The medieval manuscript known as the Eton Roundels is a brief typological picture sequence produced in the English Midlands (possibly Worcester) in the mid-thirteenth century. Typology is a mode of Christian biblical interpretation in which certain Old Testament figures, events, or objects are seen as foreshadowing New Testament figures or events, especially Christ. Art historian Avril Henry says the Eton Roundels came into being at about the same time as the Biblia pauperum, a tradition of picture Bibles forming the largest and best-known compendium of typological imagery and verses.

The Eton manuscript consists of twelve pages of pictures, each with a large roundel at the center picturing a New Testament event (the “antitype”) and four surrounding smaller roundels depicting the Old Testament (and occasionally classical) “types” and prophets. Each page also includes a half-roundel on the left and right inhabited by anonymous figures who probably simply represent onlookers. A crowned female Virtue is seated at the bottom of each page, under whom is written a biblical commandment whose relevance to the pictures is sometimes difficult to discern. These pages are bound together with an Apocalypse, but it’s unknown whether the two works were conceived together from the start; it’s only certain that they were combined by the late seventeenth century.

The maker, scriptorium or city of origin, original recipient (and whether religious or lay), and purpose of the Eton Roundels are also unknown. Presumably the manuscript’s function was meditational.

The artist didn’t invent any of the typological correspondences illustrated in the roundels; they were all already common currency.

Below are the two Resurrection-themed pages, with a breakdown of the illustrations, including translations of the Latin inscriptions. The translations are by Avril Henry and are from his book The Eton Roundels: Eton College, MS 177 (‘Figurae bibliorum’)—A colour facsimile with transcription, translation and commentary (Scolar Press, 1990). This book is an excellent resource for learning more about the manuscript and is the only place I’m aware of where you can view all twelve pages.

Thank you to Sally Jennings, Collections Administrator at Eton College Library, and Dr. Carlotta Barranu, Library Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the time of my research, who provided me with photographs and translations prior to my gaining access to Henry’s book.

Folio VIII (5v)

↑ Center: Three Women at the Tomb (Mark 16:1–8)

“Because God came forth and God lives after burial, the event filled with mystery is the key to the tomb.”

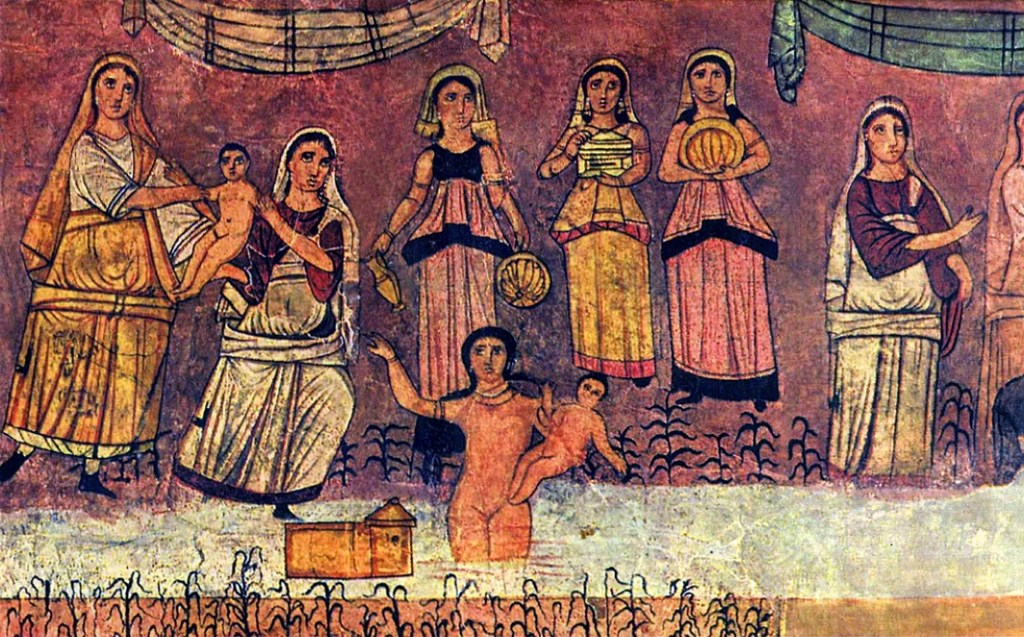

↑ Top left: Jonah Leaves the Fish (Jonah 2:11; cf. Matt. 12:38–41)

“Jonas. Just as he whom the belly of the sea-creature had enclosed is brought forth unharmed, at a glorious command life rose up from the tomb.”

↑ Top right: A Lion Revivifies Its Young

“By [its] breath the lion brings its cub back to life.”

This statement refers to a piece of lore found in the third-century Physiologus and its descendants, the medieval bestiaries, according to which lion cubs are born dead but are brought back to life three days later by their father’s breath. This (fictitious) leonine behavior was seen to reflect the Father raising the Son from the tomb on Easter morning.

↑ Bottom left: Job and Jonah (Job 19:26; Jonah 2:7)

“Job: And in my flesh I shall see God my [savior].

Jonah: Thou shalt lift up my life from corruption, O Lord my God.”

↑ Bottom right: Samson’s Escape from Gaza (Judg. 16:1–3)

“The imprisoned Samson escaped from Gaza and his enemies. Christ the stone, whom the stone covered, rose from the tomb.”

This roundel portrays Philistine soldiers of Gaza encircling the city gate to kill Samson the Israelite. But Samson escapes their watch unharmed, in a dramatic episode depicted on the following page (see below). The scene here is rarely depicted, whereas what follows in the narrative—Samson carrying the gates of Gaza—was a popular type of the Resurrection. Notice how the soldiers parallel the sleeping ones in the central scene, both groups bested by God’s power.

Folio IX (6r)

↑ Center: Christ Opens Limbo (1 Pet. 3:19; 4:6; Eph. 4:8–10)

“The gates having been broken and the prince of death bound, the body of the elect is carried to the stars in the heavens.”

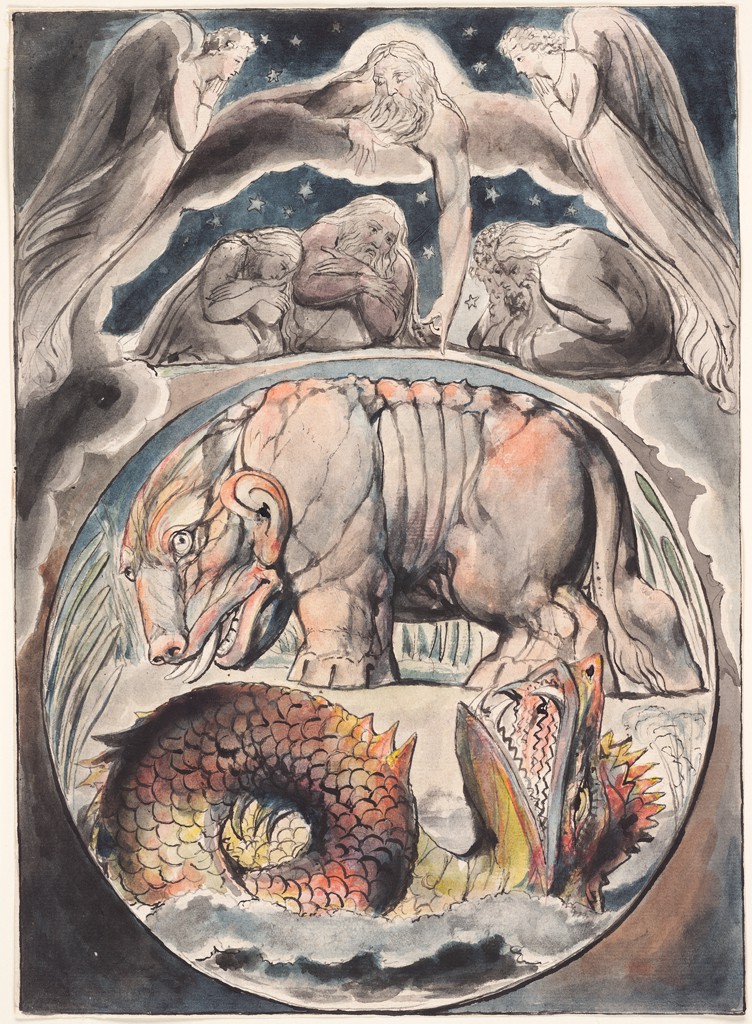

Christ’s Descent into Limbo, or the Harrowing of Hell, is an episode inferred from a few enigmatic biblical verses and elaborated in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, it is the primary icon of the Resurrection: Christ breaking down the gates of hell to rescue his predeceased beloveds from death and Satan. Medieval artists in the West were also fond of picturing the Harrowing, often portraying the entrance to hell as a monstrous maw (called a “hellmouth”).

↑ Top left: David Saves the Lamb from the Bear (1 Sam. 17:34–37)

“David. The bear is carrying off a sheep. David assists [the sheep], and takes it back. In the same way, man is saved by Christ and death is slain.”

David, who was a shepherd before he was anointed king of Israel, figures Christ in how he fiercely protected the lambs in his care, intervening to save them whenever they were snatched away by a lion or bear; he’d pry open the beast’s jaws, free the lamb, and then strike the beast dead, he relays to Saul. In a similar manner, Christ pried open the jaws of hell to save his precious sheep.

↑ Top right: Samson Kills the Lion (Judg. 14:5–8)

“Samson. The strength of Samson conquered the lion and tore [it] to pieces, and Christ conquers defeated hell together with the dragon.”

When Samson went down to the vineyards of Timnah to seek a wife, he encountered a fearsome lion, and “the spirit of the LORD rushed on him, and he tore the lion apart barehanded” (Judg. 14:6). This was Samson’s first display of divine empowerment.

↑ Bottom left: Hosea and the Erythraean Sibyl (Hosea 13:14; Augustine, PL XLI 579)

“Hosea: O death, I will be your death; O hell, I will be your torment.

Sibyl: The seeker will break the gates of the hideous underworld.”

The Sybilline Oracles is a collection of ancient Greek prophecies ascribed to the pagan sibyls (but many of which were actually written by Jews and Christians). Several of the church fathers cited them in defense of Christianity. The Erythraean Sibyl, for example, is said to have foretold the coming of Christ through an acrostic whose initial letters spell out “Ιησόύς Χριστός Θεου Ύίος Σωτηρ Σταύρος” (Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior, Cross). (See Eusebius’s Oration of Constantine, chap. 18.) She appears in the floor mosaic at Siena Cathedral, the stained glass at Beauvais Cathedral, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, the Van Eycks’ Ghent Altarpiece, and a number of other medieval and Renaissance Christian artworks.

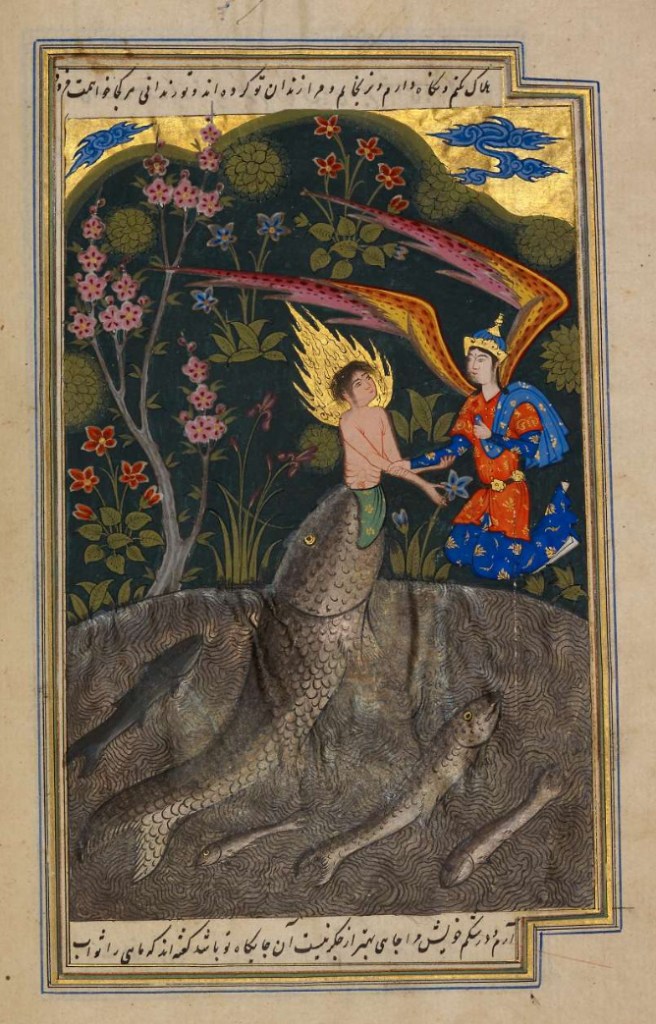

↑ Bottom right: Samson and the Gates of Gaza (Judg. 16:1–3)

“By carrying off the gates, Samson robbed Gaza. Robbing hell, Christ entered heaven.”

To break free of the Gazites, Samson tore the doors of the city gates off their hinges and carried them away, a demonstration of triumph. This feat prefigured Christ’s breaking out of his tomb. It can also be read, as on this Eton folio, as a prefigurement of Christ’s storming the gates of hell to release those held captive by the devil.