This roundup is a bit longer than usual, but I’ve found that these six items I’ve gathered over the last month complement each other well, so I’m sharing them all at once. The Art in America and Hyperallergic articles raise interesting points about sacred art—what it is, how it functions, what its relevance is to contemporary life—and this is a topic I discuss in a podcast episode that was released earlier this month. Tammy Nguyen and Wes Campbell are two artists whose work I am glad to have just learned about and plan to explore more of. And there’s always something going on in London’s art scene to remark on as relates to theology or Christian history—this time a National Gallery–sponsored virtual exhibition on the fruits of the spirit, and the latest winning entry for the Fourth Plinth competition, which honors a Baptist pastor and freedom fighter from Malawi.

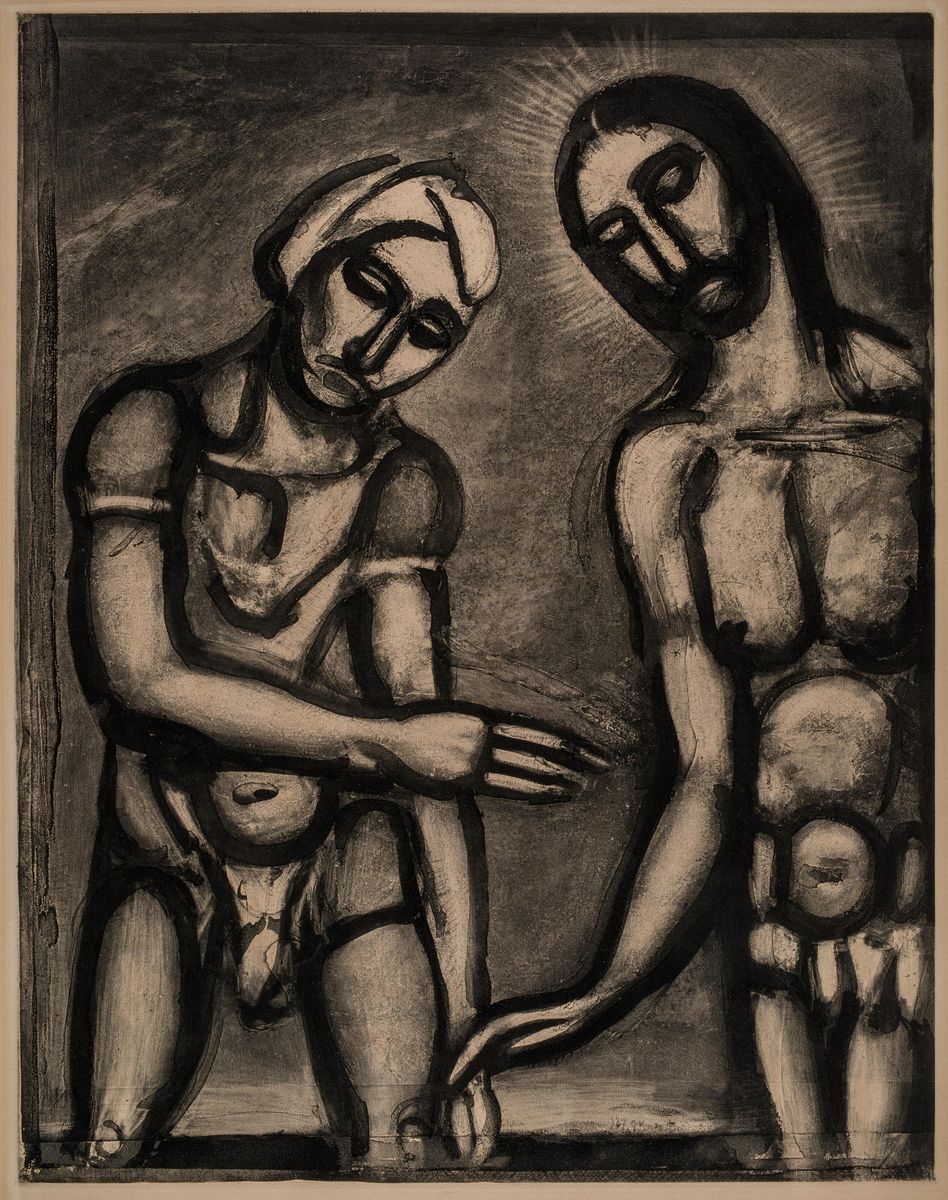

ARTICLE: “Seeing and Believing: Christian Imagery in Painting Now,” a roundtable conversation with four artists moderated by Emily Watlington: Religion is the theme of the December 2022 issue of the influential contemporary art magazine Art in America, and its cover story is a conversation with painters Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, Tammy Nguyen, Alina Perez, and Jannis Marwitz on their “bold reinventions of traditional Christian iconography.” They discuss the generativity of Christian imagery, the power of sacred images, their favorite Christian paintings, the function of metal leaf in illuminated manuscripts, Jesus as recognizable not by his specific likeness but by body language and symbol, “revisiting and repurposing history” as “a core practice of decolonization,” and the role of storytelling and transcendence in art.

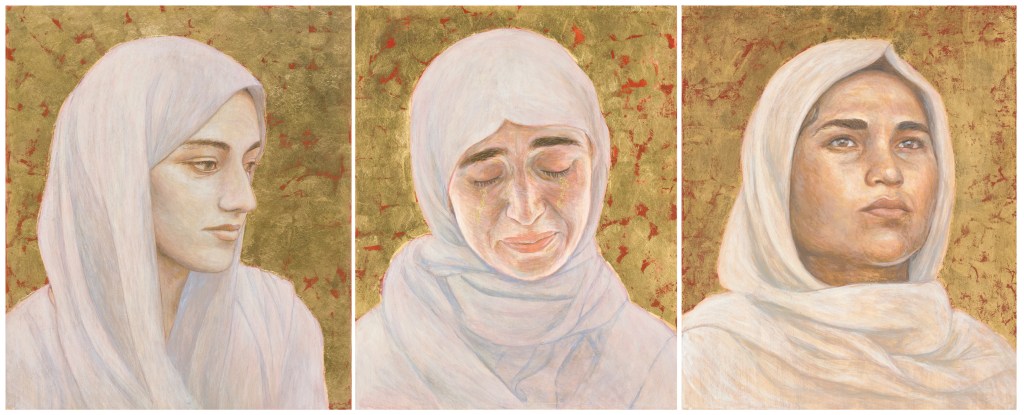

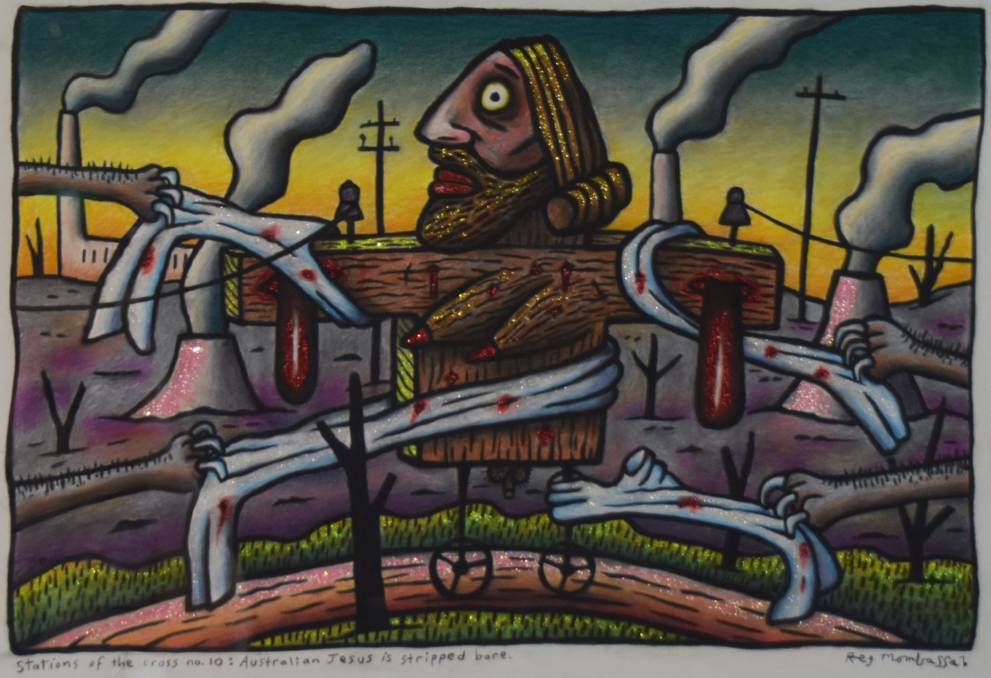

I especially appreciated being introduced to Nguyen’s work and hearing her thoughtful and nuanced perspectives. She mentions her Stations of the Cross series, inspired by her visit to the island of Pulau Galang in Indonesia to connect with her Vietnamese parents’ history as refugees on nearby Kuku Island following the Vietnam War. In the decommissioned Galang Refugee Camp, now a tourist site, fourteen golden Stations of the Cross statues are preserved in the forest, which served as devotional aids for the many Vietnamese Catholic refugees—but they are now overgrown by nature. Nguyen was struck by this tropical takeover, and her resultant body of work setting Christ’s passion in the jungle explores not only environmental agency but also legacies of colonialism and the important role of faith in circumstances of trauma and grief. Hear her discuss the series in this five-minute video that the gallery Lehmann Maupin put out:

I regret that besides Nguyen’s, all the other featured contemporary paintings in the Art in America article have only a very tenuous, sometimes indiscernible, connection to Christianity. Toranzo Jaeger’s End of Capitalism, the Future, a “queer utopia,” is based on Lucas Cranach’s Fountain of Youth—but Cranach’s subject (elderly women entering a pool to become young again) is not Christian, it’s mythological. And Marwitz’s The Raid supposedly references Caravaggio’s Madonna of Loreto, but I don’t see it at all, compositionally or otherwise. Perez mentions growing up Catholic in Miami, but that influence isn’t apparent in It Never Heals, unless we’re meant to read it in the painting’s flair for violence and drama. So the article’s subtitle, “Christian Imagery in Painting Now,” is a bit of a misnomer.

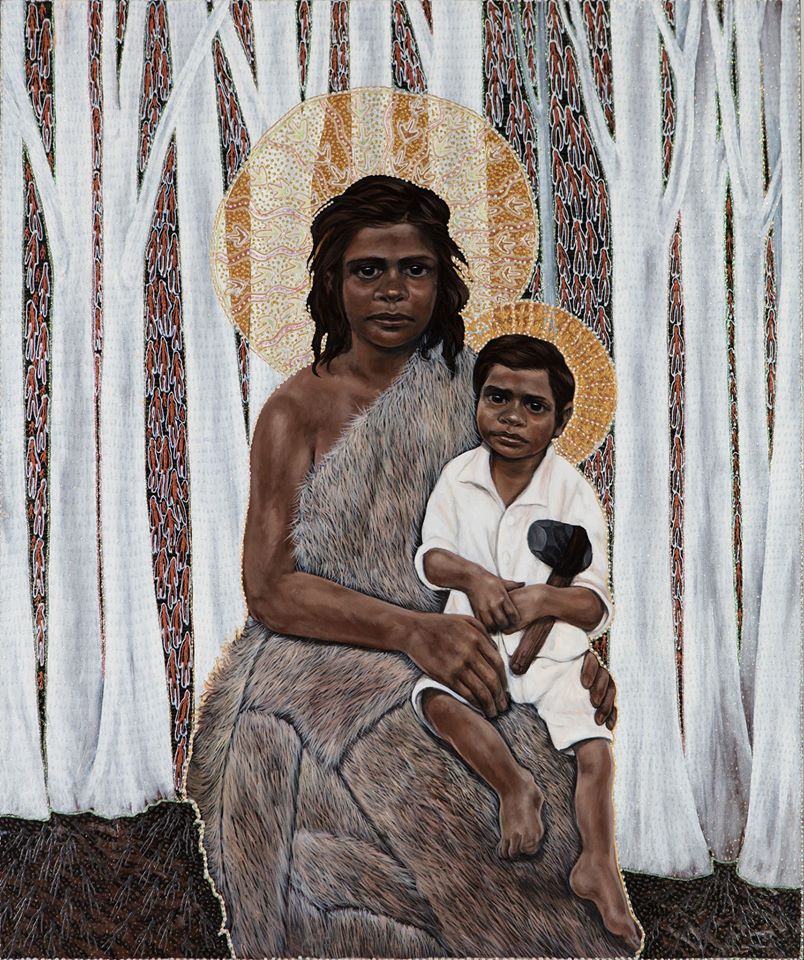

With the criteria of currently active painters consciously engaging with Christian imagery in ways that are not merely illustrative, I might have chosen to interview, for example, Jyoti Sahi (India), Daozi (China), Emmanuel Garibay (Philippines), Wisnu Sasongko (Indonesia), Marc Padeu (Cameroon), Harmonia Rosales (US), Stephen Towns (US), Rodríguez Calero (US), Trung Pham (US), Laura Lasworth (US), Patty Wickman (US), James B. Janknegt (US), Mark Doox (US), Sergii Radkevych (Ukraine), Ivanka Demchuk (Ukraine), Natalya Rusetska (Ukraine), Paul Martin (England), Filippo Rossi (Italy), Michael Triegel (Germany), Janpeter Muilwijk (Netherlands), Arne Haugen Sørensen (Denmark), Brett a’Court (Australia), or Julie Dowling (Australia).

I’m also disappointed that, from what I can tell from the interview, none of the four artists approaches their subjects from a place of Christian belief. I absolutely welcome non-Christians to engage with Christian stories and symbols—to play with them, reinterpret them, question them, or even use them as tools of critique or subversion. I just wish that in a conversation about ways that Christian imagery is being used today, the editors had thought to invite a Christian to the table, who could have provided a different viewpoint. But, kudos to Art in America for at least broaching the topic of religion in contemporary art!

+++

NEW STATUE: Antelope by Samson Kambalu: The fourth plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square is the prestigious site of rotating contemporary art installations, and from September 2022 to September 2024, it is home to Antelope by Malawian-born artist Samson Kambalu. This two-man bronze sculpture group reimagines a photograph of the pastor, educator, and revolutionary John Chilembwe (1871–1915) of Nyasaland (now Malawi) standing next to his friend John Chorley, a British missionary. Posing at the entrance of his newly built church, Chilembwe proudly wears a brimmed hat, flouting the law that Africans were not allowed to wear hats in the presence of their then colonial rulers. (Read more from Inno Chanza on Facebook, and from Harvard Magazine.) Kambalu’s sculpture shows the men facing away from each other instead of side-by-side, and he’s made Chilembwe almost twice as large as Chorley, elevating an underrepresented figure in the history of the British Empire in Africa.

After years of agitating peacefully against British colonial rule to no avail, Chilembwe led an uprising in 1915, which resulted in his death but which laid the seeds for Malawian independence. John Chilembwe Day is observed annually on January 15 in Malawi.

+++

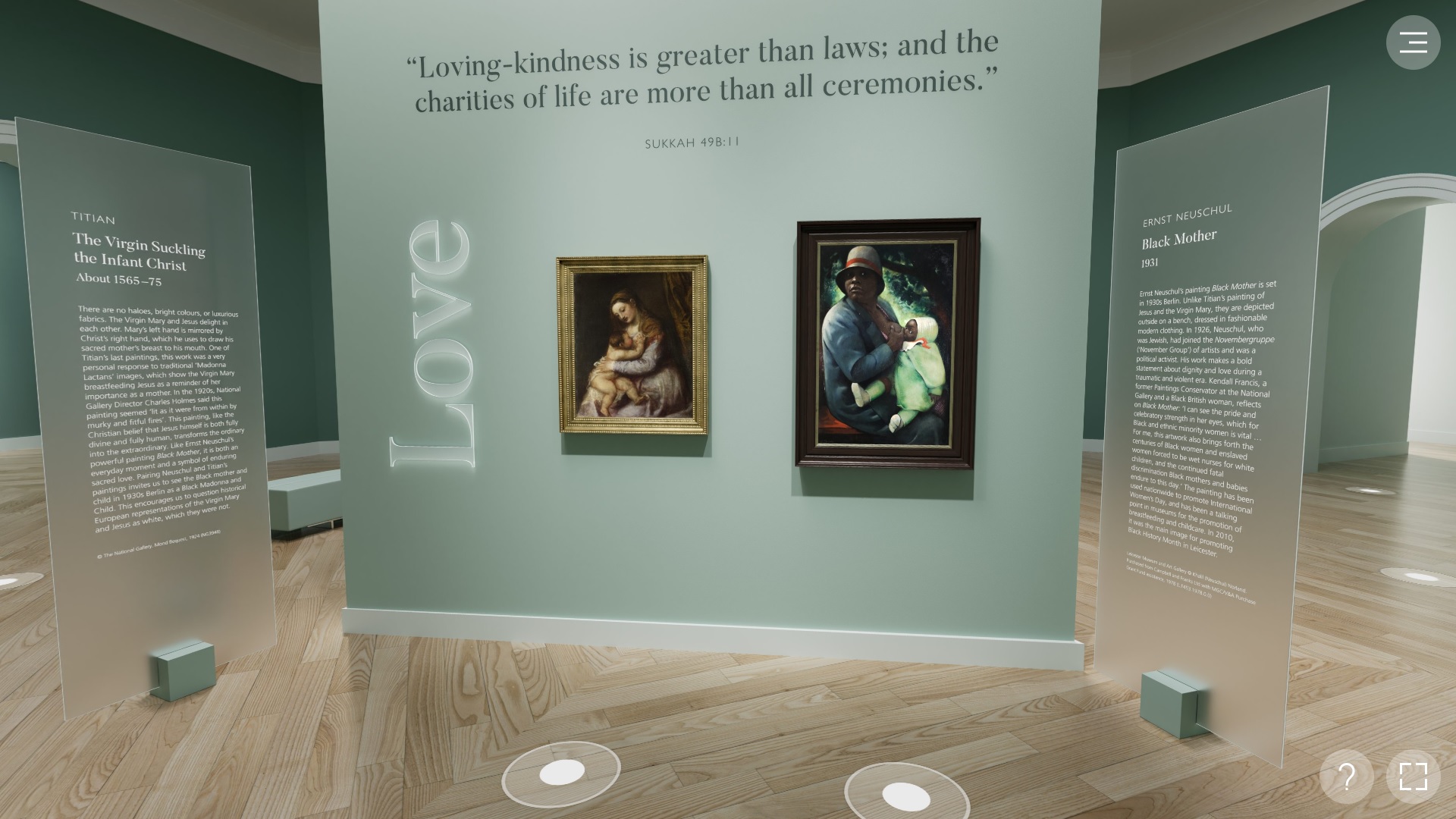

VIRTUAL EXHIBITION: Fruits of the Spirit: Art from the Heart: Curated by the Rev. Dr. Ayla Lepine as part of the National Gallery’s Art and Religion research strand, this new virtual exhibition was inspired by a passage from the apostle Paul’s letter to the Galatians, where he writes, “The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. There is no law against such things” (5:22–23). The exhibition pairs nine artworks from the National Gallery’s collection with nine from UK partner institutions that represent these spiritual fruits, these virtues, which are held in common across faith traditions. The Renaissance through contemporary eras are represented. [HT: Jonathan Evens]

Accompanying the exhibition is a web-based catalog (with contributions by theologians, activists, novelists, artists), an audio guide, and a series of in-person and online events from November 2022 through April 2023. Next up is a free online talk by the curator on January 30 at 1 p.m. GMT (8 a.m. EST).

+++

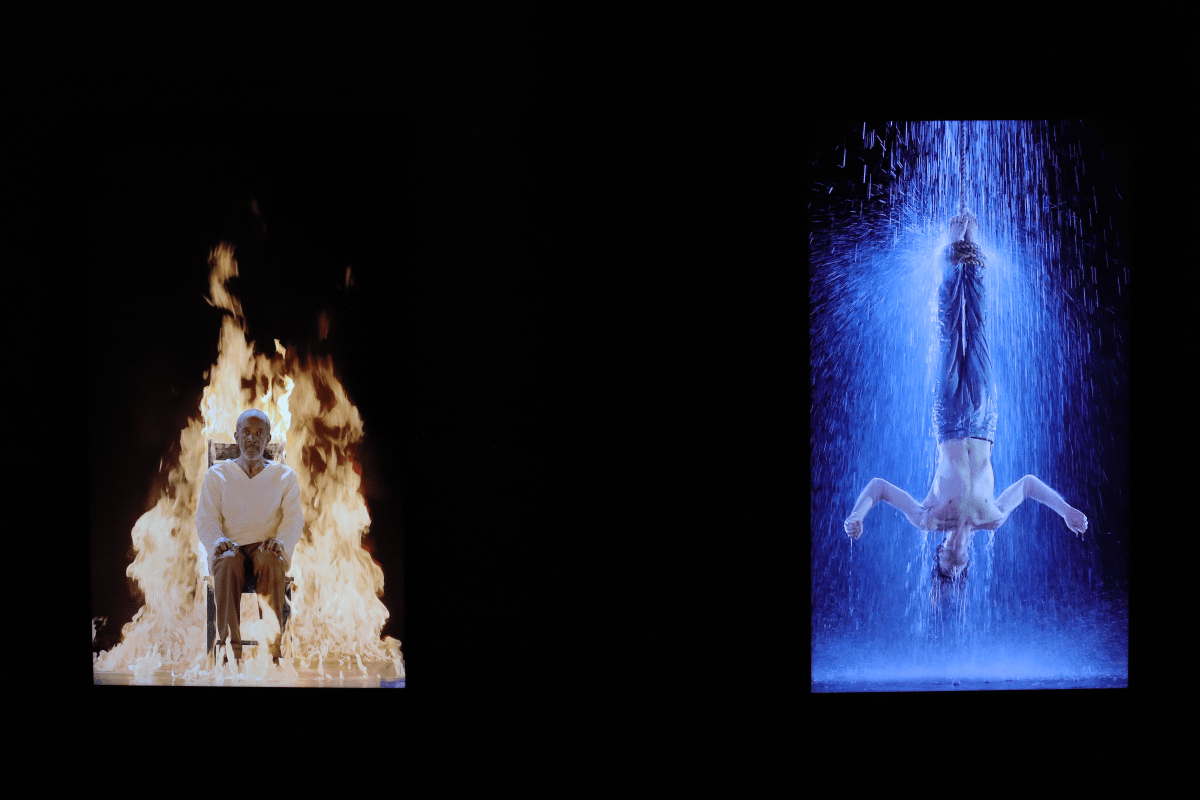

ARTICLE: “The Church of Secular Art” by David Carrier: “Bill Viola’s installation at a Naples church misses the spiritual mark,” reads the deck to this Hyperallergic article, a critic’s response to the Ritorno alla Vita (Return to Life) exhibition that ran from September 2, 2022, to January 8, 2023, at the Church of Carminiello in Toledo. The exhibition was organized by Vanitas Club, a Milan-based organization that throws artistic and cultural events in underutilized historic spaces, in collaboration with Bill Viola Studio.

I didn’t see the exhibition, but I’m familiar with Viola’s work [previously], and I don’t agree with Carrier’s assertions, if my understanding of them is correct. It sounds to me like he’s saying that when a sacred artwork—say, a medieval altarpiece—is transplanted to a museum, the work becomes secular, and that when a secular artwork is shown in a sacred space, rather than the space sacralizing the work, the work secularizes and thus undermines the space. It seems that he’s saying that art made in a contemporary idiom, like Viola’s video art, does not belong in churches, because it does not and cannot function as religious art. Art museums and churches have fundamentally different goals that are irreconcilable.

“The paintings and sculptures in Neapolitan churches are meant to support and strengthen the spiritual lives of believers; representations of St. Gennaro and other saints are intended to reinforce faith. The videos in Ritorno alla Vita call for a fundamentally different response. The exhibition website notes that these videos ‘exemplify the human capacity to transform and to bear extreme suffering and even death in order to come back to life through action, fortitude, perseverance, endurance, and sacrifice.’ These are important ideals, but they can apply equally to secular and nonsecular contexts.” The description Carrier quotes does seem to water down the art’s Christian content/messaging in an attempt to make the art more widely accessible. I’ve noticed that fault with some other displays of contemporary art in churches—where the curator, seeing their role primarily as one of hospitality to the wider (unchurched) community, underinterprets the art’s Christian angle. Though it can be difficult, there is a way to honor a work’s particularity and universality in the exhibition text.

I think we need to let art function differently for different viewers. Cannot a contemporary artwork, regardless of the artist’s intentions or where the art is placed, cultivate my affection for Christ as much as a traditional artwork? How I as a Christian read and experience Viola will differ from how an atheist does, and that’s OK. The same is true for a religious painting hanging in a national gallery—it may elicit prayer in me, boredom or contempt in another, emotional identification in another, purely aesthetic contemplation in another, and historical curiosity in yet another. I don’t think an image loses or gains its sacredness by its location, though I don’t underestimate the power of the staged environment to enable that sacredness to best shine through. I think that if the viewer receives a work as sacred, then it is.

That Viola does not depict specific historical saints in his Martyr panels—originally commissioned as a quadriptych by St. Paul’s Cathedral in London—does widen their interpretive horizon, but it doesn’t make them less “Christian.” I see the work as a memorial to all the unknown martyrs. I think of all the contemporary Christian martyrs around the world whose names I do not know, who have died with Christ’s name on their lips and his Spirit within them, and am prompted to intercede immediately for believers suffering religious persecution in their countries, who worship Jesus under threat of imprisonment or execution.

+++

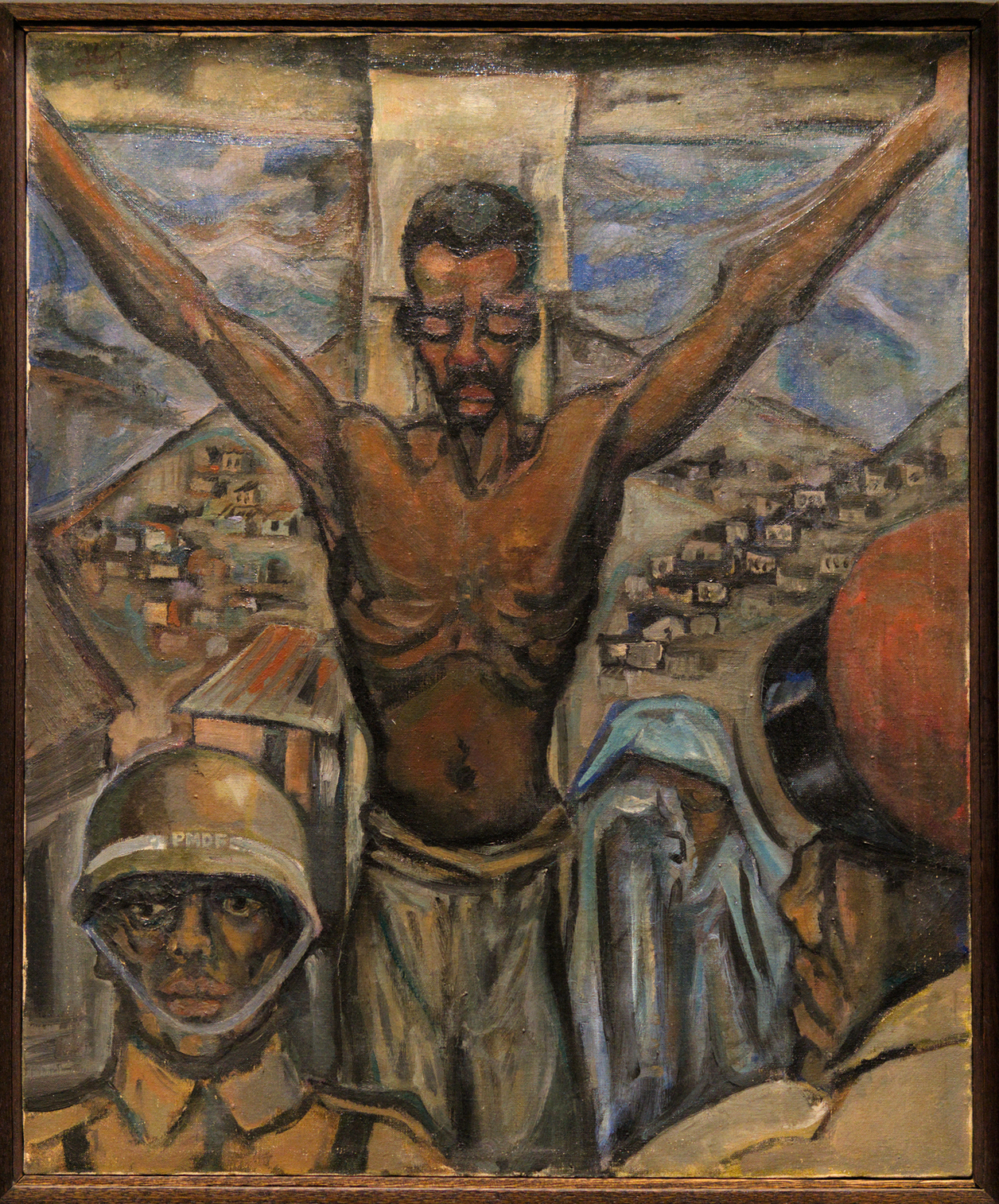

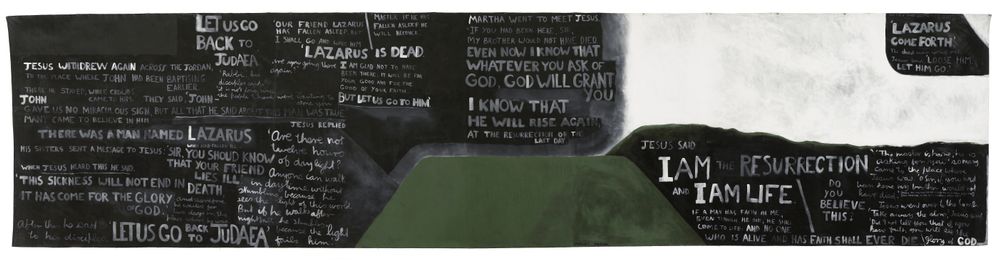

ARTICLE: “Openness to the world: Wes Campbell and his disturbing illusions of peace” by Jason Goroncy: In December 2022 theology professor Jason Goroncy spoke at the opening of a retrospective of the paintings of the Rev. Dr. Wes Campbell, hosted by Habitat Uniting Church in Melbourne. That talk is adapted here on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Religion and Ethics web portal. Campbell is a retired Minister of the Word in the Uniting Church of Australia with experience in parish ministry, university chaplaincy, UCA synod and assembly roles, and a sustained commitment to peace, justice, and social responsibility. His roughly three decades of art making was integrally connected to these roles, as through his paintings he expounds a faith-fueled poetics of hope, “bearing witness to the trauma of creaturely existence alongside a refusal to abandon the world to its violence, nihilism, and despair.”

“Wes’s art . . . does not shy away from the risky boundaries where hope is threatened, sustained, lost, and birthed,” Goroncy says. “It, therefore, embraces the tragic and the ugly, as well as joy and beauty. Whether his subject matter is the human condition, or explicitly religious stories (such as the nativity or the transfiguration), or the Earth itself, Wes’s work is replete with this kind of fidelity to the contradictions that mark our lived experience. . . . It embodies the conviction that the arts can unmoor us, disrupt the worlds we assume, facilitate our lament, and open up possibilities for futures we hardly dare imagine.”

+++

PODCAST EPISODE: “Victoria Emily Jones: Art & Theology”: In early December I spoke with Luminous podcast host Peter Bouteneff, a systematic theology professor and the founding director of the Institute of Sacred Arts at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, about my work at Art & Theology. We discuss how I got into this cross-disciplinary field, definitions of “sacred art,” and more.

Bouteneff earned his DPhil in theology from Oxford University under the supervision of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware. Besides theology, he also has an academic background in music, having studied jazz and ethnomusicology at the New England Conservatory. He has written two books on the music of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt.

I’ve been following the podcast since its inception in 2021. My favorite episodes are the ones with poet Scott Cairns; artist Bruce Herman; art historian Lisa DeBoer, author of Visual Arts in the Worshiping Church; curator Gary Vikan, a specialist in Byzantine art and the director of the Walters Art Museum from 1994 to 2013; and historian Christina Maranci, an expert on the development of Armenian art and architecture. Browse all the episodes here.