New Mount Pilgrim commemorates the Maafa, the Great Migration, and martyrs of urban violence and instills hope with trilogy of rose windows, which include an African Christ

Designed by Charles L. Wallace and built in 1910–11, the French Romanesque–style church at 4301 West Washington Boulevard in Chicago’s West Garfield Park neighborhood was originally home to one of the largest Irish Catholic parishes in the city: St. Mel’s (named after Mél of Ardagh, a nephew of St. Patrick from the fifth century). They had the interior decorated with stained glass windows made by the studio of F. X. Zettler in Munich, portraying biblical figures and other saints—all as Caucasian, as was customary at the time and, frankly, still is. St. Mel’s, which merged with Holy Ghost Catholic Church in 1941 (whose parishioners were mainly of German descent), was a flourishing congregation. But in the late 1960s, white people began leaving the neighborhood as Black people moved in, and St. Mel’s membership waned until eventually the church closed its doors in 1988.

After the building had stood vacant for several years, in 1993, the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago sold it to New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, a local Black congregation founded in 1950. The church leaders found that, due to lack of maintenance, the three large rose windows had structural issues that needed to be addressed. Rather than repairing the windows, they decided to replace them with new ones that better reflected the faith stories of their own parishioners—their history, heritage, and aspirations as a community. Rev. Dr. Marshall E. Hatch Sr., who had become the church’s pastor just a month after they moved into the new building and still serves in that role, developed the concepts for the windows with input from the congregation and started fundraising. All three were fabricated by Botti Studio of Architectural Arts in nearby Evanston, Illinois.

The Maafa Remembrance Window

The most striking and theologically profound of the three new windows, and the one I flew to Chicago to see last summer, is the Maafa Remembrance window on the wall to the left of the front altar. Because the church is oriented south rather than the traditional east, this is, directionally speaking, the East Rose Window; it purposefully faces the Atlantic Ocean. It was dedicated December 17, 2000, the church’s fiftieth anniversary year. It replaced an image of the Assumption of Mary (which you can view here); read more about the church building’s original windows on the website of art historian Rolf Achilles.

Maafa (mah-AH-fah) is a Swahili word meaning “great disaster” or “great tragedy.” Since the late 1980s it has been used to refer to the transatlantic slave trade of the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries, during which an estimated 12.5 million African men, women, and children were kidnapped from their homes and forcibly brought to the Americas to work plantations without pay (by and large), building the wealth of their white enslavers. Some scholars prefer the term “African Holocaust” or “Black Holocaust” to describe this historic atrocity.

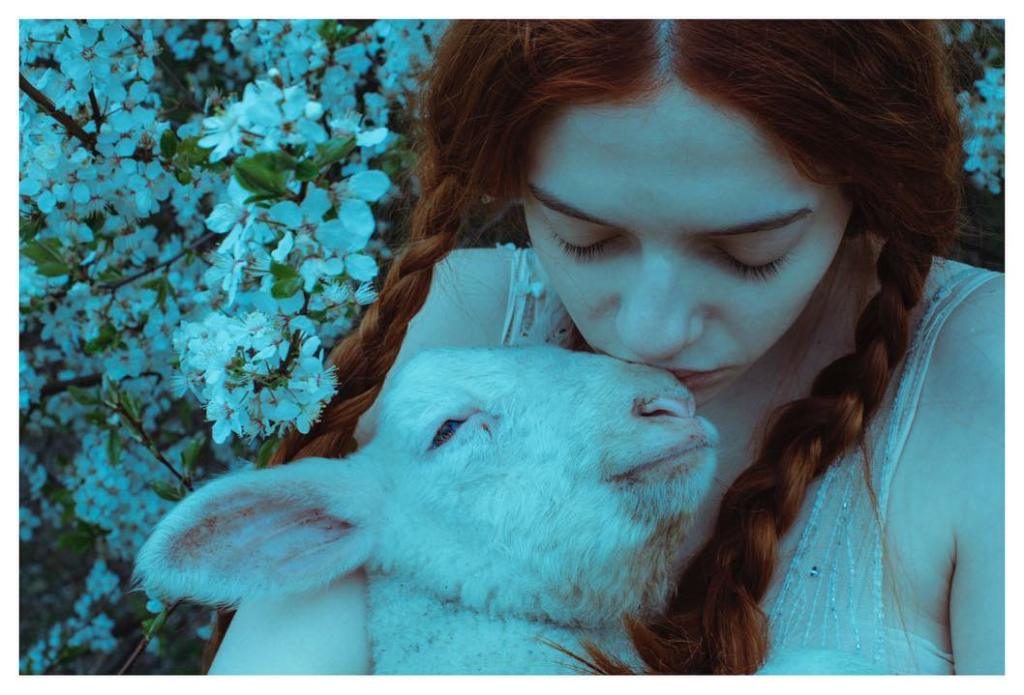

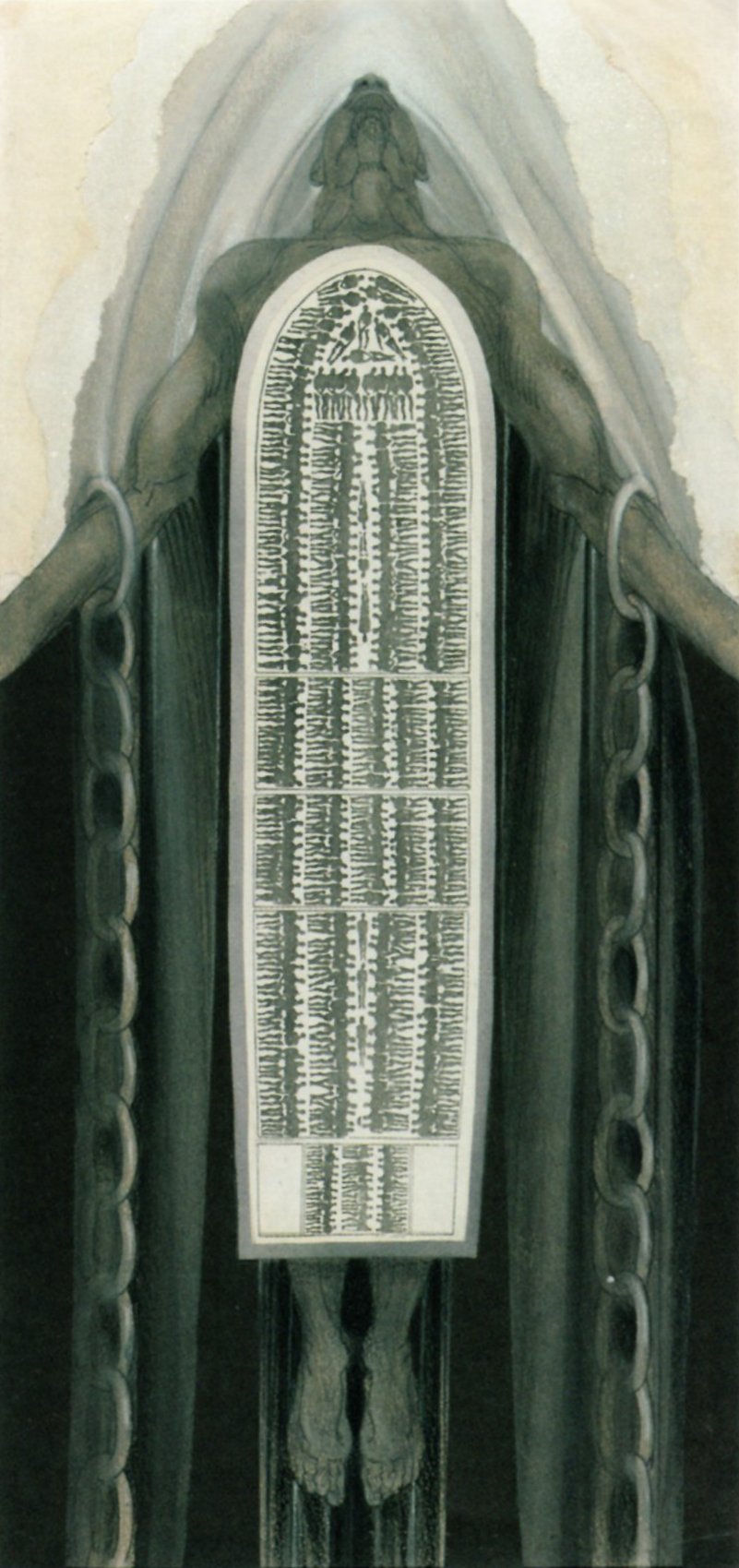

Based on an illustration by Tom Feelings from his extraordinary book The Middle Passage: White Ships / Black Cargo (Dial, 1995), the East Rose Window commemorates the Maafa through an evocation of the Middle Passage, the second leg of the triangular trade route. On this harrowing two- to three-month voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, which ships made many times over chattel slavery’s multicentury duration, at least two million enslaved Africans died of malnutrition, dehydration, disease, captor-inflicted violence, or suicide.

The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers. This wretched situation was again aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

—Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, the African (London, 1789)

In Feelings’s image, an African Christ figure stretches his chained arms out, as if on the cross. His body is constituted by the famous schematic representation of the crowded lower deck of the Brookes slave ship’s human cargo hold, first created in England in 1788 and widely disseminated throughout the nineteenth century. The perspective is such that we’re looking down on a body-as-slave-ship gliding through the waters—but it’s also a crucifixion. The Son of God carries the suffering of the sons and daughters of God, feeling it in his own body. He wears the slave ship like a giant wound that will forever mark him because it has marked his ecclesial body, the church.

The window functions, on one level, as a lament. Consider it in light of the following poem by Lucille Clifton, which draws out the cruel irony of the actual names some ostensibly Christian slave ship owners gave their vessels.

“slaveships” by Lucille Clifton

loaded like spoons

into the belly of Jesus

where we lay for weeks for months

in the sweat and stink

of our own breathing

Jesus

why do you not protect us

chained to the heart of the Angel

where the prayers we never tell

and hot and red

our bloody ankles

Jesus

Angel

can these be men

who vomit us out from ships

called Jesus Angel Grace Of God

onto a heathen country

Jesus

Angel

ever again

can this tongue speak

can these bones walk

Grace Of God

can this sin live

—from The Terrible Stories (1996), compiled in Blessing the Boats: Selected Poems, 1988–2000 and The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton, 1965–2010; © The Estate of Lucille Clifton

The speaker of the poem, an enslaved African, addresses Jesus, questioning why he allows them to be so brutally treated—stolen from their homeland, marched to the coast in chains, claustrophobically packed in ship holds for maximum profitability, and spat out onto auction blocks in a barbarous country that appears to practice the devil’s ways more than God’s. How can God abide such sin? What kind of grace is it that transports them into oppression?

Christian Wiman brilliantly unpacks this poem, noting Clifton’s cunningly subtle tweak of a prophetic passage from Ezekiel that promises resurrection, both of individuals and of a nation. Underneath its acerbity, there’s a certain hopefulness to the poem—a hope that this sin will die, this suffering be transformed. In both Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of dry bones and Clifton’s poem, Wiman writes,

the Word comes streaming again through, and by means of, the word. In terms of the poem, Jesus (the man) is on board Jesus (the ship), but he is in the hold, just as, when the worship services took place above the captured slaves on the Gold Coast of Africa, God, if he was anywhere, was underneath it all, shackled and sweating and merged with human terror.

Emmanuel, God-with-us.

Clinging to this truth, the psalmist declares, “If I make my bed in hell, behold, thou [God] art there” (Psalm 139:8b). In his great compassion, God descends with us into the depths, and bears us up.

The Maafa Remembrance window plays with the themes of descent and ascent. As Emmanuel, Jesus was below deck, in the miserable belly of the thousands of slave ships that traversed the Atlantic, suffering with those chained inside. Christ’s arms are draped with chains, notes Marshall Hatch Jr., the pastor’s son and cofounder and executive director of the MAAFA Redemption Project (more on that below), “but he’s rising. And at some point those chains will break. That’s the hopefulness that shines through.”

Thus, the window commemorates both tragedy and triumph. It honors those who died on the Middle Passage and through the institution of slavery more broadly while also honoring those who persevered all the way to freedom. Hatch Jr. says this Christ is “carrying within himself the memories of those who lost their lives on the journey to America. But also he’s carrying the legacy of those who survived. And we are that living legacy,” descendants of the Middle Passage.

The border around the window’s central image calls parishioners to “REMEMBRANCE.” They must remember their history, the Great Catastrophe their ancestors endured, and, having faced the truth, commit to ending slavery’s legacy of racism in America’s civic, social, and religious spheres and in their own psyches.

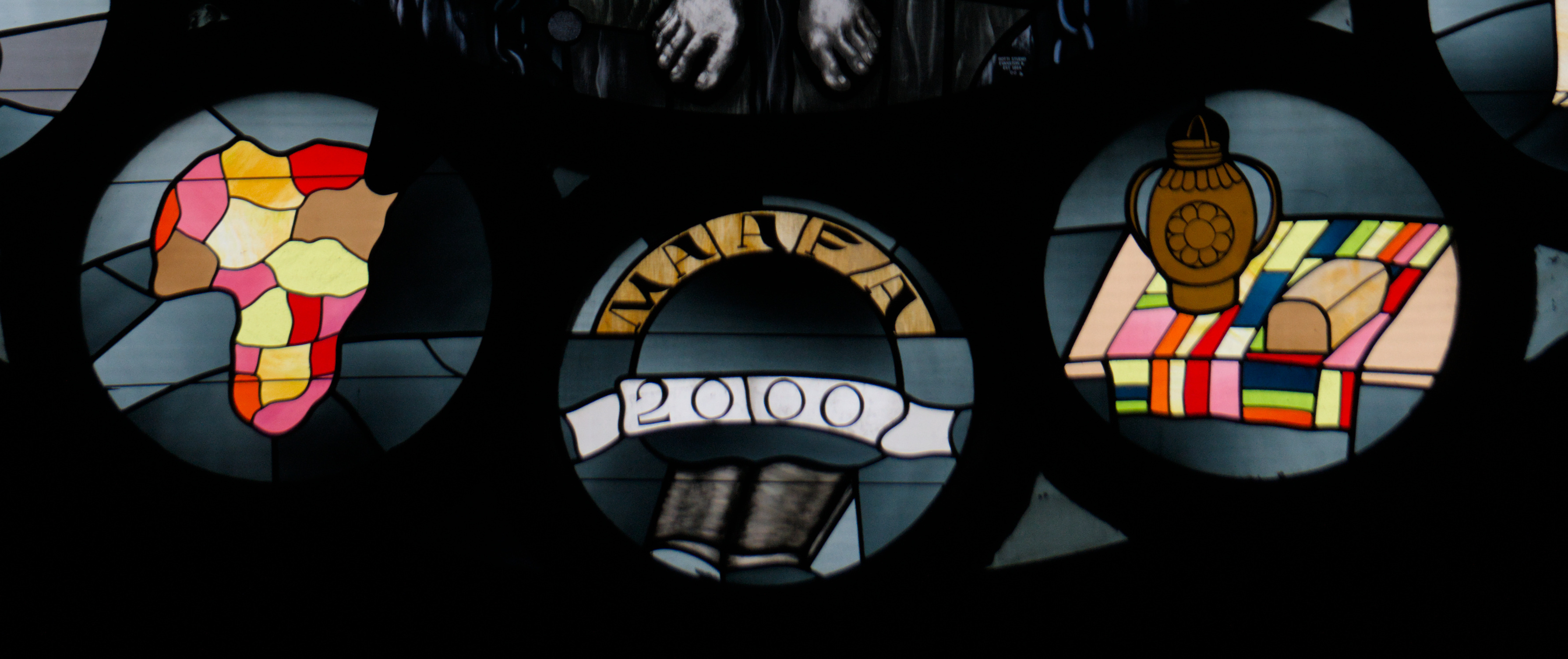

Two of the roundels in the bottom border show a map of Africa and a Communion table laid with kente cloth, a loaf of bread, and a flask of wine. The roundel between these two displays the open word of God, which guides Christians forward in our work of justice and reconciliation.

Art historian Cheryl Finley features New Mount Pilgrim’s Maafa Remembrance window in her book Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon (Princeton University Press, 2022), which traces the origins of the Brookes schematic and its proliferation in mass culture and art. She identifies the window, twenty-five feet in diameter, as the largest example of the “slave ship icon” in the world and writes that, like the cross of Christ, the slave ship embodies both death and rebirth. It is “a site of death, of dying Africans, and of new life, of a people who would persevere in the face of slavery and unspeakable cruelty to become a free people who helped define the modern era” (6).

“The children will need to know that this symbol, this window, is a representation of not only the pain but also the possibilities of a great and mighty God,” Rev. Dr. Gregory Thomas told the Chicago Tribune in 2000. Thomas was a theology professor at Harvard Divinity School, where Hatch Sr. served a fellowship sabbatical semester in 1999 and first encountered Feelings’s Middle Passage book.

In the window, slavery is interpreted in light of the paradox of the cross. Theologian James H. Cone famously interpreted another, later icon of Black suffering—the lynching tree—in light of the same in his essential book The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Orbis, 2011). He opens the book by explaining why and how the cross has held such power for the Black church:

The cross is a paradoxical religious symbol because it inverts the world’s value system with the news that hope comes by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word, that the last shall be first and the first last.

That God could “make a way out of no way” in Jesus’ cross was truly absurd to the intellect, yet profoundly real in the soul of black folk. Enslaved blacks who first heard the gospel message seized on the power of the cross. Christ crucified manifested God’s loving and liberating presence in the contradictions of black life—that transcendent presence in the lives of black Christians that empowered them to believe that ultimately, in God’s eschatological future, they would not be defeated by the “troubles of this world,” no matter how great and painful their suffering. Believing this paradox, this absurd claim of faith, was only possible through God’s “amazing grace” and the gift of faith, grounded in humility and repentance. There was no place for the proud and the mighty, for people who think that God called them to rule over others. The cross was God’s critique of power—white power—with powerless love, snatching victory out of defeat. (2)

A powerful reclamation of Christian iconography, New Mount Pilgrim’s Maafa Remembrance window weds Black history and Christian theology to offer its predominantly African American congregation a communal symbol that honors what they’ve been through as a people and reminds them that they worship a risen Christ who breaks chains and brings life out of death.

The North Star / Great Migration Window

The East Rose Window covered in the previous section is narratively the first in the trilogy of newly commissioned windows, but the first of the three to be fabricated and installed, earlier in 2000, was the North Rose Window, called the North Star or Great Migration window. It commemorates those who traveled north on the Underground Railroad to escape slavery, and, a few generations later (from about 1910 to 1970), as part of a mass movement to escape Jim Crow oppression.

The North Star window shows a Black family unit, the father, in purple robe, lifting his newborn up to the heavens in a gesture of gratitude and pride. The child is backlit by the North Star, a beacon to freedom. The scene recalls the famous naming ceremony in the 1977 Roots miniseries, based on the best-selling novel by Alex Haley, in which Omoro Kinte, a Mandinka man living in The Gambia, carries his firstborn son, Kunta Kinte, to the edge of the village, raises him into the starry night sky, and exclaims, “Behold, the only thing greater than yourself!” This declaration affirms the child’s inherent worth and directs him toward worship of his Creator God.

Later in the story, when Kunta has his first child, Kizzy, thousands of miles away in America, he enacts the same ritual with her.

During New Mount Pilgrim’s baby dedication ceremonies, the pastor raises the child in like manner while the parents vow to bring up the child in the nurture and admonition of the Lord and the congregation vows to support them in this task. This physical gesture of lifting up signifies surrender to God and hope that the next generation will carry the flame of faith out into the city of Chicago and the wider world. Because the North Star window is situated across from the pulpit, over the choir loft and organ, it is in full view of the dedicants.

The inscription below the family in the window reads, “Lift holy hands,” a phrase taken from 1 Timothy 2:8, and the roundels in the border spell out the name of the church. The three portraits at the bottom are of the church’s longest-serving pastors: (from right to left) Rev. J. H. Johnson, the church’s first elected pastor; Rev. James R. McCoy, who served from 1965 to 1993; and Rev. Dr. Marshall Hatch Sr., who has served since 1993. Hatch Sr.’s father and McCoy both participated in the Great Migration, having moved to Chicago from Aberdeen, Mississippi, and so did the majority of the church’s founding members.

The North Star window fills the space previously occupied by a window depicting Saint Cecilia, a Roman virgin martyr.

The Sankofa Peace Window

The West Rose Window, known as the Sankofa Peace window, was the final one to be installed, replacing the clear panes that were there for over two decades. (New Mount Pilgrim sold the original window depicting Mary and the Christ child blessing and accepting the rosary from a male and female saint, to raise funds for the new one.) The Sankofa Peace window was dedicated on February 24, 2019 (watch the service here and view photos here), the year that marked the four hundredth anniversary of race-based slavery in America.

Sankofa is a Twi word from the Akan people of Ghana that means “go back and retrieve it,” a phrase that encourages learning from the past to inform the future. It comes from the proverb “Se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenkyiri”—“It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten,” to return to one’s roots to reclaim lost identity. The concept of Sankofa is traditionally symbolized by a mythical bird with its head turned backward while its feet face forward, carrying a precious egg in its mouth, which represents the knowledge of the past on which wisdom is based.

The Sankofa bird appears in the top center roundel of the window.

Hatch Jr., who preached at the window’s dedication service, discussed Sankofa as a spiritual discipline, highlighting how it can refer not only to returning to one’s cultural roots, but also to God, our Source. “Sankofa is the process of training my soul to reach back and remember the grace and the glory of God,” he says, which can fuel us for the forward journey. He quotes the famous gospel hymn that says, “My soul looks back in wonder how I got over.” We must regale one another with stories of where we’ve been and how far God has brought us, and remind ourselves and each other where we’re heading.

Besides the Sankofa bird, the other four adinkra symbols that New Mount Pilgrim chose to include in the window’s border are:

- Left top: Fawohodie, “Emancipation”

- Left bottom: Gye Nyame, “Omnipotence of God”

- Right top: Odo Nnyew Fie Kwan, “Love Will Lead You Home”

- Right bottom: Mpatapo, “Peace, Reconciliation”

These are key guiding principles of the church, part of their missional purpose and identity. They seek liberation and peace for all, through the power of God, following the path of the Savior who is Love, who brings us back to who we most truly are.

One way the Sankofa Peace window looks backward while moving forward is through the memorialization of murdered Black American youth, from the civil-rights-era South and twenty-first-century Chicago. The portraits at the top depict the four girls who were killed by the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963: Carole Robertson (age fourteen), Addie Mae Collins (fourteen), Denise McNair (fourteen), and Cynthia Wesley (eleven).

The five teens at the bottom, selected by members of New Mount Pilgrim’s youth leadership committee, were victims of Chicago violence from the previous decade or so. From left to right, they are:

- Derrion Albert (1994–2009), age sixteen. On his way home from school, he got caught in the middle of a brawl between two rival factions of students and was beaten to death with a railroad tie. The crime was captured on cellphone video.

- Laquan McDonald (1997–2014), age seventeen. He was shot sixteen times by a police officer while he was walking away.

- Hadiya Pendleton (1997–2013), age fifteen. She was killed by a stray bullet while hanging out in a park with friends after her final honors exams.

- Blair “Bizzy” Holt (1990–2007), age sixteen. He was fatally shot on a CTA bus while shielding his friend from gang gunfire.

- Demetrius “Nunnie” Griffin Jr. (2000–2016), age fifteen. A lifelong member of New Mount Pilgrim, he was burned to death in a trash can in a West Side alley. His death was ruled a homicide, but his killer(s) have not been found. He had told his mother that a gang had been trying to recruit him.

All nine children are dressed in traditional African headwear.

Even as the window laments these unjust deaths, it also provides a vision of restoration. The central scene shows Jesus as the Good Shepherd, leading his children to green pastures and still waters lined with thatched-roof homes—an Edenic place of peace and rest. One might view this as the afterlife (Hatch Sr. told me the children are “going back to the Father’s estate”); but it could also be seen as a picture of Christ leading us into a future on this side of the parousia, where all God’s children are safe and thrive on earth as it is in heaven.

Hatch Sr. told me the window is about recovering a village mentality right in the heart of the city, embracing values like hospitality, family, mutual support, elder respect, and the protection and uplift of children. Whereas the North Star window visualizes the literal lifting up of a child, the Sankofa Peace window calls parishioners to do it metaphorically, through the building of strong community and advocacy for policies that prevent violence and tragedy.

The MAAFA Redemption Project

As a tangible outworking of the communal values expressed in its three rose windows, in 2017 New Mount Pilgrim established a workforce, social, and spiritual development program for young Black men in West Garfield Park, which is still running strong. (It graduated its seventh cohort last month!) Called the MAAFA Redemption Project, it is predicated on the belief that redemption and transformation must begin with the individual, and then that personal transformation can effect family and community transformation. The program emphasizes the importance of, as its website says, “remembering the past in order to create a more just and verdant present and future.”

Using a dual direct-service and community-building approach, the program provides housing, job training, educational opportunities, psychotherapy, counseling, and wrapround social services to the young men who enroll. These supports are supplemented with programming that focuses on the arts, cultural identity development, spiritual enrichment, transformative travel, civic empowerment, and life coaching and mentoring.

The square-mile neighborhood of West Garfield Park has the highest rate of gun violence in Chicago and is one of the most crime-dense populations in the nation. The MAAFA Redemption Project seeks to recruit men between the ages of eighteen and thirty who are a part of this gun culture or at risk of becoming so, recognizing that young people are a neighborhood’s greatest resource for change. The project affirms the dignity and promise of the neighborhood’s Black and Brown youth and aims to instill hope in them, empowering them in activism against gun violence and the conditions that create it.

“The young people who come to us are tired of the subculture that only produces death, despair, and falling into the trap of the criminal justice system,” says Marshall Hatch Jr., the cofounder and executive director of the MAAFA Redemption Project. “They want something different for themselves and their loved ones.”

He continues, “We want to create the space for young men to see themselves differently, to reimagine themselves as men and leaders, pillars of this neighborhood. And so our goal is to embrace the truths that they give us of their experience but also challenge them to overcome, just as their ancestors overcame; to develop the inner resources to persevere and to challenge the system so that their sons, their daughters, don’t have to fight the same fights.”

The video storytelling unit NBC Left Field ran a wonderful segment in November 2018 that features the work of MAAFA Redemption Project:

I also recommend the feature-length documentary All These Sons (2021), directed by the Oscar-nominated Bing Liu and Joshua Altman (Minding the Gap) and streaming for free on Tubi, Amazon, and other services. MAAFA Redemption Project is one of the two Chicago antiviolence programs profiled, the other being the South Side’s Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) run by Billy Moore.

Most recently, MAAFA Redemption Project has partnered with other groups to build and share ownership of the Sankofa Wellness Village, a series of interconnected capital projects and social enterprises sited along the Madison and Pulaski corridor in West Garfield Park. Winner of the Chicago Prize awarded by the Pritzker Traubert Foundation, the village will be a sprawling, $50 million campus that will bring critical health, financial, and recreational resources back into the disinvested neighborhood, including a wellness center, a credit union, an art center, a business incubator and entrepreneurial support center, and pop-up fresh food markets.

The Sankofa Wellness Village breaks ground later this summer and is expected to open in late 2025.

Having identified the arts as an unmet need and desire of West Garfield Park residents, MAAFA Redemption Project has taken the reins on what will be called the MAAFA Center for Arts and Activism. They are working to restore the old St. Barnabas Episcopal Church to provide a space where residents can engage in intergenerational art making, relationship building, community organizing, political education, and civic empowerment.

“We’re part of a continuum of that liberation narrative of God,” Hatch Sr. says, referring to his church’s commitment to see their neighborhood flourish.

For another, well-reported article on the New Mount Pilgrim windows that includes many great photographs of them within the larger sanctuary and worship service context, see the Faith & Leadership article “Proclaiming the liberation narrative of God through church art” by Celeste Kennel-Shank.

Conclusion

When in the nineties they inherited a grand church full of Eurocentric stained glass and other decoration from the Irish Catholic community that worshipped there previously, New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church had some decisions to make. How would they honor the history of that sacred space while also making room for their own histories? What adjustments would have to be made to accommodate their different ecclesial and theological tradition? They made a few changes to the sanctuary, but they left most of it intact. The most significant change is the three new rose windows they commissioned to replace the old ones that were buckling. Once the first two were installed, Pastor Marshall Hatch Sr. told me, the space really started to feel like home.

Hatch Sr. spoke to me about “the power of art to reclaim an identity” for youth involved in or susceptible to gang violence. For sure, many local youth have been inspired by the Maafa Remembrance image in particular, which MAAFA Redemption Project uses as its logo, and thus it’s been widely visible throughout the neighborhood. And yet while the “under thirty” demographic is a particular focus of the church’s outreach efforts, the identity-forming power of art holds true for folks of any age. When a West Garfield Park resident enters the New Mount Pilgrim sanctuary for whatever reason—prayer, worship, respite, connection, religious education, compulsion from a family member—they can hopefully see themselves reflected in the imagery of the rose windows, and, in conjunction with the church’s music and preaching ministries, experience healing and revival.

Their culture, their history, their stories are sacralized in stained glass and integrated into the larger story of redemption God is telling.

Perhaps, from viewing the windows, they feel a deep identification with Christ in his crucifixion, or a sense of God’s presence with them in their suffering; perhaps they are dazzled by the dignity and endurance of their ancestors, or are compelled by the freedom Christ offers; perhaps that was one of their friends whose face shines down from the wall, or the niece or nephew of a friend, and they are turned toward somber remembrance of the lost life and moved to concrete action to reduce the city’s violence; perhaps they’re emboldened by the reminder that Christ goes with them as they seek transformation, as they bring to bear the gospel in this present age, in their own lives and the life of their community.

Visit the Church

Address:

New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church

4301 W. Washington Blvd.

Chicago, IL 60624

(To see the windows in the sanctuary, I made a weekday appointment ahead of time with office manager Rochelle Sykes by calling the church at 773-287-5051. She let me in through the side door.)

Closest CTA train stop:

Pulaski (Green Line) (twelve-minute walk)

Worship service:

Sundays, 10:00 a.m.

Further Reading

The Middle Passage: White Ships / Black Cargo by Tom Feelings (Dial, 1995). This is an important work that every American should own a copy of. It consists of fifty-four powerful grayscale drawings that tell the story of the transatlantic slave trade’s Middle Passage. There’s no written narrative, but there is a brief introduction by the historian John Henrik Clarke. The book caught the attention of Marshall Hatch Sr. while he was a scholar-in-residence at Harvard Divinity School in 1999 and led him to reach out to Feelings for permission to have a stained glass window made based on one of the illustrations.

Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon by Cheryl Finley (Princeton University Press, 2022). Thank you to Marshall Hatch Sr. for recommending this book to me. Finley, an art historian, explores how an eighteenth-century engraving of a slave ship became a cultural icon of Black resistance, identity, and remembrance, its radical potential rediscovered in the twentieth century by Black artists, activists, writers, filmmakers, and curators who have used it as a medium to reassert their common identity and memorialize their ancestors. It’s heavily illustrated and an insightful read, academic in tone but very accessible.

Painting the Gospel: Black Public Art and Religion in Chicago by Kymberly N. Pinder (University of Illinois Press, 2016). This is where I first found out about the Maafa Remembrance window at New Mount Pilgrim. It’s one of sixty-some Black-affirming religious images from Chicago churches and their neighborhoods made between 1904 and 2015 that Pinder, an art historian, features, focusing on their intersection with the social, political, and theological climates of the times. Read my review here.

“Voices from Chicago’s Most Violent Neighborhood” by Andy Grimm, Chicago Sun-Times, 2023. The Sun-Times spent months last year talking to residents of West Garfield Park about why they’ve chosen to stay despite the rampant violence, and they’ve presented some of these stories in a well-designed, interactive web feature. One of the remarks that stands out to me is: “The most dangerous residents of the neighborhood are also the most endangered.”