The English Crucifixion lyric “My Fearful Dream” (also known by the beginning of its first line, “To Calvary he bore his cross”) was written anonymously in the fifteenth century. It is preserved, with music by Gilbert Banastir (sometimes spelled Banaster or Banester) (ca. 1445–1487), on folios 77v–82r of the famous Tudor songbook BL Add. MS. 5465, intended for use at the court of King Henry VII. Compiled around the year 1500, this manuscript is commonly referred to as the Fayrfax Manuscript after Robert Fayrfax, the Tudor composer who was organist of St. Albans and a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal—that is, an adult male singer in the monarch’s household choir. It contains twelve sacred songs and thirty-seven secular songs, all in English—with, “beyond question, the finest music written to vernacular words which survives from pre-Reformation England,” writes John Stevens in Early Tudor Songs and Carols (xvi). It is unknown whether the text or the music was written first.

In 1982 “My Fearful Dream” was performed by Pro Cantione Antiqua under the direction of Mark Brown at the Church of St. John-at-Hackney in London. The recording of this performance was originally released in 1985 in vinyl format on A Gentill Jhesu: Music from the Fayrfax Ms. and Henry VIII’s Book (Hyperion A66152) and was later reissued by Regis Records in 2006 on the CD Tears & Lamentations: English Renaissance Polyphony (RRC 1259). Unfortunately, the CD is out of print, the choral group is inactive, and I can find no performances online. I thus provide the recording of “My Fearful Dream” (or “My Fearfull Dreme,” as the track list spells it) directly below for educational purposes. It is a song for three voices: alto, tenor, bass.

Below is the original text as transcribed by Richard Leighton Greene from the Fayrfax Manuscript in The Early English Carols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935), page 124, followed by a version with modernized spellings and updates of a few antiquated words. The text also appears in John Stevens, Music and Poetry in the Early Tudor Court (London: Methuen, 1961), no. 56, and the music in John Stevens, ed., Early Tudor Songs and Carols (Musica Britannica 36) (London: Stainer and Bell, 1975), page 476.

Pro Cantione Antiqua does not sing the third stanza.

Most people today use the word “carol” as synonymous with a cheerful Christmas song. But up until about 1550, the term was used for lyrics of a certain form rather than a certain subject or spirit. Greene defines the medieval or Renaissance carol as “a song on any subject, composed of uniform stanzas and provided with a burden . . . [that is,] an invariable line or group of lines which is to be sung before the first stanza and after all stanzas” (Early English Carols, xxxii–xxxiii). He distinguishes a burden from a refrain: “The refrain, as defined in this essay, is a repeated element which forms part of a stanza, in the carols usually the last line. The burden, on the other hand, is a repeated element which does not form any part of a stanza, but stands wholly outside the individual stanza-pattern” (clx).

That’s why “My Fearful Dream” can properly be called a carol. The two lines beginning “My fearful dream” open the song and repeat after each stanza.

My Feerfull Dreme

My feerfull dreme nevyr forgete can I:

Methought a maydynys childe causless shulde dye.

To Calvery he bare his cross with doulfull payne,

And theruppon straynyd he was in every vayne;

A crowne of thorne as nedill sharpe shyfft in his brayne;

His modir dere tendirly wept and cowde not refrayne.

Myn hart can yerne and mylt

When I sawe hym so spilt,

Alas, for all my gilt,

Tho I wept and sore did complayne

To se the sharpe swerde of sorow smert,

Hough it thirlyd her thoroughoute the hart,

So ripe and endles was her payne.

My feerfull dreme . . .

His grevous deth and her morenyng grevid me sore;

With pale visage tremlyng she strode her child before,

Beholdyng ther his lymmys all to-rent and tore,

That with dispaire for feer and dred I was nere forlore.

For myne offence, she said,

Her Son was so betraide,

With wondis sore araid,

Me unto grace for to restore:

‘Yet thou are unkynd, which sleith myn hert,’

Wherewith she fell downe with paynys so smert;

Unneth on worde cowde she speke more.

My feerfull dreme . . .

Saynt Jhon than said, ‘Feere not, Mary; his paynys all

He willfully doth suffir for love speciall

He hath to man, to make hym fre that now is thrall.’

‘O frend,’ she said, ‘I am sure he is inmortall.’

‘Why than so depe morne ye?’

‘Of moderly pete

I must nedis wofull be,

As a woman terrestriall

Is by nature constraynyd to smert,

And yet verely I know in myn hart

From deth to lyff he aryse shall.’

My feerfull dreme . . .

Unto the cross, handes and feete, nailid he was;

Full boistusly in the mortess he was downe cast;

His vaynys all and synowis to-raff and brast;

The erth quakyd, the son was dark, whos lyght was past,

When he lamentable

Cried, ‘Hely, hely, hely!’

His moder rufully

Wepyng and wrang her handes fast.

Uppon her he cast his dedly loke,

Wherwith soddenly anon I awoke,

And of my dreme was sore agast.

My feerfull dreme . . .

My Fearful Dream (modernized)

My fearful dream never forget can I:

Methought a maiden’s child causeless should die.

To Calvary he bore his cross with doleful pain,

And thereupon strained he was in every vein;

A crown of thorns, sharp as needles, shoved in his brain.

His mother dear tenderly wept and could not refrain.

My heart did yearn and melt

When I saw him so spilt,

Alas, for all my guilt,

And I wept and did sore complain

To see the sharp sword of sorrow smart,

How it pierced her straight through the heart,

So ripe and endless was her pain.

My fearful dream never forget can I:

Methought a maiden’s child causeless should die.

His grievous death and her mourning grieved me sore;

With pale visage, trembling, she strode before her child,

Beholding his limbs all rent and torn,

That with despair for fear and dread I was near forlorn.

For my offense, she said,

Her Son was so betrayed,

With wounds sore arrayed,

Me unto grace for to restore:

“Yet thou art unkind, which slayeth my heart,”

Wherewith she fell down with pains so smart;

Hardly one word could she speak more.

My fearful dream never forget can I:

Methought a maiden’s child causeless should die.

Saint John then said, “Fear not, Mary; all his pains

He willfully suffers for the special love

He has to man, to make him free that’s now in thrall.”

“O friend,” she said, “I am sure he is immortal.”

“Why, then, do you mourn so deeply?”

“Of motherly pity

I needs must woeful be,

As a terrestrial woman

Is by nature constrained to smart,

And yet verily I know in my heart

From death to life he shall arise.”

My fearful dream never forget can I:

Methought a maiden’s child causeless should die.

Unto the cross, hands and feet, he was nailed;

Violently into the mortise he was cast down;

His veins and sinews were all riven apart and burst;

The earth quaked, the sun was dark, whose light was past,

When he, lamenting,

Cried, “Eli, Eli, Eli!”

His mother was ruefully

Weeping and wrung her hands fast.

Upon her he cast his deathly look,

Wherewith suddenly anon I awoke,

And of my dream was sore aghast.

My fearful dream never forget can I:

Methought a maiden’s child causeless should die.

The speaker of this carol has a dream—a nightmare—of Calvary, where he beholds the ignominious death of Jesus and the agonizing grief of Jesus’s mother and realizes that such suffering was undertaken for his sake, to save him from sin and its fatal consequences. The accusation that Mary hurls at the speaker in her hour of torment is biting: “You slay my heart!” My son is dead because of you. It’s such a humanizing passage, this expression of a mother’s anger at a death that didn’t have to be.

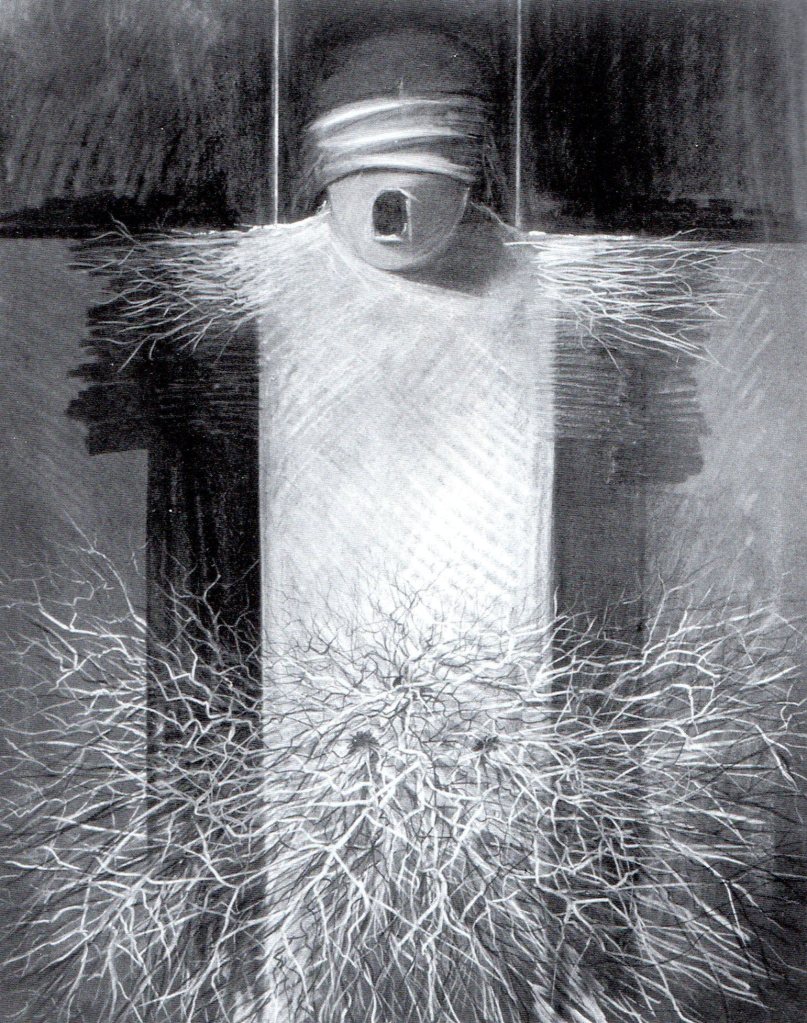

This is the Mater Dolorosa (Latin for “Sorrowful Mother”) of Christian tradition, who is sometimes depicted with a sword (or seven!) in her chest, literalizing Simeon’s prophecy to her as a teen and evoking the piercing sensation of losing a child. In Rogier van der Weyden’s Crucifixion diptych that I’ve reproduced here, created in roughly the same period as “My Fearful Dream” but in the Low Countries, there’s no sword, but Mary’s sorrow is evident in her tear-stained face, the wringing of her hands, and her literally collapsing under the unbearable weight of what she’s been asked to endure.

(Related post: https://artandtheology.org/2023/09/15/her-stations-of-the-cross-by-marjorie-maddox/)

In the carol, the apostle John, present with Mary at the foot of the cross, catches her in her swoon and offers consolation, reassuring her that Jesus suffers willingly out of love. She responds that she knows it in her heart, and that she knows too that he will ultimately rise from death, but that that doesn’t diminish the sharpness of the pain she feels, deep in her body, watching her son shamed and wounded so.

The final image in the dream is of Jesus looking on his mother with a deathly pallor. With that, the speaker is jolted awake and sits with the horror.

On this side of the resurrection, it can be easy to breeze past Good Friday (“He didn’t stay dead!”) or to meditate on the Crucifixion only in a spiritual or theological sense. But this poem, this carol, sticks us in medias res, before the resurrection, into a physical human drama full of emotional intensity, so that we can feel what it might have been like to be present at the execution of the Son of God. Maybe you feel that the graphic details are gratuitous (the thorns shoved in his brain[!], his sinews riven apart, etc.), that sensory engagement with the scene is an exercise that fails to honor the bigger picture, and that it’s fruitless to generate pity for Christ or his mother, as the event is passed and what’s done is done. But centuries of faithful Christians have found otherwise: that meditating on Christ’s pain and that of his mother can help us better appreciate the real-life as opposed to merely mythic dimensions of the story and can cultivate in us a proper horror of sin and a deeper gratitude for Christ’s sacrifice.

The word “causeless” in the burden of the carol—the speaker sees a woman’s child dying without cause—does not imply that Jesus’s death served no purpose, but rather that he was put to death on wrongful charges. The Jewish tribunal charged him with blasphemy for calling himself the Son of God, and the Roman courts charged him with sedition, with inciting insurrection against the empire. But he was telling the truth about his identity and did so in ultimate reverence for God, not lack of it, and while the path he called his followers to would in some ways challenge the values of Rome and reorient ultimate loyalties, he never took up arms or encouraged his followers to do so (quite the contrary), and he never sought political power or overthrow.

Listen once more to Pro Cantione Antiqua’s performance of this carol as it would have been performed for the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, presumably in private religious services for him and his family. May the depths to which God went to save God’s beloved world be something you never can forget.