The Rothschild Canticles is the name of a lavishly illuminated manuscript of Franco-Flemish origin, produced at the turn of the fourteenth century. “A potpourri of biblical verses, liturgical praise, dogmatic formulas, exegesis, and theological aphorisms, . . . the manuscript leads its user step by step through meditations on paradise, the Song of Songs, and the Virgin Mary to mystical union and, finally, contemplation of the Trinity,” describes Barbara Newman in her excellent essay “Contemplating the Trinity: Text, Image, and the Origins of the Rothschild Canticles.” It’s a diminutive little book, with a trim size of just four and a half inches by about three and a quarter.

The manuscript lacks any provenance before 1856, but Newman proposes that it was made at the Benedictine abbey of Bergues-Saint-Winnoc in Flanders, located at what is today the northern tip of France. The compiler of its texts, she suggests, was probably the same person who designed its remarkable images—most likely a monk of Saint-Winnoc, who probably employed a professional lay artist from Saint-Omer to execute the designs. The book’s patron was probably a canoness at the nearby abbey of Saint-Victor. It is now preserved at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. All photographs in this post are courtesy of the Beinecke. Click here to page through the fully digitized manuscript.

The most extraordinary section of the book is a florilegium (collection of literary extracts) on the Trinity, which comprises folios 39v–44r and 74v–106r and draws especially on Augustine’s De Trinitate. Within these pages are nineteen full-page miniatures that exhibit “the most stunning iconographic creativity, . . . bearing witness to a distinctive Trinitarian theology.”

The representation of the Holy Trinity poses one of the most difficult iconographic problems in Christian art. How is one to portray three distinct, divine persons who share one essence? Historical attempts have included the following:

- Three identical Christomorphic men (this one is relatively rare)

- Three mystically conjoined faces, or three separate heads sharing one body (nicknamed the “monstrous Trinity” and condemned by the Roman Catholic Church)

- The Gnadenstuhl (Throne of Mercy, or Throne of Grace), in which the Father is shown holding a crucifix or, in a later variation known as the Mystic Pietà, his slumped Son, while the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove hovers between them

- Triangles, trefoils, triquetras, or other abstract geometric designs that suggest Three-in-Oneness

- In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Holy Trinity is represented by three angels seated at a table. These are the three mysterious visitors of Abraham in Genesis 18, believed to be a theophany (visible manifestation of God).

The artist of the Rothschild Canticles relies on none of these conventions, inventing instead an almost wholly original visual language to express the rich yet daunting doctrine. In contrast to other depictions of the Trinity, in the Rothschild Canticles we find, says Newman,

a playful, intimate approach to the triune God, marked by spontaneity rather than solemnity, dynamism rather than hieratic stasis, wit rather than awe. There is no hint of narrative, but something more like an eternal dance. . . . The divine persons are caught up in an everlasting game of hide-and-seek with humans while they enact among themselves, in ever-changing ways, that mutual coinherence that the Greek fathers called perichoresis—literally “dancing around one another.” (135)

Jongleurs (itinerant medieval entertainers proficient in juggling, acrobatics, music, and recitation), angels, and various pointing figures play the role of implied viewers and manifest a joyous attitude. For example,

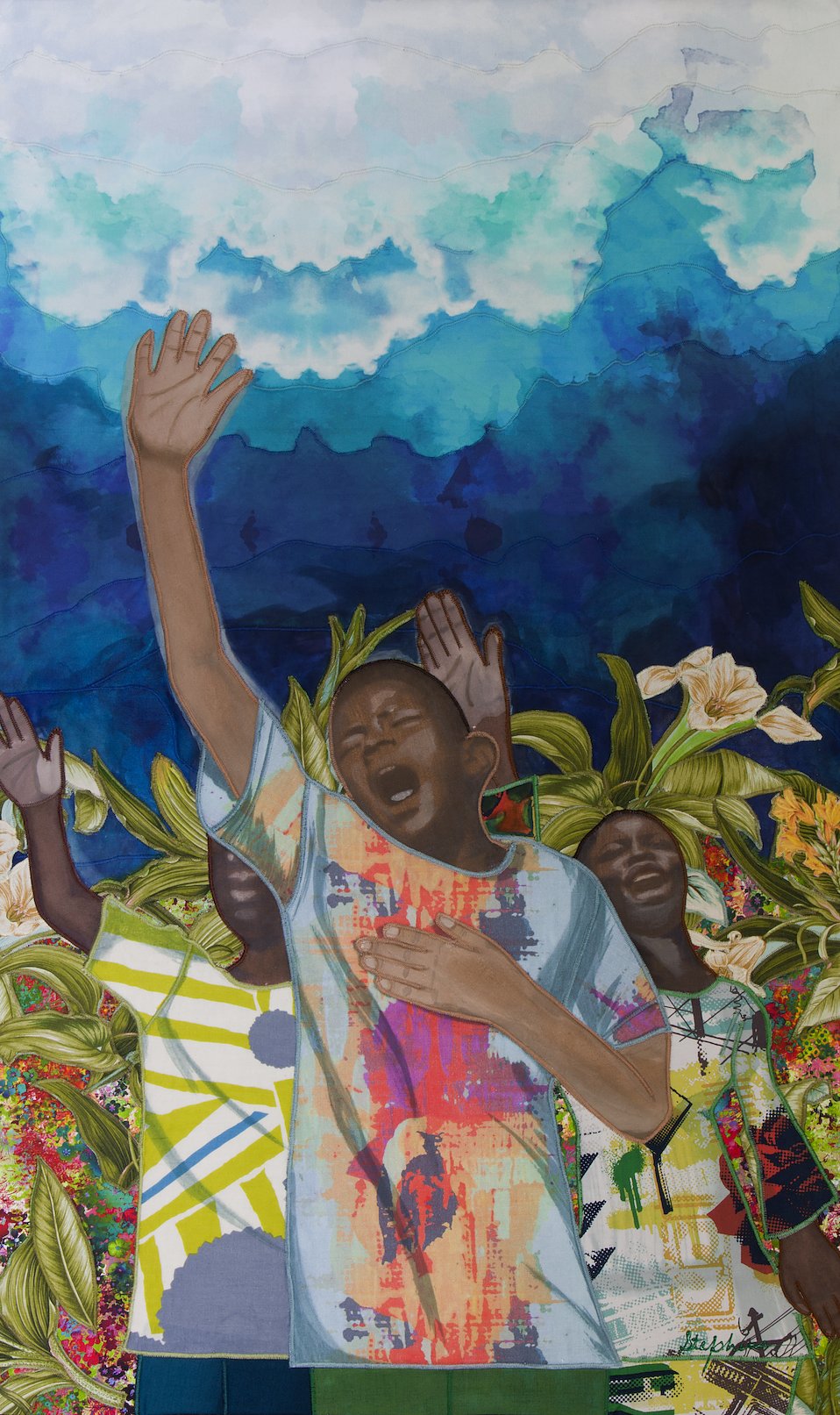

on fol. 79r a celestial percussionist attacks a row of bells with mallets; on fol. 84r, angels in the upper left and right play a game of ring toss; on fol. 88r, musicians . . . strum whimsically shaped zithers embellished with animal heads. . . . In the lower right corner of fol. 96r, an elfin figure bends over backward to play an instrument whose pinwheel shape mimics the great solar wheel behind which divine Wisdom hides. Four characters in the corners of fol. 98r stretch their arms as if to join hands in a cosmic dance, while on fol. 100r, three spectators raise their hands in wonder beneath a divine apparition, imitating the stunned postures of Peter, James, and John at the Transfiguration. . . . Collectively, they seem to proclaim that the reader need not be ashamed or afraid, even though all human attempts to comprehend the Trinity are comically inept. Nonetheless, she can merrily follow the Lord of the Dance. (135–36)

The quirkiness is so endearing!

Newman continues,

In the Rothschild Canticles, coinherence is the dimension of Trinitarian theology to which the artist seems most profoundly committed. The complex relationality of the three persons is conveyed through the delicate interplay of touch, gesture, and changing positions. Sometimes the Father and Son join hands; on fol. 104r they touch feet behind the wheel they hold. Sometimes they grasp the sides, wings, or talons of the dove, and sometimes they unite around a fourth figure representing the Divine Essence. (143–44)

Moreover,

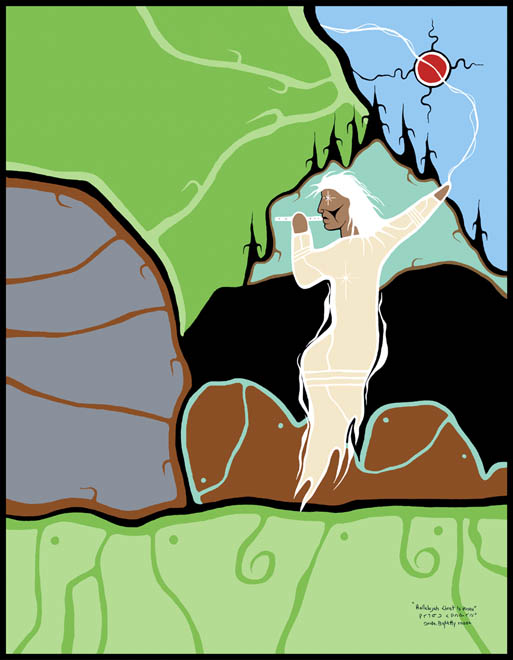

the artist invented some simple devices to keep the paradox of triunity before the mind’s eye at all times. For example, a prime signifier of divinity—the golden sun with its waving, tentacle-like rays—is sometimes single (fols. 44r, 81r, 88r, 90r), sometimes triple (fols. 40r, 83r, 94r). Elsewhere the artist complicated this formula. On fol. 79r, three small suns for each person are superimposed on one large sun; fols. 92r and 100r insert a smaller sun inside a bigger one; and on fol. 96r, two suns interlock to form a double wheel with spokes radiating both inward and outward. (141)

I particularly like fol. 94r, where the three persons of the Godhead wear the sun like a collar. And fol. 100r, where we see just three feet and three hands, each belonging to a different person, peeping out from behind a giant sun disc!

Another recurring and versatile motif in the Trinity cycle is the veil, which signifies both God’s presence and God’s hiddenness. Sometimes it forms a hammock in which the Trinity rests, partially covered (fols. 75r, 88r); or is braided in an enclosing circle, dangling down for humans to touch (fol. 81r); or is looped about the Father, Son, and Spirit, nestling them snugly (fol. 84r); or is knotted and clutched (fol. 92r); or is draped over bands of cloud (fol. 106r). In this artistic program, veils both conceal and reveal, communicating the paradoxical nature of God who is ensconced in mystery—incomprehensible—and yet accessible, wanting to be known.

Notably, the profusion of Trinitarian imagery is supplemented in the manuscript with textual reminders of the limitations of images. In De Trinitate 8.4.7, for example, Augustine says that all manmade images of God are false, and yet, he says, they are useful insofar as they help the mind cling to the invisible reality to which they point.

Below is a complete compilation of Trinity miniatures from the Rothschild Canticles, reproduced in the order they appear in the manuscript. I have prefaced most with one or more of the quotations that appear on its facing page (thanks to Newman’s identifications) so that you can see how intricately text and image relate. If you wish to reproduce any of these images singly, I suggest the following credit:

Trinity miniature from the Rothschild Canticles (MS 404, fol. _), made in Flanders, ca. 1300. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

“Dominus in orisunte eternitatis et supra tempus” (The Lord is on the horizon of eternity and beyond time):

“Tu es vere Deus absconditus” (Truly you are a hidden God) (Isa. 45:15):

“Bene ergo ipsa difficultas loquendi cor nostrum ad intelligentiam trahit, et per infirmitatem nostram coelestis doctrina nos adjuvat: ut quia in Deitate Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus sancti nec singularitas est, nec diversitas cogitanda, vera unitas et vera Trinitas possit quidem simul mente aliquatenus sentiri, sed non possit simul ore proferri.”—Pope Leo I, Sermo 76.2

(“This difficulty in expressing clearly by speech draws our hearts to the power of discerning, and, through our weakness, the heavenly doctrine helps us, that, because of the divinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, neither singularity nor diversity is to be considered. The true unity and true Trinity can be apprehended ‘at the same time’ by the mind, but cannot be produced at the same time by the lips.” Trans. Jane Patricia Freeland, CSJB, and Agnes Josephine Conway, SSJ)

“Pater complacet sibi in Filio et Filius in Patre, et Spiritus sanctus ab utroque” (The Father is well pleased in the Son, and the Son in the Father, and the Holy Spirit is from both):

“Dicebat enim intra se si tetigero tantum vestimentum eius salva ero” (She said within herself, if I touch the hem of his garment, I will be healed) (Matt. 9:21):

(Also illustrated on fol. 81r is the Holy Spirit as the person “qui facit ex utroque unum” [who makes both one; cf. Eph. 2:14], as cited on the facing page. Notice the shared halo.)

“Trinus personaliter et unus essentialiter” (Three in persons and one in essence):

“Dominus Deus noster Deus unus est” (The Lord our God is one God) (Mark 12:29):

“Ita et singula sung in singulis, et omnia in singulis, et singula in omnibus, et omnia in omnibus, et unum omnia. Qui videt hec vel ex parte, vel per speculum et in enigmate, gaudeat cognoscens Deum.”—Augustine, De Trinitate 6.12

(“They are each in each and all in each, and each in all and all in all, and all are one. Whoever sees this even in part, or in a puzzling manner in a mirror [1 Cor. 13:12], should rejoice at knowing God.” Trans. M. Mellet, OP, and Th. Camelot)

“Sapientia sua, que pertendit a fine usque ad finem fortiter et disponit omnia suaviter” (His wisdom, which reaches from end to end mightily and orders all things sweetly) (Wis. 8:1):

“Tres vidit et unum adoravit” (He saw three and worshipped one), a liturgical verse referring to the Trinitarian epiphany in Genesis 18:1–3, in which Abraham saw three men, fell down in worship, and then addressed his divine visitors in the singular:

“Gyrum caeli circuivi sola et in profundum abyssi penetravi et in fluctibus maris ambulavi” (I [Wisdom] have circled the vault of heaven alone) (Ecclus. 24:8):

“Abscondes eos in abdito faciei tuae” (Thou hidest them [the saints] in the covert of thy presence) (Psa. 30:21):

“Optime et pulcrius loquitur qui de Deo tacet” (He speaks best and most beautifully who is silent about God):

“Centrum meum ubique locorum, cirumferentia autem nusquam” (My center is in all places, my circumference nowhere). Also, “Quod Deus est, scimus. Quid sit, si scire velimus, / Contra nos imus. Qui cum sit summus et imus, / Ultimus et primus, satis est; plus scire nequimus.” (We know that God is; if we wish to know what he is, / We go against ourselves. That he is the highest and the lowest, / The last and the first, is enough; we can know no more.) And another: “Deus fuit semper et erit sine fine; ubi semper fuit, ibi nunc est. / Et ubi nunc est ibi fuit tunc.” (God always was and shall be without end; where he always was, there he is now. And where he is now, there he was then.)

(I love this detail of the Father and Son touching feet behind the wheel to brace themselves up! And the implosion of the sun.)

And lastly, the final text page in the Trinity cycle, which faces a nonfigural miniature of concentric rings of fire and cloud, contains this unidentified apophatic dialogue:

—Domine, duc me in desertum tue deitatis et tenebrositatem tui luminis, et duc me ubi tu non es.

—Mea nox obscurum non habet, sed lux glorie mee omnia inlucessit.

—Bernardus oravit: Domine duc me ubi es.

—Dixit ei: Barnarde, non facio, quoniam si ducerem te ubi sum, annichilareris michi et tibi.(—Lord, lead me into the desert of your divinity and the darkness of your light; and lead me where you are not.

—My night has no darkness, but the light of my glory illumines all things.

—Bernard prayed, Lord, lead me where you are.

—He said to him, Bernard, I will not, for if I led you where I am, you would be annihilated both to me and to yourself.)

My hope is that pastors, theologians, seminarians, and Christians in general spend time studying, meditating on, and delighting in these artworks, which present profound theological content in a compact and sensory format. Visual theology at its best.

Though our efforts to visualize the Trinity will always be clumsy and imperfect, I do think the Rothschild Canticles artist has been more successful than anyone before or since. His miniatures convey, with whimsy and warmth, the eternal relationship of love at the heart of the universe.

+++

WORKS CITED

Newman, Barbara. “Contemplating the Trinity: Text, Image, and the Origins of the Rothschild Canticles.” Gesta 52, no. 2 (Sept. 2013): 133–59.