ART SERIES: Pallay: Andean Weaving of Liturgy and Design by Daniela Améstegui: Daniela Améstegui is a graphic designer from Cochabamba, Bolivia, who holds a master’s degree in theological studies from Regent College in Vancouver, with a specialization in Christianity and the arts. Her work “revolves around exploring faith, social justice, and Christian contextualization through design” and “reflects her commitment to using design as a tool for expressing and exploring theological concepts,” she says. She currently lives in Langley, British Columbia, with her husband and two young children, working as a freelancer.

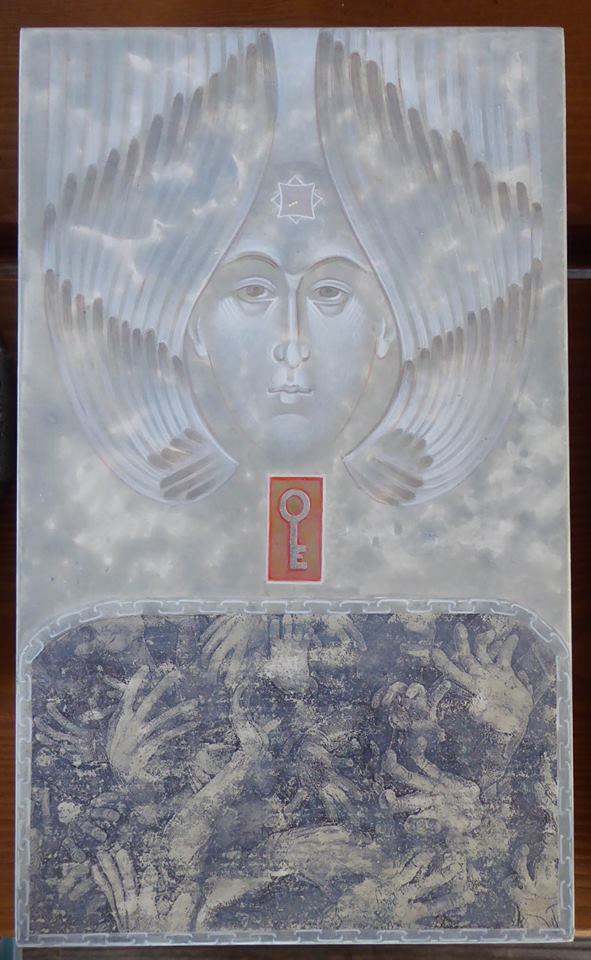

Améstegui’s final Integrative Project in the Arts and Theology for her master’s program was Pallay: Andean Weaving of Liturgy and Design, a series of seven digital illustrations, one for each of the major seasons/feasts of the liturgical year: Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, Pentecost, and Ordinary Time. The designs are inspired by Andean textile art and culture. You can view the full series at the link above from Regent College’s Dal Schindell Gallery, where the works were first exhibited in early 2022, but also listen to this wonderful online talk Améstegui gave about Pallay in 2020 for INFEMIT’s Stott-Bediako Forum, where she discusses not only her motivation and influences but also the content of each specific piece:

Whereas those of us in the northern hemisphere associate Advent with cold, darkness, and the onset of winter, in the southern hemisphere Advent falls in early summer, a time when the earth is most fertile and farmers plant their seeds. In her Advent design, Améstegui connects Mary carrying the seed of new life within her with Pachamama (Mother Earth).

In Bolivia, Christmas takes place during a season of harvest, so in her Christmas design, Améstegui places Jesus in the center between crops of corn and quinoa, the two main agricultural foods cultivated in the country. Mary wears braids and a bowler hat and Joseph plays the zampoña (Andean panflute), and at the bottom three cholitas, Indigenous women from the Bolivian countryside, gather reverently to greet the Christ child.

Améstegui does not have a website just yet but tells me she plans to launch one in 2025. If you would like to purchase one or more of her Pallay pieces, you can contact her at daniela@amestegui.com.

Thank you to blog reader Nicole J. for alerting me to this striking series!

+++

VIDEO COLLECTION: Casa del Catequista (CADECA) chapel paintings: As chance would have it, the same week I learned about Daniela Améstegui’s work, a different blog reader, Mark M., emailed me a link to some videos his Langham Partnership colleague Paul Windsor took during a recent trip to Bolivia. They record the many paintings, most by the late Quechua artist Severino Blanco [previously], inside the chapel of CADECA in Cochabamba, a place where men and women are trained as Christian leaders who then go out to serve their rural communities. They portray scenes from the Old and New Testaments, the parables of Jesus, and Latin American church history, including a remarkable liberation theology–inspired Resurrection, in which Jesus breaks down the doors of death and hell, holding high a cacique’s staff and leading the people of Bolivia into their future. Here’s a 360-degree view captured by Windsor, but visit the boldface link to see additional videos that narrow in on particular portions.

On the west end of the chapel (where people enter the space) is an Infancy of Christ cycle—reproduced here from a scan of a pamphlet, it appears. In the center is a Nativity, the Christ child painted over a pane of glass through which natural light comes gleaming in (see a closer view). The oblong shapes radiating out from the center are also glass, onto which the artist has (I think) etched lambs in various stages of prostration. On the sides, two villagers come with hot water and towels, and at the bottom two shepherds kneel before the Savior, removing their hats as a sign of respect. At the top, a host of angels with rainbow-colored wings and indigenous instruments sing Christ’s praises.

To the left of the Nativity are six scenes: (1) The Annunciation to Mary, (2) The Visitation, (3) The Annunciation to Zechariah, (4) The Journey to Bethlehem, (5) No Room at the Inn, and (6) The Flight to Egypt. To the right are (7) The Annunciation to the Shepherds, (8) The Annunciation to Joseph, (9) The Presentation in the Temple, (10) The Adoration of the Magi, (11) Jesus with the Scholars in the Temple, and (12) The Massacre of the Innocents.

+++

SONGS:

>> “Admirable Consejero” (Wonderful Counselor) by Santiago Benavides: Santiago Benavides is a Colombian singer-songwriter living in Toronto. On his Facebook page he describes his musical style as “trova-pop-bossa-carranga worship.” This song he wrote is a setting of Isaiah 9:2, 6–7 in Spanish. In the video, he’s the guitarist with the red-tinted glasses.

>> “The Word Became Flesh” by John Millea: John Millea is “a storyteller with a guitar,” singing in the tradition of Americana, folk, and gospel “about life and all of its joys, sorrows, and struggles.” He’s one of the artists I support through Patreon. This was the first song of his I encountered, and it’s one of my favorites, engaging with John 1:1–3, 14 in a wholly unique way!

In contrast to everyone and everything else in the universe, Millea explains, God had no beginning point, and all that is can in some way be traced back to him, the first link in a massive chain of cause and effect. So here Millea playfully traces his guitar all the way back to God—from the store he bought it at in Illinois, to the factory in Pennsylvania they ordered it from, to the mill in Washington that supplied the wood, to the Alaskan forests whence the tree was logged, and so on and so forth, imagining many thousands of years of fallen and dispersed tree seeds that traversed seas and continents, with an ultimate source in a tree planted in Eden by the Word of God.

When he hits on Eden, he starts moving forward again, through the story of creation, fall, and redemption in Christ, the divine beginningless One who graciously and mysteriously entered human history, born of a woman named Mary.

>> “Mary Had a Baby”: Arranged by Roland Carter, this African American spiritual is performed by the Nathaniel Dett Chorale, featuring the amazing mezzo-soprano Melissa Davis. It’s from their 2003 album An Indigo Christmas, the tracks taken from two live concerts given at the Church of St. George the Martyr in Toronto.

>> “Що то за предиво” (Shcho to za predyvo) (Behold a Miracle): This Ukrainian folk carol is performed by Trioda (Тріода), a musical group consisting of Andrii Gambal, Volodymyr Rybak, and Pavel Chervinskyi.

What is this awe-inspiring miracle?

There is great news on earth!

That the Virgin Mary gave birth to a son.

And upon birthing him, she declared,

“Jesus—my son!”And the aging Joseph stands nearby in awe

Of Mary having given birth to a son.

And he prepares the swaddling for Jesus Christ.

And Mary swaddles him, and scoops him to her heart—

The pure Virgin Mary!Trans. Joanna (Ivanka) Fuke [source]