LOOK: Peace Window by Marc Chagall

This stained glass window by Marc Chagall was commissioned as a memorial for the Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjöld (1905–1961), who served as the second secretary-general of the United Nations, and for the fifteen other UN staff and peacekeepers who died with him when their plane crashed on the way to a peace negotiation for the Congo Crisis in Northern Rhodesia. The artist’s handwritten dedication reads, “A tous ceux qui ont servi les buts et principes de la Charte des Nations Unies et pour lesquels Dag Hammarskjöld a donné sa vie” (To all who served the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter, for which Dag Hammarskjöld gave his life).

Chagall’s design was executed by master glassmakers Brigitte Simon and Charles Marq of Atelier Simon-Marq.

Chagall was born in 1887 into a Hasidic Jewish family in Vitebsk, Russia (now Belarus). He moved to Paris in 1910 to develop his art, becoming a French citizen in 1937. When Nazis took over the country, threatening Chagall’s safety, he was successfully extricated to the United States with the help of Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He returned to France for good in 1948. His impressive body of work, marked by a spiritual vivacity, includes—in addition to stained glass—paintings, drawings, book illustrations, stage sets, ceramics, and tapestries.

His 1964 Peace Window in New York City—not to be confused with his similar but much larger Peace Window of 1974 in the Chapel of the Cordeliers in Sarrebourg, France—is full of biblical allusions.

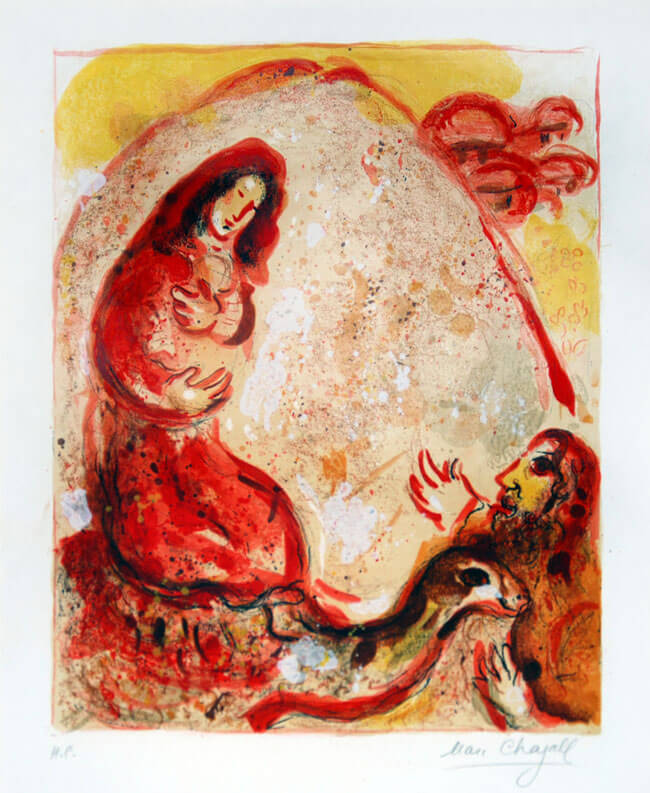

My eyes are drawn first to the red and purple bouquet in the center, under which stands an amorous couple. Who are they? What do they represent? I can think of several possibilities:

1. Adam and Eve. In the sketch Chagall made for the window, the woman is very clearly naked, though she’s less obviously so in the final window. That Eve, pre-fall, is traditionally portrayed unclothed, and that Chagall’s later Peace Window unequivocally portrays Adam and Eve within a red tree, lends credence to the interpretation of these figures as our primordial foreparents, in which case the flowering mass would stand for the tree of life in the garden of Eden (Gen. 2:9).

2. The Annunciation—the angel Gabriel coming to Mary to announce that she had been chosen to birth and mother God’s Son. The male head is bodiless, emerging from the crimson bloom (suggesting, perhaps, a supernatural entity), and there’s a yellow glow at the woman’s breast, perhaps signifying the conception of Christ. What’s more, the woman appears to be cradling something—her pregnant belly?

3. God and the human soul, or Christ and his church. One traditional Jewish interpretation of the poetic book of scripture known as the Song of Solomon is that it celebrates the love between humanity and the Divine. Medieval Christians, similarly, spoke of the book as an allegory of the future marriage of Christ and the church, his bride, drawing too on the New Testament book of Revelation, which culminates in a mystical union, a picture of cosmic harmony, heaven and earth inseparably joined.

4. The kiss of Justice and Peace. Psalm 85:8–11, a common Advent text, speaks of the divine attributes that coalesce to accomplish salvation (in the Christian reading, in the Incarnation):

Let me hear what God the LORD will speak,

for he will speak peace to his people,

to his faithful, to those who turn to him in their hearts.

Surely his salvation is at hand for those who fear him,

that his glory may dwell in our land.Steadfast love and faithfulness will meet;

righteousness and peace will kiss each other [emphasis mine].

Faithfulness will spring up from the ground,

and righteousness will look down from the sky.

5. The kiss of Joy. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was a favorite of Dag Hammarskjöld’s, and its performance, at least the “Ode to Joy” chorus in its final movement, is a United Nations Day concert tradition. Hammarskjöld described the work as “a jubilant assertion of life,” championing universal peace and brotherhood. One of the lines from Friedrich Schiller’s text that Beethoven set exclaims that “Joy . . . kiss[es] . . . the whole world!”

I suspect some or all of these ideas were at play when Chagall designed the window. Or even just romantic love in general (with other types of love portrayed elsewhere in the composition), as he often painted himself and his wife Bella kissing or embracing.

After this tableau, my eyes go to the large male figure cloaked in purple just right of center. I take him to be the prophet Isaiah, beholding a vision of wild animals and children cavorting together in harmony (see Isaiah 11). A boy, for example, reaches his hand out toward a viper and is not harmed.

But it’s also possible that’s meant to be Isaiah at the bottom left of the window, his face illumined by the beauty spread out before him, which an angel gestures to, guiding the prophet’s imagination:

On the top right, another angel delivers the Ten Commandments to the people of God.

Next to this communication of God’s word is the death of God’s Word in the flesh, Jesus Christ, around whom the crowds have gathered. A man ascends a ladder propped against the cross, the ladder being a multivalent symbol harking back to Jacob’s dream at Bethel and evoking notions of descent and ascent.

Vignettes below include a couple embracing with an infant in hand, a woman being fed at a table (the Eucharist?), a family reading a book (probably the Bible), a woman making music, and another bearing flowers.

At the top left is a lamentation scene that evokes those of Christ deposed from the cross. A man in a loincloth lies dead or wounded on the ground, his head cradled by a loved one, while at his feet another mourner throws her arms up in grief. This is the cost of human violence.

By contrast, in the bottom left corner, a mother cradles her child, evoking scenes of the nativity of Christ—of Mary with her newborn son.

All these characters—human, animal, and divine—are sprawled across a warm azure background, playing out love, suffering, death, peace, joy, and reconciliation.

When I visited the United Nations Headquarters last year, Chagall’s Peace Window was unlit and surrounded by construction, but a UN Facebook post from this September suggests that it is on view again. I’d love to see it in person and get some high-resolution photos of it. The majority of the detail shots I’ve posted here are cropped from a photo that Addison Godel (Flickr user Doctor Casino) took in 2016 when six of the forty panels were out for cleaning.

LISTEN: “Oracles” by Steve Bell, on Keening for the Dawn (2012)

O ancient seer, your vision told

Of desert highways streaming home

To the mountain of the Lord

Where nations sound a righteous song forevermore

And on that mountain men will forge

From cruel implements of war

The tools to till and garden soil

The rose will bloom and faces shine with gladdening oil

And it will surely come to pass

Justice will reign on earth at last

The wolf will lie down with the lamb

No beast destroy, no serpent strike the child’s hand

And God himself will choose the sign

A frightened woman in her time

Will bear a son and name him well

God with us! O come, O come, Emmanuel!