric patterns, rosettes, and even words! Unlike most other relic displays I had seen before, where the relics are kept in some kind of encasement and usually only partially visible, this one puts many of the bones right out in the open, making the whole room a walk-in reliquary.

A Baroque marvel, the Golden Chamber was established on the south side of the church in 1643 through a donation by the imperial court councilor of the Holy Roman Empire Johann von Crane and his wife, Verena Hegemihler. It replaced a smaller medieval camera aurea (treasury and relic chamber), where the bones had previously been displayed. Crane and Hegemihler oversaw the design and construction of the space, with its ribbed, star-studded, sky-blue vault, and the arrangement of the bones into their present form.

Above the altar, tibias, fibulas, femurs, humeri, and other bones spell out “Sancta Ursula Ora Pro Nobis” (Saint Ursula, pray for us). Also rendered in bones are the name Etherius—Ursula’s fiancé, who converted to Christianity at her insistence and met her in Cologne to die with her—and a mention of the holy virgins.

Other sections of the wall use vertebrae, pelvic bones, ribs, shoulder blades, and so on to create ornamental designs like hearts, spirals, webs, flowers, and crosses.

Similar visual displays of bones in charnel houses, writes art historian Jackie Mann, had become increasingly common in Europe by the late fourteenth century.

The shelving cabinets below the bone decor belong to the second phase of furnishings around 1700. They contain niches that house 112 reliquary busts (most of them produced between 1260 and 1400 and made of polychromed wood), as well as gilded acanthus tendrils that encompass some 600 skulls. Out of reverence, many of the skulls are at least partially wrapped in red velvet with gold and silver embroidery made by the nuns of the nearby Ursuline convent.

Occasionally, where the wrapping has slipped, you’ll see an eye hole staring back at you.

To account for the presence of men’s bones in the ancient Roman churchyard, the legend of St. Ursula was adapted in the twelfth century to include male martyrs—namely, Etherius and his retinue. That’s why the Golden Chamber contains several male busts alongside the female.

To the average person, the Golden Chamber is a weird, macabre spectacle. But for Catholics, displaying human bones is not meant to be creepy or horror-inducing. Rather, by bringing remnants of the dead into spaces of the living, we are reminded of: (1) our own mortality, (2) the community of saints that transcends time, and (3) the promise of universal, bodily resurrection (dem bones gonna rise again!).

Memento mori (“remember you will die”) was a common trope in seventeenth-century art and devotion, meant to increase one’s awareness of the fleetingness of life and to encourage one to live in light of heaven. Mann calls the Golden Chamber an “immersive memento mori.” Again, the traditional Christian summons to remember our mortality is not meant to frighten. It’s meant to inspire us to live whole and holy lives.

While death is an ending in one sense, it’s also an entry into life immortal. The Golden Chamber gathers together the fragments of local saints that had been scattered in ancient burial ruins, preserving them for the saints of later generations as a witness that our bodies will never be finally lost; they will be raised and renewed by God on the last day and reunited with our souls. Christians treat the remains of the deceased with honor in recognition that our bodies—including the framework of bones that support our soft tissues, protect our organs, enable our movement, store minerals for our use, and produce our blood cells—are not just temporary shells encasing who we really are, but rather are a part of who we are. Hence why we proclaim, in the Apostles’ Creed, that “we believe . . . in the resurrection of the body.”

Memorial for the Martyrs of Today

While the Golden Chamber is the primary draw for visitors to the Basilica of St. Ursula, there are other sights in the church worth spending time with, ones I was not expecting. One of them is the Gedenkstätte für die Märtyrer der Gegenwart (Memorial for the Martyrs of Today), a chapel in the south transept that commemorates the Christians in Cologne, both religious and lay, who were killed for resisting the Nazi regime—or, in the case of Sr. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) and Elvira Sanders-Platz, for being ethnically Jewish.

Made by the architectural and design firm Kister Scheithauer Gross, the chapel consists of a double-shelled, slightly transparent canvas construction printed on the inside with the names and dates of the martyrs, as well as quotes they gave before their deaths. Sunlight enters from the window to the right of the chapel, causing the space to glow. There’s a small bench on each of the three sides, for people to sit and pray or reflect.

In the center is a life-size wood crucifix. The gaunt Christ figure is pierced all over and bears a deep wound in his side where the centurion’s spear went through. Like those whose names surround him, Jesus preached and pursued love and justice, ultimately laying down his life—a loss that God turned to gain in the Resurrection and in the redemption of the world.

A language barrier prevented me from effectively asking the staff person, or understanding the answer, whether the crucifix was carved in the early 2000s specifically for the chapel, or if it’s medieval. There’s no info inside the church about this chapel.

The Memorial for the Martyrs of Today is an example of what Christian martyrdom looked like in Cologne in the twentieth century. Fr. Otto Müller, Br. Norbert Maria Kubiak, writer Heinrich Ruster, medical student Willi Graf, Catholic Youth leader Adalbert Probst . . . The stories of the many individuals who were executed for subverting Hitler, for calling out his evils, in the name of Christ are far more compelling to me than the fabulous and convoluted story of an ancient princess killed in a land invasion and then heroized—for her virginity?

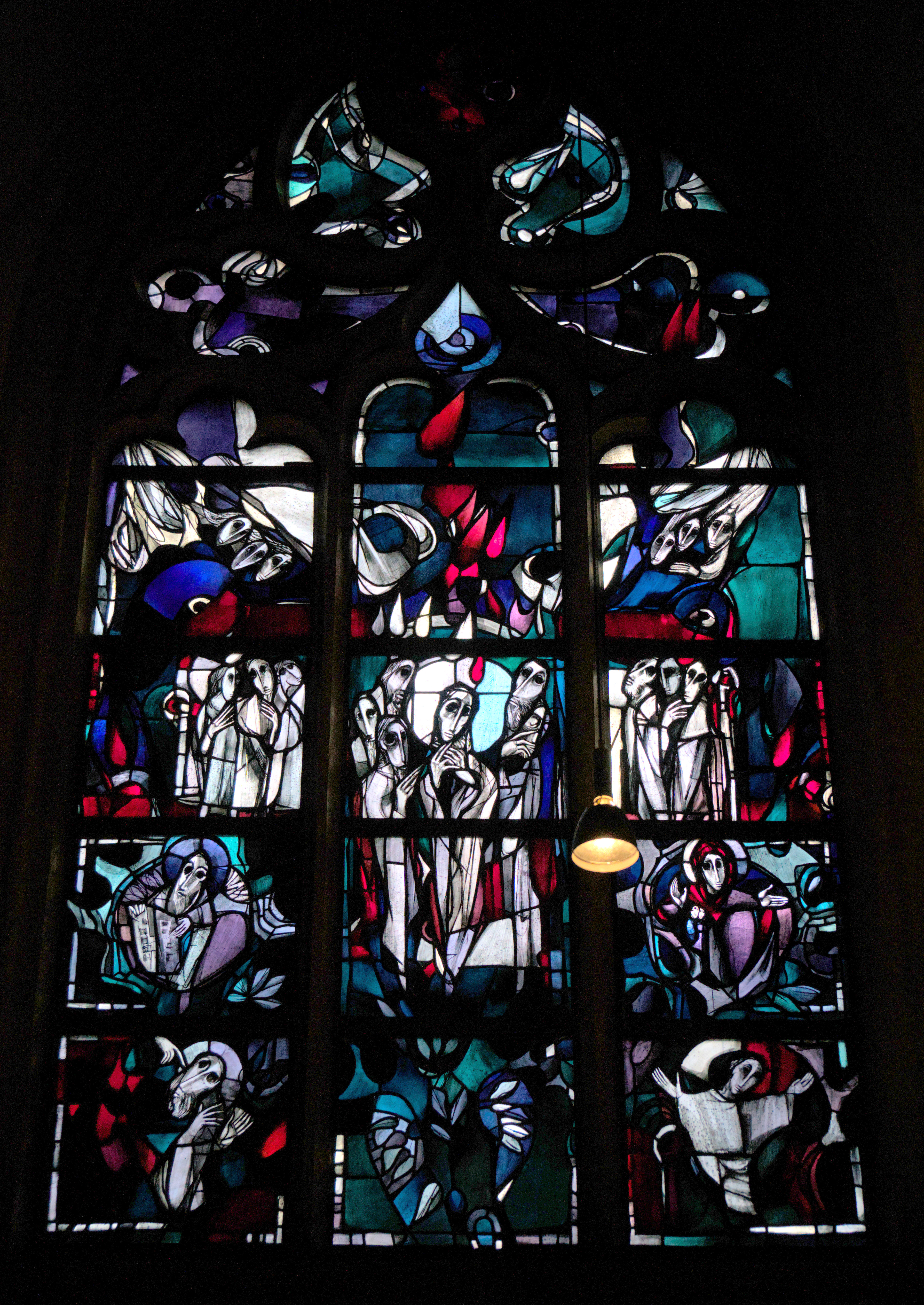

Contemporary Stained Glass

I also liked the contemporary stained glass in the church. In the choir, there’s a set of eight windows by Wilhelm Buschulte—abstract compositions in yellow, white, and gray.

In the south aisle are two round-arched windows by Will Thonett, also abstract: a grid of blues, grays, and lavender, with yellow circles and thin vertical bands.

To the right of these are three Mary-themed windows by Hermann Gottfried. The primary scene of the first one is the Annunciation. A giant red rose appears in the background, probably a reference to Mary as the Rosa Mystica. Below this scene, to the left, is the Creation of Adam and Eve, and to the right, the Expulsion from Paradise; these contextualize Christ’s conception in the greater narrative of scripture. The peripheral scenes in the middle register show the magi following the star to Bethlehem.

The central window portrays the Coronation of Mary. I believe both figures in the left lancet are Christ—crowning his mother as Queen of Heaven, and at the bottom, crushing the serpent, as the protoevangelium in Genesis 3:15 prophesied. Beneath the enthroned Mary on the right is a smaller vignette, which I think may be Mary again, also stepping on the serpent’s head, since by her cooperation with God’s plan, she shares in the victory over Satan. This imagery is also related to Woman of the Apocalypse described in Revelation 12, whom Catholics interpret as Mary. The hand of God dispenses blessing from above.

The final window in this trio portrays the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. The two quadrants at the bottom right show Moses before the burning bush, in which Mary appears; Catholic teaching compares Mary to the burning bush of Exodus because for nine months she held the fire of divinity within her womb (God incarnate) and was not consumed. On the left Moses is receiving the tablets of the law on Mount Sinai, an event often read in parallel with the story of Pentecost in Acts 2, where God writes his word not on stone but on people’s hearts by giving his Spirit to dwell within them.

If you’re ever in Cologne, I encourage you to include the Basilica of St. Ursula on your itinerary. Entry to the church is free, but the Golden Chamber costs €2 (only cash is accepted, I believe). There are six large standing posters in the narthex that provide a timeline, in German, of the church’s history, and when I was there, there were two attendants who were available to answer questions, one of whom spoke some English.

For more comprehensive photos of the church’s art and architecture, see https://www.sakrale-bauten.de/kirche_koeln_st_ursula.html and https://www.winckelmann-akademie.de/wp-content/uploads/Koeln_St._Ursula.pdf.