Tomorrow’s readings in the Revised Common Lectionary, for the fourth Sunday of Easter, include what’s probably the most famous passage in the Bible, Psalm 23:

The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

In characterizing God as a shepherd, the psalmist expresses how God leads, protects, rescues, feeds, and cares for his own. The author of Psalm 95 uses the same metaphor when he writes, “For he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand” (v. 7)—as do Isaiah and Ezekiel. During his teaching ministry, Jesus described himself as “the good shepherd [who] lays down his life for the sheep,” and whose flock knows his voice and follows him (John 10:1–18).

There are hundreds of metrical paraphrases and musical settings of Psalm 23. I’ve compiled some three dozen of the best into a Spotify playlist, along with a handful of other songs that reference or adapt other biblical passages that speak of God as a shepherd. There are settings by Philippe Rogier, Franz Schubert, Antonin Dvořak, Noel Paul Stookey (of Peter, Paul and Mary), John Michael Talbot, Val Parker, David Gungor, Luke Morton, and others. Besides English, languages include Hebrew, Latin, Spanish, French, German, Czech, Arabic, Mandarin, Urdu, Swahili, and Sotho.

The Psalm 23 settings that are most widely reproduced in modern English-language hymnals are:

- “The Lord’s My Shepherd,” written by Francis Rous but extensively revised by committee and published by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in the Scottish Psalter (1650). This text is most commonly matched with the 1872 tune CRIMOND by Ms. Jessie Seymour Irvine of Scotland, but I really like it with the early American folk tune PISGAH, as recorded, for example, by the William Appling Singers. However, both melodies, I feel, are difficult to sing congregationally.

- “My Shepherd Will Supply My Need” by Isaac Watts, from The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament (1719). This text is traditionally paired with the tune RESIGNATION, first published in the fifth edition of the shape-note hymnal The Beauties of Harmony (Pittsburgh, 1828), compiled by Freeman Lewis, but first appearing with the Watts text in The Valley Harmonist in 1836. My playlist features a performance by the female a cappella quartet Anonymous 4 (the music arranged by Johanna Maria Rose; see video embed below), as well as by folk singer Claire Holley, who recorded the hymn at the request of a friend who told her it was the song that helped her get sober for good. I also like the minor-key setting by Stephen Gordon.

- “The Lord Is My Shepherd (No Want Shall I Know)” by James Montgomery (1822), with music by Thomas Koschat (1862). Here’s the Lower Lights:

- “The King of Love My Shepherd Is” [previously] by Henry Williams Baker (1868). This hymn is most often sung to a traditional Irish tune known as ST. COLUMBA (my playlist features both a choral performance by the Choir of Kings School, Canterbury, and a folksy solo by Luke Spehar) and occasionally to MCKEE, also from Ireland, as recorded by Redeemer Knoxville.

At my church we use Wendell Kimbrough’s musical adaptation of the psalm, “His Love Is My Resting Place.” Do you sing Psalm 23 at your church, and if so, what version?

Probably my favorite choral setting is by Bobby McFerrin, “The 23rd Psalm,” performed below by his VOCAbuLarieS, featuring SLIXS & Friends, live in Gdansk, Poland, at the Solidarity of Arts Festival on August 17, 2013:

Some people are thrown off by McFerrin’s use of feminine pronouns for the Divine in this song. God has no literal sex because God does not possess a body, so our gendered binaries are inadequate—but scripture and church tradition refer to God using masculine pronouns. I’m not bothered by the “She” throughout, or even “Mother,” but the substitution of “Daughter” for “Son” in the Trinitarian doxology at the end is theologically confusing, since Jesus was a man. But I get what McFerrin is doing.

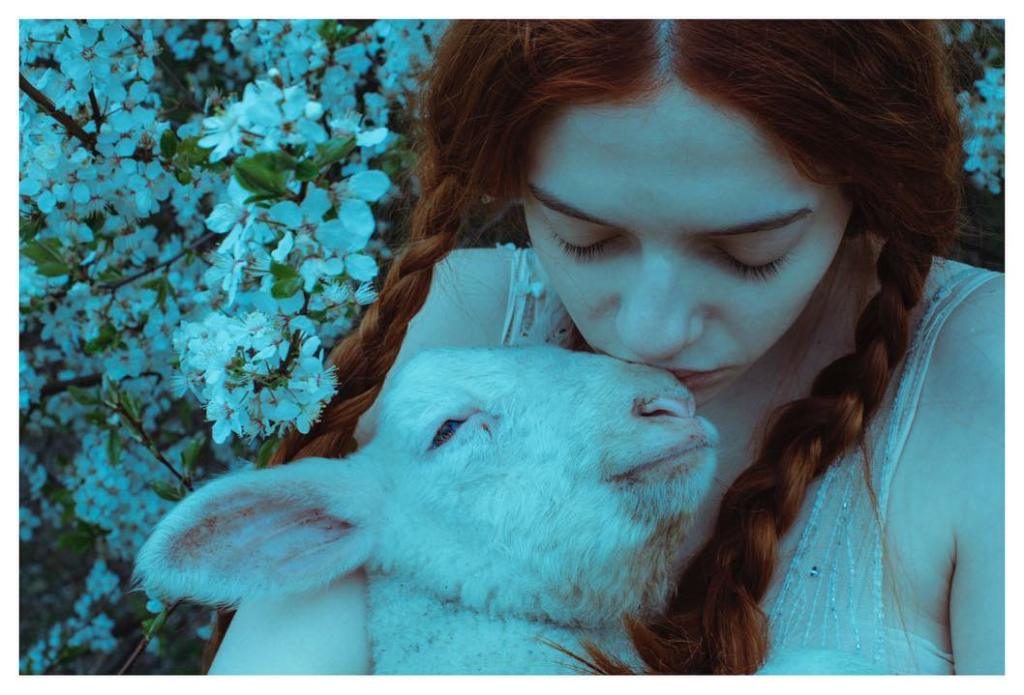

How does the change in gender impact your reception of the psalm text? We’re used to seeing religious imagery of a man with a sheep slung over his shoulders to embody the metaphor of God as shepherd—but what happens when you picture a shepherdess in the role? Note that it was not unusual in the ancient Near East for girls and women to tend their family herds (think of Rachel and Zipporah in the Old Testament, for example), and still today across the globe there are many female shepherds.

McFerrin dedicated his “23rd Psalm” to his mother.

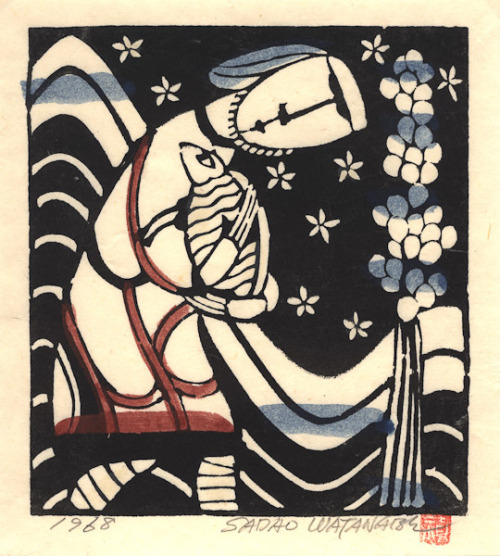

(The above artworks, sourced from Instagram, are from the 2019 series The Shepherd by Laura Makabresku, a fine-art photographer from Poland whose work is influenced by her Catholic faith and by fairy tales.)

Here is a selection of other songs from the playlist:

>> “Adonai Ro’i” is a setting of the original Hebrew of Psalm 23 by Jamie Hilsden of Misqedem, a band from Tel Aviv, Israel, that is heavily influenced by Middle Eastern and North African music styles, often utilizing microtonal scales, irregular time signatures, and regional instruments. The song is sung by Shai Sol. (Available on Bandcamp.)

>> “The Lord Is My Shepherd” by Paul Zach of the United States:

>> “El Señor es mi Pastor” by Omar Salas of the Dominican Republic, a salsa song:

>> “Ke Na Le Modisa” by the Soweto Gospel Choir, sung live at the Nelson Mandela Theatre in Johannesburg in 2008. The song is in Sotho, an official language in South Africa and Lesotho.

>> “The Shadow Can’t Have Me” by Arthur Alligood:

>> “Done Found My Lost Sheep,” an African American spiritual sung by Lucy Simpson [previously] for Smithsonian Folkways, based on Jesus’s parable of the lost sheep (Luke 15:1–7):

>> “Our Psalm 23” by Gabriella Velez, Kevin Dailey, Justin Gray, and JonCarlos Velez of Common Hymnal, featuring Sharon Irving: