WORLD PREMIERE: “Yr Oedd Gardd / There Was a Garden” by Alex Mills, March 29, 2024, Saint Deiniol’s Cathedral, Bangor, Wales: On Good Friday this year, a new setting of seven unpublished R. S. Thomas poems, curated from the archives of the R. S. Thomas Research Centre, will be performed for the first time by Saint Deiniol’s Cathedral Choir under the direction of Joe Cooper, accompanied by devotional readings. The choral composition is by Alex Mills [previously], and it was commissioned by Saint Deiniol’s for Holy Week. The title comes from John 19:41–42: “Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.”

Thomas was a priest in the Church of Wales and one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets, his works exploring the cross, the presence and absence of God, forgiveness, and redemption.

This is the second commission Mills has fulfilled for the cathedral; last year he wrote “Saith Air y Groes / Seven Last Words from the Cross,” a choral setting of the seven short phrases uttered by Jesus from the cross, according to the Gospel writers, but in Welsh.

+++

CONTEMPORARY HYMNS/GOSPEL SONGS BY WOMEN:

I try to be intentional about featuring the work of women throughout the year, but as March is Women’s History Month, I wanted to call attention to these three sacred songs by Christian women from the generation or two before me.

>> “Christ Jesus Knew a Wilderness” by Jane Parker Huber (1986): Born in China to American Presbyterian missionaries, Jane Parker Huber (1926–2008) is best known as a hymn writer and an advocate for women in the church. This hymn—which can be found in A Singing Faith (1987), among other songbooks—is particularly suitable for Lent. Huber wrote the words, pairing them with an older tune by George J. Elvey. Lucas Gillan, a drummer, educator, church music director, composer, and occasional singer-songwriter from Chicago and founding member of the jazz quartet Many Blessings, arranged the hymn and performs it here with his wife, Anna Gillan, a project commissioned by Saint Matthew Lutheran Church in Walnut Creek, California. What a great violin part!

Christ Jesus knew a wilderness

Of noonday heat and nighttime cold

Of doubts and hungers new and old

Temptation waiting to take holdChrist Jesus knew uncertainty

Would all forsake, deny, betray?

Would crowds that followed turn away?

Would pow’rs of evil hold their sway?Christ Jesus knew an upper room

An olive grove, a judgment hall

A skull-like hill, a drink of gall

An airless tomb bereft of allChrist Jesus in our wilderness

You are our bread, our drink, our light

Your death and rising set things right

Your presence puts our fears to flight

>> “For Those Tears I Died (Come to the Water)” by Marsha Stevens-Pino (1969): I grew up in an independent Baptist church in the southern US, and though the worship music consisted almost entirely of traditional hymns, I have a faint recollection of a woman singing this song as an offertory one Sunday. (Or maybe I heard it on a Gaithers’ television special at my grandma’s house?) It is a very early CCM (contemporary Christian music) song that was popular with the emerging Jesus Movement. Marsha Stevens-Pino (née Carter) (born 1952) of Southern California wrote it in 1969 when she was sixteen and a brand-new Christian, and it was recorded by Children of the Day in 1971.

In the video below, excerpted from the DVD Stories and Songs, vol. 1, it is sung by Callie DeSoto and Maggie Beth Phelps with their father, David Phelps.

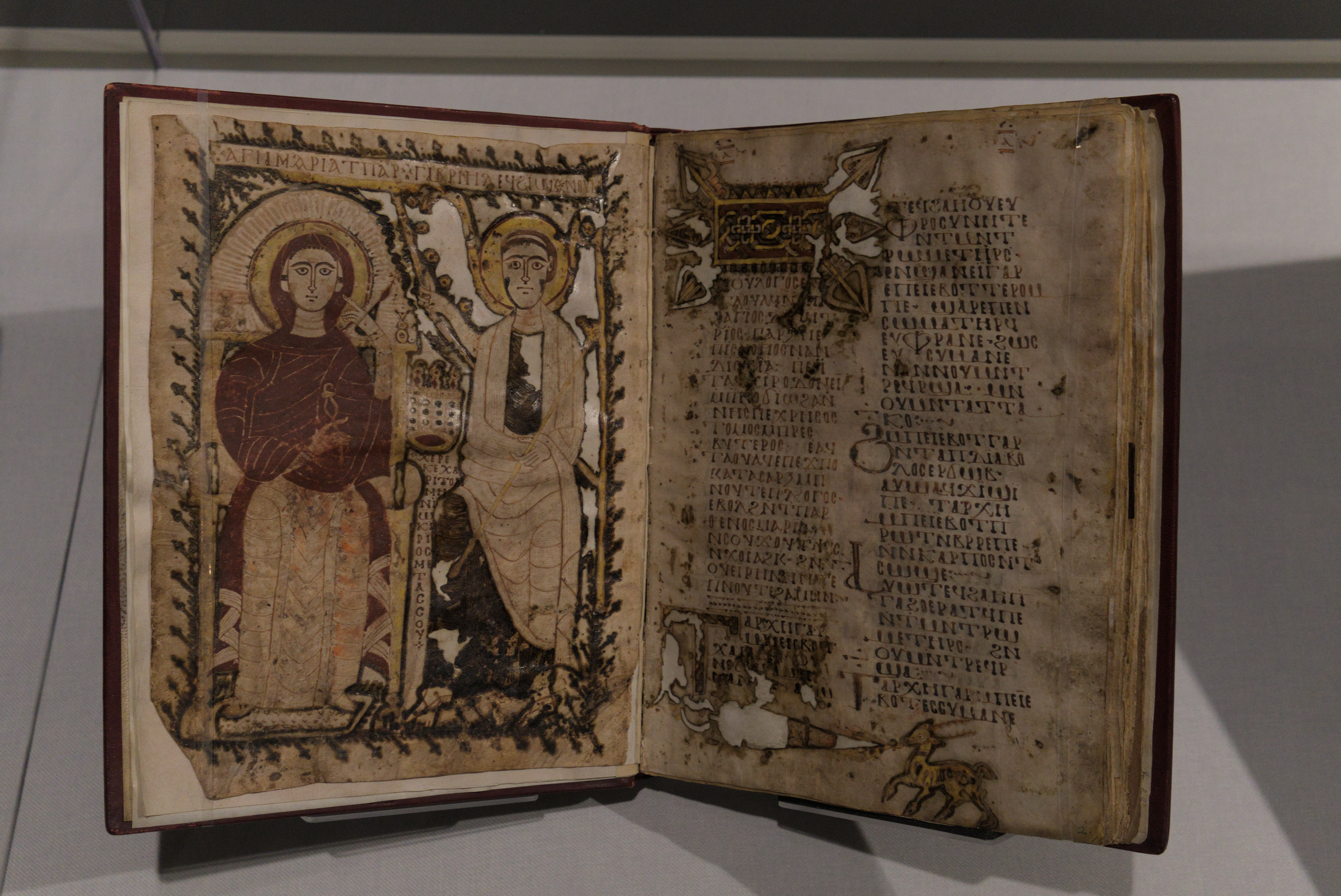

>> “The First One Ever” by Linda Wilberger Egan (1980): An alumna of the Union Theological Seminary School of Sacred Music with a background in voice and organ, Linda Wilberger Egan (born 1946) has served Lutheran, United Methodist, and Presbyterian congregations as music director throughout her career. Based on Luke 1:26–38, John 4:7–30, and Luke 24:1–11, her hymn “The First One Ever” honors the gospel witness of biblical women: Mother Mary, who said yes to God’s plan for her life, bearing the Messiah into the world; the unnamed woman of Samaria, who, after Jesus personally revealed his messianic identity to her, evangelized her whole village; and Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James, the first people to receive the news of Jesus’s resurrection and to preach it to the apostles.

The hymn is sung in the following video by Lauren Gagnon at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Chenango Bridge, New York, accompanied by her husband, Jacob Gagnon, on guitar.

+++

SUBSTACK POST: “St. Gabriel to Mary flies / this is the end of snow & ice” by Kristin Haakenson: Kristin Haakenson, creator of Hearthstone Fables, is an artist, farmer, and mom from the Pacific Northwest who shares art and reflections inspired by the sacred and the seasonal, place and past. In this most recent post of hers, she discusses the yearly intersection of Lent and the Feast of the Annunciation. “In a time when the Annunciation isn’t celebrated as universally within the Church as it once was, it may feel somewhat disjointed to stumble upon this joyful feast – celebrating the conception of Jesus – during the penitential season of Lent,” she writes. “This timing, though, is part of a revelatory harmony within the Christian calendar. When we step back to see it in the context of the rest of the liturgical year – and also in the context of the natural, astronomical seasons – the theology embedded in this system of sacred time begins to absolutely bloom.”

+++

LITURGICAL POEM: “Annunciation 2022” by Kate Bluett: Kate Bluett from Indiana writes metrical verse around the liturgical calendar and is also one of the lyricists of the Porter’s Gate music collective. In this poem (which she said was inspired in part by the timing of this blog post!) she brings the Annunciation into conversation with the Song of Solomon in such resonant ways.

On Holy Saturday I’m planning to feature a song that connects the Song of Solomon to the women at Jesus’s tomb! If you haven’t read that Old Testament book or it’s been a while, I’d encourage you to do so, as then you’ll be able to more easily identify the references in Bluett’s poem and the upcoming song I’ve scheduled for the Paschal Triduum.