FIVE R’S FOR REFORMATION COMMEMORATION

As a guard against Reformed hubris, Churches Together in England has issued a statement urging churches to mark the Reformation’s fifth centenary with sensitivity to other branches of the faith, providing 5 R’s as guidelines. Keep the anniversary, it says, with the spirit of

Rejoicing – because of the joy in the gospel which we share, and because what we have in common is greater than that which divides; and that God is patient with our divisions, that we are coming back together and can learn from each other.

Remembering – because all three streams of the Reformation have their witnesses and one church’s celebration could be another’s painful memory; and yet all believed they acted in the cause of the gospel of Jesus Christ for their time.

Reforming – because the Church needs always to grow closer to Christ, and therefore closer to all who proclaim him Lord, and it is by the mutual witness of faith that we will approach the unity for which Christ prayed for his followers.

Repenting – because the splintering of our unity led us to formulate stereotypes and prejudices about each other’s traditions which have too often diverted our attention from our calling as witnesses together to the mercy of God in proclamation and service to the world.

Reconciling – because the call to oneness in Christ begins from the perspective of unity not division, strengthening what is held in common, even though the differences are more easily seen and experienced.

This is not to say we can’t celebrate the achievements of the Reformation (we certainly should!), but we ought not to do so with denigration toward our Catholic brothers and sisters, nor hold our own branch above reproof. All church history, before and after the major splits, is our history as a body. Read the full CTE statement here. For other initiatives to foster common witness, service, and understanding between Protestants and Catholics, see the documents “Evangelicals and Catholics Together” (1994) and “Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification” (1999).

+++

ECUMENICAL ARTS SYMPOSIUM

The last two weekends in October will cap off the international “Arts and Ecumenism” symposium organized by the Mount Tabor Ecumenical Centre for Art and Spirituality to commemorate the five hundredth anniversary of the Reformation. With events in Paris, Strasbourg, and Florence, the symposium is now coming to the US to continue the discussion on Catholic and Protestant approaches to art.

The penultimate session, “Sacred Arts in North American Contexts,” will take place October 20–21 at Yale University. “Arts in Celebration: The Word in Color, Action, Music, and Form,” the final session, will take place October 27–29 at the Community of Jesus in Orleans, Massachusetts, and will include demonstrations of mosaic, fresco, and Gregorian chant; lectures and panel discussions with Timothy Verdon, William Dyrness, Deborah Sokolove, and others; exhibits of contemporary sacred art by Susan S. Kanaga and Filippo Rossi (view the catalog); liturgies of the Divine Office and Holy Eucharist; an organ recital; and a fully staged presentation of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s opera The Pilgrim’s Progress, performed by the community’s critically acclaimed Gloriae Dei Cantores choir and Elements Theatre Company. Click here for the schedule.

I stayed at the Community of Jesus last week, and trust me, $425 is a great price for two days and nights at this beautiful Cape Cod monastery, with its Benedictine hospitality, and access to a high caliber of visual, musical, and dramatic art and prominent voices in the field of Christianity and the arts. But the best part, I think, will be the opportunity to inhabit the ecumenical vision the community has established, whereby all Christians—Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox—live together, eat together, and worship together. Some community members have taken vows of celibacy, while others have chosen marriage and live with spouse and children on the compound. Partaking of the Eucharist last Friday with brothers and sisters from other streams of Christianity and multiple generations was an experience I will not soon forget. Be sure to take advantage of the early-bird registration discount, which ends September 1.

(Click here to take a virtual tour of the Community of Jesus’s Church of the Transfiguration.)

+++

PAST LECTURE: “Visual Ecumenism” by Matthew Milliner: Milliner is an evangelical Anglican who teaches art history (his specialization is Byzantine) at a Protestant liberal arts college in Illinois. In this talk given April 7, 2017, at the Wheaton Theology Conference “Come, Let Us Eat Together!,” he discusses how we can “put on” other Christian traditions without losing our own by engaging their artistic output, by opening ourselves up to the material expressions of the gospel present all across the denominational spectrum:

I’m taking a particularly cherished part of my tradition—the law/gospel distinction—and showing that it can be found in other traditions as well. This might seem like I’m colonizing other traditions with my Protestantism, but I’m actually trying to strip my own tradition of its exclusive possession of this message and see it elsewhere, so that evangelicals can be at home in late medieval Catholic devotional manuals or in Russian Orthodox cathedrals. (19:04)

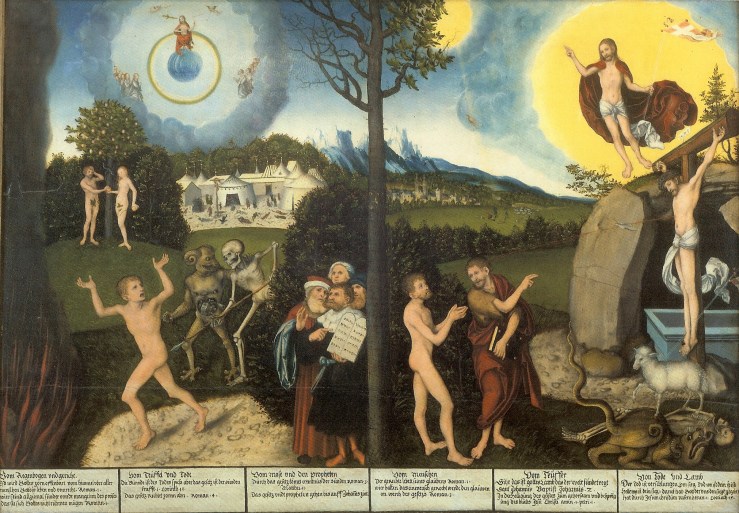

In reverse chronological fashion, he examines Lucas Cranach’s Law and Grace (Protestant), Berthold Furtmeyr’s Tree of Life and Death (Catholic), and the Sinai Pantocrator icon (Orthodox). Michelangelo’s late drawings and tomb for Pope Julius II are discussed in light of his involvement in the Spirituali, a Catholic reform movement in Italy that emphasized intensive personal study of scripture and justification by faith. More personally, Milliner describes how he was able to make it through repeated Hail Marys during a Catholic prayer service he inadvertently stumbled into one time and, on another Marian note, shares the Madonna of Mercy mural created last year by a group of Protestant art students he co-taught in Orvieto, Italy, with Bruce Herman, showing how they honored this subject that originated outside their tradition while also bringing it in line with their theological convictions—which, they discovered, were corroborated by Vatican II. In an earlier essay on visual ecumenism, Milliner wrote,

Just as there is, according to our Bibles, ‘one Lord, one faith, one baptism,’ so perhaps there is also one variegated yet unified Christian aesthetic, to which the different traditions, at their utter best, ascend. Full maturity (which for evangelicals has been a long time coming!) is not to see with Protestant, Orthodox or Catholic eyes—but with the eyes of Christ.

Milliner has given similar talks in the past: “Toward a Visual Ecumenism,” at Duke; “Toward 2017: Visualizing Christian Unity,” at George Fox; “Altars on the Jordan and the Rhine,” at the Institute for Ecumenical Research in Strasbourg; “Against Confessional Aesthetics,” at Baylor; and “Hearing Law, Seeing Gospel: A Mockingbird History of Art,” at the 2017 Mockingbird Conference. I hope they turn into a book!

+++

UPCOMING LECTURE: “An Evening with Ken Myers: Luther’s Artistic Legacy,” Saturday, September 9, 7:30 p.m., Wallace Presbyterian Church, College Park, Maryland: To kick off its second season, the Eliot Society has scheduled Mars Hill Audio founder Ken Myers to discuss Martin Luther’s contributions to Christian hymnody. “With the help of some local musicians, Myers will examine the artistic climate Luther helped to create, as well as some of the great composers of sacred music who followed after him. The lecture will argue that the pattern of Luther’s artistic engagement provides a model for contemporary efforts to reconnect faith and the arts.” Click on the link above to reserve your free ticket.

+++

FROM THE ARCHIVES: “An early Protestant painting (commissioned by Luther)”: On my previous blog I wrote a post about an altarpiece Martin Luther commissioned from his friend Lucas Cranach to promote Protestant theology. (It’s the same painting Milliner opens his above talk with.) Luther was more accepting of religious images than many of his fellow reformers, elucidating his position in his Invocavit Sermons (1522) and in the treatise Against the Heavenly Prophets in the Matter of Images and Sacraments (1525). I plan to feature vast swaths of these texts on Art & Theology in the near future.

The doctrine of the imago Dei—which states that human beings were uniquely created in the image of God and continue to bear that image—is central to Christian theology, for it tells us who (and Whose) we are. The book

The doctrine of the imago Dei—which states that human beings were uniquely created in the image of God and continue to bear that image—is central to Christian theology, for it tells us who (and Whose) we are. The book