SONGS: The following two songs appear on the Art & Theology Lent Playlist on Spotify. (Note: I’ve also integrated some Lovkn, Sarah Juers, and a few others into the list since originally publishing it.)

>> “Kyrie / Oh Death,” performed by Susanne Rosenberg: March 11 marks one year since the coronavirus outbreak was officially declared a pandemic, and the tremendous number of lives lost is staggering. (A friend from Japan reminded me that it’s also the ten-year anniversary of the Great Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that killed some 16,000 people; 3/11, he says, is as important in Japan as 9/11 is in the United States.) This lament by Susanne Rosenberg, one of Sweden’s foremost folk singers, seems appropriate. It combines a twelfth-century Kyrie chant with the Appalachian folk song “Oh Death,” the latter made famous by Ralph Stanley. Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Greek for “Lord, have mercy, Christ, have mercy,” is a short, repeated invocation used in many Christian liturgies, and Rosenberg seamlessly integrates it with these few lines: “Oh Death, oh Death, won’t you spare me over till another year?” The video recording is from a February 2010 concert in Dublin, and a similar version of the medley, in a different key, appears on Rosenberg’s album of the same year, ReBoot/OmStart.

>> “Washed in the Blood,” performed by Pokey LaFarge and Harry Melling: The Devil All the Time (2020) isn’t a great movie, but it has a great soundtrack. Harry Melling—known for his roles as Dudley Dursley in the Harry Potter series and, more recently, Harry Beltik in The Queen’s Gambit—plays a spider-handling preacher named Roy, and singer-songwriter Pokey LaFarge (whose style pulls from ragtime, jazz, country, and blues) plays his guitar-playing sidekick, Theodore. The two actors sing as their characters in the film, this classic hymn by Elisha Hoffman. Love it!

+++

SERMON: “Chagall at Tudeley” by Rev. James Crockford, University Church, Oxford, April 7, 2019: This sermon, preached on Passion (Palm) Sunday two years ago, is an excellent example of how pastors can draw on visual art as a theological and homiletical resource—not to merely illustrate a point already made or to add some pretty dressing to a sermon, but taking it on its own terms and allowing it to generate insight and guide the congregation someplace new. Crockford uses the East Window in All Saints’ Church in Tudeley, Kent, England, designed by the Russian Jewish artist Marc Chagall, to open up profound discussion on human loss, hope, renewal, and the cross. [HT: Jonathan Evens]

The window was commissioned by the parents of twenty-one-year-old Sarah d’Avigdor-Goldsmid, who in 1963 drowned off the coast of Sussex in a boating accident. “What I see in that East Window,” Crockford says, “is a remarkable exercise in the nature of suffering, and the interaction of human tragedy with the reality of Christ’s death and victory on the cross. It is a carefully composed centrepiece that asks us to face the depths of an abiding experience of grief, and to be faced with that grief each time we remember the grief of God, in broken bread and wine outpoured. But the window also shows a bigger picture – one that does not shut out the pains of our past, and the wounds in our hearts – and you’ll notice, when we come to it, that the scene of Sarah’s death still takes up over half of the window – but the bigger picture asks us to frame our grief and suffering on the centrality and promise of a God who, in Christ, is both suffering and victorious, broken and yet glorious, wounded but risen and standing among us to breathe Peace.” You can read the full transcript, or listen to an audio recording, at the link above.

+++

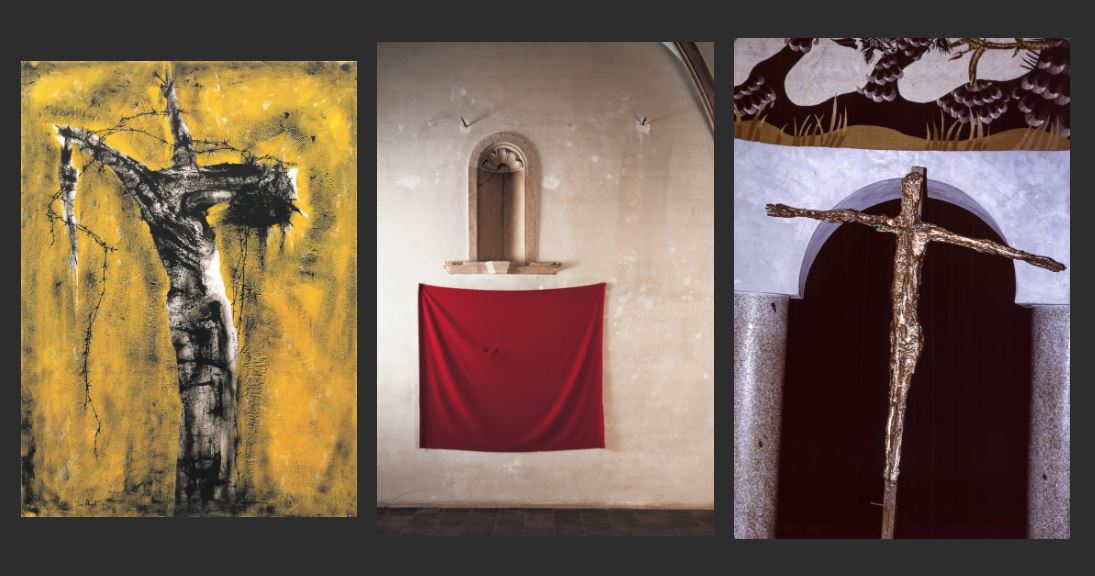

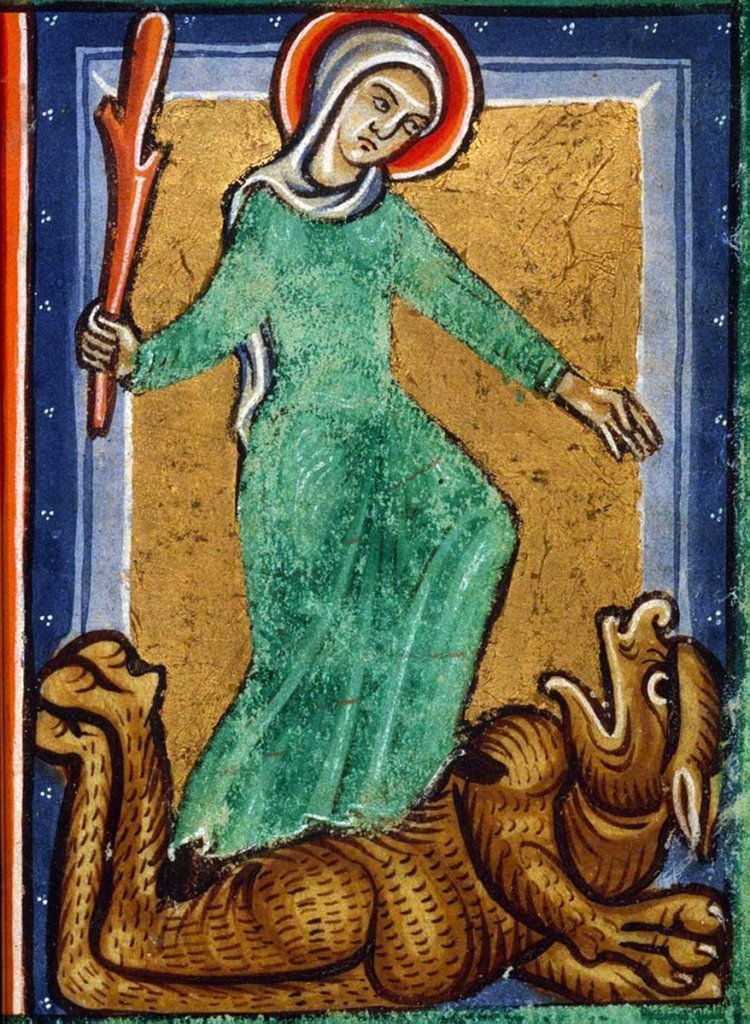

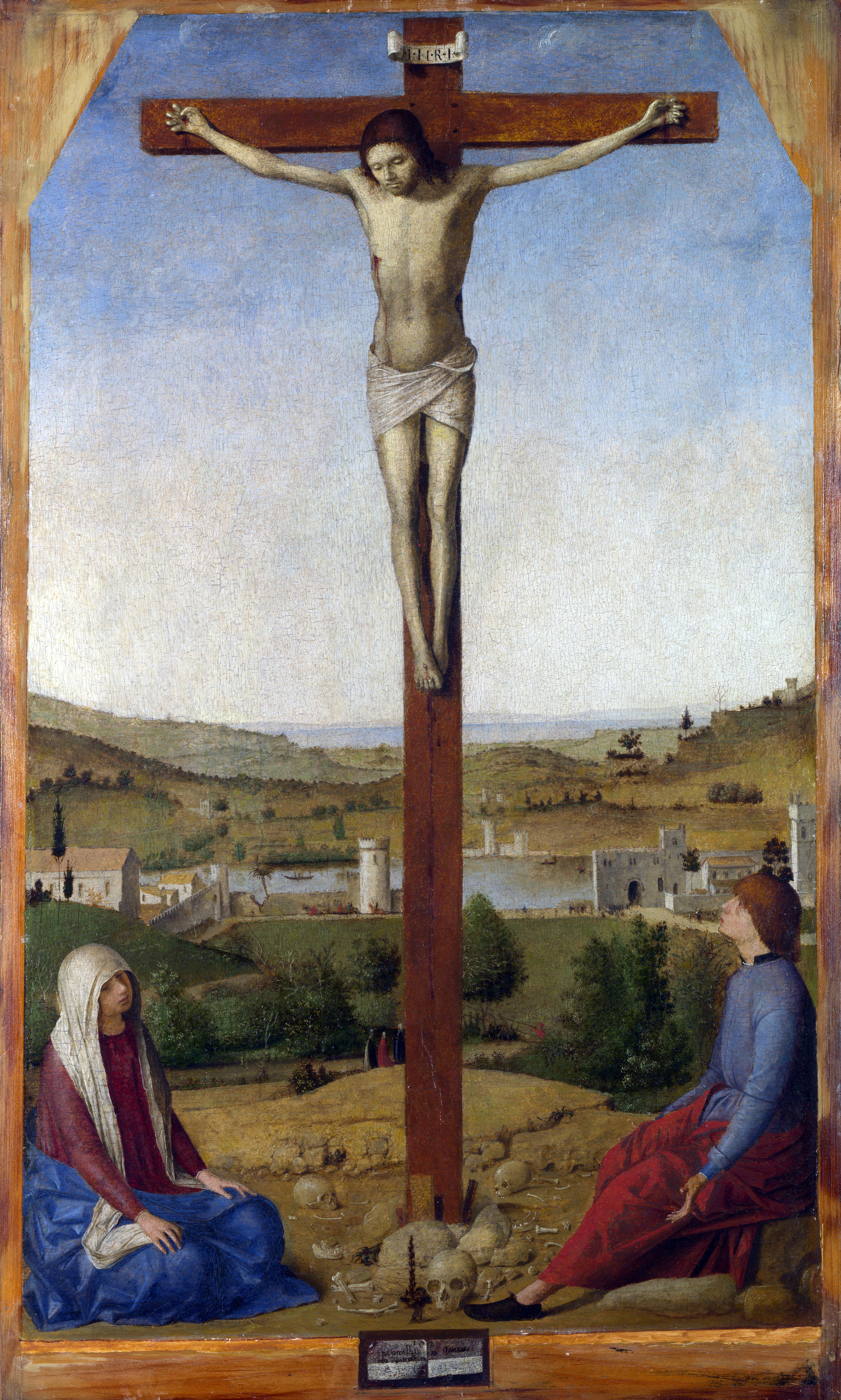

ART RESTORATION: “Hidden Gem: The Crucifixion by the Master of the Lindau Lamentation”: A Crucifixion painting from around 1425 by the Master of the Lindau Lamentation was recently restored by conservator Caroline van der Elst, and this short video documents part of that process. The Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, the Netherlands, acquired the painting in 1875, but since then it had lain mostly forgotten in storage until being rediscovered by a staff member a few years ago, who recognized it as a masterpiece worthy of restoration efforts and public display. After the surface dust and discolored varnish were removed, in addition to other treatments, it was unveiled last year as the centerpiece of the Body Language exhibition (check out that link!), which ran from September 25, 2020, to January 17, 2021.

Curators Micha Leeflang and Annabel Dijkema discuss how the painting was made, how it was originally used, and its theological significance, and van der Elst explains some of the conundrums she faced while restoring the work—when it came to light, for example, that the azurite background was added in the sixteenth century. View the full painting here.

+++

CALL FOR ARTISTS: Pass the Piece: A Collaborative Mail Art Project: A neat opportunity for artistic collaboration, organized by Sojourn Arts [previously] and open to US artists ages 13+. “Pass the Piece is a collaborative mail art project to be exhibited at Sojourn Arts in June 2021. Deadline for participating artists to sign up is March 31, 2021. Project is limited to 100 participants. We’re mailing out up to one hundred 8″ × 10″ panels, one to each participating artist. Each artist will start a panel that another artist will complete. Each artist will finish a panel that someone else started. Each artist will have their work exhibited and have a printed zine-style catalog of each piece from the exhibit. Artworks will be auctioned online with 50% going to the artists and 50% going towards Sojourn Arts interns’ travel expenses for the upcoming CIVA conference.”

+++

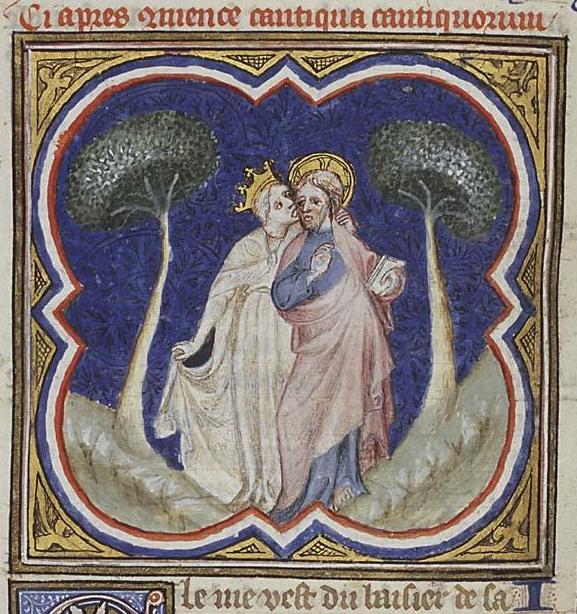

NEW ALBUM: for / waters by Joshua Stamper: Joshua Stamper [previously] composed this four-movement instrumental piece about marriage for pianist Bethany Danel Brooks and violinist David Danel, who are themselves married and perform on the recordings. Its title and that of each movement is taken from Isaiah 35, which was read at the couple’s wedding.

Stamper writes,

Marriage, ideally, is about two people in a state of mutual belonging. But marriage is more than a state of belonging: it includes an ongoing journey toward and into belonging. It encompasses the trajectories and momentum of individuals towards each other, even before an initial connection takes place. People are therefore in relationship with each other before they are “in relationship” with each other. From this perspective, marriage might be understood as another mystical manifestation of the inscrutable and unknowable fault line between free will and providence. Two lives are always in reference to one another before the initial “hello,” because though individual trajectories have not yet crossed, they will. This interweaving begins early: each life is conditioned, shaped, sensitized to see, hear, feel the other. Home is created in each for each.

Stamper goes on to describe how he reflects these ideas through the structure, melodic and rhythmic motifs, harmonies, and other musical elements of for / waters. Read more and stream/purchase at Bandcamp.

“Joshua Stamper has been a restless composer and collaborator for over twenty-five years. His work reflects a deep interest in the intersection points between seemingly disparate musics, and a profound love for the intimacy, charm, and potency of chamber music. Equally at home in the jazz, classical, avant-garde, and indie/alternative worlds, his work ranges from large-scale choral and instrumental works to art-pop song cycles to chamber jazz suites. Joshua has worked as an orchestral arranger and session musician for Columbia / Sony BMG and Concord Records, and for independent labels Domino, Dead Oceans, Important Records, Sounds Familyre, Smalltown Supersound, and Mason Jar Music, collaborating with such luminaries as Todd Rundgren, Robyn Hitchcock, Sufjan Stevens, Danielson, and Emil Nikolaisen.” [source]