Let’s say you’re visiting London. You buy a ticket to the Tate Modern, because hey, the tourist guides call it a must-see. You enter the enormous Turbine Hall and witness, across the five-hundred-foot downward concrete ramp that is the floor, a giant crack. No, it’s not a foundation problem. It’s a contemporary art installation by Doris Salcedo.* What in the world does this artwork have to offer? How do you engage meaningfully with it?

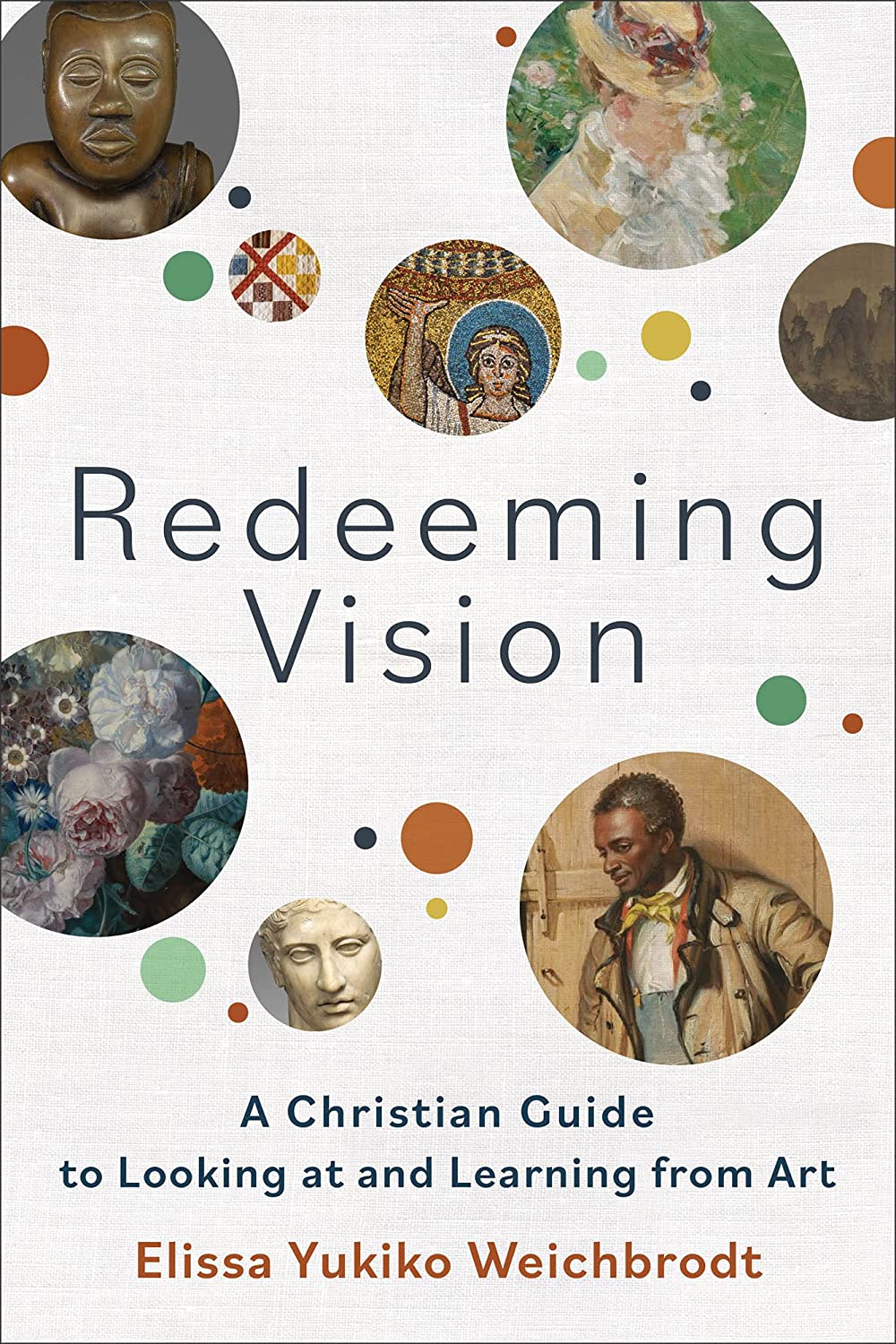

Dr. Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt’s book Redeeming Vision: A Christian Guide to Looking at and Learning from Art (Baker Academic, 2023) equips Christians to look closely and well—with a posture of humility and generosity—at works from across the spectrum of art history, including ones like Salcedo’s Shibboleth that may initially evoke only puzzlement or an eye roll, and others that may at first glance seem run-of-the-mill and uninteresting (a marble head, a vase of flowers, an old family photograph). When we close ourselves off to art that doesn’t immediately touch us, we reject potential opportunities for transformation, transformation of how we see and how we love. Regardless of the personal faith commitments of its makers, Weichbrodt says, art can grow our love for both God and neighbor.

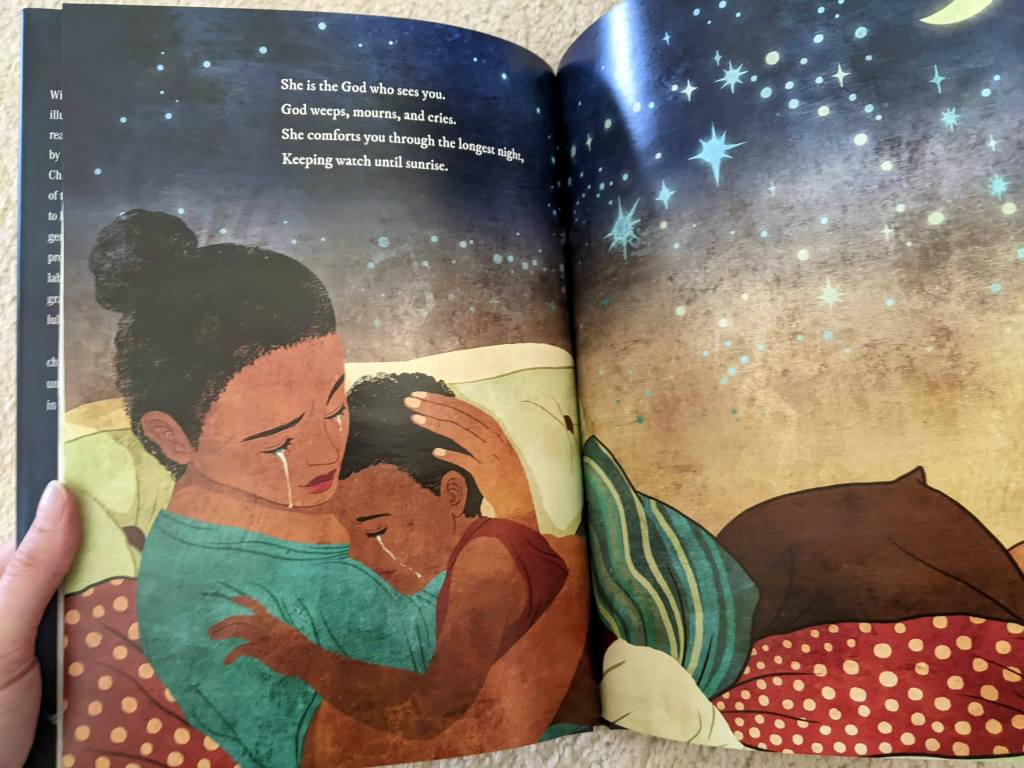

In order to love, we must first look. Weichbrodt gives examples of God’s looking in scripture to establish a “model of redemptive looking,” which “is utterly different from the objectifying gaze that is so common in our contemporary culture. Too often we look to consume, to surveil, to control, and to condemn. But as the beloved of God, we are called to mimic his gaze” (19). What if instead of letting personal judgments, stylistic, moral, or otherwise, dominate our approach to art, we were to adopt a primary posture of love?

When it comes to viewing art and visual culture, our faith doesn’t offer us a fence. It provides a path.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt, Redeeming Vision, p. 10

Weichbrodt wants to move us beyond a facile thumbs-up or thumbs-down approach to looking at art, encouraging us to press in to unfamiliar (and too-familiar!) or even off-putting works with curiosity and openness, asking questions of them and allowing them to interrogate us as well. What stories, and whose stories, do the images tell and not tell?

She introduces the notion of “the archive,” the mental collection of images we have seen, which we subconsciously file into categories and access to help us interpret new images. Some examples of categories are “Mother,” “Poor,” “Black,” “Beautiful,” “Villain.” The problem is, our archives are inherently limited. For example,

Why do we have so many mental images of mothers in Africa living in poverty and so few mental images of successful, smiling African women who are business owners and community leaders? Why do we have so many images in our archive of good white mothers and so few of loving, strong, generous Latina mothers? A richly textured, robust, and varied archive is necessary if we are going to learn to see others—of all races, ethnicities, genders, and social classes—as God sees them. (62)

Expand your archive, Weichbrodt urges.

She demonstrates how archives work through a brilliant engagement with Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), an iconic photograph that I remember studying in a high school American history class but which Weichbrodt really opened up for me.

Weichbrodt is an associate professor of art and art history at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. Besides an intro-level Western art survey course, she also teaches courses such as “Race in American Art and Visual Culture,” “Women, Art, and Culture,” “Art and the Church,” “Grace in American Art,” “History and Theory of Photography,” “Global Modernisms,” and “Contemporary Art and Theory.” The facility with which she’s able to guide nonspecialists deeper into her subject is amply evidenced in this book, which is low-shelf academic, geared toward educated readers who may or may not have an art background.

The most illuminating analyses in Redeeming Vision have to do with race, gender, and/or class; those are the topics where Weichbrodt’s primary research interests lie, and it’s where she really shines. She complexifies images that we might be inclined to take at face value, not think much about.

A highlight of the book is how Weichbrodt joins together fine art and contemporary visual culture more broadly, drawing Instagram selfies, memes, advertisements, news photos, propaganda posters, and such into conversation with paintings, sculptures, and other artworks that you’re likely to find in a museum. The tools she provides for performing visual analysis—chapter 1 unpacks that toolbox, giving us language (and a handy chart!) for describing an image’s visual qualities—can be applied just as well to a friend’s iPhone photo as to a multimillion-dollar oil painting that’s been the subject of multiple monographs.

As would any art historian, Weichbrodt emphasizes the importance of understanding artworks within their historical contexts; “even if we can’t find all the answers, we should remember to ask questions about the image or object’s original audience and purpose” (62). But where she differs from some academics in the field is that she also acknowledges that our backgrounds—who we are, what we aspire to be, what experiences we carry with us, our cultural conditioning—are not irrelevant to the process of looking at art. She invites us to take stock of associations that come up for us in response to certain images, not to make them an authoritative lens but to prompt queries that bring us closer to truth. We need to recognize the limitations of how we see, but we need not get ourselves entirely out of the way when it comes to art, as if pure objectivity were even possible.

In Weichbrodt’s discussion of specific artworks, I appreciate the balance of attention between the work’s formal qualities, content, historical situatedness, and meaning. She also reminds us to consider a work’s physical context. In chapter 3, for example, she uses Caravaggio’s Deposition to discuss the differences between experiencing an artwork in situ (that is, in the place for which it was created; in this case, a chapel), in a museum, and online—and what questions to ask in each situation.

Chapters 4–10 each conclude with a “For Further Looking” page that lists artworks related to the theme of the chapter and offers guided questions. For example, in chapter 9, “Allowing for Complexity: Art of the Everyday,” the “For Further Looking” section includes the headings “Nineteenth-Century American Genre Painting” (How do these works reinforce certain gender roles or racial hierarchies?), “Genre Works by Black American Artists” (How do these works celebrate the normalcy of Black life and achievement?), and “The History of the Female Nude in Western Art” (How have artists borrowed, developed, and critiqued this trope?). I found these end-of-chapter sidebars to be incredibly helpful, quenching my desire for wider exploration and deeper reflection.

Some of the topics Weichbrodt covers in the book include:

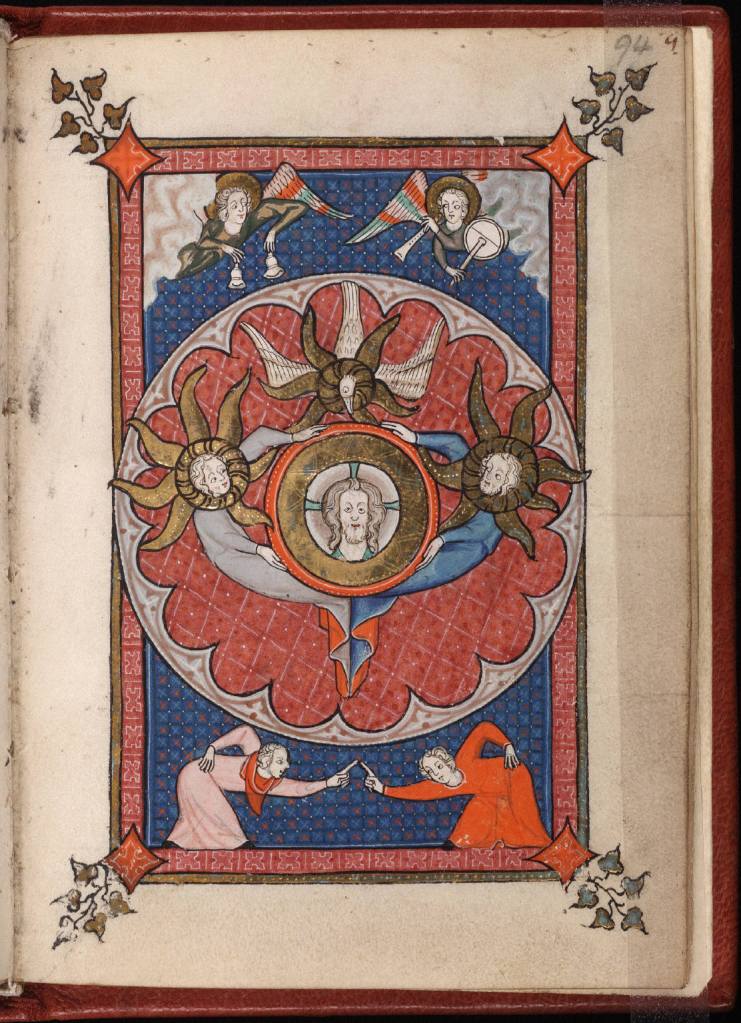

God’s Transcendence. In chapter 5 she contrasts a medieval church mosaic, with its golden resplendence, placed above the head to an abstract expressionist painting by Kandinsky, an explosion of color and movement and indefinable forms—two very different ways, and over a millennium apart, to convey the same idea.

Portraiture. In chapter 7 she addresses the possibilities and pitfalls of the portrait genre. From a Spanish count-duke to a Kuba nyim (king) from Central Africa to the anguished Vincent van Gogh to a mourning Missouri father with his two daughters and nurse, Weichbrodt discusses the physical self, the symbolic self, the public self, the private self, and the relational self. She also comments on how the portraits we see of others on social media shape our self-perception and self-representation.

Landscape. In chapter 8 she considers humanity’s relationship to nature by looking at two mountain views: a Chinese ink on silk from the Northern Song Dynasty, influenced by the principles of Confucianism, and a painting of the American West made during the era of westward expansion.

Weichbrodt encourages us to think critically about the stories we tell through images. Take, for example, this before-and-after photograph of Hastiin To’Haali, a resident of the federally funded Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1879–1918) in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which gutted me:

Founder Richard Henry Pratt hired the commercial photographer John Choate to document the residential school’s so-called success in “kill[ing] the Indian, . . . sav[ing] the man,” as Pratt put it, and these are two of the hundreds of photos he took of the students. What do we do when images lie?

One of my favorite chapters in the book is chapter 10, “Learning to Lament: The Art of History.” Here Weichbrodt discusses an ancient Assyrian stone relief carving of a soldier conducting captives across a river, a widely distributed revolutionary-era engraving of the Boston Massacre by Paul Revere, and From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried by Carrie Mae Weems (1995).

“History is not simply a documentation of the past,” Weichbrodt writes. “It is the story we tell about past events. What do we include? What gets left out? Who has our empathy? Who can be vilified?” (215). She continues:

What stories do we weave about who we are and who we are not? Does our telling of history—and the images we use to support it—ignore brokenness in favor of self-congratulation? What are the images and objects that direct us to lament? We lament not to wallow in despair or guilt or recriminations but because we have the freedom to weep as children of God. Ours can be a productive grief. (232–33)

Hospitable, expansive, and full of insight, Redeeming Vision helps Christians identify the ways in which images form us and teaches us how to skillfully analyze them. Art viewing, Weichbrodt writes, is not necessarily a passive activity; it requires something of us and can be generative. “Our gaze,” she says, “can open up something new” (11), leading to doxology, confession, empathy, understanding, lament, shared delight, or love.

Visit the book’s website at https://www.redeemingvision.com/. You can order a copy from Amazon or Baker Publishing Group, and sign up to participate in the guided chapter-by-chapter reading community that Weichbrodt is leading from August 28 to November 17, 2023. Follow her on Instagram @elissabrodt.

* This artwork is no longer on display; the crack was filled in in 2008.

Note: On November 11, 2023, the Eliot Society in Annapolis, Maryland, is hosting a lecture by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt titled “Rupture as Invitation: Generosity and Contemporary Art,” and I’ll be moderating the Q&A. I hope you can come out! Register here. (Update: Listen to the talk.)