ORIGINAL MIDDLE ENGLISH:

Vndo þi dore, my spuse dere,

Allas! wy stond i loken out here?

fre am i þi make.

Loke mi lokkes & ek myn heued

& al my bodi with blod be-weued

For þi sake.

Allas! allas! heuel haue i sped,

For senne iesu is fro me fled,

Mi trewe fere.

With-outen my gate he stant alone,

Sorfuliche he maket his mone

On his manere.

Lord, for senne i sike sore,

Forʒef & i ne wil no more,

With al my mith senne i forsake,

& opne myn herte þe inne to take.

For þin herte is clouen oure loue to kecchen,

Þi loue is chosen vs alle to fecchen;

Mine herte it þerlede ʒef i wer kende,

Þi suete loue to hauen in mende.

Perce myn herte with þi louengge,

Þat in þe i haue my duellingge.

Amen.

MODERN ENGLISH TRANSLATION:

“Undo thy door, my spouse dear,

Alas! why stand I locked out here?

For I am thy mate.

Look, my locks and also my head

And all my body with blood bedewed,

For thy sake.”

“Alas! alas! evil have I sped,

For sin Jesus is from me fled,

My true companion.

Without my gate he standeth alone,

Sorrowfully he maketh his moan

In his manner.”

Lord, for sin I sigh sore,

Forgive, and I’ll do so no more,

With all my might I forsake my sin,

And open my heart to take thee in.

For thy heart is cleft our love to catch,

Thy love has chosen us all to fetch;

My heart it pierced if I were kind,

Thy sweet love to have in mind.

Pierce my heart with thy loving,

That in thee I may have my dwelling.

Amen.

This poem appears in the 1372 “commonplace book” of the Franciscan friar John of Grimestone, who lived in Norfolk, England. Commonplace books were notebooks used to gather quotations and literary excerpts, with entries typically organized under subject headings. Preachers often kept them for homiletic purposes, gathering potential material for sermons. Grimestone’s is remarkable because it includes, in addition to much Latin material, 239 poems in Middle English. (English friars at the time regularly used vernacular religious verse in their sermons.) It is unknown whether Grimestone composed these verses himself or merely compiled them; likely, it is some combination. The first two stanzas of this particular poem are found, transposed, in another manuscript from almost a century earlier. Grimestone revised them slightly and added the third stanza.

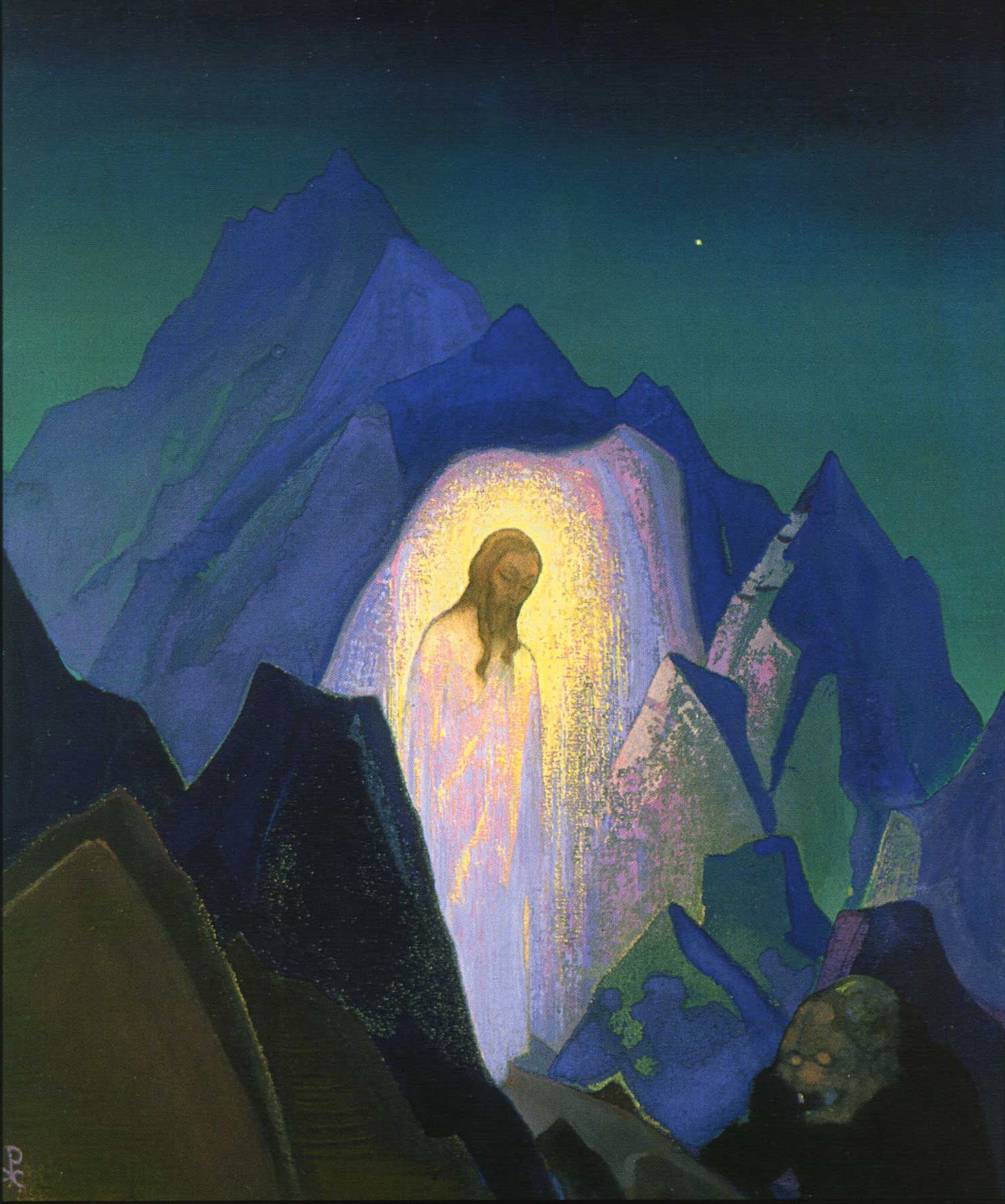

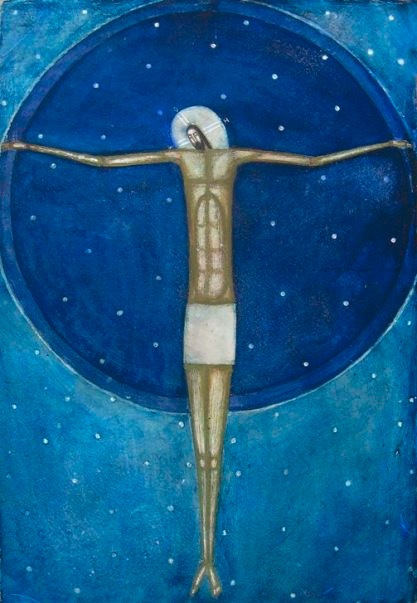

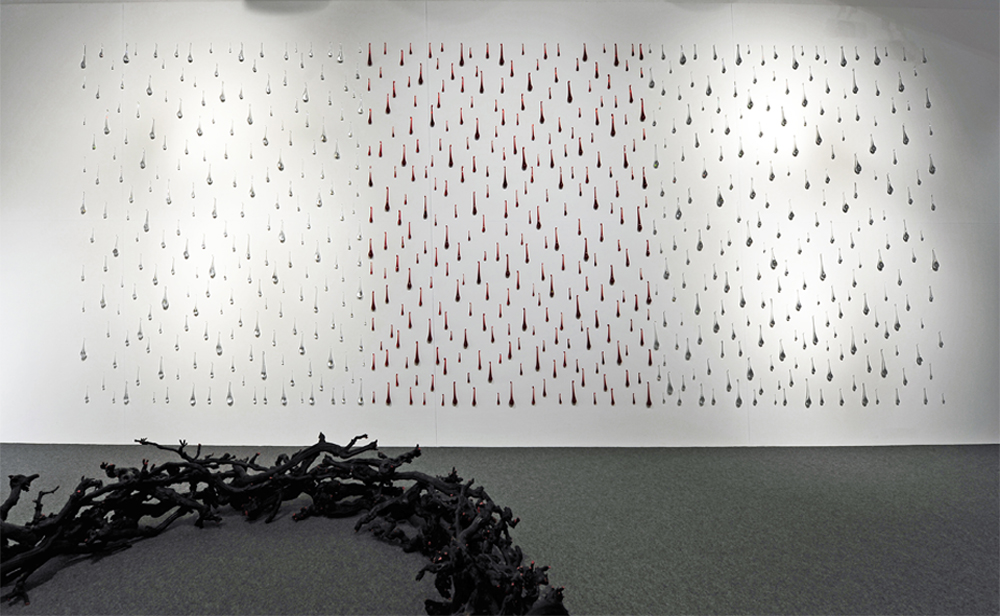

Belonging to the Christ-as-lover tradition, “Undo thy door” is based primarily on Song of Solomon 5:2, cited in Grimestone’s manuscript: “I sleep, but my heart waketh: it is the voice of my beloved that knocketh, saying, Open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled: for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of the night.” In a clever interpretation of the Old Testament source, the poet imagines the dewdrops on the Beloved’s brow as blood, thus identifying him with the thorn-crowned Christ. His bride is the human soul. Revelation 3:20 is provided as a further gloss by Grimestone: Jesus says, “Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.”

So in the poem, the speaker is keeping company with sin and has locked out her true lover, Christ. Christ stands at the gate of her heart and implores her with great ardor to let him in and to send sin packing. Wet with the wounds of sacrifice, tokens of his love, he is persistent in his longing for her.

Christ’s entreaties provide the impetus for the speaker’s repentance, expressed in the final stanza, which changes awkwardly in form and meter. His love has pierced her to the core, undoing her resistance. She resolves to break the sin-lock—to turn away from wrongful deeds—and answer Christ’s call so that they can enjoy sweet union together, dwelling in one another’s love. It was his heart that opened first—it was cleft by the centurion’s spear as he hung on the cross—and she is compelled to respond with similar openness, receiving what he has given, requiting his desire.

SOURCES:

This poem is #6108 in the Digital Index of Middle English Verse. It is preserved in Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland, Adv.MS.18.7.21, fol. 121v. A shorter, earlier version, from the late thirteenth century, appears in London, Lambeth Palace Library 557, fol. 185v.

Middle English transcription: Carleton Brown, ed., Religious Lyrics of the XIVth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924), 86

Modern English translation: David C. Fowler, The Bible in Middle English Literature (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984), 85–86

For further reading, see chapters 4–5 of Siegfried Wenzel, Preachers, Poets, and the Early English Lyric (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), especially pages 140–41; and chapter 7, “The Theme of Christ the Lover-Knight in Medieval English Literature,” in Rosemary Woolf, Art and Doctrine: Essays on Medieval English Literature (London: The Hambledon Press, 1986), especially pages 109–10.