I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. . . . No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at. [1]

What is more far reaching than beauty? [2]

Last October I saw the wonderful retrospective exhibition Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, co-organized by the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, and the Columbus Museum in Columbus, Georgia. Taking its title from the 1970 hit song by Ray Stevens (which was on the mixtape Thomas listened to while she painted), the exhibition shows that Thomas’s creativity extended beyond the studio to encompass interior design, costume design, fashion, puppetry, teaching, service, gardening, and more.

Alma Thomas (1891–1978) was an African American artist best known for her exuberant abstract paintings inspired by the hues, patterns, and movement of trees and flowers in and around her neighborhood in Northwest Washington, DC. Seeking relief from the racial violence in her native Georgia and better educational opportunities, she moved to Washington with her family at age fifteen and remained there for the rest of her life. In 1924 she became Howard University’s first fine arts graduate, and after that taught art for thirty-five years at Shaw Junior High School, leaving behind a celebrated legacy as an educator and a champion for Black youth. She was also an active member of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, through which she founded the Sunday Afternoon Beauty Club, organizing field trips, lectures, and other activities to promote arts appreciation.

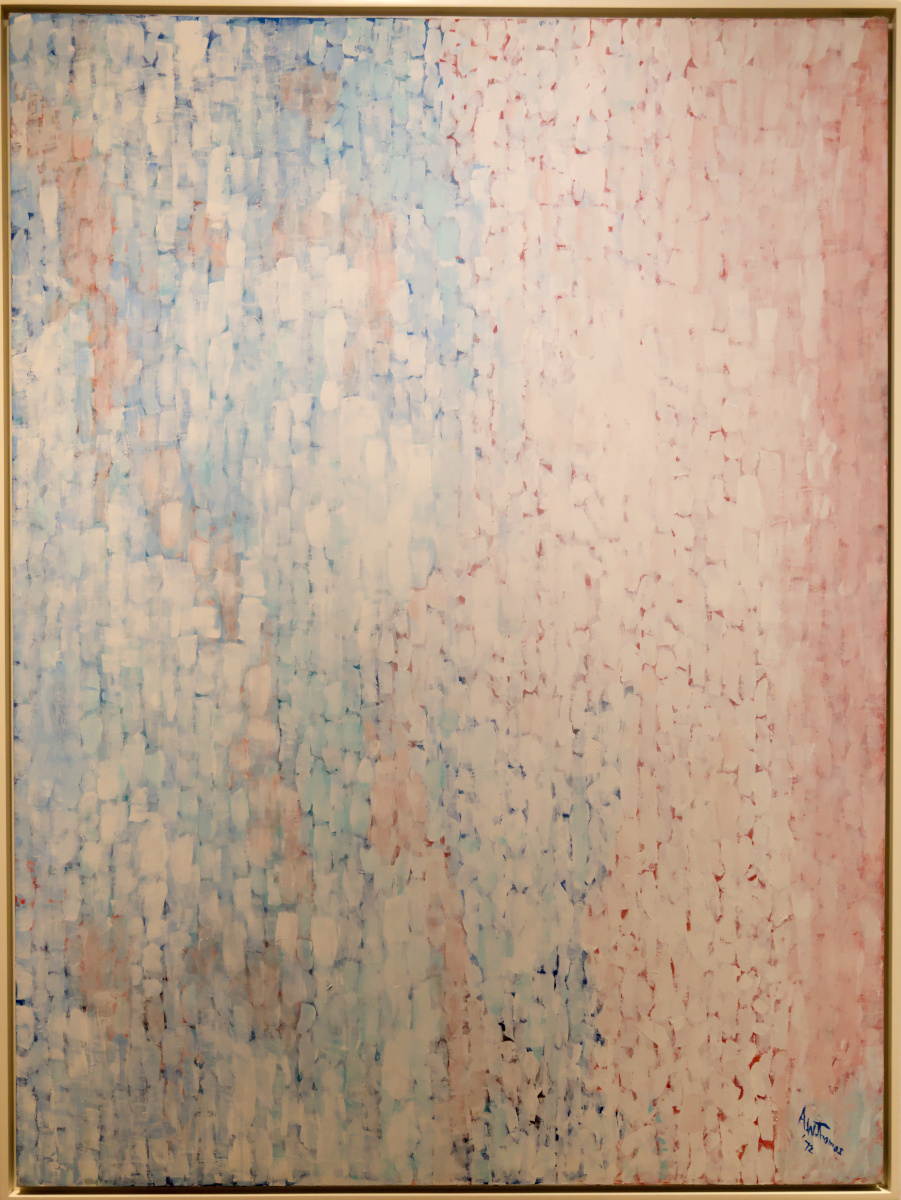

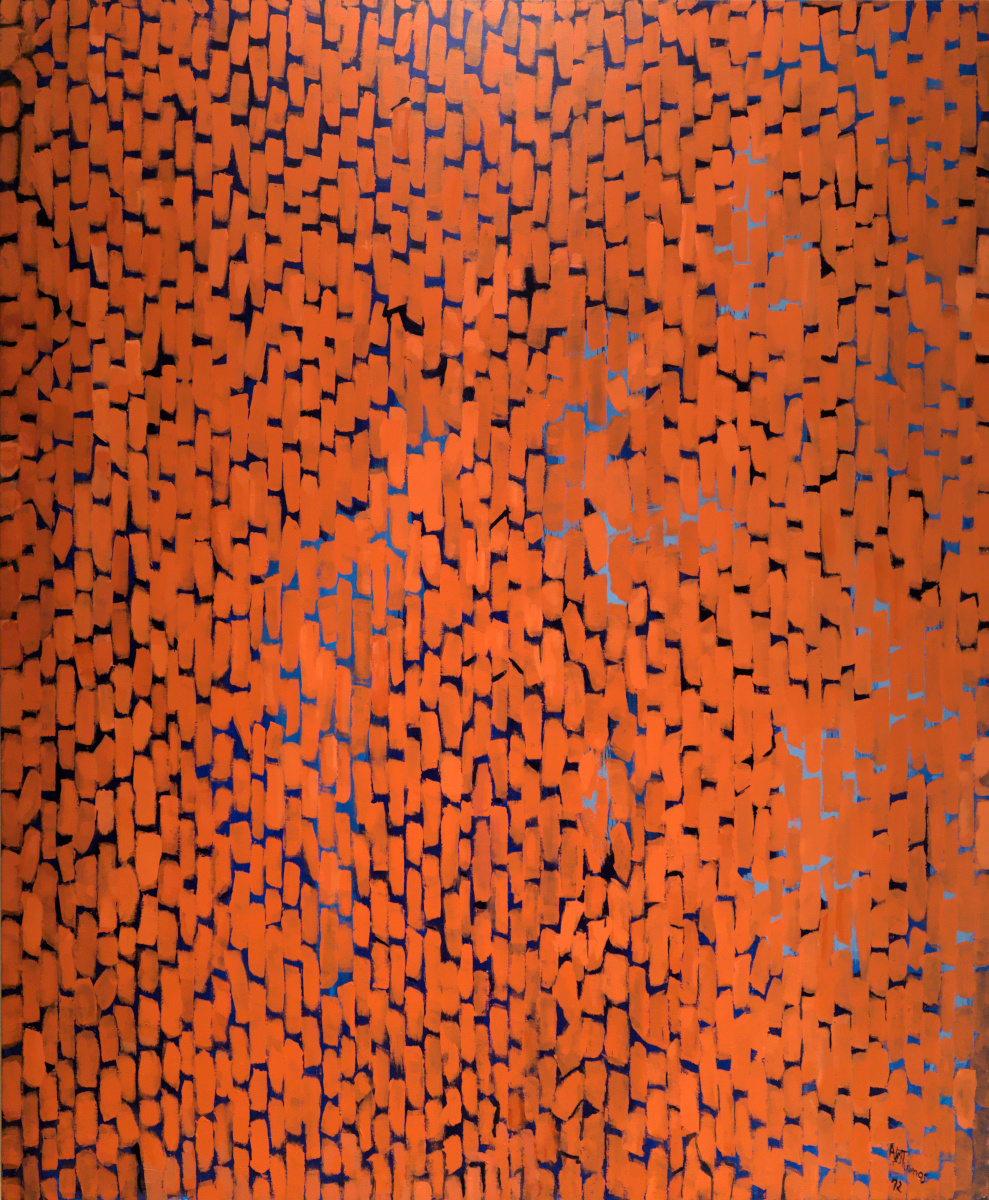

Though Thomas had been painting for decades, she didn’t develop her signature style—consisting of vibrant paint pats arranged in columns or concentric circles—until about 1965, after retiring from teaching; she called these irregular free blocks “Alma’s Stripes.” Her exploration of the power of simplified color and form in luminous, contemplative, nonobjective paintings means she is often classified as a Color Field painter, and she is particularly associated with the Washington Color School. At age eighty she had her first major exhibition, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 1972. She was the first Black woman to receive a solo show at this prestigious museum, and the show won her instant acclaim.

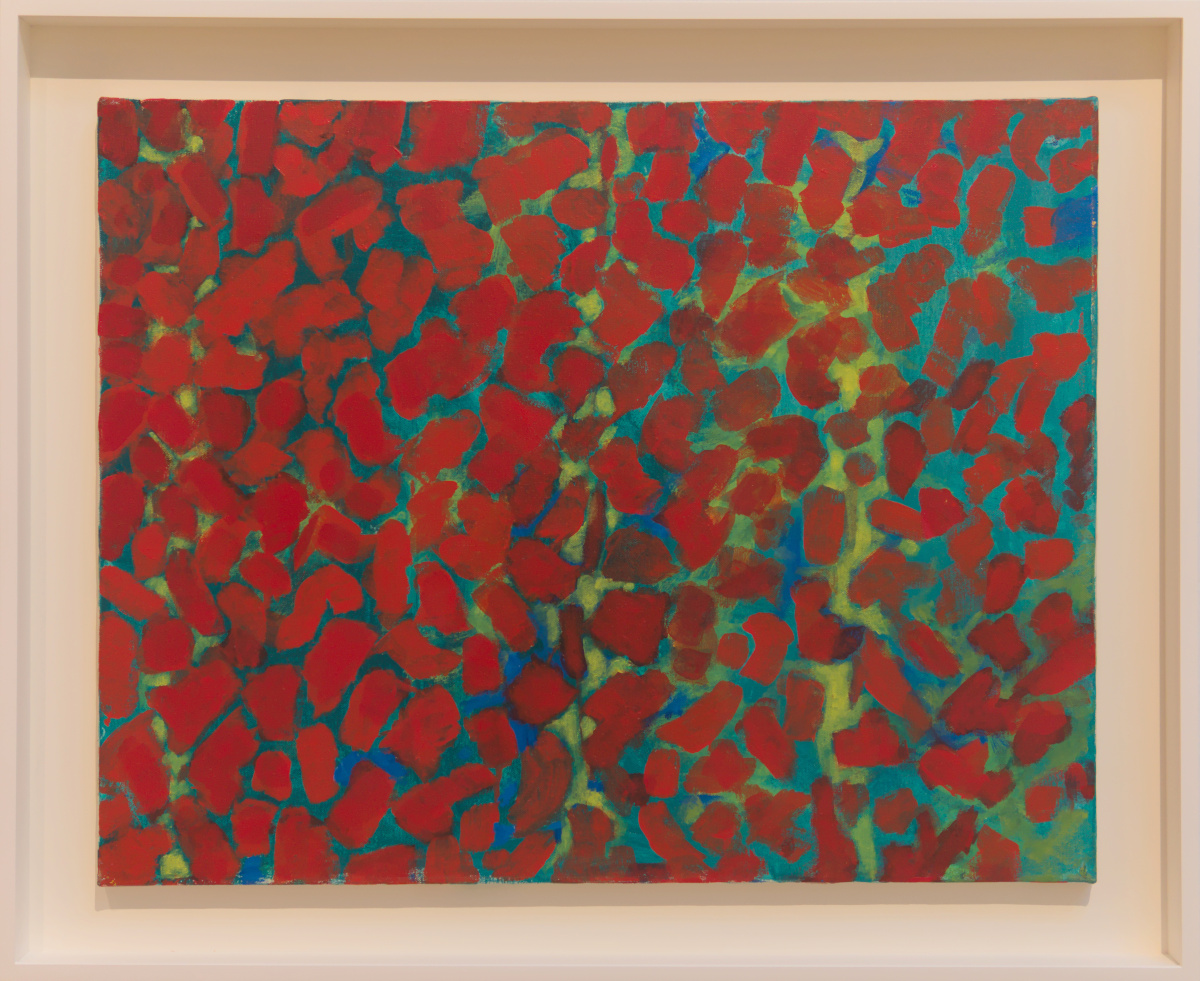

The natural world was an enduring source of inspiration for Thomas. She kept a flower garden in her backyard and frequented the green spaces of the nation’s capital. She described the holly tree visible through the bay window of her living room with great relish:

That tree, I love it. It’s the one who inspired me to do this sort of thing. The composition in the bay window reached me each morning—the colors, the wind who is their creative designer, the sunshine filtering through the leaves to add joy. The white comes through those leaves and gives me the white of the canvas. I’m fascinated by the way the white canvas dots around, and above, and through the color format. My strokes are free and irregular, some close together, others far apart, thus creating interesting patterns of canvas peeking around the strokes. [3]

Thomas saw nature as having a musicality, an idea underscored by many of the titles she gave her paintings, which pair terms from classical music especially—such as “symphony,” “sonata,” “concerto,” “rhapsody,” “étude”—with the names of trees or flowers. Nature sounds forth an array of notes, all in resplendent harmony with one another. And its compositions are new every morning!

(Related post: “Nature as extravagant gift from God”)

Thomas’s rhythmic dabs of prismatic color express joy, celebration, and wonder at God’s creation and are reminiscent of those biblical psalms in which nature is said to praise God (e.g., Psalm 19:1–3; Psalm 65:12–13; Psalm 96:11–12; Psalm 98:4–8). Not only is nature animate; it sings and dances and claps its hands.

Many of Thomas’s paintings, whether of outwardly radiating rings or parallel rows, are meant to suggest an aerial view of flower beds or nurseries. “I began to think about what I would see if I were in an air-plane,” she said. “You streak through the clouds so fast you don’t know whether the flower below is a violet or what. You see only streaks of color.” [4]

Eventually, Thomas’s vocabulary of vertically or circularly organized paint pats expanded to include “wedges, commas, and other glyphic shapes formed entirely by her brush and arranged in tessellated patterns” [5], which have the same vibratile quality. Grassy Melodic Chant visually references the path to her garden, which featured dark flagstones with off-white mortar borders.

At over thirteen feet long, the monumental three-paneled Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music (1976) is Thomas’s most ambitious painting and the touchstone of the exhibition. She painted it two years before her death, when she was suffering from painful arthritis, deteriorating vision, and the lasting repercussions of a broken hip. Though she had to adapt her technique to accommodate these ailments, her aesthetic vision is masterfully executed, and most people regard this as her magnum opus.

In addition to her enthusiasm for local, seasonal flora, Thomas was also really interested in space exploration. Like many Americans, she followed NASA’s lunar and Mars missions on the radio and television. She painted Mars Dust in 1971 as Mariner 9 circled the Red Planet, attempting to map its surface but being held up by a massive dust storm.

She also painted several works inspired by images taken of Earth during the Apollo 10 and 11 spaceflights, such as Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset (not pictured)—Snoopy being the name of the lunar module. Starry Night with Astronauts is the final work in her Space series.

Thomas’s choice to paint apolitical abstractions rather than taking the Black human figure as her subject was somewhat controversial. Members of the Black Arts Movement rigidly insisted that “Black artists should be making work that furthered the goals of Black liberation by speaking directly to their own communities rather than trying to fit into white aesthetic frameworks or addressing non-Black audiences. . . . In the process, they largely rejected visual abstraction because it was rooted in a European modernist tradition, one that had very little to do, they believed, with the lives and urgencies of Black folks.” [6]

Thomas disliked being pigeonholed as a “Black artist” and resisted the idea that responsible art must be oriented toward social activism. “We artists are put on God’s good earth to create,” she said. “Some of us may be black, but that’s not the important thing. The important thing is for us to create, to give form to what we have inside us. We can’t accept any barriers, any limitations of any kind, on what we create or how we do it.” [7] And elsewhere: “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” [8] In finding success as an abstractionist focused on beauty in nature and in technological innovation, she broke down barriers of what were considered (by both whites and Blacks) acceptable styles and subject matter for African American art.

This doesn’t mean Thomas was indifferent to Black progress. On the contrary, she was deeply involved in advancing racial uplift in her own community.

Thomas, far from retreating from the world, had always flung herself headlong into it. She devoted her life to advancing the lives of her Black students, peers, and neighbors—from her commitment to education (“Education is the strongest weapon we [African Americans] have,” she insisted); to her work to establish an art gallery that would collect the creations of Black people so as to begin to build an art historical archive; to her collaborations with civil rights organizations and publications; to her backyard garden, which she treated as a small offering of beauty in the midst of her gritty surroundings. [9]

Her one political painting, for which she painted two preparatory sketches, is on the August 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which she participated in.

She also painted a few explicitly religious subjects, among them the Journey of the Magi and the Entombment of Christ.

Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful has left the Phillips but will be at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville from February 25 to June 5, 2022. From there it will visit the Columbus Museum in Columbus, Georgia (Thomas’s birthplace), from July 1 to September 25, 2022.

At the archived Phillips exhibition page, you can find video lectures and conversations and audio commentaries, plus you can take a 360-degree virtual tour of the exhibition. Washington-area readers: if you missed Everything Is Beautiful and want the chance to see Thomas’s work in person, mark your calendars for October 2023, when the Smithsonian American Art Museum will be exhibiting the more than two dozen Thomas paintings in its collection; the show is called Composing Color: Paintings by Alma Thomas.

There is plenty of material out there about Alma Thomas. A few other resources I’ll point you to are the Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful catalog, of which the following video gives you a look inside:

The National Women’s History Museum also curated an interactive online exhibition about Thomas through Google Arts & Culture.

NOTES

1. Alma Thomas, quoted in Eleanor Munro, Originals: American Women Artists (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979), 194.

2. This rhetorical question of Thomas’s is printed beneath her 1924 senior class photograph in The Bison, Howard University’s annual. Seth Feman and Jonathan Frederick Walz, eds., Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021), 78 (fig. 3).

3. Quoted in Andrea O. Cohen, “Alma Thomas,” DC Gazette, October 26–November 8, 1970.

4. Alma Thomas Papers, untitled statement, Biographical Accounts and Notes, c. 1950s–c . 1970s, box 1, folder 2, page 10.

5. Sydney Nikolaus, et al., “Composing Color: The Materials and Techniques of Alma Woodsey Thomas,” in Feman and Walz, 105.

6. Aruna D’Souza, “What Filters Through the Spaces Between,” in Feman and Walz, 61.

7. Quoted in Adolphus Ealey, “Remembering Alma,” in Merry A. Foresta, A Life in Art: Alma Thomas, 1891–1978 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1981), 12.

8. Quoted in David L. Shirey, “At 77, She’s Made It to the Whitney,” New York Times, May 4, 1972, 52.

9. Aruna D’Souza, “What Filters Through,” 69.