Anyone who cries at night, the stars and the constellations cry with him.

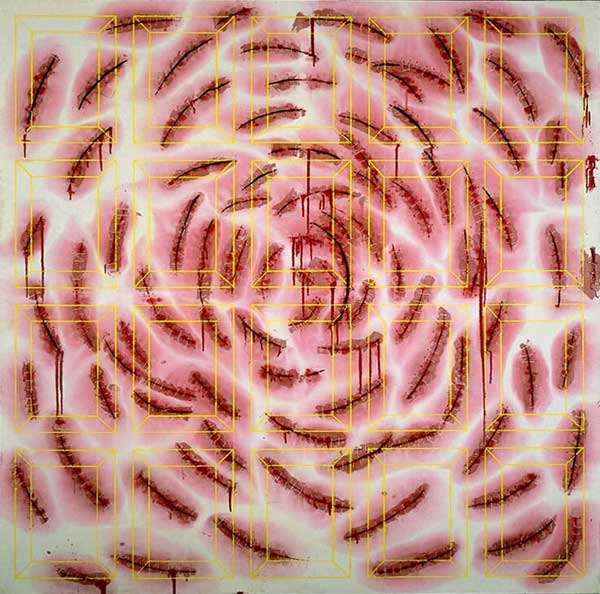

LOOK: Blood and Tears by Hélène Mugot

When Jesus went out to the garden of Gethsemane to pray the night of his arrest, he pled with the Father to let the cup of suffering pass. Luke says he sweated drops of blood (22:44). He was in agony. He probably dreaded the physical torture he knew was coming, and maybe even more his disciples’ abandoning him. Perhaps he wept for the mother and friends he would leave behind in this next phase of ministry—or, with a mixture of grief and frustration, for the world’s failure to see who he truly was.

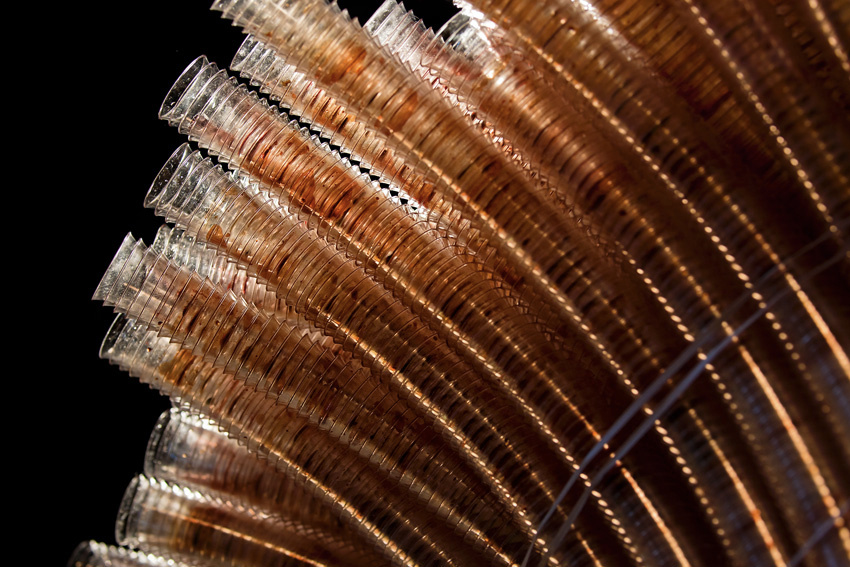

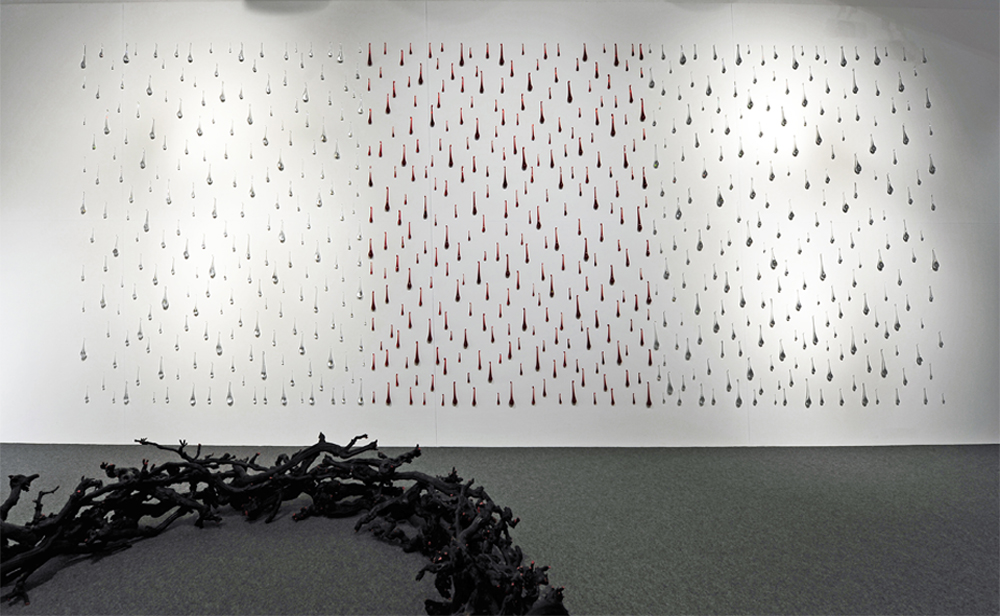

Hélène Mugot’s Du sang et des larmes, which translates to Blood and Tears, is an installation of glass pieces made to look like bodily fluids. They hang on the wall in the shape of a three-paneled altarpiece—blood in the center, tears on the wings. The globular forms catch the light from the room and shine.

When Du sang et des larmes was exhibited at the Mandet Museum in 2011, it was part of a larger show of Mugot’s work. On the floor in front of it was her Pour la gloire… (For the Glory…), a menacingly large braided wreath of thick, knotted, blackened vines whose stumps are dotted with red wax of the type used to seal wine bottles—both bandage and wound here, Mugot says. The piece is meant to evoke Jesus’s crown of thorns.

In 2013 Du sang et des larmes joined the collection of the Musée du Hiéron in Paray-le-Monial, France, a museum of Christian art from the Middle Ages to today. There it is staged as the backsplash to a seventeenth-century Virgin and Child statuette carved in wood, thus prompting us to read Christ’s infancy in light of his passion, and vice versa—the Incarnation as a total event, spanning birth to death. (Cue Simeon’s “A sword will pierce your soul . . .”)

To fit the space, the number of droplets and overall size changed slightly from the piece’s first few installations: at the Hiéron there are 311 crystal drops and 267 red glass drops, and the dimensions are 420 × 650 cm.

LISTEN: “Flow, My Tears” by Toivo Tulev, 2007 | Text based on a 1600 air by John Dowland and the Improperia (aka, the Reproaches), a series of antiphons and responses expressing the remonstrance of Jesus Christ with his people | Performed by the Latvian Radio Choir, dir. Kaspars Putniņš, on Tulev: Magnificat, 2018

Flow, my tears,

fall from your springs,

flow my tears, fall from your . . .

Flow my tears,

fall from your springs,

fall, fall, fall,

flow, flow, my tears, flow.Down, vain lights,

shine no more,

no nights are dark enough,

no lights,

shine no more,

flow no more,

no more.

Flow down, vain lights,

shine no more,

shine you no more.I led you in a pillar of cloud

but you led me to . . .

I gave you saving water,

but you gave me gall

and you gave vinegar.

My people, what have I done to you?

What have I done to you? Answer me.

How have I offended you, you, you?

I opened the sea before you,

I opened the sea,

but you opened my side with a spear.Flow, flow, flow down.

Rain, drop down,

cover the ground,

drop down, my blood,

flow, flow down,

drop down,

drop down, drop,

flow, flow, flow,

shine, flow, flow, shine!

Flow, my blood, flow,

flow, drop, flow down.My blood spills from your wounds,

drop, drop, drop,

your wounds,

flow, flow, flow down,

flow, shine, drop, flow.

Flow my tears, fall from your springs,

flow, my blood.

My blood, my blood spills from your wounds,

my wounds,

my blood,

flow, blood, flow, flow,

shine!

Spills from your wounds

my blood, shine!

My wounds, my wounds,

drop down, shine!

From your, from my wounds,

shine!

Flow, drop down,

shine!

Flow, shine!

My, your blood,

shine!My blood,

flow, shine, flow,

shine! shine!

Fall, shine, fall, shine,

fall from your . . .

flow, fall . . .

Shine!

Shine! [source]

Toivo Tulev is an Estonian composer born in 1958. In this choral composition for twelve solo voices, he has combined words from a secular Renaissance lute song and the Christian Holy Week liturgy. It’s ponderous and grating, capturing well Jesus’s psychological affliction.

While in the first half the speaker, Jesus, wishes for light to “shine no more” so that he be left alone in darkness, that imperative eventually evolves into the affirmative: “Shine!” Blood: shine! Tears: shine! Tulev’s clever manipulation of his lyrical source material creates allusions to the glory, the illumination, that is to come. Paradoxically, when the sun is eclipsed from noon to three on the day of crucifixion, God’s love shines brighter than ever.

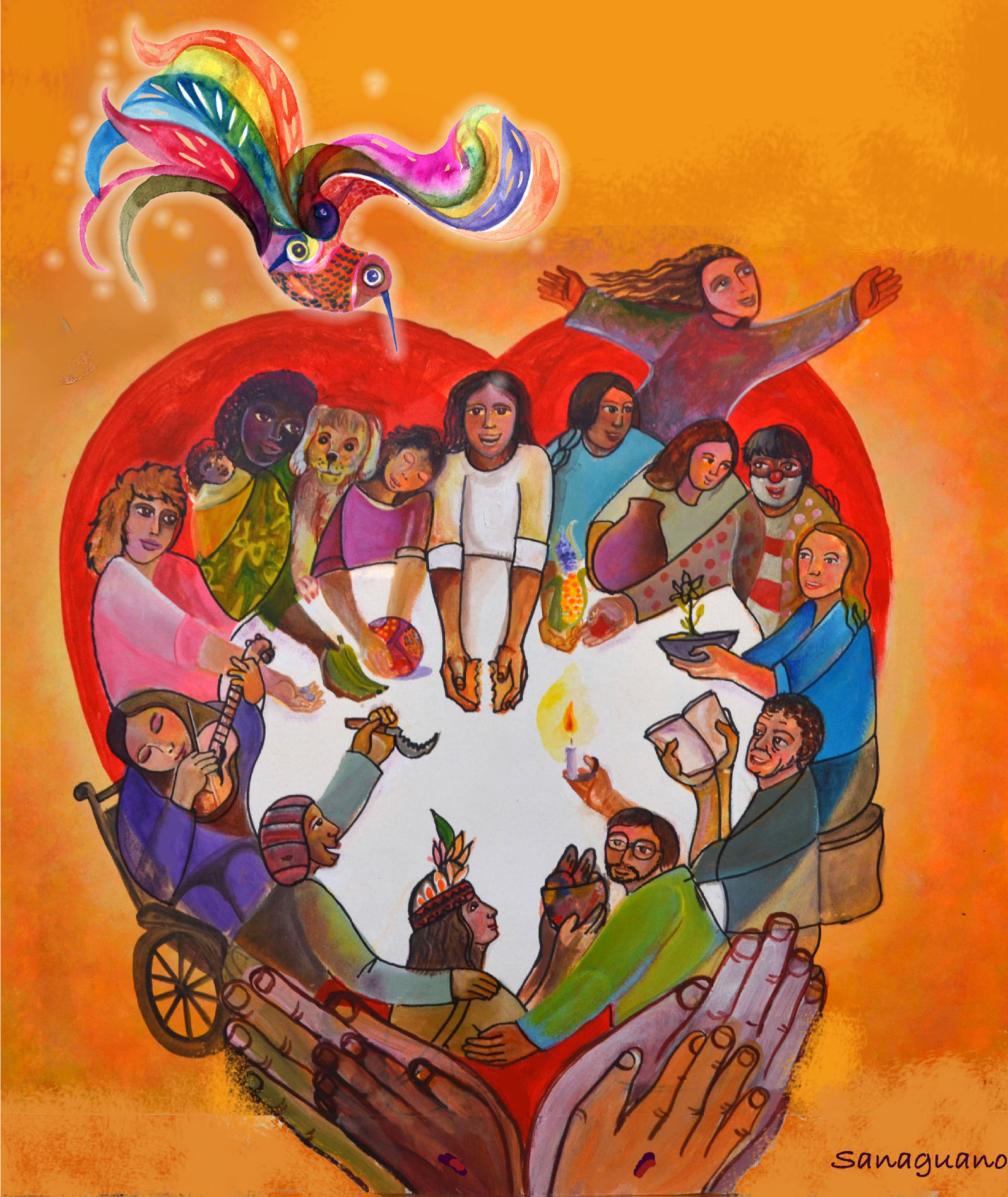

One line that stands out to me is “My blood spills from your wounds.” Who is the “your”? Earlier Jesus is talking to his people, but I interpret a shift here to God the Father as the addressee. Even though he sees through to the other side, he, too, is tremendously pained by what is unfolding—his only Son, killed. It’s as if Jesus’s wounds are his own (much like any parent would tell you, when their child is suffering). The unity of these two persons of the Godhead in the poetry of this song is really beautiful. Their heart is one.