All photos in this post, except for the last one (of the processional icon), are my own.

(Note: WordPress seems to have disabled the feature that allows you to expand an image upon clicking, but if you’re reading on a computer, you can right-click an image and open it in a new tab to view it in full resolution; if you’re reading on a phone, you can pinch to zoom.)

Located in the Horn of Africa and with access to the Red Sea, Nile River, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean, Ethiopia stands at the nexus of historical travel, trade, and pilgrimage routes that brought it into contact with surrounding cultures and influenced its artistic development. Coptic Egypt, Nubia, South Arabia, Byzantium, Armenia, Italy, India, and the greater African continent were among those influencers. But Ethiopia not only absorbed influences; it transmitted them too.

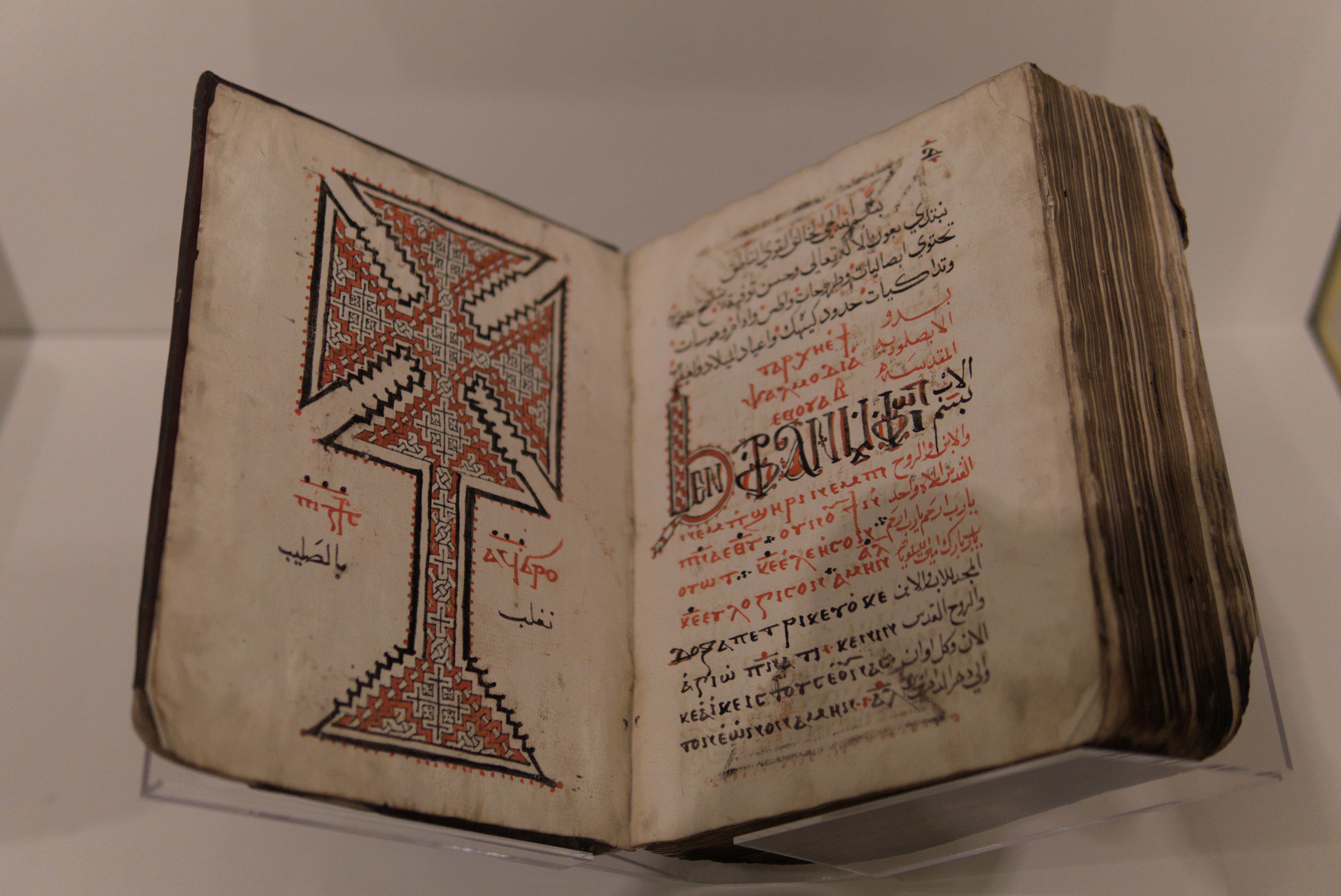

A major art exhibition is centering Ethiopia’s artistic traditions in a global context. For Ethiopia at the Crossroads at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (running through March 3), curator Christine Sciacca has brought together more than 220 objects from the Walters’ own extraordinary Ethiopian art collection and private and institutional lenders both domestic and international. Icons, wall paintings, processional crosses and hand crosses, illuminated Gospel books and psalters, sensuls (chain manuscripts), healing scrolls, and more are on display throughout the galleries, whose walls have been painted bright green, yellow, and red—the colors of the Ethiopian flag. To round off the exhibition, guest curator Tsedaye Makonnen, an Ethiopian American multidisciplinary artist, was tasked with curating a few works from contemporary artists of the Ethiopian diaspora.

The majority of objects are Christian, made for liturgical or private devotional use. Ethiopia is one of the world’s oldest Christian nations: in the early fourth century, persuaded by a missionary from Syria, King Ezana of Aksum embraced Christianity, and it has been the dominant religion of Ethiopia ever since. But the exhibition does also include some Islamic and Jewish objects.

One of the first works you’ll encounter is a mural that would have originally been mounted on the outer wall of an Ethiopian Orthodox church sanctuary (mäqdäs), portraying the Nativity, the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and the Adoration of the Magi.

Remarkably, at the Nativity, there is a feast taking place, and Jesus is feeding his mother with what looks like a Communion wafer! As the theologian Lester Ruth has said, “The sound from most baby beds is a cry to be fed. But the cry from the manger is an offer to feed on his body born into this world.”

One of history’s most famous Ethiopian painters is Fre Seyon, who worked at the court of Emperor Zara Yaqob (r. 1434–1468) and was of the first generation of Ethiopian artists who painted icons on wood panels. He was also a monk. He likely introduced one of the characteristic features of Ethiopian icons of the Virgin and Child: the archangels Michael and Gabriel flanking them with drawn swords, acting as a kind of honor guard.

My two favorite details of this triptych by Fre Seyon are (on the right wing) the image of the Ancient of Days surrounded by the tetramorph, his wild gray locks being blown about, and in the center, the bird that Christ holds, its feet grasping at a three-branched twig. On a literal level, the bird is a plaything for the boy that charmingly emphasizes his humanity (in the late Middle Ages, at least in Europe—I’m not sure about in Ethiopia—it was common for young children to keep tame birds as pets). On another level, the bird may be symbolic. In traditional Western art, Jesus sometimes holds a goldfinch, a bird with distinctive red markings that’s fond of eating thistle seeds and gathering thistle down and thus came to be read as a prefiguration of Christ’s thorny, blood-spilt passion. I’m not sure whether Fre Seyon intended a symbolic significance for this bird.

Here’s another triptych from the exhibition, this one from a century and a half later:

The composition of the Virgin and Child is based on prints of a painted icon from Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome brought to Ethiopia by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries—but it innovates. As the wall text notes, “Mary’s cloak stretch[es] out in either direction to embrace the scene of Christ Teaching the Apostles below. Umbrella-like, Mary appears as both the protector and personification of the church.”

On the right wing, angels hold up chalices to collect the blood that flows from Jesus’s wounds on the cross, while below that, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus carry Jesus’s wrapped corpse to the tomb. On the left wing is one of my favorite traditional religious scenes: the Harrowing of Hell, or Christ’s Descent into Limbo, in which, on Holy Saturday, Jesus enters the realm of his dead to take back those whom Death has held captive, first of which are our foreparents Adam and Eve. Below that scene is an image of the dragon-slaying Saint George, a late third-century figure from the Levant or Cappadocia who is the patron saint of Ethiopia.

At the bottom center is a scene of Christ teaching the twelve apostles, plus two Ethiopian saints. They all hold hand crosses, like those carried by Ethiopian priests and monks.

One of the hallmarks of the exhibition is its multisensory nature: attendees are immersed not only in the sights of Ethiopia but also in the sounds and smells. Scratch-and-sniff cards invite people to take a whiff of frankincense, which would have filled the censer on display. Or to smell berbere, a hot spice blend that would have been stored in the woven baskets nearby.

This olfactory element was produced by the Institute for Digital Archaeology, which, as part of its efforts to record and preserve ephemeral culture, has launched an ambitious program to preserve the heritage of smells. “The aim is to provide the technical means for documenting the aromas of today for the benefit of future generations – and to find new methods and opportunities for experiencing the odors of the past.”

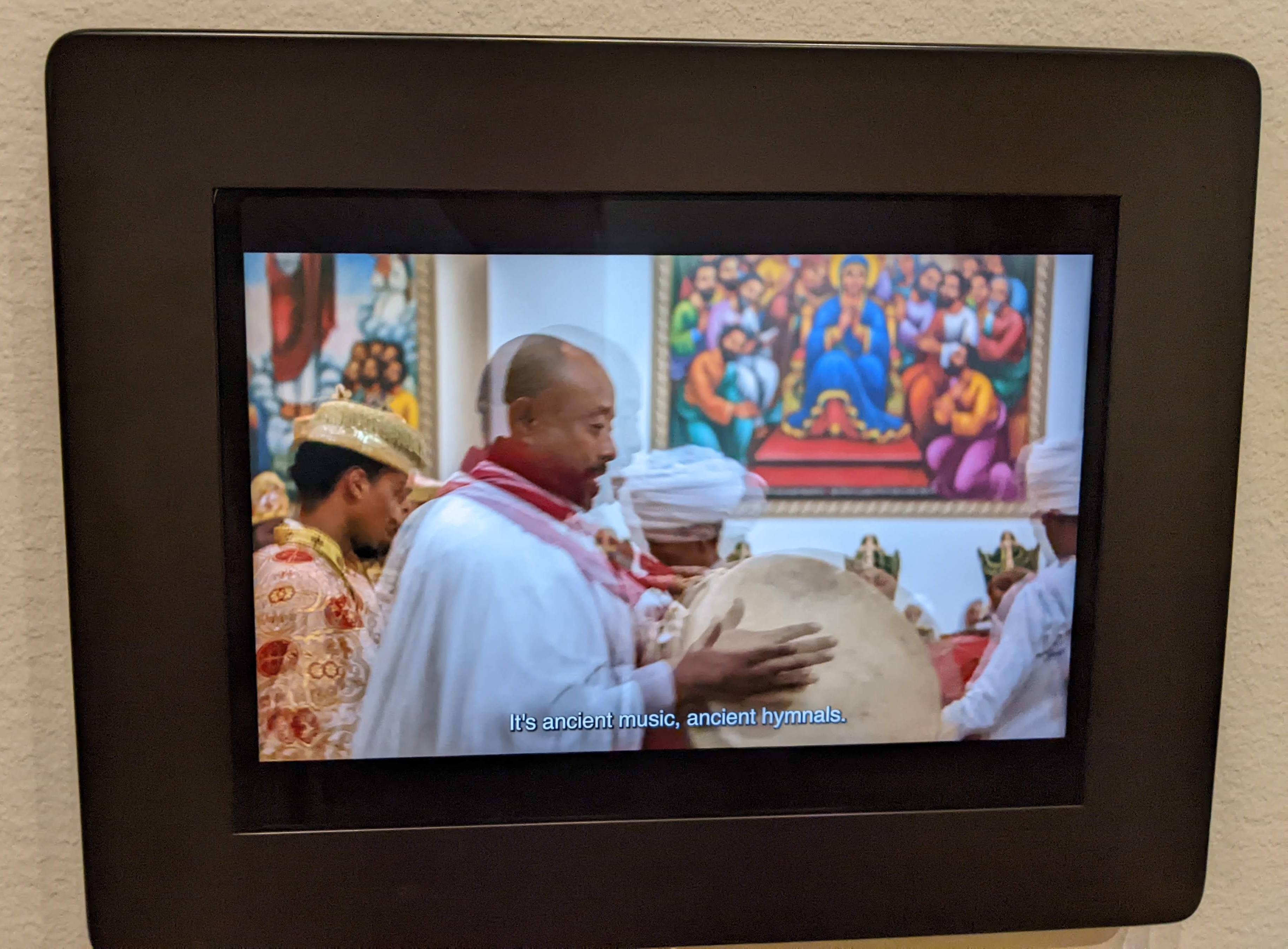

Also in the exhibition there are screens where you can watch videos of Ethiopian Orthodox worship, including music and liturgies, where you will see some of the objects in use. You can also listen to interviews with members of the local Ethiopian diaspora community. (The Washington metropolitan area has the largest Ethiopian population outside Ethiopia.)

Further contextualizing the objects and enhancing the sense of place, pasted onto the wall is a blow-up photograph of a Christian holy-day celebration wending through the streets. This serves as a backdrop to two physical artifacts present in the room: a qämis (dress) and a debab (umbrella).

The inscriptions on many of the Ethiopian icons and manuscript illuminations, which identify the figures and scenes, are in Ge‘ez (aka classical Ethiopic), an ancient South Semitic language that originated over two thousand years ago in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. It’s no longer spoken in daily life, but it is still used as the language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and taught to boys in Sunday school. I really wish I could read it, as it would be a great help in interpreting the Ethiopian images I come across in my studies!

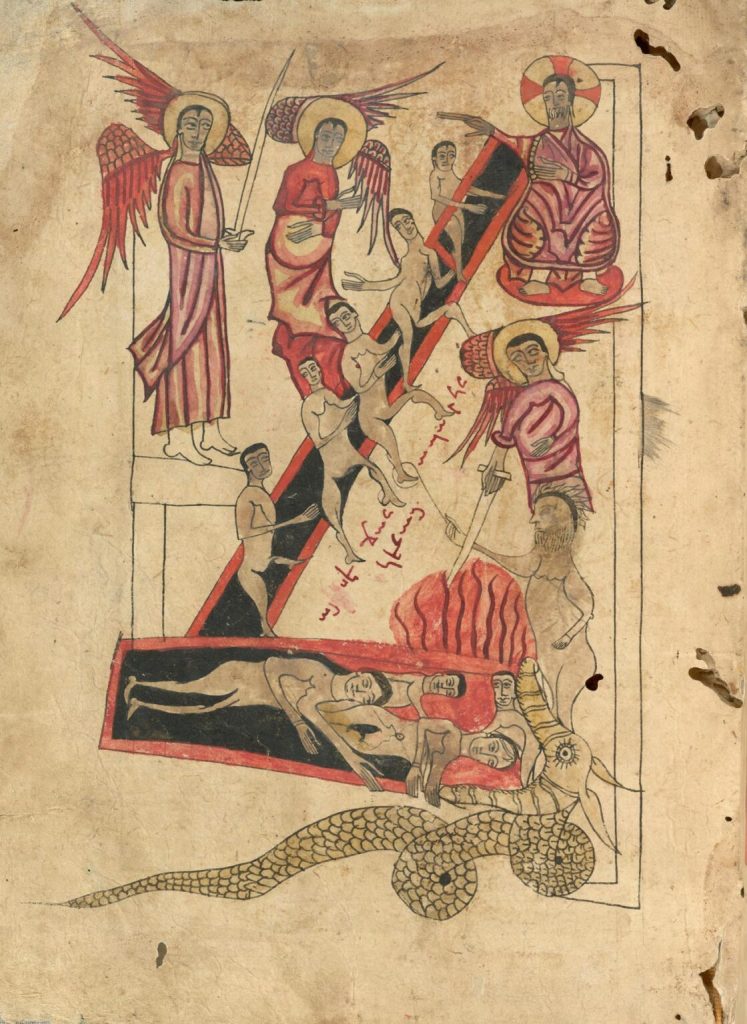

Contrary to what some may assume, Ethiopians in the medieval era were not an isolated people. They traveled—to Rome, to Jerusalem, and so forth. Evidence of Holy Land pilgrimage is suggested by an early fourteenth-century Gospel book that includes the domed Church of the Holy Sepulcher as the backdrop for Christ’s resurrection:

This is an extraordinary book, one of the oldest surviving Ethiopian manuscripts and the oldest in North America. Ethiopian artists weren’t yet depicting Jesus on the cross, so to represent the Crucifixion, this artist has painted a living lamb surmounting a bejeweled cross, with the two thieves crucified on either side.

Also from the fourteenth century, a manuscript opened to a page spread of Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem:

I like how the scene extends across both pages, creating a sense of forward progression, and the two onlookers above the city gate.

One of my favorite objects from the exhibition is a sensul from Gondar depicting ten scenes from the life of Mary. A sensul is an Ethiopian chain manuscript, in this case pocket-size, created out of a single folded strip of parchment attached to heavy hide boards at each end, which creates a small book when folded shut. Here’s a detail showing the Annunciation:

It’s a common misconception that Ethiopians have always depicted biblical figures as dark-skinned to reflect the local population. Such treatment didn’t become normative until the eighteenth century, although some earlier artists did choose black complexions for holy persons:

In the triptych shown above, not only is the infant Jesus depicted as Black, but he also wears a necklace made of cowrie shells, which are traditionally given to Ethiopian children for protection!

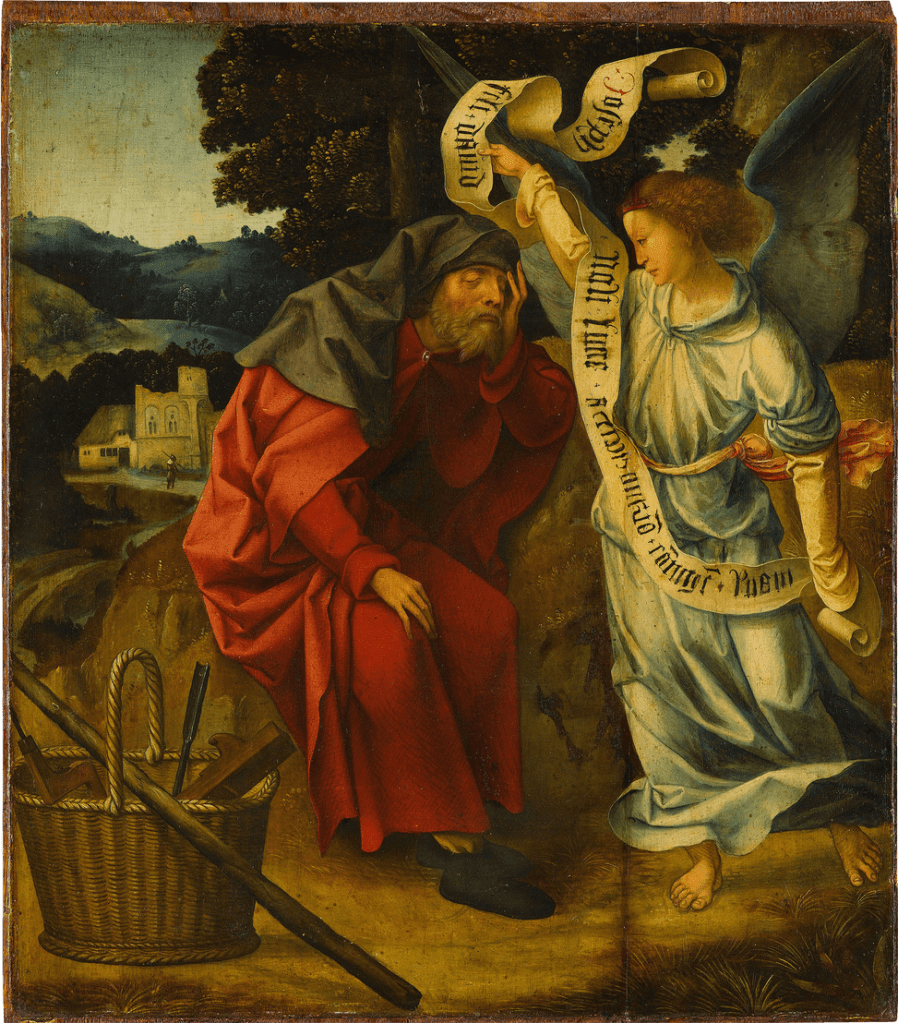

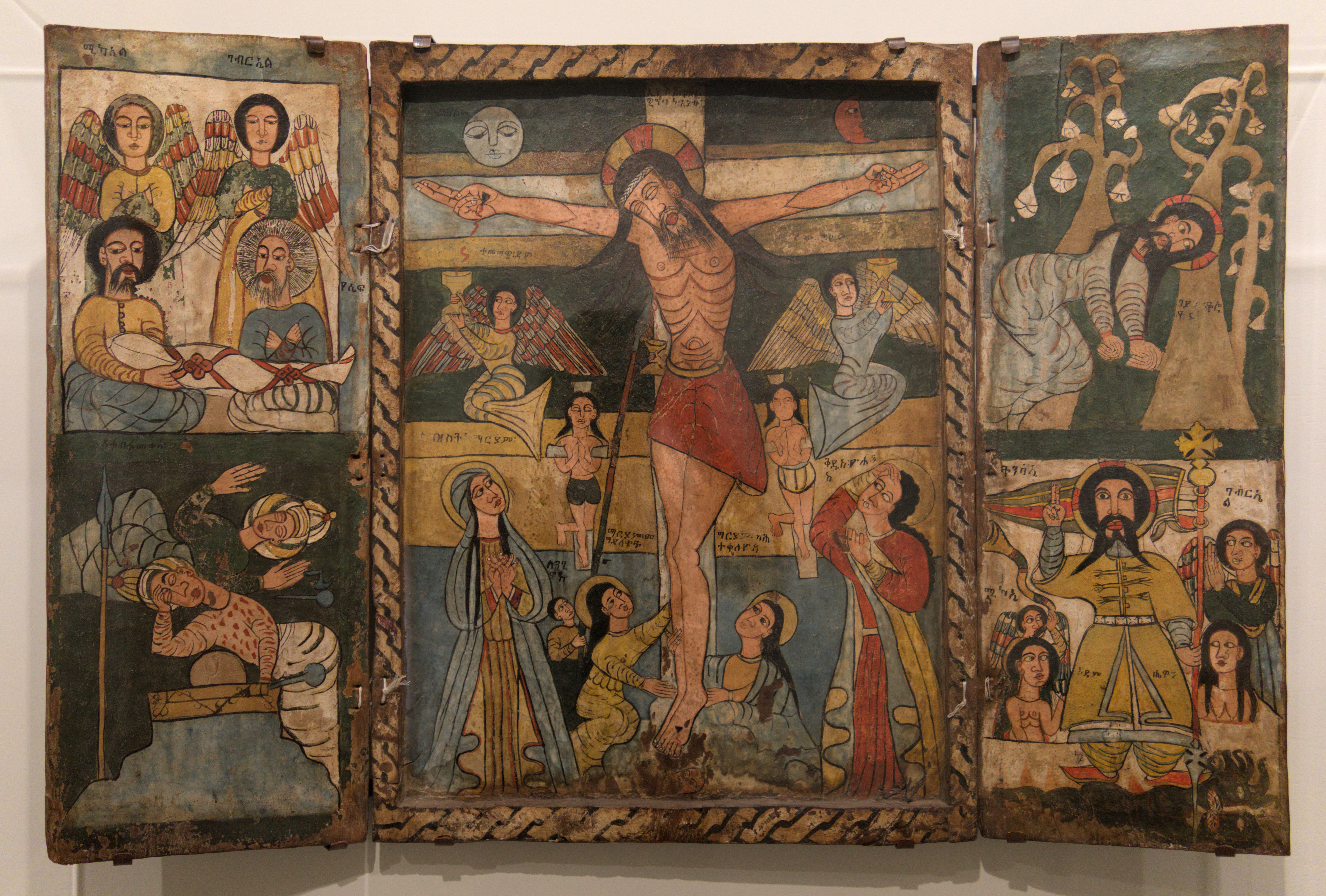

My favorite artwork from the exhibition is probably this triptych:

Its central panel depicts the Crucifixion, Christ’s head bowed in death and his fingers gesturing blessing, even as his palms are nailed. At the top, the sun and the moon mourn his passing. As we saw before, angels catch the blood that drips from his body (notice the cute little hand sticking out from behind his torso!). At the base, the two larger-scale figures are the Virgin Mary and St. John, while next to Mary on a smaller scale is Longinus, the centurion who pierces Christ’s side with a spear.

The left wing shows the Entombment of Christ, with two guards, wearing pointed turbans, sleeping at their post. The right wing shows a scene that the label identifies as “Temptation in the Wilderness” (presumably a translation of the inscription on the tree) but that looks to me more like an Agony in the Garden. Below that is the Resurrection, with Christ holding a victory banner, standing atop Hades. An angel blows a shofar and the dead rise up out of their graves, following Christ, the firstfruits of the resurrection (1 Cor. 15:20–22). Christ wears a short-sleeved, knee-length jacket with frog closures, and bunched sleeves and trousers, both of which reflect clothing from regions east of Africa.

The wall text notes the fine, wavy lines used to render the figures’ draperies, perhaps influenced by Armenian artists from the Lake Van region.

Here’s another Crucifixion, this one painted in what’s called the Second Gondarine style, characterized by smoothly modeled figures, often with darker skin tones, and wide horizontal bands of red, yellow, and green filling the background:

The squiggles behind Christ at the top left may simply be a decorative motif, but to me they look like falling stars, an apocalyptic sign, and as if the sky is weeping.

The right panel of the diptych shows Christ being cruelly fitted with a crown of thorns.

Two other passion images I want to share are a Last Supper wall painting and an Entombment from a disbound album.

In the Last Supper, Jesus and Judas both dip their bread (injera!) into the same bowl and exchange a knowing glance.

In the Entombment, Jesus, wrapped in white linen, is lowered into the ground, mourned by several of his women followers. The portrayal of his mother Mary’s weeping, her hands covering her eyes and her face stained with tears, is particularly poignant. This leaf is from a set of forty-four, now matted separately but originally arranged in series and likely painted on several long sheets of parchment that were sewn together and folded accordion-style to form a sensul.

One of the most extraordinary objects on display is a rare folding processional icon that adopts the form of a fan, from the late fifteenth century:

Thirty-eight identically sized figures span the surface of this elongated parchment: the early Christian martyrs Julitta (Juliet) and Cyricus, St. George, St. John the Baptist, the archangel Michael, the Virgin Mary, the archangel Raphael, St. Paul, the Ethiopian artist-priest Afnin, and unidentified Old Testament patriarchs and prophets. There would have been a wooden handle attached to either end that, when pulled together, created a double handle for a giant wheel to be displayed during liturgical processions and church services (see here). As the museum website notes, “The Virgin Mary, whose hands are raised in a gesture of prayer, is then at the top of the wheel. By depicting Mary in the company of saints and angels, the icon powerfully evokes the celestial community of the church.”

This is just a sampling of all the wonderful art objects that are a part of the Ethiopia at the Crossroads exhibition. I’ll share more photos on Instagram (@art_and_theology) in the coming weeks.

I strongly encourage you to go see this! I think it would be enjoyable for children as well, especially Christian children, who will be able to identify many of the painted stories. For Christians, it’s an opportunity to connect with our artistic heritage and with African church history. If you can’t catch the exhibition at the Walters in Baltimore before it closes March 3, it will be traveling to the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (April 13–July 7, 2024), and the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio (August 17–November 10, 2024).

Also, a catalog is coming out in April, where you will find photos of all the artworks in addition to illuminating essays.