February is Black History Month, and while I endeavor to showcase Black art year-round, today’s post gives it dedicated attention.

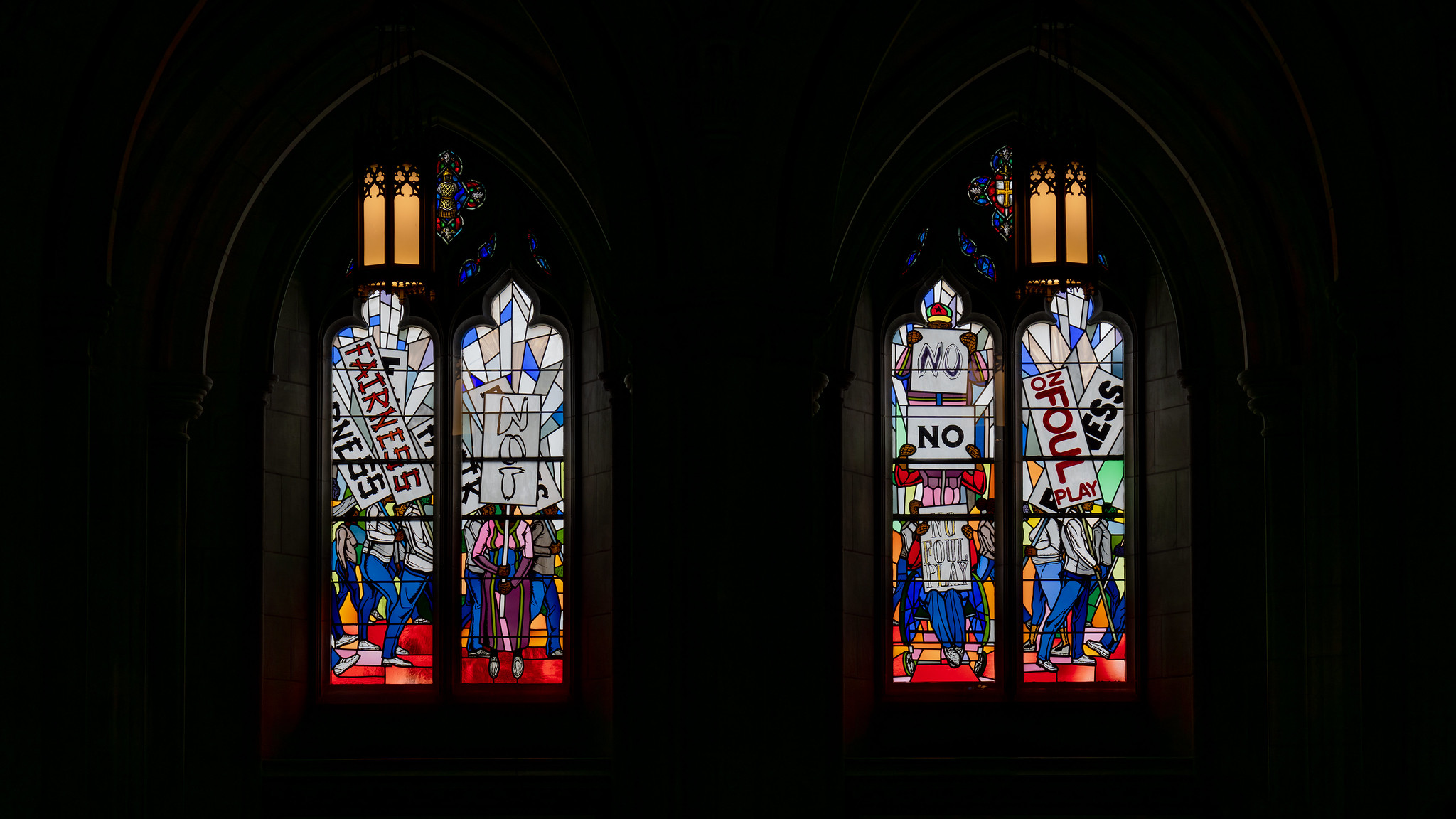

VIDEO: “Kerry James Marshall, Now and Forever; Elizabeth Alexander, ‘American Song,’ Washington National Cathedral,” Smarthistory, January 22, 2024: Art historian Beth Harris and Kevin Eckstrom, former chief public affairs officer of Washington National Cathedral, explore the latest artwork to be permanently installed in the US capital’s “house of prayer for all people”: two Now and Forever stained glass windows by Kerry James Marshall, depicting a march for racial justice. Unveiled on September 23, 2023, these replace windows that memorialized Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, which had been donated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and installed in 1953. (For my international readers: The Confederacy was a group of eleven Southern US states that seceded from the Union in 1860 and 1861 to preserve the institution of race-based chattel slavery on which their plantation economies relied; its government was dissolved in 1865 following the end of the Civil War, but its legacy continued.)

In 2015, when a white supremacist, who touted the Confederate flag as symbolic of his ideology, murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, Washington National Cathedral’s dean at the time, the Very Rev. Gary Hall, called for the removal of the Lee-Jackson windows, which initiated a two-year discernment process involving ample community discussions. The cathedral finally took down the windows in 2017 following a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that claimed yet another life. The Very Rev. Randolph Hollerith, then the dean, said the windows “were a barrier to our mission, and an impediment to worship in this place.” Their removal and the installation of the Now and Forever windows in their place were funded by private foundations.

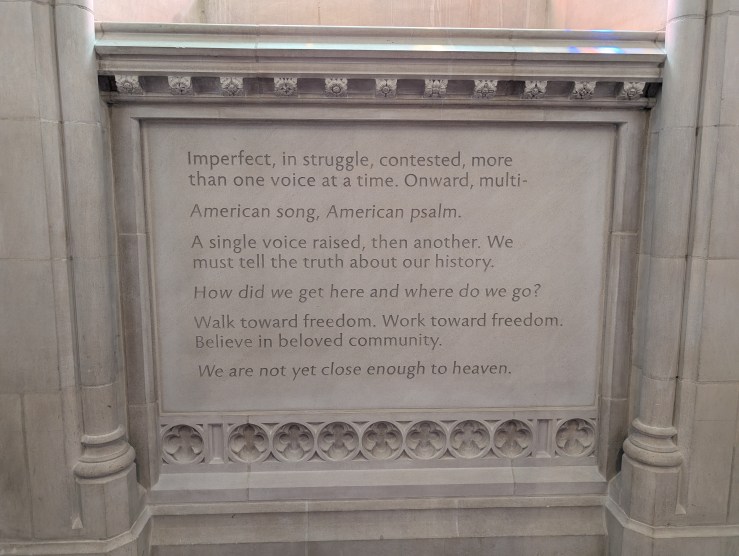

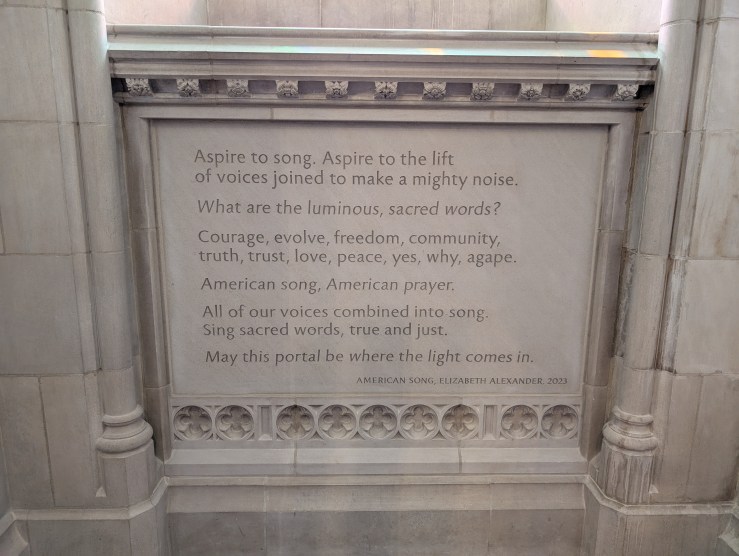

In addition to commissioning Marshall to design new windows, the cathedral commissioned the Pulitzer-nominated poet Elizabeth Alexander, who wrote and read “Praise Song for the Day” for President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration, to write a poem for this occasion. Titled “American Song,” it is inscribed on two limestone tablets beneath Marshall’s windows. The Windows Replacement Committee gave both artists this assignment:

We seek to tell a story of resilience, endurance, and courage that gives meaning and expression to the long and arduous plight of the African American, from slavery to freedom, from alienation to the hope of reconciliation, through physical and spiritual regeneration, as we move from the past to present day. The artist will capture both darkness and light, both the pain of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow, as well as the quiet and exemplary dignity of the African American struggle for justice and equality and the indelible and progressive impact it has had on American society. Each artist should respond in his or her own creative way to these ideals and aspirations, framing both the earthly and the divine, within the sacred space of the Washington National Cathedral.

When I was there last year, I asked the guide why the signs the figures hold don’t bear any of the more familiar slogans of our historical moment, such as “Black Lives Matter.” She said the artist deliberately did not want to tether the protest to a particular time period, in order to emphasize that the struggle for racial equality is ongoing. “Fairness,” “No Foul Play,” “No,” “Not”—these are expressions of demand and defiance that could apply to a number of justice-related issues and that encompass people of all races.

Learn more at https://cathedral.org/college/windows/.

+++

DANCE: “Still I Rise,” choreographed by Sean Cheesman: I really miss the TV show So You Think You Can Dance, which had aspiring dancers train across genres—contemporary, hip-hop, ballroom, jazz, etc.—with renowned choreographers, performing to compete for the title of “America’s favorite dancer.” It was entertaining, impressive (the athleticism!), and often moving. Here’s a contemporary routine choreographed by Sean Cheesman to spoken word artist Alexis Henry’s reading of a classic poem by Maya Angelou about Black strength and defiance. It’s danced by Koine “Koko” Iwasaki, Kiki Nyemchek, Taylor Sieve, and Mark Villaver. It’s from season 14, episode 12, which aired September 4, 2017.

(Another memorable Cheesman-choreographed dance from season 14 is an African jazz duet to Sheila Chandra’s “Speaking in Tongues II,” which unfortunately, I cannot find online.)

+++

ARTICLE: “Stephen Towns’ Quilted Works Emphasize Black Joy as Resistance in ‘Safer Waters’” by Kate Mothes: Through June 14, the Wichita Art Museum in Kansas is hosting the exhibition Safer Waters: Picturing Black Recreation at Midcentury, featuring eleven quilts and six paintings by the Baltimore-based artist Stephen Towns [previously]. Black history has always been an important aspect of Towns’s work, and in this series he was inspired by historic photographs (by Bruce Mozert) of Paradise Park, a segregated attraction in Silver Springs, Florida, that operated from 1949 to 1969 and that was popular among Black vacationers, providing a space for leisure and togetherness away from Jim Crow.

Towns began his Paradise Park series in 2022 after reading Remembering Paradise Park by Cynthia Wilson-Graham and Lu Vickers, and this show is a continuation of it, for which he made seven new quilts (pictured in Mothes’s article). His art is displayed alongside some of Mozert’s photographs and related objects from Florida archives and collectors. See an exhibition walk-through on the artist’s Instagram page; see also photos from the opening on January 16–17.

Here is a short 2024 interview with Towns about this body of work, as presented at the earlier exhibition Private Paradise: A Figurative Exploration of Black Rest and Recreation at the Rockwell Museum in Corning, New York:

+++

SONGS:

Gospel music is one of the many gifts the Black church has given the world. Here are two songs from that distinctive choral tradition.

>> “Perfect Praise (How Excellent)” by Brenda Joyce Moore, performed by the Sunday Service Choir: Written in 1989 based on Psalm 8, this song gained recognition through its performance on the 1990 album This Is the Day by Walt Whitman and the Soul Children of Chicago, featuring Lecresia Campbell. It has since become a gospel choir standard, though often with the lead vocals eliminated (and that part taken by the full choir). It’s performed in this video by Sunday Service at the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in Paris on March 1, 2020.

>> “He’s a Wonder” by Jamel Garner, performed by the Chicago Mass Choir, feat. Cornelius Owens: This song about Jesus’s miracles is from the Chicago Mass Choir’s 2024 album Greater Is Coming.

+++

PODCAST EPISODES:

>> “Artist Archetypes with Jakari Sherman,” Be. Make. Do., January 21, 2025: I really enjoyed this conversation with Jakari Sherman on the soul|makers podcast hosted by Rev. Lisa Cole Smith, where he describes his journey as an artist and a believer. Sherman is a choreographer within the tradition of stepping, a percussive dance practice in which dancers use primarily their hands and feet to create music. Stepping comes from the African American Greek letter organizations and has roots, Sherman explains, in the antebellum South, where enslaved people had their drums taken away and thus had to find ways to express the rhythms they felt using just the floor and their own bodies. (Tap evolved largely for the same reason.)

Sherman is the creative director of [Jk]creativ, a multidisciplinary company developing purpose-driven and truth-seeking cultural works. From 2007 to 2014 he served as the artistic director of Step Afrika! and has continued to develop and direct works for them, such as Drumfolk and The Migration (which I saw in 2024 and was excellent). To establish a foundation for his scholarly research on the history of stepping, he completed a master of arts program in ethnochoreology at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance in 2015. Below is a trailer for one of Sherman’s latest works, Our Road Home, an interactive rhythmic production that meditates “on what is means to find freedom—and to live it fully in body, soul, and spirit”; it premiered last June as part of a year-long collaboration with the Houston Freedmen’s Town Conservancy.

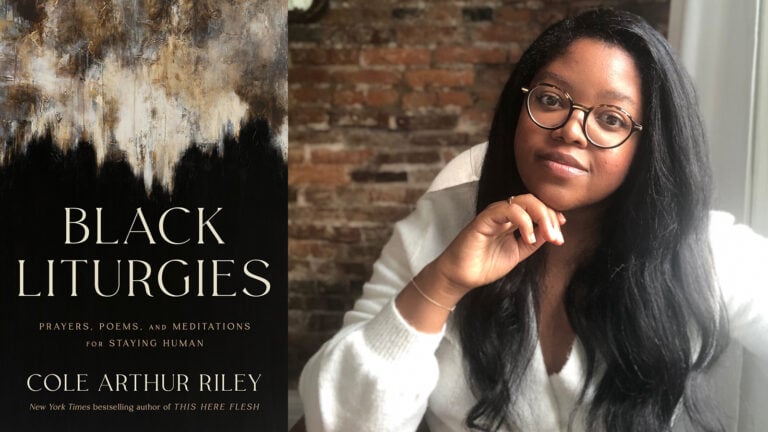

>> “Cole Arthur Riley – Black Liturgies,” Nomad, February 9, 2024: Tim Nash interviews Cole Arthur Riley, the best-selling author of Black Liturgies: Prayers, Poems, and Meditations for Staying Human (which grew out of her popular Instagram account @blackliturgies) and This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us. She is a wise, feeling, richly spiritual and embodied writer and speaker whose work I’ve appreciated. In this conversation she discusses her hang-ups with the Book of Common Prayer; battling chronic illness; balancing the active and contemplative lives; the revival of lament; self-sacrifice versus self-care; her experience of white people engaging with her work (“I like to think that there’s something mysterious that’s healed in us when we encounter each other’s interior worlds; when we hear words written by a Black woman toward God, that that could somehow move someone in some way, and move us closer to each other”); and what hope means to her and where she sees signs of it.

Even though I, as a white person, am not the intended audience for the book Black Liturgies, in reading it, I found it meaningful to listen to the cries of Riley’s heart. While many of the prayers are particular to the experience of being Black, still many others are general enough that they could be prayed by anyone. Part 1, organized thematically, consists of chapters such as “Dignity,” “Wonder,” “Doubt,” “Lament,” “Rage,” and “Rest,” whereas part 2 contains prayers for dawn, day, and dusk as well as for the liturgical year, secular holidays, and life occasions. I like the names for God with which she opens each prayer—e.g., “God of the shadows,” “God who expands,” “Divine Labyrinth,” “God aware,” “God of locked doors,” “God who reclaims,” “God our home,” “God of delight,” “God of the art that will never be seen,” “God who whispers”; it has prompted me to consider the names and descriptions I use for God and how they influence how I pray.

To give you a flavor of Black Liturgies, here are two prayers from the book (and note that prayers are only one component; also included are letters, quotes, questions for contemplation, confessions and assurances of pardon, and benedictions):

For Marveling at Your Own Face

God of the flesh,

When we consider what is worthy of our wonder, it is easy to forget our own faces, our bodies. The world is relentless in indoctrinating us into self-hatred—into anti-Blackness, into transphobia, into misogyny in all forms. We are slowly and steadily brainwashed to despise our own faces from the time we’re tall enough to stare up at ourselves in the mirror. How can we resist this? Let the tyranny of the mirror be no more. May it instead become a portal—to delight, to pleasure, and to love. These noses, these hips, the way our hair rises and falls. The memories etched into our hands and faces. Remind us of the miracle of flesh that grows back, of blood that pulses warm beneath the skin that holds us. Of bodies, these holy beautiful bodies, that are working a thousand unseen miracles just so that we can read these lines, breathe this air, cry or not cry. As we peer into the face before us, remind us that we are something to behold. We believe; forgive our unbelief. Ase.

For Those Who Doomscroll

Still God,

We confess that we are addicted to pessimism. Although we rarely name it as such, so much of our attention is devoted to negativity. Show us how we use technology to soothe and stir the aches in us. Keep us from turning control over to our anxiety, that it would no longer feed itself with news of tragedy and impending disaster. It is easy to become lost, buried in the quicksand of digital catastrophe. Draw our attention upward. Guide us to look away habitually; and not just away, but up at the sky, the grass, the table. Guide us inward as well. Acquaint us with goodness again. In the world, and in ourselves. Let us follow the children, freed from the grip of seriousness. Renew our playfulness. Lead us into wise rhythms of engagement, retreating to rest and breathe. Remind us that there is much the world needs, including our attention to atrocity—but if we watch the world burn for long enough, the fire will become our only reality. Amen.