I’ve been following the work of comics artist Madeleine Jubilee Saito for several years (you may recall me featuring her here and here), and I’m thrilled that her debut collection of comics, You Are a Sacred Place: Visual Poems for Living in Climate Crisis, has now hit shelves! It’s gorgeous, you all. To coincide with the book’s release date today, I asked if she’d be willing to write a guest post providing some background and insight on comics as an art form and how Christians, including herself, have used the form. Before sharing two of her own comics, she explores three earlier examples by others—an Italian Gothic devotional painting, a late nineteenth-century African American quilt, and (where my mind typically goes when I hear “Christian comics”) a popular series of evangelistic tracts—expanding my sense of what a comic can be.

—Victoria Jones

A guest post by Madeleine Jubilee Saito

Comics have always been an art form for ordinary people—the medium of children, the illiterate, and the learning-to-read.

Since the 1960s, underground comix have been a scrappy, democratic, DIY art form: anyone with access to a black-and-white printer can make their own eight-page zine. And many Christians have found that humblest of publications, the self-published evangelistic tract, in that humblest of locations: the bathroom stall.

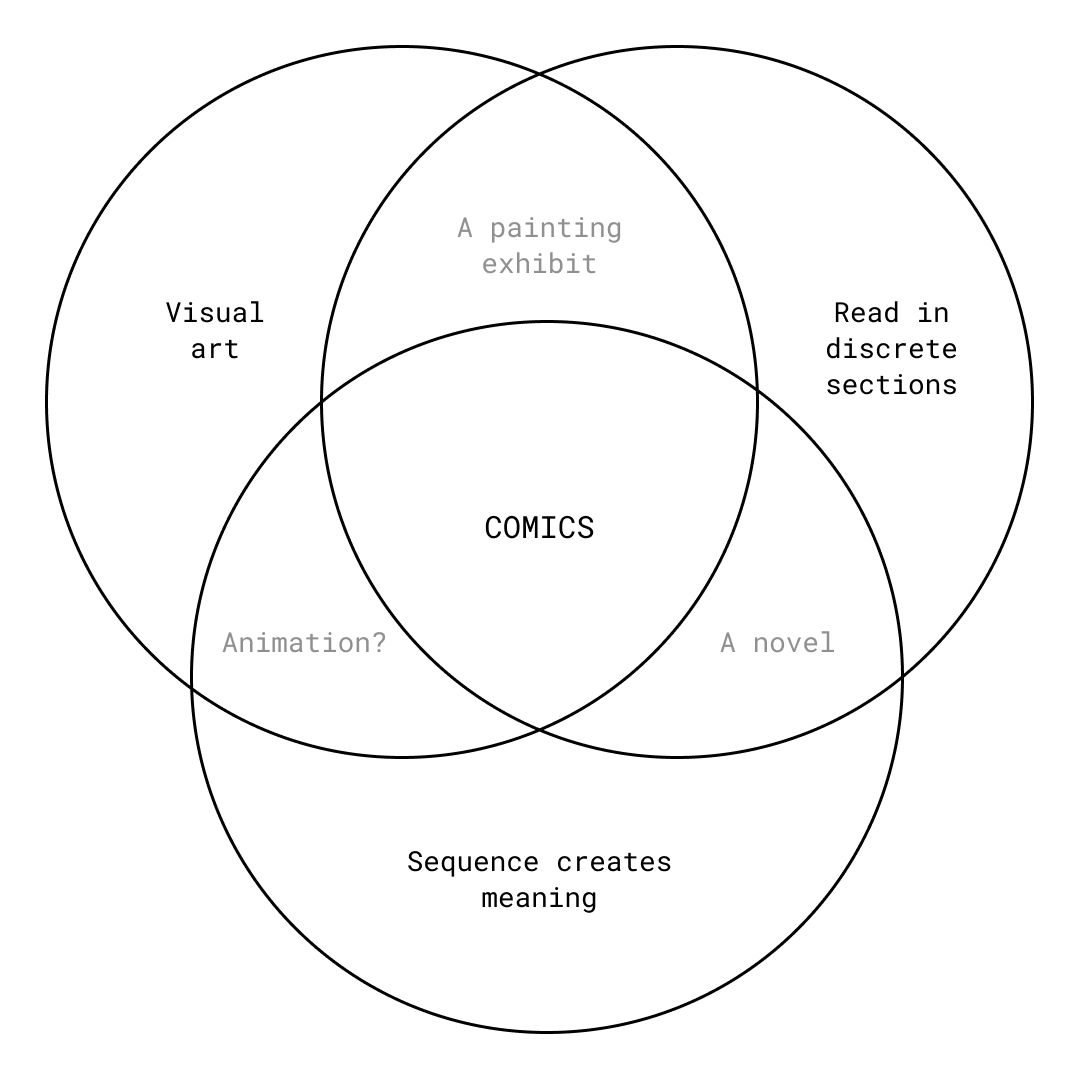

I am a Christian artist, and my medium is experimental comics. I define comics expansively as any visual artwork where meaning comes from the viewer reading discrete sections in sequence.

To put it more simply, comics are pictures (and sometimes text) that you read across panels.

Christian artists throughout time have been drawn to working in this medium. And because comics have always been a popular medium, often directed at those on the margins, reading Christian comics from the past can tell us something about how Christians of a particular time viewed ordinary people.

Three very different examples:

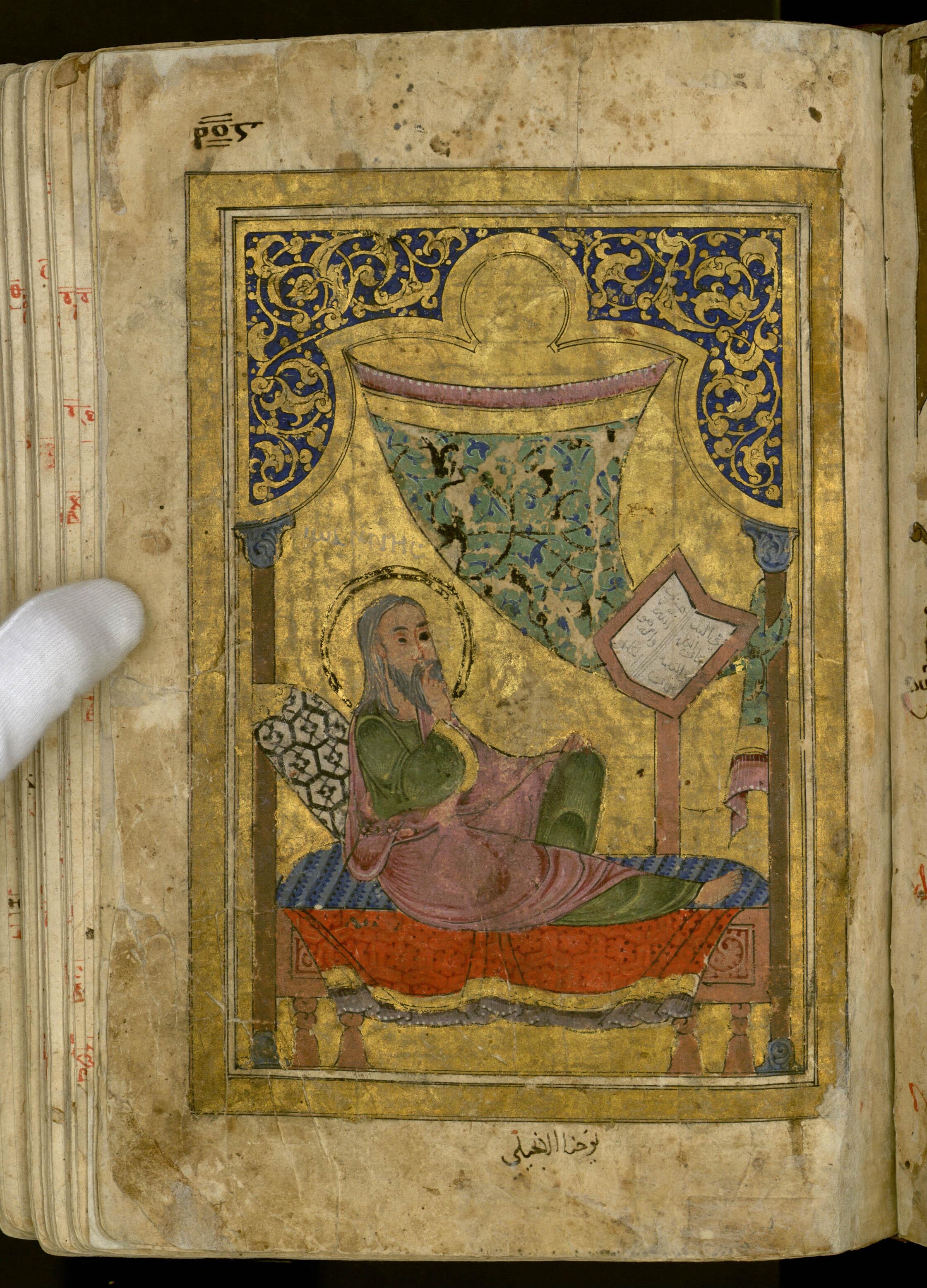

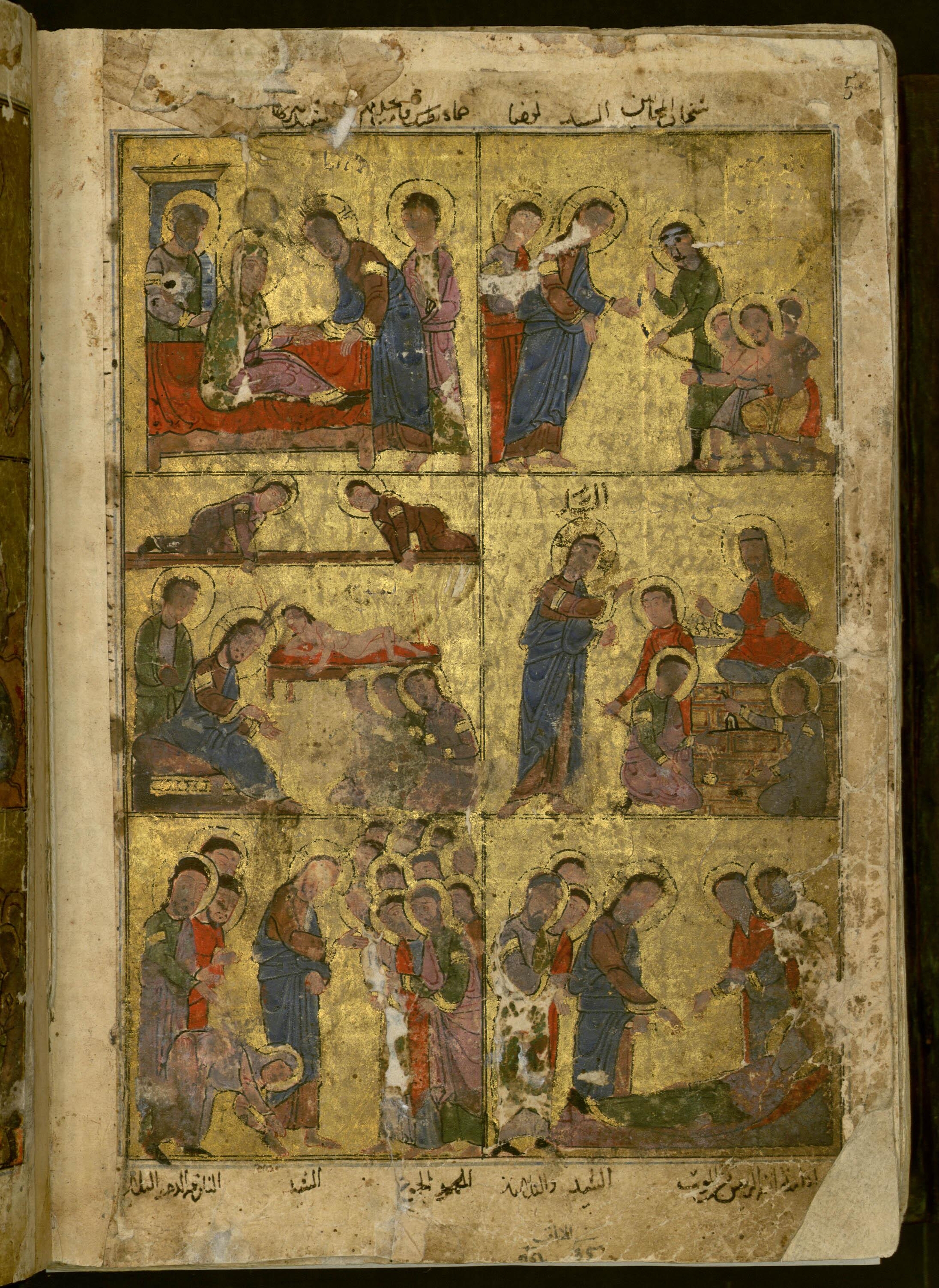

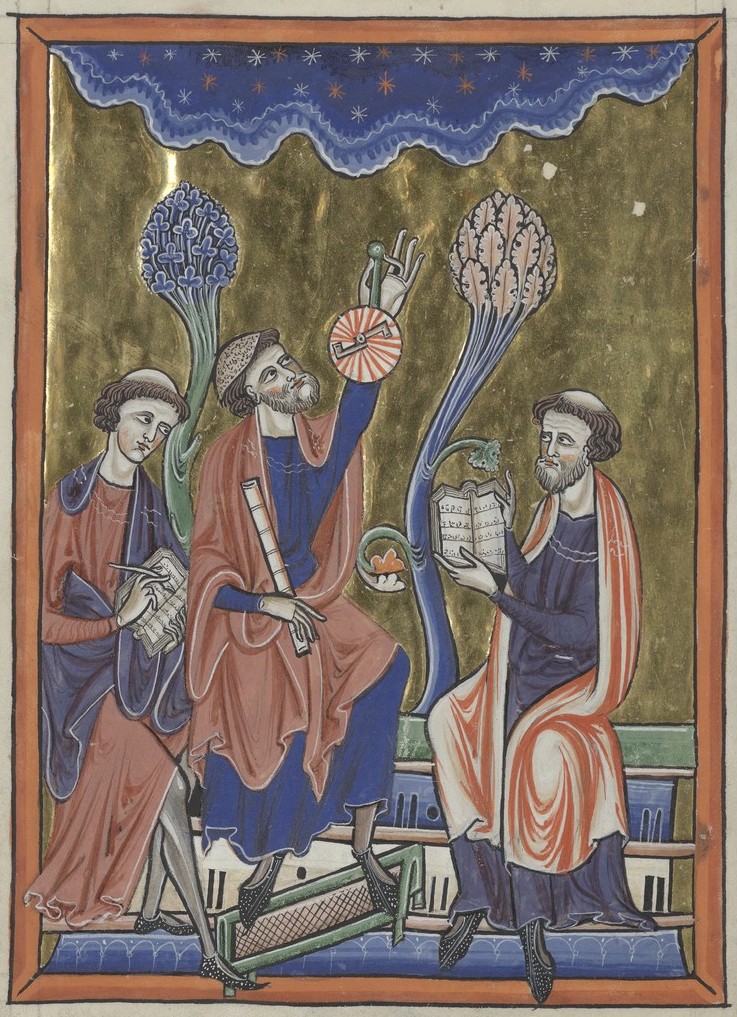

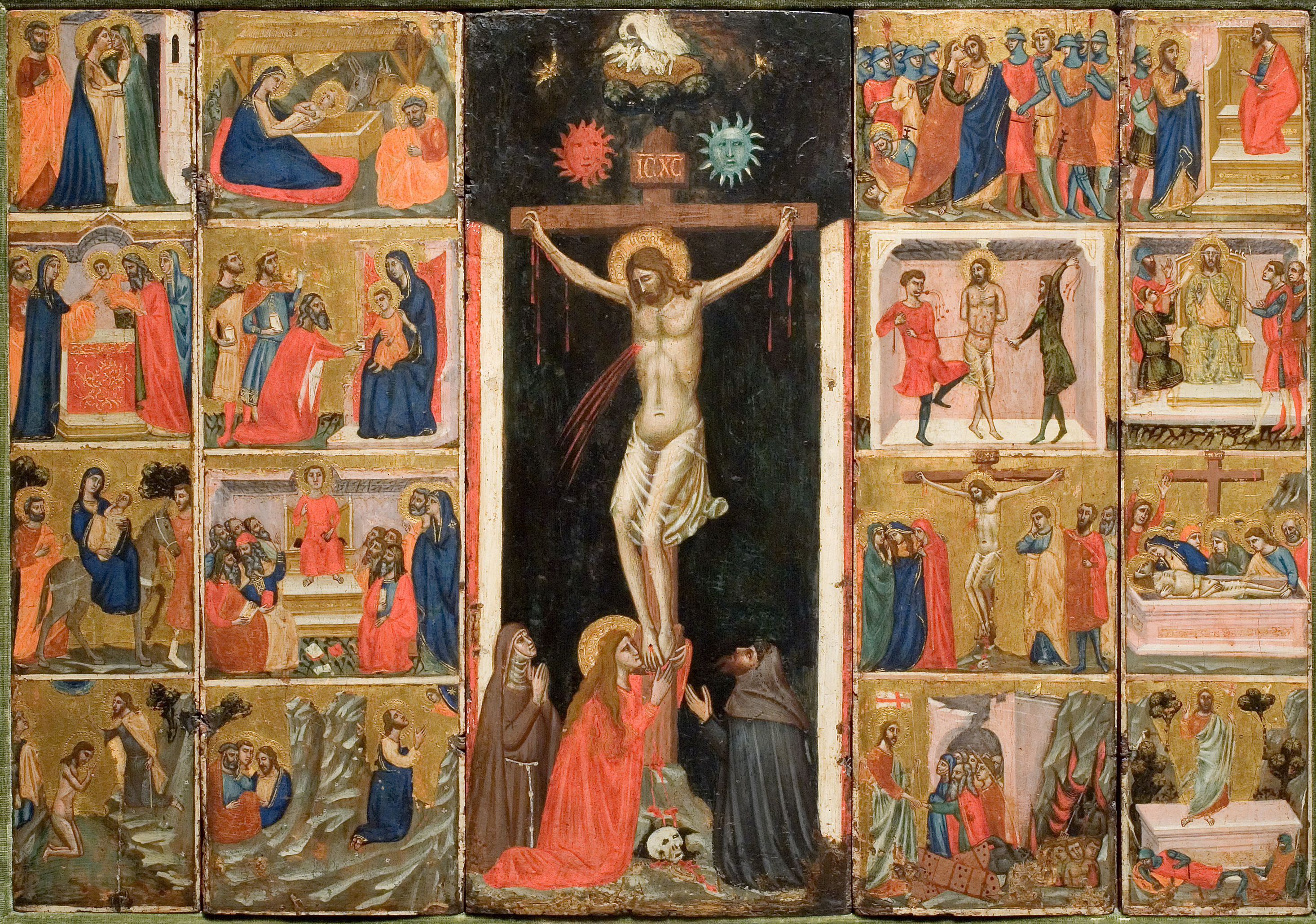

1. Pacino di Bonaguida, 14th century, Italy

Pacino di Bonaguida is one example of an Italian artist making sacred comics alongside the rise of the Dominican and Franciscan mendicant orders in the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries.

Panels showing sequential scenes from the life of Christ were a popular choice for altarpieces. (An example of artworks in this tradition is the Stations of the Cross—I made my own entry into that tradition a few years ago.)

In this period, Dominicans and Franciscans helped launch a movement in the church emphasizing preaching to and teaching common people and seeing oneself in the biblical story.

While we don’t have any writing from Pacino, we can look to the theological trends of the time to understand his comics.

The Dominicans and Franciscans encouraged ordinary Christians, including the illiterate, to move sequentially, systematically, through the story of Christ. The anonymously authored manual The Garden of Prayer (1454) instructs:

Alone and solitary, excluding every external thought from your mind, start thinking of the beginning of the Passion, starting with how Jesus entered Jerusalem on the ass. Moving slowly from episode to episode, meditate on each one, dwelling on each single stage and step of the story. And if at any point you feel a sensation of piety, stop: do not pass on as long as that sweet and devout sentiment lasts.

We see this sequential movement reflected in the sacred comics of the time—sometimes in square panels, other times in more creative shapes.

Sermons from the time extolled the usefulness of images depicting scenes from the life of Christ as a way to expand access to the gospel narrative. In 1492, for example, the Dominican friar Michele da Carcano, citing a famous letter of Pope Gregory’s from around 600, preached that images were introduced in churches “first, on account of the ignorance of simple people, so that those who are not able to read the scriptures can yet learn by seeing the . . . faith in pictures.”

These comics were intended to expand ordinary Christians’ access to the biblical story—making it more present and compelling, especially for those who couldn’t read.

2. Harriet Powers, 19th century, American South

Harriet Powers was a Black American quilter and folk artist who was born into slavery in 1837 and lived near Athens, Georgia.

Like the Dominicans and Franciscans several centuries earlier, Powers saw her comics as a more-than-verbal way to preach the gospel. She described her work as “a sermon in patchwork,” saying she intended to “preach the gospel in patchwork, to show my Lord my humility” and to “show where sin originated, out of the beginning of things.”

Powers’s comics teach and exhort, just like a sermon. In her article “Quilting the Sermon: Homiletical Insights from Harriet Powers,” Dr. Donyelle McCray places Powers’s visual art in the tradition of African American preaching:

Rather than preaching a discursive message, [Powers] offers one that is “archaic,” or “predicated on the priority of something already there, something given.” Her symbols and textures facilitate a process of “crawling back” to a deeper level of consciousness or evoking knowledge that is already within but encumbered. . . .

Powers focuses on what her audience already knows by nurturing memory and offering faith-enlivening symbols that will embolden their Christian imagination.

Powers’s quilts weave historical scenes from the recent past with biblical scenes—visually and metaphorically linking the biblical story and her immediate reality.

In her Pictorial Quilt, five of the fifteen panels depict recent historical and climatological events. The remaining ten depict stories from scripture.

Left: “The dark day of May 19, 1780. The seven stars were seen 12 N. in the day. The cattle wall went to bed, chickens to roost and the trumpet was blown. The sun went off to a small spot and then to darkness.“

Right: “The crucifixion of Christ between the two thieves. The sun went into darkness. Mary and Martha weeping at his feet. The blood and water run from his right side.”

Note the way that the visual repetition of celestial bodies creates a link between the scene of recent history and Christ’s passion.

Powers’s comics, written from the margins (Powers was a formerly enslaved woman in Reconstruction-era Georgia) and for those on the margins, reflect a vision of a world where biblical stories and lived reality are not distant or separate, but already intertwined.

God is already fully present on the margins. In “Quilting the Sermon,” McCray remarks:

A vibrant spirituality drives Powers’ preaching. She envisions God as a mighty sovereign who intervenes in earthly affairs and is known primarily through obedience to scripture and attentiveness to divine revelation. This revelation is not limited to scripture but continues to unfold in human history through climatological events, celestial occurrences, and everyday activities.

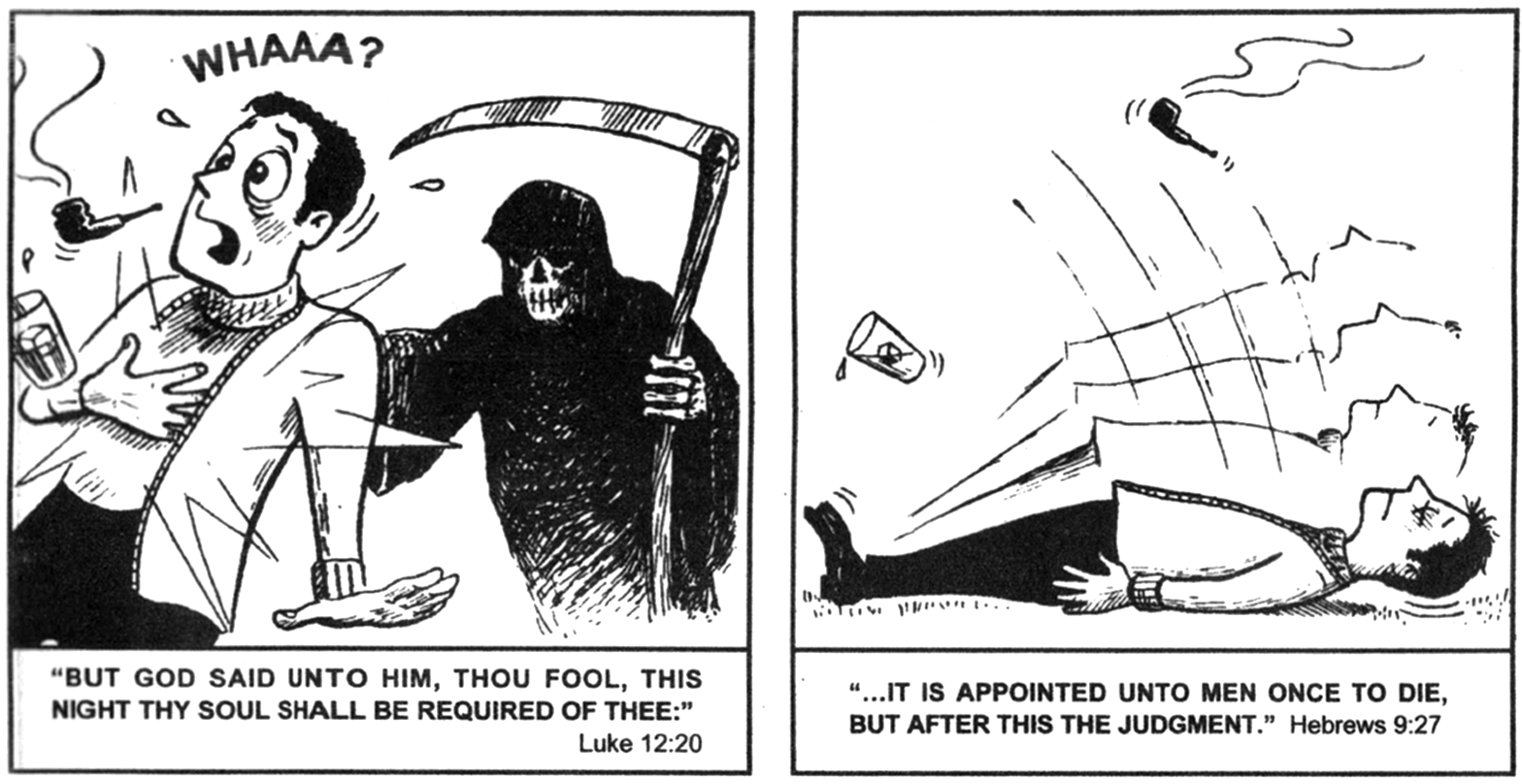

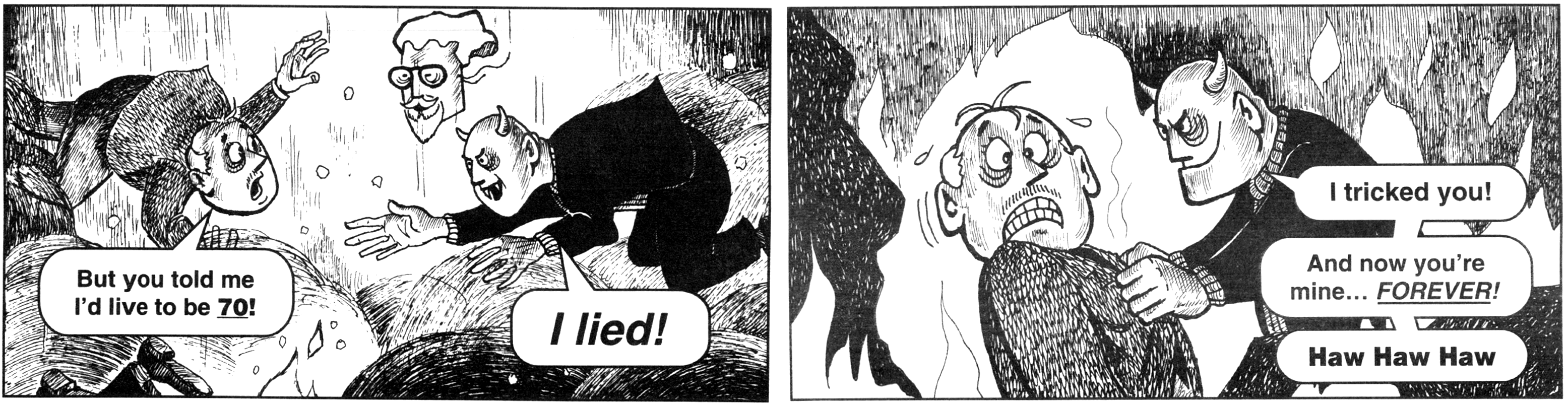

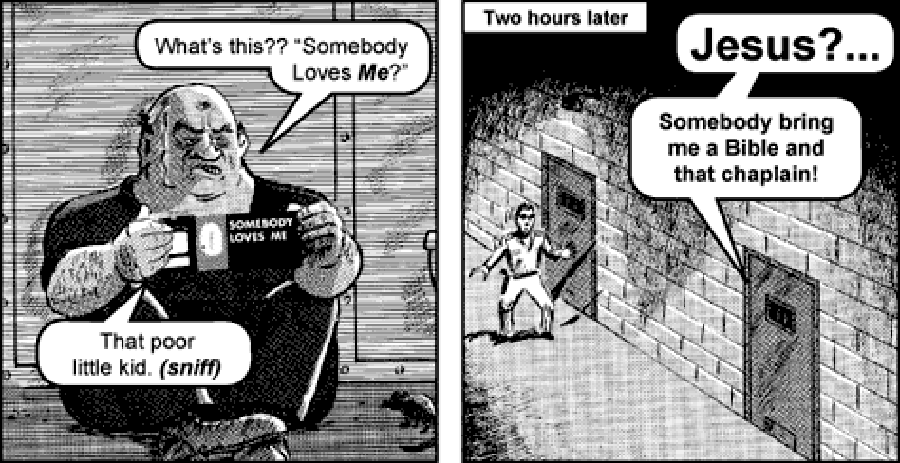

3. Jack Chick, 20th century, American West

Chick tracts are broadly viewed as hate literature because of their anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic content. And Jack Chick (and his collaborators) are likely among the best-selling cartoonists in human history, with one billion tracts sold (according to Chick.com’s numbers).

While I don’t commend Chick’s work for distribution or personal meditation, I think that a critical reading of his comics reveals something interesting about a particular tradition of American Christianity—and how that tradition views the ordinary people who encounter Chick tracts in their mailboxes and workplaces and on public bathroom floors.

Each tract is a little larger than a business card (3″ × 5″), and usually around twenty pages long. Most tracts have a consistent rhythm: a setup, a shocking encounter, and a dramatic conversion.

If reading the Stations of the Cross feels like solemnly walking behind Christ as he makes his way through Jerusalem, Chick tracts feel like being pushed off a cliff.

In Chick’s imagination, the reader’s encounter with Christ is flat, rote, and tightly choreographed: Chick gives his readers the words to say. The reader’s encounter with God is compressed and mass-produced—an industrial object, like the tracts themselves.

For all three artists—Pacino di Bonaguida, Harriet Powers, and Jack Chick—the form’s legibility, irresistibility, and overall accessibility made comics a compelling tool to facilitate their readers’ encounters with God.

When I started making comics in high school, I was drawn to the medium for similar reasons: there is something irresistible and magical about the format.

My first comics were influenced by the autobiographical cartoonists of the early 2000s, especially Kate Beaton and Marjane Satrapi. In recent years, I’ve begun working more experimentally, influenced by the tradition of Christian comics described above.

I’ve always loved the poetry and repetition of the Psalms and the Prophets. Comics, especially poetry comics, can have poetic resonances on multiple levels at once: in the text, in the imagery, and in the interplay between the text and imagery.

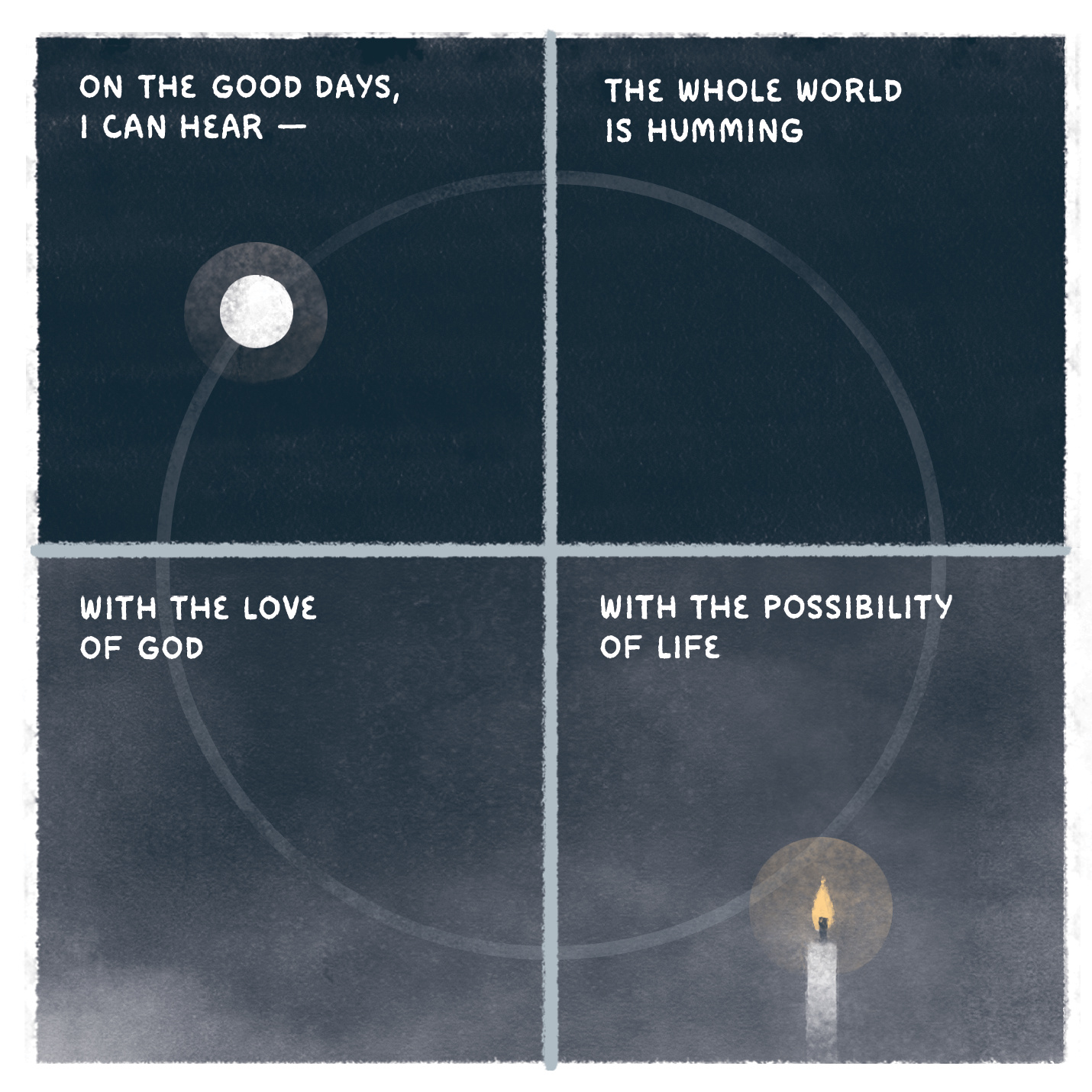

My first book, You Are a Sacred Place: Visual Poems for Living in Climate Crisis (out from Andrews McMeel March 25, 2025), is my attempt to bring the comics medium’s unique complexity into questions about the climate crisis, God’s justice, and how it feels to live in our moment in history.

Madeleine Jubilee Saito is a cartoonist and artist from rural Illinois living in Seattle and the author of You Are a Sacred Place (Andrews McMeel, 2025). In 2022, she was an inaugural artist-in-residence at On Being. Her comics open each section of the best-selling anthology of women’s writing about climate, All We Can Save (One World, 2020), and her work was recognized in Best American Comics 2019. Follow her on Instagram @madeleine_jubilee_saito.

[Purchase You Are a Sacred Place]

From the publisher: “In her debut collection of comics, artist and climate activist Madeleine Jubilee Saito offers a quietly radical message of hope. Framed as a letter in response to a loved one’s pain, this series of ethereal vignettes takes readers on a journey from seemingly inescapable isolation and despair, through grief and rage, toward the hope of community and connection. Drawing on the tradition of climate justice, Saito reminds readers that if we’re going to challenge fossil fuel capitalism, we must first imagine what lies beyond it: the beauty and joy of a healed world.”